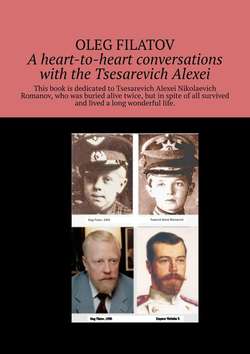

Читать книгу A heart-to-heart conversations with the Tsesarevich Alexei - Олег Филатов - Страница 4

PERSONAL REMINISCENCES BY THE FAMILY OF VASILY FILATOV

REMINISCENCES OF OLEG VASILYEVICH FILATOV

ОглавлениеForced to conceal his true origins, he had to recast his knowledge and upbringing and make himself as unremarkable as possible.

In 1988, as he was dying, my father said: “I have told you the truth, and you must know the pass to which the Bolsheviks have led Russia.” We, his children, are certain that he was not deceiving us. Unfortunately, he told us very little, and we find we still have questions for him. His spirit, though, seems to be with us. And we ask him our questions, and it feels like we are going through time and communing with him. While your parents are still alive, you accept it as your due, not giving any real thought to the fact that they are not immortal. This is why now we have to gather the crumbs of what he said, filling in his story with our own thoughts and the new facts recently uncovered. That is why my father’s story is interspersed with my own thoughts. The inquiries are not over. We have been helped to bear this heavy cross that was placed upon us by our friends, relatives, comrades – in – arms, and scholars who have taken an interest in this story. I hope that as a result we will all learn the truth.

When I began thinking in earnest about how to tell the truth about my father, I spoke with my friends, colleagues, and acquaintances and came to the conclusion that it had to be told the way he himself would talk about it, not as a historical figure out of a distant era but as our contemporary, a man born at the beginning of the century who suffered through all the hardships, trials, famine, and repressions with his people. It is difficult to imagine what it was like for him, realizing who he was, to remain silent for so many years. How much he had to see and endure for the sake of saving himself and his family, his children. We may never find out the whole truth, but obviously that is what we must strive for. “Non progredi extra gredi” – if you are not moving forward, you are moving back.

My father lived a long life. He compensated for his physical disadvantages through his constant effort to achieve harmonious development and knowledge. This gave him the motivation to go on. We children were born when he was already far from young, and he was heartened by this development, sensing new meaning in his life. When grandchildren were born, he finally opened up and told their mother, my wife, Anzhelika Petrovna, about his tragic fate. This was in 1983, five years before his death. Before that he had told us about it allegorically, a certain segment to each of us. Now we are collecting all his stories and our recollections of him in order to arrive at a better understanding of what happened. Some of the memories of members of our family – his children and his wife, Lydia Kuzminichna Filatova (thanks to whom, actually, he survived for so many years) – have already been published in newspaper articles and have been the basis for the special research conducted by scientists that is continuing even now. Unfortunately, there are many gaps in these reminiscences. He was sparing with his stories, and because we were children, we did not ask unnecessary questions but simply believed him. How can you not believe your own father when you see him suffering and realize that his life might have turned out very differently?

I may have to repeat myself in this account, but there is nothing so terrible in that. What is most important is to be honest. This is the basic principle: to tell the truth no matter what it is. Of course, the archives might suggest a great deal, both the closed and the open archives, to which we do not have access due to several circumstances – partly a lack of money and partly the bureaucracy and the fear that lives on in people. But if we don’t read this page, which obliges all of us to prevent a repetition of something similar, we will never find out how the history of our state might have taken shape had there not been a revolution. If we are talking about repentance, then we still have to sort out who committed the murder of the last Russian emperor, Nicholas П, and why to this day none of the country’s leaders and none of the forensic medical experts or attorneys has proposed a standard version of those events of July 1918, or of how the lives of the people who participated in this Ekaterinburg tragedy turned out.

My father told us almost nothing about his parents. When we would ask where the photographs of our grandmothers and grandfathers were, he would reply: “There aren’t any, everything was lost.” There was nothing surprising in that. There had been a civil war and everything burned up and was lost. But when we began questioning him, he would fall silent. All he said about his own father was that he had been a soldier all his life that he went on his final march of sixty kilometers [almost forty miles], drank some cold water from a well, came down with consumption, and died in 1921. About his mother he said that she was a schoolteacher and taught language and music and was shot as a Left Socialist Revolutionary when he was still a boy. He also used to say that he had relatives but he didn’t know them because they abandoned him in Sukhumi when they went abroad during the civil war. When my mother occasionally asked him in a fit of temper, “Here you are saying that we are doing everything wrong, but where are your relatives?” he would shut down, move off, and stop talking. By the way, he could say nothing for long periods of time – go several days or a month without talking. On the other hand, he was sometimes like a child, especially on days when his health was bad. He would just look in silence. He was mulling over something privately, but there was no sadness in his eyes.

In discussing my father s destiny, I have to say that he possessed exceptional abilities and extensive connections. Recalling him, I come to the conclusion that this man was obviously not who he made himself out to be. Officially, he came from the family of a soldier who due to disability became a shoemaker, a man who went to church school as a child, became homeless as a child, and later became a teacher. Today I reconstruct my reminiscences of him from my own childhood and come to the conclusion that this story is not true and that many of his actions were conditioned by his education, sufferings, and illness.

My father had an extremely broad outlook and a thoroughgoing knowledge of life, history, geography, politics, and economics. He knew the traditions of his own country and other states well. He had mastered foreign languages – German, Greek, Old Church Slavonic, Latin, English, and French – although he did not use them actively. He explained his knowledge of languages and his excel1 lent motor and visual memory by saying that he had always striven to be a harmoniously developed person. He used to tell us: “You are as many times a man as the number of languages you know.” He meant that if you know the language, culture, traditions, and customs of a people who live in some other world, you expand your own possibilities. He read with amazing speed and in great quantities, remembering what he had read very easily. You got the impression that he was extracting information like an automaton. He could recite from memory the poetry of Fet, Pushkin, Lermontov, Tyutchev, Esenin, Chekhov, Kuprin, Heinrich Heine, and Goethe in German. He loved Goethe’s Faust. He explained this by saying that in their family they used to gather in the evenings and read aloud to one another: plays, poems, novellas, and novels in Russian and foreign languages. In this way, the family bonded, relaxed, and conversed.

My father had a great enthusiasm for history, especially military history, and knew it thoroughly, including the troop dislocations and the alignments of forces in specific battles. In demonstrating his knowledgeability in these matters, my father seemed to include himself in the military caste. All his life he used to say: “We Filatov`s have always stood on guard for the state.” When I watched films about the Great Patriotic War [World War II], I often had questions – for example, why at the beginning of the war our troops retreated. My father would answer my question very thoroughly, both about the beginning of the war in 1939 and about the initial testing of the Russians’ strength during the invasion of Poland by Soviet troops. He would explain to me what caused the difficulties with our armaments in the first days of the war. Despite the fact that he, as an invalid, was released from serving in the army, he cited amazingly detailed examples.

For example, he used to talk about how during the Second World War we had to take Rostov twice because the Germans left a barrel of alcohol there – not a barrel really, but a cistern. The Russian soldiers got thoroughly drunk, and the Germans retook Rostov back. So we had to take it a second time. But when the Germans attacked initially, the Russians used electric fences for the first time. They placed them on the banks of the Don and dug them into the sand. It was dreadfully hot, and the Germans were thirsty. When they crawled toward the river, the circuit was completed, and they stayed right there. I don’t know where he got this kind of information.

He used to tell us a great deal about the Russian tsars who built the state and as an example often cited Ivan III, the assembler and organizer of the Russian land, who gave the Russian people the chance to free themselves from the Mongol horde and get on their feet. He recommended that we read, by Ivanov; to get to know Russia’s history better. When he used to talk about the civil war, he would also mention the move the tsar’s family made from Tobolsk to Tyumen. He used to say that a brigade arrived under the command of the Cossack captain Gamin, or Gatin (unfortunately, I don’t remember precisely), for their rescue. He told us how well White intelligence functioned, especially on the railroads. The family had already been warned, men were ready, and it was just a matter of exploiting the situation at the proper time, but in Tyumen the guard was replaced, and the plan failed. Unfortunately, events followed a different scenario, although everything had been made ready to free them.

His artistic qualities were also outstanding. After they already had us, he and mama would perform in amateur shows, and he was invited to transfer to join a professional theater. What astonishes

me most of all is where a former homeless child learned to play keyboard instruments. To this question of mine he would reply in the orphanage in Kaluga – moreover he not only played the harpsichord, piano, and organ, but also knew how to tune them. He loved the balalaika, and although he did not play the guitar he told me that the piano and guitar have identical pitch. He played the concertina, bayan, and accordion and taught them to us. His favorite artists were Shchepkin, Okhlopkov, Chaliapin, Sobinov, and Caruso. He used to say that his mother played the piano, usually Chopin or Beethoven. He himself liked to listen to Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky, and Rimsky – Korsakov. He taught us to sing without tensing the vocal cords, but achieving a smooth tone without strain. His manner of singing was quiet and calm, but very expressive. He sang ballads, operatic arias, and long Russian folk songs and knew an enormous number of chastushki [humorous folk ditties]. I would assist father with endless alterations of the house. At leisure we would play chess. It was a great pleasure to him. He was an excellent chess-player despite his old age, knew by heart a lot of openings. He went on solving chess problems. He had related textbooks, journals. He kept analyzing the games of all the famous chess-players —Alekhin, Eive, Kapablanka, Chigorin, Botvinnik, Spasskiy, Tal’, Cheburdanidze, Karpov. Father knew also the local chess-players, especially in Orenburg. He taught his children how to arrange a defence – Cicilian, Indian, etc. He would always record in pencil the games on sheets of paper or put down important moves on a press-cutting with a chess-board. He called chess the game of tsars. Chess was his passion. He began teaching us various chess openings at the age of three.

Father had a collection of journals with analyses of the international chess championships. When I asked him about some chess-player, he would answer in detail, tell his biography, how he started playing chess, what he became famous for, and at which championships he headed the list. He spoke especially warmly of Alekhin, who was an excellent chess player and played 265 games blind – folded and won. My father used to demonstrate this method of play for us, but he said it was harmful because it sapped so much energy. He himself played chess when he was laid low by pain. He said that he played instead of taking medicine. It distracted you and made you forget about the pain. He subscribed to chess magazines, analyzing and taking notes. He would tell that Alekhin drank and when it was necessary to take part in the world championships, he would stop drinking, go to the mountains, buy a cow or a she-goat, and drink milk to recover his strength. It was when he lived in Switzerland. Analyzing the games of recent world championships, father arranged the pieces as they had been arranged at the beginning of the game, for instance between Tal’ and Botvinnik. Starting to move the pieces, he would say: “Well, Botvinnik moved the bishop from G1 to F3. Let’s see what Tal’ will do. Tal’ moved a pawn let.” And all this information, the manner in which it was told and the conclusions, how one ought to have moved and what was the result, and where this or that chess-player had made a mistake, – everything settled in our minds. Father did so for us to acquire a passion for this game. It helped him live, his whole life he used to play with an imaginary partner.

He collected hooks and gear for fishing, ah kinds of screws and nuts. He had fitted out several boxes for this, in each of which he kept something. We used to laugh at this weakness of his, but whenever we needed something, we would immediately go to him and he would locate what we needed.

My father loved photography and started teaching it to us when we were children. He bought us “Smena – 8” cameras and books for amateur photographers. When there was time, we did photography from morning till night. Lessons with my father were very interesting for us. My parents provided everything we needed for all this. And he would talk about his own childhood a little. He said that he had liked to play cops and robbers. That was a fashionable game at the time. He used to tell us that he was very mischievous and never gave the adults a moment s peace. For instance, once at a lesson in divine law he played a joke on the priest, nailing his boots down. He was punished for that.

Two of us, his children, are absolute blonds, and two are dark. He was quite dark, too, but he said that as a child he had fair, curly hair. “Every – one loved me. They called me fluff and cut my hair very simply, bowl fashion. It was later that life changed me.” His hair was jet black and only beginning to show gray just before his death.

He often used to say that one needed to know how to speak well and cogently and how to declaim. It is interesting that as an example of eloquence he cited not only Horace and Socrates but Trotsky as well. He used to tell us that during the civil war, when the Red Army units were retreating, Trotsky could talk for hours. The soldiers who heard his speech would attack the enemy and fight to the death. He used to tell us that a person must know how to do that, inasmuch as God has given him the ability to speak. You must construct sentences and set forth your ideas correctly. Each word must be substantive and in no way ostentatious.

He dreamed that I would become a lawyer. When I would ask him why he wanted that so much, he would reply: “Well, why, then you could sort matters out. You would know what to do.” He also made me study foreign languages. I would ask him why he did not speak to me in German, which he knew well, or teach it. He replied that this language had grown hateful to him ever since the war with the Germans.

In childhood, I had no trouble remembering all this. There is no barrier, nothing to fear, especially when it is your parents teaching you. I never felt fear when I was with my father. I felt as though I was living in clover with him. He was an exemplary family man, spending a lot of time with his children and teaching us nearly everything. For example, to write with our left hand in order to develop both hemispheres of the brain. He said that the nobleman could fence with both hands and switch his sword from his injured arm to his healthy one. He made embroidery stand himself and made me learn how to embroider on it – cross stitch, satin stitch, and other ways. When I would ask him why I needed this, he would reply: “What do you mean? This is simply something one must know how to do.” Then he would check my work when I embroidered handkerchiefs for Mama and my sisters for their birthdays. He taught us how to draw. First how to hold the pencil, then how to draw with it, and then he gave us colored pencils. He showed us how to draw on a grid in order to observe symmetry and, later, from memory. Only after that did we move on to watercolors, and later to oils. My father wanted me to show my work in art contests, so I did. He did sculpture with us – using plasticine and clay. He taught us to write compositions, selecting the material we needed from books, examining pages along the diagonal, and selecting what we needed to develop our theme. So that we would know how to express our thoughts figuratively, he would have us write, for example, how the birds fly in spring. He himself made starling houses and taught us to love and study nature. Generally speaking, he loved the spring and always became despondent when autumn arrived. We did not have a church in our settlement, so his soul refreshed itself in nature. By the way, he was very knowledgeable about medicinal herbs.

He did not try to impose his knowledge and abilities on us. A flock of birds or geese would fly overhead and he would suddenly ask, “How many?” If you saw it once, you had to remember it instantly – that was his system of childrearing. I was supposed to remember after one time the names of streets, buildings, people, transportation, and even which way the wind was blowing when they took me to Orenburg. Leaving an unfamiliar building, I was supposed to describe to him what objects were there and how they were laid out. He himself was very observant. When you walked with him in a crowd, he would say, “Did you see that man who passed? He has a peculiar gait. Do you see this one? He keeps looking around, searching for something.” He noticed all kinds of insignificant details and made me remember everything.

Now it seems unusual to me that from my very childhood, somewhere around nine years old, he taught me to remember everything he said the first time. He used to say, “Remember what I say the first time because it not going to repeat it for you. You have to know this in order not to repeat mistakes and not to tell anyone, or there will be trouble.” Even then I realized that he was concerned not only for us but for other people as well. He used to tell us about them and show us their photographs, saying: “I`m showing you one time. I`m not going to show you again. Remember these people.” But whether or not they were alive at the time, we didn’t know.

Sometimes certain people from some unspecified place would pay him very brief visits. He would go out with them and discuss something with them. We never saw them before or after. We could not get him to tell us who they were or why they had come. He smiled and said nothing. Probably he didn’t want us to know his former life and didn’t want us to expose ourselves or those people to danger. In. the 1960s, my father would write postcards to someone and give them to my younger sisters, who could not read yet, to drop in the mailbox. If we asked him whom the postcards were for and what was written there, he only smiled and said nothing.

He had amazing friends. For example, there was the old man Yavorsky, who lived in our village. Once my father took me along to see him, when I was about nine. There was an old man wearing a belted white peasant shirt lying on the stove. My father suddenly said to him: “Tell me, grandpa, how did Nikolai Ivanovich Kuznetsov die?” The old man raised up onto one elbow and looked at me: “And who’s this with you?” “This is my son; you can talk in front of him.” And then the old man told us about waiting for Kuznetsov with Strutinsky. That was their assignment. He was in the Signal Corps in Poland. They were waiting for him outside Lvov, but he never did come. Then they received the news that Nikolai Ivanovich Kuznetsov had died – he had blown himself up when he fell wounded into the hands of the nationalists. For me what was most interesting is where my father met him. He himself said it was at Uralmash [Urals Machine – Building Factory], where he had been trying to get a job.

Often in our childhood years we would see how lonely he was, despite the fact that he had a wife, our mama, who slaved away indefatigably to raise us. All those years, especially in the 1960s, he spent a lot of time at his radio, listening to “The Latest News” from morning till night. This is when he began telling me about the revolution, politics, and Chamberlain. He was constantly thinking about Kerensky. He knew not only who Kerensky was but for some reason how he had fled and where he lived. He said that Kerensky made himself out to be a leader but in fact was an adventurist. My father would keep returning to the idea that tsars worried constantly about the state, the treasury, and the army, without which there was no state, and watched over their Orthodox Church. He told us how they killed Trotsky in Latin America.

My father was an invalid. (He used to say: “I was born a cripple like this.”) His left foot was withered, size 40, and his right a size 42. Once he said that his foot did not wither until about 1940. He had a curvature of the spine, many scars on his back and arms, and the traces of shrapnel wounds at his waist, under his left shoulder blade, and on his left heel. This evoked puzzled questions from us. The man had never been in a war, but he was so crippled. Where? When? But it was not done to talk about this in our family. Once as a child I saw his wounded back and asked him what had happened. “Well,” he said, “there was a certain business. They were shooting in a basement, killing people.” When I asked him what happened to his foot, he waved his hand and said that if they had cut off his other foot he would have been totally incapable of work. “But this way I can work and earn my living.” His foot always hurt, he had cut himself with a razor somehow on the heel, and he had a terrible scar there. He went especially to Leningrad to buy “general’s boots,” which had a high instep and were sometimes sold in the 1960s. He said that previously he had had an orthopedic insert; they had given him massages, stretched and massaged his foot. He had wanted to have an operation, but he was afraid his heart couldn’t take it, even though he was relatively young.

It must be said that he never went to doctors and no certificates of his illness remain. Only once, in 1975, we made him go for a physical. This is the only information we have about the state of his health. By the way, we have never had photographs of my father in his younger years. There are a few from before the war, and those there were had been taken much later. Generally speaking, we have very few documents for him, although he taught us to store every document and every paper carefully and never lose anything. He would tell us that his birth certificate had been lost and so he had had to reconstruct it from the church’s registers. “So it was a dentist who established my age. But he was wrong.” My mother remembers that he confessed to her in 1952 that he was forty eight.

Despite his disability, he possessed stunning endurance. He could go great distances without a stick, favoring first one leg and then the other. He made these treks daily, especially in the summer on his days off, when he walked a couple of miles to the river to fish. He was very strong spiritually and carried himself with the greatest dignity. I don’t remember an instance when he was humiliated by anyone or called an invalid. He himself simply came undone whenever his illness kept him from doing something. This would get discussed and then he would calm down. All his life he did certain special calisthenics and said that without them he would be as skinny as a rail.

Often he would suddenly fall ill. We couldn’t figure out what was wrong, but he never went to doctors. He would put himself to bed and lie there for hours on end. He swallowed certain tablets and was always taking ascorbic acid. When I would ask him what was wrong with him, he would answer: “I got this from my parents. And I was left a cripple my whole life. People said my parents should not have married, but they did and gave birth to me the way I am.” When he was in pain from being hit by something in the foot, he would bandage up the bruise and put himself to bed or sit hunched over, muttering something nonstop. Once I heard him repeating the Our Father. This was his defense. He used to say: “There couldn’t be anything more terrible in life. The most terrible thing of all is theIpatievcellar.” Of course, these phrases sank into our minds.

Usually he got up early, did his calisthenics, splashed himself with cold water, and always shaved very carefully. This amazed me and I would ask, “Papa, what are you, a soldier?” He would answer: “No, but my ancestors were all soldiers.” He was painstaking and neat about his apparel, and if he was going anywhere, then the packing was an entire process. He went off to work with dignity, and we saw that this was his principal business. After I was 16, he began having me lift weights and dumbbells. In the summer I loved to swim and did this very well. He told us it was easiest of all to swim on your back or do the butterfly, if you didn’t make noise.

It was pure pleasure to see him wield an ax when he was chopping wood. We thought it took half a lifetime to learn how to do that so well. He taught us how to chop wood, too, so we wouldn’t injure ourselves. He told us how Russian warriors knew how to defend themselves with an ax, switching it from hand to hand. He even tried to teach us how to throw an ax. At school there was a military office where they kept small – gauge rifles. He taught us how to shoot with them: how to hold the butt and press it to your cheek, how to lower the trigger while you hold your breath, and how to aim.

He had a reasonable attitude toward food. He loved fish, cocoa, wine, and champagne. I remember, when we were children, sitting down at the table and each of us being given a starched napkin. There was a soup tureen on the table and everything was very formal. We were not allowed to pick up our spoon first. For that you could get a smack on the forehead. When he taught us to sit at the table and use a fork and knife, and what the table setting should be, my mother would say: “There you are again with your silly White Guard ways. I just hope to God no one finds out.” When we got older, all this came to an end. The china disappeared, and we started eating like everyone else. Any information was passed on to us before a specific age. Evidently, he felt that this ability [to be well mannered] no longer had any application.

I think that he knew and experienced enough to fill several books and films. He used to say that all you had to do was read My Universities and Journey among the People by Maxim Gorky to know what his youth had been like. When I read How the Steel Was Tempered, I asked, “Papa, was it you who was Nikolai Ostrovsky?” He smiled and answered, “No, I wasn’t Nikolai Ostrovsky. Anyway I had a worse fate than he did.” My father often told us how he traveled around in his childhood. As an example he cited Mark Twain’s book about Tom Sawyer, and he liked Jack London, too. He watched films about the war and intelligence agents very attentively. He noticed what demeanor one needed to have and how one needed to educate oneself to say nothing extra. He liked certain sayings: “My tongue is my enemy” and “We were given a tongue to hide our thoughts.” I don’t know where he got this kind of information, but he would tell us that the Germans had a spy school where they studied Orthodoxy and divine law. Then they were dropped into Russia. According to him, these people were caught once at the railroad station in Tyumen when they tried to poison the food and sprinkle poison in the milk cans.

We lived in a German – Dutch settlement founded during the days of Catherine II in the Novosergievsky District of Orenburg Province. The settlement had an unusual name: Pretoria. It was either Holland or Germany in miniature – with its windmills, cheese factory, and particular way of life. The houses were made out of huge boulders, the large roofs and doors out of thick wood. If you pulled on a rope, half of the door would open – the carved, wooden half. And everything was always left unlocked. No one ever stole anything. It was tidy. My father worked there as a geography teacher at the high school and was always highly regarded. His pupils loved and respected him. Many people knew him in the town and the province as well. He was a sociable man and was also involved in civic activities – he was a deputy.

He was always comfortable with people of other nationalities. He never taught us to treat them in any special way. He said that one had to study another person’s experience in order to learn how to live better. He called upon us to be tolerant. He did not recognize Baptists or sectarians. In his understanding, they created a superfluous background, not being a major spiritual movement in religion like Orthodoxy. He remembered prayers and created them for himself. He said that by age fourteen he knew them all by heart.

Our family’s life was spent in villages removed from large cities and communications, so our only connection with the world was the radio, and later, in the 1960s, the television.

Holidays had a special significance for the family, because they bonded the family, creating warmth, coziness, and a special mood. We children always looked forward to them, especially New Year’s, birthdays, and so on. The New Year always had special meaning for our family. Mama and Papa tried to make us part of the general preparations not only at school, where they were always the leaders, taking part in the amateur theatrics. Mama organized carnivals, sewed costumes, embroidering them with beads by herself and with our help.

Father read by heart: poetry, Koltsov; Lermontov, Pushkin; Krylov’s fables. And he liked reciting the works of Anton Chekhov, like “Boots”, “The Boor,” “The Horsy Name, “Lady with the Lapdog,” “Nasty Boy,” and “Surveyor,” and Kuprin’s “The Duel.”

Mama sang love songs, accompanying herself on the guitar. At home, we put on plays, learning the roles for the fairy tale “Kolobok,” “The Tale of the Golden Fish,” “Filipka, “Tom Thumb,” “Speckled Hen,” “Nasty Boy, and so on.

The school in the village of Pretoria was a wooden structure dating to 1905, with a large assembly hall, where we would put a 30 – foot tree and the teachers would gather around it with their children. Children of various ages waltzed with their parents. I always wore a large bow tie and I liked to dance. Father liked to dance, but only the slow tango. We had a teachers’ choir, in which my parents sang. The director was Turnov Alexander Alexandrovich, the music teacher.

At home, my parents also set up a tree, which we kept up for two weeks starting December 30. My parents and sisters and I made toys from paper, ships, crackers, we glued and drew pictures, we liked to illustrate scenes about the boy from “Snow Queen,” how he suffered and searched for his sister. We also had glass ornaments for the tree. We set the tree on a crisscross stand or in a box with sand. Papa helped us embroider kerchiefs with themes from nature or from stories like “Kolobok” and “Inchman,” the little man who lived in a music box.

Mama and Papa put presents under the pillows on birthdays, but for New Year’s they would dress up as the Snow Maiden and Grandfather Frost, take our presents out from under the tree and congratulate us, and we would give them our gifts, sing a song about the tree, and dance around it.

Papa often recalled how he celebrated New Year’s as a child. “But back then,” he said, “It was different. We also had Christmas, and that was a big family holiday.” We would ask, “What was that holiday and why don’t we have it now?” He would reply evasively and say that it was hard to talk about it now. We did not have a church in the village, but he would mark the occasion by recalling his life and talking about the “old” New Year’s, because after the Revolution all the dates were changed and people went to church then, but we lived in a German – Dutch village and the locals had their own holiday, which father did not recognize and said that it was a holiday based on a different calendar.

At New Year’s some residents went to Baptist prayer houses; some dressed up and visited friends.

My father’s birthday was around that period, and he always said that the certificate he was given in the 1930s indicated that he was born December 22, 1908, but he counted and figured that in the new style [the Gregorian Calendar] it was January 4; but he told Mother that it was January 28, and she asked him, “So which is your birthday?” and he would say that it was all mixed up.

We never had guests for his birthday. We celebrated it in the family He recalled his parents, who died early in life. We wrote him cards, made

drawings, gave him books on chess, fishing, hunting, and history, and embroidered hankies for him. Unfortunately, because we moved often, it was all lost, even though Mama often exhibited her work at school, where she ran the sewing club, and in regional shows, as were our drawings, especially the ones I did with Father, for the holidays. I don’t know what could be found of that now. In connection with Christmas Father often talked about “Christ’s egg” and the suffering of Christ at the hands of bad people. He told us about how the first holiday trees appeared in Russia, about how the holidays were celebrated by the Slavs in ancient pagan times and later, starting with the Russian tsars until Peter the Great, and how he traveled around Russia, a “wandering beggar,” and said that he had to keep in his memory everything that happened to him. And he told us that the Russian tsars loved to hunt in those days. He told us that there was a fast before Christmas, that people prepared themselves for the feast day, and that he used to be like that, he observed Advent, but now few people remember it.

On holidays Kagor wine was served, which my father always called “church wine.” Mama made pies filled with cabbage and with berries, jellied fish, and roast goose or suckling pig. (Father often told us that as a child he and his father “at night” cooked goose “African style,” cooking it without removing the feathers, in day in a bonfire, and that the feathers came off when you removed the day. They also cooked pheasant and quail that way.) Our family loved desserts, we children had cakes, and our parents drank champagne.

We children spent the holidays outside, making snowmen, playing with snowballs, building fortresses out of snow. I spent my whole childhood far from cities, and came to know large cities only later.

In school we studied the history of Russia and the history of the Party. Everyone knows what kind of sciences these were. For him, history was a favorite subject, the basis of his children`s upbringing. He believed that all the misfortunes in Russia were due to a lack of upbringing and education, that this was the greatest of shortcomings and led to misunderstandings, incomprehension, and a reluctance to penetrate to the essence of events, and, in the final analysis, to wars. He used to say that to know history we must read not only textbooks but other books as well. For example, we needed to read about Emelian Pugachev, Suvorov, Catherine II, and Peter I and know much more about them than we got in school. We would ask him whether he knew the history of his own family. And he would tell us how his people grew up on the river Uvod in Kostroma, where his ancestors lived in wooden huts and hunted and fished. “They always hunted with dogs. You must never beat dogs. If, God forbid, anything happened and you offended it, it could betray you during a hunt.” He told us about some distant ancestor of his who went hunting for bear in the winter, but his dogs abandoned him in the forest because he had beaten one of them. The bear was full, of course, and only laid the hunter low with a fallen branch. When the hunter came to, he shot the dogs. “But,” he said, “my people also went after bears without guns. They made an iron ball with spikes and threw it at the bear. He caught it with his paws and the spikes cut into them. Then they had to ride up to him and slit open his belly. That was their idea of entertainment.” (My father was a marvelous marksman and loved to hunt. He used to say that in the old days he had had a dog, a rust – colored Russian hound.) He used to say that all his ancestors were very blond and very fair – haired. “And our name,” he said, “came from Filaret. Once there was a man named Filaret, and we are descended from him.” Today I understand why he said this. “Filaret” comes from the Greek, filat. Later, when we were attempting to sort out his allegories, we asked, “So does that mean that you are the boy who was rescued during the execution of the Romanov family?” And he answered: “Of course not, I descend from Filaret.”

I learned from my father about the execution of the tsar’s family for the first time in about the seventh grade, when we began going through the history of the Revolution. That was when I first heard the name of Yurovsky, who, as my father said, organized the entire affair. I could not understand how the boy could have lived (in his stories, he spoke about the tsarevich only in the third person and called him “the boy”). He used to say that this boy saw the entire crime and what happened afterward and that they hunted for him all the rest of his life. I asked him, “So where did he hide?” And he said: “Under a bridge. There was a bridge there at the crossing, and he crawled in there when the truck shook.” “But how do you know this?” He fell silent. “My uncles told me.” “But who are these uncles?” “Uncle Sasha Strekotin and Uncle Andrei Strekotin, who were in the house guard. After the front, they were stationed there. Oh, and also Uncle Misha.”

(According to the reminiscences of our father, it was during this reloading that Alexei hid under the bridge near the railroad, and, after the truck left, moved along the right-of-way, reaching Shartash Station by dawn. But in Ekaterinburg was more than one bridge near crossing number 184 where the truck could have become stuck in the mud and required unloading.

From the Ipatiev house, two routes led through, or past, the Upper Isetsk works to the Koptyaki road. The first went over the dam at the town pond, a guarded site where a truck on a secret mission would not have wanted to go. But a block downstream on the Iset River, which turned into a brook right below the dam, was a small bridge and next to that, the machine shop rail branch, which led to the Rezhevsky plant. It was about two-and-a-half miles from here to the Shartash Station. Alexei could have covered this distance in two hours in the dark. The search party did not go in that direction and could not have found him.

The other route went from the Ipatiev house on Ascension Avenue to North Street, left over the bridge across another brook, past the new and old stations, past the Upper Isetsk plant, and out onto the Koptyaki road. The truck could have become stuck at this bridge, too. Once again, alongside it was the railroad right-of-way, which continued for about three miles to Shartash Station. Alexei could have covered this distance in two hours as well.

According to the reminiscences of father, on the morning of July 17, the Strekotin “uncles” found Alexei at Shartash Station, and drove him 140 miles to Shadrinsk. The road to Shadrinsk – the terminus of what was at the time a blind branch of the Ekaterinburg-Sinarskaya-Shadrinsk line – was still open. Voitsekhovsky and Gaida’s shock troops were moving toward Ekaterinburg from Chelyabinsk in the south and from Kuzino Station in the west. Easterly directions – toward Tyumen and Shadrinsk – were still open during the week of July 17—24. Alexei reached Shadrinsk with an escort during that week).

He also used to tell me how the bodies of the executed were thrown into tiny mine shafts. “If you want to see how it all was, go watch the movie The Young Guard. There you’ll see large mine shafts, like in Alapaevsk, but you’ll have a notion of those events.” To my question of why I would care about that, he replied: “Why do you need a reason? You’ll know history.” I went to those movies and all my life I remembered the mine shafts the people were thrown down in the film. About the grave he said that he remembered the place, where it was. And that there were no traces left.

It was not until later that I began asking myself how this could be, if this were a boy, a chance witness of a certain episode, he could easily have lost control and cried out or given himself away somehow. In order really to know everything from the beginning (Tobolsk and the Ipatiev house) to the end (the burial site), he had to have passed through the entire chain of events. Could there have been several boys? All of them would have had to have a diseased left foot. How many such boys with a sick foot (specifically a left foot) could end up in the same place at the same time so that one of them saw the execution, another the road along which the bodies were transported, and so on. Which means there was one boy? In addition, there was nowhere to read about the details he told us at that time. This was not publicized or popularized in the official press, and there was no such thing as reading something on the topic in the library, which is why this stuck in my memory especially. He used to talk about these events when the conversation turned to tsars and history, and this was embedded in our memory. My father did not often return to these stories (it would drive anyone crazy to talk about this all the time). He raised us very competently and sensibly, stage by stage, step by step. He spoke about what had happened to him cautiously, so that his story would stay in our memory like little specks. He did not tell us very much about the Revolution. He did say that they broke up and smashed everything, murdered people, and destroyed everything the Russian people had created, because they had lost their faith in God.

My father used to say that the Strekotins were very fond of this boy. They used to talk to him through the fence and exchanged handkerchiefs and other small objects with him. They came from working – class families – ordinary Red Army soldiers from the Orenburg front. One of the Strekotins, Andrei, perished on the Iset River during Bliukher and Kashirin’s retreat to Perm on July 18, 1918. As my father said, Uncle Sasha Strekotin used to tell the story of how on that day Andrei had had a premonition and had said: “Melancholy is swallowing me up. They’ll kill me today, Sasha.” And no sooner had they said goodbye to one another than that is what happened. He raised his head too high out of the trench and a stray bullet struck him right in the forehead. I would ask my father how the Strekotins vich. According to him, they fled with Bliukher into the forest, where everyone forgot about them.

Under the command of the famous civil war hero Kashirin, the brigade left Ekaterinburg on July 18, 1918, and got as far as Perm. On August 12, 1918, Bliukher had joined up with Kashirin and was his second in command. I often wonder about another coincidence: in our village there were some Kashirins who looked after us in our childhood. For the most part their family lived in the next village, but they would come to see my father and help him out. In talking about the Strekotins’ participation in rescuing the tsarevich, my father made it very clear that they were aided by tsarist intelligence. And indeed, as of April 1918, the Academy of the General Staff had been transferred to Ekaterinburg. Many of the officers who studied there had already been through the war and, naturally, regardless of whether the boy was called Alexei Romanov or Vasily Filatov, there was no need to prove anything to them because they simply knew him by face. According to my father, in Ekaterinburg information was exchanged with the help of semaphores, which were done from the attic using a candle, which they turned “on” and “off” with their hand. By the way, my father taught us Morse code. He said that the most important thing in this alphabet, as in music and semaphore, was the concept of the pause, and that Morse code had been widely introduced in Russia and the tsar’s ships had started using it. He did not tell us about the people he communicated with in this way, but he did show us several photographs. I remember he always loved films about secret agents, and when we watched them with him, he always drew our attention to their knowledge and restraint, which was essential to possess in order not to say an unnecessary word.

The further story of the rescue is this. With the help of several workers, Mikhail Pavlovich Gladkikh (Uncle Misha) took the “boy” to Shartash Station and from there to Shadrinsk. They brought him to the Filatov family, who laid him down next to their ailing son Vasily, who was approximately the same age as the “boy.” After a while Vasily died of fever or, as they said at the time, the Spanish flu. Thus my father became Vasily Filatov. They established his age by looking at his teeth, and later they found a birth certificate, and everything fell into place and matched up quite logically. Thus, in 1933, at the Road Building Workers’ School where he was studying, he was asked whether he had been deprived of his voting rights. In the reply it says he hadn’t and was the son of a shoemaker. [If one was considered a White, or a member of the bourgeois classes, the Soviets would revoke his or her right to vote.] For a man with this kind of legend, everything had to match up. Of course, the people who helped save him and who worked out the legend by which he lived his life had to have been relatively well educated.

At the time [of the rescue], Shadrinsk was an important center in Perm Province. They treated many wounded in these places, taking advantage of the local medicinal springs. My father used to say that he was rendered his first medical assistance at Shartash Station. After he was given his new name, they took him to Surgut, where they treated him for loss of blood. Naturally, this could be done only by people who knew in detail both his illness and the methods for treating it, considering the local natural conditions. After all, the boy was very sick. These people had to have known beforehand where to take him, where they would be able to help him using traditional and folk medicine and to provide him with a devoted and experienced physician. In those regions there were many folk healers, and my father put great faith in them. I remember when we were living in the Urals he would travel to the next settlement of Kichkas to a healer and study with her. She taught him to gather broken human bones. She would smash a clay pot, sprinkle the broken pieces into a sack, and make the person gather them by touch. At the river, my father searched for clay for mud baths and treated himself. The healer helped him do this. AH his life, my father was good at identifying herbs and used them for his treatment. He used to tell us that he had learned this from northern peoples, when he was living in Surgut. The Khanty-Mansy and Nenets tribes had taught him this. It is a wellknown fact that they have methods for stanching blood, as they are constantly battling scurvy.

With the assistance of Archpriest Golovkin, we are able to obtain from the Russian State Archives a copy of the autobiography of Vladimir Nikolaevich Derevenko, the tsar’s family physician. We know from Derevenko’s autobiography and work by contemporary researchers that shortly before the execution; a General Ivan Ivanovich Sidorov arrived from Odessa to contact the tsar’s family (evidently an emissary from Nicholas II’s mother, Marie Feodorovna Romanova). He made contact with Derevenko, who was also in Ekaterinburg at that time but living not in the Ipatiev house, together with everyone else, but separately, at liberty, and he was allowed to visit the tsar’s family regularly to examine the tsarevich. In Nikolai Ros’s book The Death of the Tsar’s Family, which was published in Frankfurt in 1987, I read that in one instance Nicholas II asked Dr. Derevenko to take out of the Ipatiev house the most precious thing they had, Rasputin’s letters, and that Derevenko managed to get them past the guard. I think that this can serve as confirmation that it was he, a man devoted to the tsar’s family to the end, as well as a physician intimately familiar with the boy’s ailments and the means for helping him, who was involved in his rescue.