Читать книгу Solar Wind. Book one - Олег Красин - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

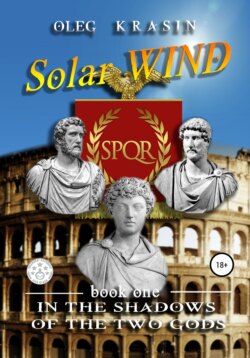

Book I

Dog philosophy

ОглавлениеThe villa of his parents, where Marcus lived, was located on Caelius near Regin's house. It was one of the seven hills of the city, which had long been favored by the Roman nobility. The area became fashionable among patricians because of the picturesque and sparsely populated area. There was no crowding nor the crowds of the big city, here they did not hear the noise and cries of the crowd, nor the disgusting smells of Roman streets.

From the height of the hill, Marcus had more than once seen the splendor of the world capital, seeing the giant Flavius Amphitheatre, the beginning of the forum resting on the Capitol, the new thermae of Trajan. The view of Rome, mighty, beautiful, irresistibly stretching upwards, as a living organism grows—conquering the peaks and forever crashing into his memory. He would remember many times his Caelius, mighty oaks crowding on the slopes, air full of the bloom of spring and youth, warm sun overhead.

Marcus’s great-grandfather Regin told him that one of the famous Roman generals, the winner of Hannibal Scipio Africanus with his cohorts, stayed on Caelian Hill. Here he marched triumphant, proud of his victories in the glory of Rome, dragged after the carts with gold and prisoners of the captured lands. Great-grandfather tried to instill in Marcus a deep pride for Rome, and what best makes one proud than the victory of ancestors?

Oh, this hill of Caelian Marcus would always remember.

Much connected him to this hill. Here, in his parents' villa, he grew up under the care of his mother. Father, Annius Verus, after whom Marcus took his name, died early, and he remembered him vaguely. Actually, there were only two fragments of memories remaining; the father in iron armor and purple cloak beside his mother, holding her hand, and the second…

Father walks in the garden near the villa. He's in a white toga. It is early morning and sunlight, like a waterfall flowing from a clear blue sky, completely fills the garden. From the humid ground slowly rises the milky mist, absorbing brown trunks, green branches, leaves and gradually concealing the father. His white toga merges with white smoke, as if the figure of Marcus Annius Verus is removed deep into the garden. Marcus seems to see that he sees a colorful picture, which is filled with milk. It is as if the spirits of the garden seek to hide his father to spite him. The fog is stronger and higher. He sees his father’s waist, his chest, and his head, but then he completely disappears behind a dense shroud …

However, Marcus felt implicit gratitude to his parents for his masculinity, for the fact that he loved his mother, did not offend her. Perhaps that is why she did not marry, although the women of her circle, remaining widows, did not remain faithful to the dead for long. And some divorced their living husbands, remarrying three or four times. Such actions in Rome were not condemned, but rather were usual.

Here on the Caelian Hill, as his great-grandfather did not recognize the benefits of public school, Marcus's homeschooling began.

Music was taught to him by the Greek Citharode20 Andron, with whom Marcus also learned geometry. Musician-geometer, what could have been weirder? But amazing people often met a curious boy. Or maybe he saw the unusual in the fact that the others considered the matter ordinary?

And Marcus studied painting from another strange man, also a Greek, Diognetus.

“Keep your hand softer, don't strain the brush!” Marcus was taught. “Art is like nature, vague strokes replace clear lines, empty space filled with inner air. This is where the mystery is born. Look at the sculptures covered with toga, tables or cloaks. Behind the soft folds is human flesh, the living soul, though wrapped in marble. This secret of revival is incomprehensible and eternal, but we Greeks still prefer the naked body, with the beauty of which nothing can be compared.”

“Didn't the poet Lucian condemn the call?” Marcus, who studied Lucian's grammar satire, asked.

“Nudity does not hide anything, and this is its appeal,” Diognetus concluded.

Marcus looked at the Greek mentor, absorbed, listened, watched. Diognetus taught him a lot. He was not like the grammar teachers of Alexander of Cotiaeum or Titus Prokul. They forced their pupils to read literature, memorize passages from Latin and Greek authors, to make speeches published by them, and then to disassemble. For example, Marcus had to come up with the text of Cato's speech to the Senate. Or an obituary for the Spartan king Leonid, who died in battle with the Persians.

Grammar exercises awakened the imagination, seemed to Marcus interesting, but Diognetus ridiculed them.

This tall, with a large forehead, sinewy artist, in general turned out to be a great skeptic. Marcus suspected that in Greece Diognetus attended a school of cynics21 and therefore wore a long uncombed beard, a simple squalid cloak. Laughing, he said of himself that he lived like a dog and that he was free from possessing useless things. “I am a true dog,” he grinned.

From him, Marcus learned that only strong personalities, heroes who were not afraid of anything but the gods could trust people. That's why the less you trust, the stronger you become. That's the paradox. Especially it is impossible to rely on magicians, on all sorts of fortune-tellers and broadcasters, who are the real charlatans, because they have appropriated the right of predictions belonging only to the Parks.22 “Their spells are a pittance,” Diognetus said of them harshly and mockingly, “they should be driven away like dirty and smelly dogs, plagued sick.”

Learning about Marcus's long-standing addiction to quail breeding, the free artist-philosopher ruthlessly ridiculed this boyish fascination. The harmless birds made him laugh contemptuously. “Philosophers,” he said morally, “don't breed birds, they eat them.”

Yes, Diognetus taught him a lot besides painting. Because of him, Marcus began to eat only bread and sleep on the floor, on hard skins, because his teacher went through it, and so were real Hellenics brought up.

Perhaps the fascination with cynics had gone too far. Like all boys his age, Marcus was too trusting and malleable to someone else's influence. He turned into soft clay in the hands of a Greek sculptor. It would be nice if these hands were worthy, noble, but not the hands of a cynic philosopher.

No, the strict and attentive Domitia Lucilla did not want her child to become a dog. Into a senator, consul, worthy son of Rome—yes. But into a dog—absolutely not! Diognetus's influence on Marcus seemed too aggressive, premature, and ultimately unnecessary.

She turned to Regin, who recognized her arguments quite fairly, and the artist-philosopher was dismissed from training. However, Marcus took the news quite calmly. By that time, he had already gained a youthful fascination with poverty, when the real world, nature looks like the antipode of patrician life and its inherent luxury, when it seems that rational simplicity is a certain meaning, and material poverty does not mean spiritual poverty.

However, the philosophy of the dog Diognetus was not in vain. Somewhere in the back of his mind this philosophy firmly sat, languished, raising difficult questions. She, this philosophy, could be an antidote to the life surrounding him. Just as King Bosporus Mithridates took poison in small doses not to be poisoned, Diognetus's views could relieve the feeling of the hardships and injustices of being.

But not now—the mother decided. Someday in the future, perhaps he would remember the words of the rebel.

20

Citharode was a classical Greek professional performer (singer) of the cithara.

21

Cynic (from the Greek dog) is one of the Greek philosophical schools, followers of Socrates, who preached simplicity, escape from conventions.

22

Parks are the Roman goddesses of fate.