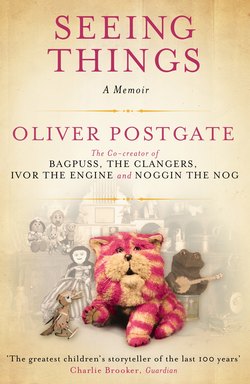

Читать книгу Seeing Things - Oliver Postgate - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

III. Grandad.

ОглавлениеPoor people were George Lansbury’s life. He was a founder member of the Labour Party, a militant pacifist, a lifelong campaigner for social justice who had become a much loved and revered figure, known as the uncrowned king of London’s East End. He it was who, accompanied by a brass band, had led the whole of the Poplar Borough Council to the High Court and on to prison, for refusing to implement the Means Test.

My mother Daisy was George’s seventh child (he had twelve in all) and she was brought up in ‘the movement’, where there was exciting work for all to do, including, for her, the task of impersonating, and being arrested for, Dorothy Pankhurst, the Suffragette leader.

My father, Raymond Postgate, who came from a formidably academic family, had turned against the academic life and had embraced socialism. He became a conscientious objector in the 1914–18 war, and was imprisoned and disowned by his father. He went to work for George Lansbury when he was editor of the Daily Herald, and married his secretary, and daughter, Daisy.

Grandad played an important part in our lives. Well, no, he didn’t exactly play a part, he was just there, a godlike personage hovering somewhere above us, likely to appear unexpectedly at any moment. I can see him standing in the doorway. He was huge. His bowler hat over his big white-whiskered face and massive black overcoat completely filled the door. He also had the largest ears I have ever seen. They didn’t stick out, they just covered a large area. I distinctly remember sitting on his knee and admiring them.

I already knew that Grandad was an important man, both in the family and in the world, but I didn’t know that he was a truly great man, nor that he would one day stand up in the House of Commons, reprove Winston Churchill for behaving like God Almighty and tell him to hold his tongue.

Once or twice Daisy took us to the House of Commons to see Grandad at work. The great palace was guarded by policemen but they each greeted Daisy by name and had a joke with her as we passed. Daisy walked through the sombrely magnificent halls and corridors of the House as if she lived there, and at every corner the officers smiled at her and spoke. I felt very proud.

Grandad was pleased to see us and took us all to tea on the terrace that overlooked the Thames. From there we watched the tugboats pulling lines of barges loaded high with planks of yellow wood. Grandad knew the names of the timber merchants and where the cargoes were going. I was very impressed by that but I also remember feeling a bit anxious about my important grandfather, sitting on the terrace having tea with us. It occurred to me that he was supposed to be in Parliament making laws, not wasting his time having tea with children. I raised this point with him and he took me into an inner hall of the tearoom and showed me a machine that was making ticking noises in short bursts and issuing paper tape. He lifted a piece of the tape and read it to me. Apparently it told him what was going on in the Chamber. He explained that he was allowed to go wherever he liked whenever he liked so long as he came and looked at the tape now and then to see what was going on, and if he was really needed in the Chamber to vote, a Division Bell would be rung to tell him it was time for him to go back in.

Once we actually went into the Commons Chamber to hear part of a debate. Daisy took us up into the Visitors’ Gallery, from where we looked down on the lines of green leather benches and saw a few Members sitting here and there. We saw the golden mace on the table and the Speaker on his throne, wearing a wig.

Daisy shushed us because something was happening. A voice muttered: ‘Mr Lansbury’ and I saw Grandad rise quite slowly and look around. I was so nervous for him I felt quite sick, but he seemed perfectly at ease as he began to speak. At first he spoke quietly, but then he gradually warmed to his work and his voice swelled to a sort of musical baying, which caught and carried my imagination along and would perhaps have moved me greatly if I had had the slightest idea what he was on about. Then, quite suddenly, he stopped and sat down. Amazingly, there was no applause or cheering. A few Members shifted the way they were sitting, and grunted. Then one of them, who seemed a bit angry, jumped up and began to yap like a terrier. That caused several of the Members to get up and, rather rudely I thought, walk straight out. The debate proceeded, but we didn’t stay.

My grandfather’s work in Parliament, making laws, seemed to me very august and remote from our own lives, but at other times and places we had a real part to play. In his capacity as First Commissioner of Works Grandad often had to attend ceremonial engagements. As these tended to be a bit solemn he liked to bring along a grandchild to lighten the proceedings and do small tasks, like cutting tapes.

I had the honour of assisting him at the opening of Lansbury’s Lido, a section of the Serpentine lake in Hyde Park which he had had adapted for the people of London to swim in. On this occasion I became a shade over-excited and inaugurated the swimming season myself by falling in, a gesture which was much appreciated by the onlookers, less so by my mother who had to borrow a towel from the changing-rooms to dry me.

By far the most alarming thing that had ever happened in my short life took place by accident on May Day in, I guess, 1931. There was, as always, a great rally in Hyde Park, at which, as always, George gave one of his huge rousing speeches that was received rapturously by an enthusiastic, loving crowd. At some point, after he had finished speaking and was leaving, I became separated from the party. The situation was that Daisy and Grandad were in a taxi with the windows open and I was on the grass about twenty feet away from them. This would have been no problem if I hadn’t been stuck in the middle of a solid cheering crowd that was mobbing the taxi to shake his hand. The crowd was shouting: ‘Good Old George!’ George was shouting: ‘Thank you, Brothers and Sisters!’ and: ‘Keep up the good work!’ My mother was shouting: ‘That’s my son over there!’ and I was shouting: ‘Help!’ I was only at waist-height in a tight press of people that was moving as a single cheering mass, carrying me with it. I had to hang on to the arm of the man beside me to save myself from going under and being trampled.

By pure good luck the man saw me and caught my mother’s eye. In an instant I was lifted bodily into the air and passed from hand to hand like a long parcel over the heads of the cheering crowd, to be posted head-first in through the window of the taxi, amid laughter and cheers of relief from the crowd, and tears of fury from my mother.