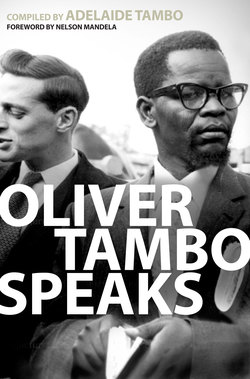

Читать книгу Oliver Tambo Speaks - Oliver Tambo - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеOliver Tambo was born into a modest peasant household in Bizana in the Transkei on 27 October 1917. He began his education at mission schools in the area of Flagstaff and with missionary sponsorship went on to St. Peter’s Secondary School in Johannesburg, matriculating with a first class pass in 1938. Awarded a scholarship, he studied at Fort Hare University College, a forcing ground for the training of African leaders in South Africa and abroad. It was there that Tambo first met Nelson Mandela, one year his senior. They cut their teeth in student politics and formed a close relationship that was to lead to a legal partnership in Johannesburg in 1952. Tambo graduated with a B.Sc. in 1941, but stayed on for a Diploma in Education only to be expelled during a students’ strike in 1942. This did not prevent him from taking up a post as a science and mathematics teacher at St Peter’s, his old school (1943-47). There he became acquainted with three fellow teachers who were to play important roles in the African National Congress: Lembede, Mbatha, and Mda. He also renewed his friendship with Mandela, who had moved to Johannesburg to study law. In 1944 they became, with others including Walter Sisulu, founder members of the ANC Youth League.

Tambo, Mandela and Sisulu were the most prominent founding members of the ANC Youth League and all went on to hold leading posts in the ANC. In December 1949, Tambo and seven other Youth Leaguers – including Walter Sisulu who became Secretary-General – were first elected to the National Executive. This group shaped ANC philosophy and direction in important ways. It was the Youth League’s “Programme of Action”, adopted as the ANC’s policy in 1949, that prepared the way for civil disobedience against the apartheid regime in the 1950s. It was their leadership that directed the Defiance Campaign in 1952 as a result of which over 8 000 volunteers were imprisoned for defying six selected apartheid laws. It was their shift from an exclusive African nationalism that prepared the ground for the Congress Alliance (with its symbol of a wheel with four spokes) of the four organisations: African National Congress, South African Indian Congress (SAIC), South African Coloured People’s Organisation (SACPO) and South African Congress of Democrats (SACOD). And it was the ANC’s guiding principles that created the mass movement represented by some 3 000 delegates at the Congress of the People at Kliptown on 25-26 June 1955.

When the Freedom Charter was adopted at Kliptown, Tambo was the Acting Secretary-General of the ANC. He had become Acting Secretary-General in August 1954, when Sisulu was served with a banning order and required to resign from the ANC.

Although Tambo was restricted at the same time to the magisterial districts of Benoni and Johannesburg for two years and prohibited from attending gatherings, he was not required to resign and was able to guide the ANC in the campaigns against the Western Areas removals and the introduction of Bantu Education. In December 1955, Tambo was formally elected Secretary-General, a post he held until 1958.

After the Congress of the People, the Congress Alliance gained a mass following and an organised presence in every African township throughout the country. It now faced state repression on a new scale and in a new form. In December 1956, 156 leaders of all races were arrested and charged under the Suppression of Communism Act with a treasonable conspiracy to overthrow the government. Tambo was amongst them. The preliminary examination in the Treason Trial began in January 1957, but charges were dropped in stages against the majority of the accused until only 30 remained on trial. Charges against Tambo were withdrawn on 17 December 1957. The trial dragged on for four and a half years, as the prosecution tried and failed to show the policy of the ANC to be one of violence. The final 30 accused were acquitted on all counts in March 1961.

During the period of the trial, the state enforced its own form of institutional violence against the movement and indeed all protesters. There was repression in 1957 when Bantu authorities were enforced in Zeerust and women were ordered to carry passes. There was more repression in 1958 with the enforcement of cattle culling in Sekhukhuneland, in 1959 when the people of Cato Manor protested against pass raids, and in 1960 when the government attempted to impose Bantu authorities in Pondoland. And as the defence was about to begin presenting its case in March 1960, the trial was disrupted by massive police action at the time of the Sharpeville shootings and the declaration of a State of Emergency.

In December 1958, Luthuli was elected President-General of the ANC for a third time, Tambo was elected to the post of Deputy President-General and Duma Nokwe became Secretary-General. But a group of separatist nationalists emerged in the organisation. Their leader, Robert Sobukwe, argued that the only people who really wanted change in South Africa were Africans, whose material conditions were the worst of all. Consequently, in his view, co-operation with whites was unwarranted. He also rejected any form of association with communists, alleging that their influence in the Congress Alliance had led to the watering down of the 1949 Programme of Action. The emergence of this group led to the formation of the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC) in April 1958.

The ANC decided to launch a campaign against passes on 31 March 1960, but they were upstaged by the PAC who began their campaign ten days earlier. The state reacted with more violence. In the Sharpeville massacre 69 were killed and 180 wounded. The ANC called a nationwide protest strike for 28 March. The state responded by declaring a State of Emergency on 30 March and detaining Luthuli and 2 000 other activists, a detention which lasted for five months. Some evaded the police and core groups of the ANC and SACP were established underground which rebuilt an active national network. Ruth Mompati, Moses Kotane, Michael Harmel and Ben Turok, amongst others, survived intensive police searches. Meanwhile, Oliver Tambo slipped across the Bechuanaland border to rouse worldwide protest. He was in Accra, Ghana, on 8 April when he heard that both the ANC and the PAC had been banned.

Mandela summed up the politics of the 1950s in these words:

During the last ten years the African people in South Africa have fought many freedom battles, involving civil disobedience, strikes, protest marches, boycotts and demonstrations of all kinds. In all these campaigns we repeatedly stressed the importance of discipline, peaceful and non-violent struggle. We did so, firstly, because we felt that there were still opportunities for peaceful struggle and we sincerely worked for peaceful changes. Secondly, we did not want to expose our people to situations where they might become easy targets for the trigger-happy police of South Africa. But the situation has now radically altered.

South Africa is now a land ruled by the gun.

(N Mandela, No Easy Walk to Freedom, 1965, p.119)

The stormy 1950s tested the ANC leadership fully. It was a decade of transition from protest politics to mass resistance which had to be guided skilfully by a leadership itself undergoing profound change. Tambo’s steady rise to the most senior positions was indicative of his responsiveness to the increasingly serious political crisis in the country and a recognition of growing confidence in his calm but committed leadership.