Читать книгу In the Balance of Power - Omar H. Ali - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Blacks have tended to be loyal to the two major parties. However, specific circumstances have led to active African-American support of third parties. When the two major parties reject African Americans’ political goal of inclusion, African Americans seek other political allies.

Michael C. Dawson, Behind the Mule: Race and Class in African-American Politics1

Throughout the history of the United States, African Americans have catalyzed movements for the expansion of democracy, social justice, and economic and political reform. Since the mid-nineteenth century, African Americans have done so through a range of independent political tactics, including creating or joining existing third parties, supporting insurgent or independent candidates, running fusion campaigns, and lobbying elected officials with the backing of various alliances and organizations. That is, there has been an undercurrent of political independence among African Americans since the nineteenth century, even as most black voters have aligned themselves with one of the two major parties: the Republican Party from the time of the Civil War to the New Deal; and the Democratic Party since the New Deal, and especially since the height of the modern civil rights movement.2 In our post–civil rights era of pandemics and political uncertainties, there are also new possibilities. Younger voters, less connected to the old-guard leadership of the civil rights movement, are increasingly self-identifying as independent—that is, neither as Democrats nor as Republicans—and they are doing so at record levels. A recent poll conducted by Tufts University notes that upwards of 44 percent of 18 to 24 year-olds identify as independent; meanwhile, Pew Research Center surveys show that over one in four African Americans across all age groups are consistently declaring their independence.3

To be sure, life in the United States will never be the same in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has ravaged so many lives, devastated so many communities, and upended the nation’s economy. A disproportionate number of black people have died in the pandemic—a function of widespread poverty among African Americans resulting from slavery, Jim Crow, and ongoing forms of institutional racism towards black and poor people.4 Tragically, partisanship contributed to the government’s failure to act quickly and decisively in the face of COVID-19. But the arc of history also provides some clues of what may come with regards to African American politics even as the pandemic continues in full force at the time of this writing. As the University of Chicago political scientist Michael Dawson notes, African Americans have worked to advance their political and economic interests by supporting third parties and creating new alliances. In doing so they have brought about some of the most basic and farthest-reaching changes in the republic: the abolition of slavery, the expansion of the right to vote, and the enactment and enforcement of civil rights. What happens going forward is not known. What we do know is that independent black leaders and their allies, joined by masses of ordinary African Americans, have not only served as a moral compass for the nation, but an organizing political force for progressive change.5

Today, increasing numbers of black voters are among the tens of millions of people, from a range of backgrounds and from across the ideological spectrum, who view themselves as politically independent. Gallup Polls indicate a steady rise of non–major party political identification among all voters since the late 1980s: from 32 percent in 1988 to 42 percent in 2019.6 National opinion polls since the 1990s indicate that up to 30 percent of all African Americans identify themselves as politically independent.7 Notably, the category of “pure independents” created by pollsters and political scientists (that is, those who do not “lean” toward one or the other major-party when asked how they would vote after having first identified themselves as independent) reveals a profound bias against who independents are, now a plurality of voters in the United States. In this view, independents are effectively a “myth,” that is, closet-partisans, confused, or politically immature.8 However, when asked, independents say they want to be respected and recognized as independents (they do not fit into the partisan boxes which demand party loyalty).9 Justifying the approximate ten percent who are supposedly the “pure independents” (bolstering the notion that the vast majority of eligible voters are in support of the current bipartisan system) misses an obvious point: that if given only two (if that) actual choices on the ballot, then voters might choose one, or not vote at all—which is in fact what voter behavior consistently shows. Perhaps we should look to younger voters for what might lie on the horizon. Indeed, young black voters, like Millennials in general, identify at even higher levels as independent than do older cohorts. A 2019 University of Chicago–affiliated survey noted that upwards of 38 percent of African Americans eighteen to thirty-six years of age did not identify with the two major parties.10 These Americans are part of an emerging movement of African Americans and white independents comprising black and independent alliances. Most notably, in 2008, a black and independent alliance rallied around the insurgent candidacy of Senator Barack Obama in his bid to become president of the United States.11

Increasingly less tied to the Democratic Party, black voters have been looking for new electoral options and allies in the face of bipartisan hegemony, ongoing poverty, and racism. The Black Lives Matter uprisings, potent political and cultural expressions, are manifestations of the search and demand for social justice in the United States among African Americans, especially younger African Americans. When this book first came out twelve years ago, 66 percent of all Americans believed that the nation was on “the wrong track.”12 The latest Pew Research Center poll shows a historic low in terms of public trust in government: fully 83 percent of Americans lack confidence in government doing “what is right.”13 Among African Americans, the feeling and experiences of having been failed or betrayed are especially poignant and painful. Whether it is the failure of the health care system, the public schools, or the economy—despite the heroic efforts of rank-and-file nurses, doctors, teachers, and other workers—there is widespread recognition that the two-party establishment has not been willing or is unable to effectively serve the best interests of ordinary people.14 Partisanship, institutionalized in the bipartisan arrangement of the Democratic and Republican parties that rule the nation (despite these organizations being private, not public entities, although they create rules and regulations to benefit themselves using taxpayer dollars), either prevents or deters innovation in policies or practices that might otherwise effectively address the myriad challenges facing the nation as a whole and black communities in particular. Panning out, American history reveals that progressive change—social, political, and economic justice and reform—has always come through the interplay of outsider forces and insider forces, which is why independent political action remains critical to the development of the nation as a whole.

✓ ✓ ✓

African Americans have expressed their political independence in a number of ways since the late 1980s. In 1988, when Rev. Jesse Jackson ran as an insurgent presidential candidate for the nomination of the Democratic Party, two out of three African Americans who voted for him in the primaries reported that they would have voted for him as an independent had he decided to run as one.15 He did not, but that year another African American did: Dr. Lenora Fulani, a developmental psychologist and educator, became not only the first African American but also the first woman to get on the ballot in all fifty states as a candidate for president. She ran as an independent.16 Four years later, in 1992, the New York Times reported that 7 percent of black voters had cast their ballots for H. Ross Perot, a white Texas billionaire who, like Fulani in 1988, defied the two major parties but, unlike the black independent, had a $73 million war chest with which to advance his campaign.17 Nearly twenty million voters, or approximately 19 percent of the electorate, would cast their votes for Perot—the largest number of votes cast for an independent in U.S. history—of which over half a million votes came from African Americans.18 A CBS News poll conducted in May 1992, during the primaries, found that upwards of 12 percent of African Americans said they would vote for Perot over the Democratic and Republican candidates, reflecting surprising support for an independent presidential candidate among black voters at that point in the presidential race; the Los Angeles Times reported Perot drawing up to 18 percent support among African Americans in California.19 In New York, Rev. Calvin Butts, pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem (a position previously held by the late Democratic Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr., who had been elected with the support of the American Labor Party), gave an early endorsement to Perot, commenting that the independent represented “a viable alternative for black voters.”20

Within days of Butts’s endorsement, the pastor came under heavy criticism from New York’s black Democratic leadership, headed by Congressman Charles Rangel. Indeed, the attacks on Perot came from across the bipartisan establishment, black and white. From the beginning of his campaign, the Texan was ridiculed by virtually every major liberal and conservative analyst, who fixated on his personal attributes—his diminutive stature, “folksy” style of speaking, and ubiquitous graphs and charts—instead of seriously engaging the question of why millions of people were interested in voting for him.21 Whether “sick of the Democrats and Republicans,” stating that “the politicians are corrupt,” or offering more nuanced reasons for why they were voting for Perot, Americans were exercising their independence. In the months and years after the election, the two major parties would attempt to contain and dismiss the voter rebellion: the federal budget was quickly balanced through bipartisan agreement (one of Perot’s concerns was the federal deficit), and the Republicans issued a “Contract with America,” containing sweeping promises of political reforms (the overriding message of his campaign). During the next election, Perot, the symbol of the 1992 voter revolt, was excluded from the national presidential debates.22

Throughout the 1990s, black and white voters continued to assert their independence—passing term limits wherever initiatives and referendums were possible, recalling elected officials, voting for local independents and third-party candidates, and withholding votes for major-party candidates.23 Beginning in Colorado, a largely unreported voter initiative was put on the state ballot to limit congressional terms (four terms in the House and two terms in the Senate). The measure passed with 71 percent of the vote in 1992. Subsequently, a movement under the direction of the organization U.S. Term Limits led to the adoption in fourteen states of term limits on congressional representatives, approved with an average of 67 percent support. According to exit polls in New York, “A clear majority of black voters want term limits.”24 At a black political convention held in Manhattan on April 8, 1995, three hundred African Americans, from a range of backgrounds and political perspectives, met and endorsed term limits for all elected officials and judges.25 There were other signs of discontent and expressions of political independence among African Americans. In the 1997 gubernatorial race in Virginia, the Democrat, Donald Beyer, received 80 percent of the black vote, rather than the usual 95 percent, and, as a result, lost to the Republican candidate.26 Former Democratic governor Doug Wilder, the state’s first African American governor, had refused to endorse Beyer, remaining neutral instead.

One of the clearest expressions of black voters’ independence came in the form of disaffection from the Democratic Party during the 2005 mayoral election in New York City. In the fall of that year, media businessman and billionaire Michael Bloomberg—running a fusion campaign on the Republican and Independence Party lines—was reelected mayor of the city with 47 percent of New York’s African American vote.27 Like Perot, he spent tens of millions of dollars of his own money to run (as he would in his failed bid for the Democratic Party presidential nomination in 2020). His most outspoken black supporter for his mayoral run, Fulani, had helped establish the Independence Party in the wake of the 1992 election. With almost no direct backing from Bloomberg himself, she led volunteers across New York City to rally support for his candidacy. Concentrating in Harlem and parts of Brooklyn and Queens, the Independence Party called on African Americans to vote for Bloomberg on column “C” (the column on the ballot where New Yorkers could vote for Bloomberg as an independent—column “A” being Democrat and “B” being Republican). In 2001, during his previous bid for mayor, Bloomberg had promised the Independence Party, whose ballot line he sought, to push for an enactment of nonpartisan municipal elections using the city’s initiative and referendum if elected. That year the Independence Party, with over 59,000 votes, gave Bloomberg his margin of victory. Keeping his promise, Bloomberg set up a series of Charter Revision commissions in which hundreds of New Yorkers had a chance to testify both for and against placing nonpartisan municipal elections on the ballot; the measure was ultimately defeated at the polls, largely at the hands of the Democratic Party, which strongly opposed it. But in 2005 the outpouring of support among African Americans would not only prove a serious indictment of the Democratic Party but point to the changing ways in which black New Yorkers were beginning to view themselves relative to both major parties.28 As John P. Avalon wrote in the New York Sun, “something is happening in the African-American community. . . . The diversification of the black community economically and politically is changing the landscape. One recent sign of this is the surprising amount of support for Mayor Bloomberg among African American voters. . . . A recent WNBC/Marist poll showed the mayor receiving 50% support from black voters.” Avalon further noted, “The growing [independent black] trend is broad as well as deep—in 1998 only 5% of African American voters between the age of 51 and 64 identified as independents, but by 2002 that number increased fourfold to 21%.”29

It has taken the financial resources of white billionaire businessmen in conjunction with the grassroots organization of insurgent and independent black leaders for African Americans to help challenge the bipartisan establishment.30 Millions of dollars are needed to run television and radio advertisements, conduct telephone banking, retain legal expertise, and petition drives, all of which are necessary to begin to compete effectively in the electoral arena. The laws and related rules governing the electoral process (written and passed by the two major parties’ elected representatives) are specifically designed to keep the Democratic and Republican parties in power: restrictive ballot access, single-member districting, gerrymandering, inequitable campaign finance laws, and discrimination against non–major party candidates in televised debates combine to marginalize even the wealthiest citizens. Underscoring the state of American democracy, when Fulani was asked by a reporter to reflect on what was more difficult in her run for president, being black or being a woman, she poignantly noted that “it was being an independent.”

The election of President Obama to the highest office in the land as a Democrat was surely a milestone in the history of the United States; it was also the culmination of decades of on-the-ground organizing by ordinary people, many of them black independents, such as Fulani and her associates, in face of Democratic Party opposition. The tension remains (as Jacqueline Salit describes in the new Afterword to this book). One of the ways it took shape was in the 2016 presidential cycle. Black voters displayed diminishing support for the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate, Senator Hillary Clinton. Early voting in battleground states, including North Carolina and Florida, revealed a 14 percent decrease in turnout in early voting among black voters, as upwards of two million voters, including many black voters, chose not to vote for the Democratic Party nominee in the general election despite strong appeals by President Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama on behalf of Clinton. Overall black voter turnout for the Democratic Party in 2016 dropped five percentage points from 2012 (with insurgent Democratic candidate Senator Bernie Sanders being bullied out of the nomination by what, by any measure, are strikingly undemocratic nominating procedures that give “superdelegates” extraordinary power to override the will of rank-and-file delegates within the party). Donald Trump was elected president to the stunned surprise of the nation—the same nation that had reelected Obama four years earlier. Many Democrats began to call for impeachment, which eventually came to pass. By 2018, however, African Americans were once again joined by white independents to back Democratic congressional candidates—this time by a margin of twelve points, revealing the critical role of African Americans when mobilized. In these ways, and other ways, African Americans have been a factor in the balance of power.

✓ ✓ ✓

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 initiated enforcement mechanisms (albeit, at times, unevenly applied) to protect African Americans’ right to vote, but the question for many voters and would-be-voters remains: What meaningful choices are there in a largely bipartisan electoral system? That is, what political options are there if one is not in favor of the dominant policies or practices of the Democratic or Republican parties?

In 2004, independent presidential candidate Ralph Nader, the only antiwar candidate with national stature (Democratic presidential candidate Senator John Kerry of Massachusetts had voted for congressional war appropriations for the war in Iraq), was, at the instigation of the Democratic National Committee, removed from the ballot in more than a dozen states.31 The Democrats and their Republican counterparts who shared control of the Commission on Presidential Debates would also exclude Nader from the presidential debates. In an environment of such heavy-handed bipartisan rule, when independent and third-party candidates holding dissenting views are blocked from either appearing on the ballot or participating in televised candidate debates, political opposition to the major parties is marginalized to the point of virtual nonexistence.32 Bipartisan constraints have consistently stymied the growth of third-party and individual independent campaigns since the early part of the nineteenth century, ultimately providing few options for voters. African Americans in the antebellum North who were somehow able to meet the property and residency eligibility requirements to vote (as in New York, starting in 1821), or had not been excluded from the vote by statute (as in Michigan, starting in 1837, or Pennsylvania, starting in 1838), often had no choices in the electoral arena.33 From the 1830s to the 1850s, the vast majority of candidates from the two major parties—at that time, the Democratic and Whig parties—were proslavery, or silent on the issue.34 If one was against slavery, the electoral arena was a limited venue for expressing one’s views—that is, until black and white abolitionists forced the issue of slavery and its abolition onto public stages through mass campaigns by calling on candidates and elected officials to take a position. These abolitionists formed the antislavery Liberty Party, running candidates of their own. In the century thereafter, African Americans confronted a new bipartisan establishment, when the Democratic- and Republican-controlled government was largely unwilling to enforce the constitutional rights of black men and women in the Jim Crow South.

In the current era, despite the legal gains of the modern civil rights movement, which successfully pressed elected representatives to pass federal legislation reaffirming the civil and political rights of African Americans (the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965), elements of a new Jim Crow have become embedded in the political process (that is, legalized forms of marginalization and disfranchisement not based on race but on non–major-party registration).35 Independents in the twenty-first century, regardless of race, ethnicity, socioeconomic background, or political ideology, face a kind of second-class citizenship in the electoral arena. They are legally and institutionally marginalized, not only in terms of ballot access but by their exclusion from televised debates through gerrymandering and the actions of bipartisan (as opposed to nonpartisan) election regulatory bodies—from the Federal Election Commission to the Commission on Presidential Debates—favoring the two major parties and their candidates.36 Bipartisan restrictions to the ballot not only limit the choices available to voters but, as a consequence, determine the policies and practices that flow from having candidates elected from such a limited set of options. Such restrictions also discourage voter participation. Moreover, as Steven Rosenstone, Roy Behr, and Edward Lazarus note in Third Parties in America: Citizen Response to Major Party Failure, the obstacles faced by independents are not only legal but sociocultural. They write: “It is an extraordinary act for Americans to vote for a third party candidate. . . . To vote for a third party, citizens must repudiate much of what they have learned and grown to accept as appropriate political behavior, they must often endure ridicule and harassment . . . , and they must accept that their candidate has no hope of winning.”37

Since the mid-1980s, and in the face of legal and socio-cultural obstacles faced by independents, the percentage of voters—black and white, liberal and conservative—who either describe themselves as independent or register to vote as unaffiliated or with a non–major party has steadily grown.38 The percentage of voters who registered as neither Democrat nor Republican between 1984 and 2004, for example, more than doubled, from 10.2 percent to 21.9 percent.39 It is a pattern that continues locally and across the nation, with some states registering faster growth than others; North Carolina’s independents have been among the fastest-growing group of registered voters.40 Meanwhile, Gallup polls indicate that 42 percent of Americans self-identify as independent, up from approximately 29 percent 40 years ago. So, while the percentage of Americans participating in elections is largely holding at slightly over half of the electorate, even as the total number of voters increases—138 million people voted in the 2016 presidential election, compared to 122 million in the 2004 presidential election, and 111 million in 2000—an ever-larger percentage are positively identifying themselves as independents or registering as such.41

Regarding African Americans—who, as a whole, have proven to be the most loyal constituency to the Democratic Party, with the majority identifying themselves as Democrats since the mid-1960s—there appears to have been a political transformation. David Bositis of the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies notes, “The votes cast by African Americans in 2004 showed them to be less Democratic in their partisanship than they had been in 2000.”42 While 14.8 percent of African Americans identified themselves as politically independent in 1997, by 2005 that number had increased to at least 25.9 percent. If we add the 5 percent of those who responded either “other” or “no preference” to the 25.9 percent of those who said that they were “independent,” the percentage of African Americans who did not identify with either major party was 30.9 percent.43

✓ ✓ ✓

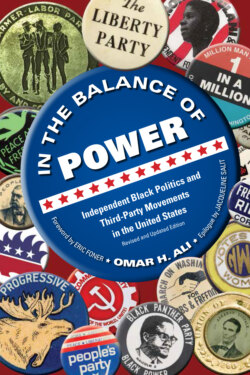

Perceptible signs of dealignment among African Americans relative to the Democratic Party have prompted the examination in this book of the history of independent black politics and third-party movements. Not since Hanes Walton Jr.’s Black Political Parties: An Historical and Political Analysis, published in 1972, has a book-length work been devoted to the subject of African Americans and third parties.44 While a number of key studies on black politics in U.S. history have appeared since that time, including award-winning books by Michael Dawson and Steven Hahn, none focus on third parties and independent politics per se.45 The present study therefore details how African Americans have used independent political tactics to advance their black political and economic interests.46 Since the middle of the nineteenth century, third parties have provided a way for African Americans (among other disaffected and marginalized groups) to apply pressure on the ruling parties. Under ongoing, although not necessarily consistent, outside pressure, the major parties have, in turn, adopted policies initially raised and fought for by independents into their own party planks, and have sponsored legislation accordingly. In the nineteenth century, members of the Liberty Party sought the immediate abolition of slavery; radical Republicans pushed for the extension of black voting rights; and Black Populists—through the Colored Farmers’ Alliance and then the People’s Party—demanded that the government provide economic relief and political reform. In the twentieth century, Socialists, Progressives, and Communists, each in their own way, helped (albeit under the authority of the Democratic Party) to usher in the modern welfare state with measures such as social security and a minimum wage enacted into law. Meanwhile the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, among other black-led organizations and parties, demanded that the government protect African Americans’ civil and political rights. Black independents, such as the Harlem physician Dr. Jessie Fields, like many of their counterparts from the past, continue to call for a level electoral playing field, with the appropriate recognition and respect that any other group of citizens should enjoy.

The pioneering work of black independents is the focus and thread in this historical study. This is in contrast to the way American political history is usually detailed and analyzed, which is by focusing on the major parties and their political leaders. Building third parties and independent political movements has been a potent yet underappreciated way that African Americans have effected changes, ultimately including extending citizenship, gaining the vote, desegregating public facilities, providing economic relief, and protecting black civil and political rights. African Americans have also chosen to work solely within the major parties—and indeed, those parties have always had dissenting voices within their ranks—but it remains the case that without ongoing independent political pressure, progressive legislative changes would likely not have been made. In other words, and more accurately, it has been a combination of outside-inside (inside-outside) movement-building, political action, and legislative negotiating that has produced change in the nation. The work of black independents, among other independents, in the electoral arena has therefore been an essential part of the development of American democracy.

A final note. After we, as a society, emerge from the mass protests and pandemic underway, we will have been changed in fundamentally unforeseeable ways. The conditions in which we find ourselves are transforming as this second edition goes to press. What we do and how we are able to reconstruct, remake, and reimagine our nation’s political institutions, our economy, and our culture are up to the American people—as it has been the case in other times of crises and catastrophes.47 Are new, nonpartisan forms of political empowerment and coalitions possible to move the country forward in more democratic and developmental ways? Perhaps. If history is any indicator, the voices of African Americans, and independent black leadership in particular, will be key to our recovery and renewal.