Читать книгу The Natural Selection - Ona Russell - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

Tennessee, June 1925

The gold sealing wax was a nice touch, the professor thought, a little extra to show his apology was sincere. He gave the envelope a final, satisfied glance and slipped it under the chipped wooden door. In one quiet push it vanished, and so too any last faint traces of remorse.

He listened. Still no signs of life. He stole down the empty hall and exited the building, greeting the muggy dawn with a line from Nietzche, Hegel—one of the Germans, it didn’t really matter which—suddenly in his head: “What is right is what the individual asserts is right, but it is only right for him.” Precisely, he thought. Precisely. Of course, some rules were necessary; the mass of men couldn’t be trusted to think for themselves. Indeed, the professor had dedicated himself to reversing the damage the thinking of lesser minds had done. But the sentiment applied quite well to men compelled to live by a different code. Men like himself who were educated, admired and followed.

He smiled, imagining the objections of all those bleeding hearts. Wasn’t such a view contradictory? Didn’t it imply that the very deed he had just cleansed himself of could be worthy of punishment in someone else? Perhaps. But then the professor was, if nothing else, a man of contradictions. This morning it simply had been easier to explain them away. Everything seemed easier in the summer. Warmth might slacken the body, but it filled the spirit, leaving no barren space for doubt to creep in.

And so later that day, he strolled content and free in the college woods, only yards from campus, but worlds away. Believing he was alone, he inhaled deeply and loudly the honeysuckle bouquet, took in every hallowed branch of petal-like dogwood. Students would trample over this same path in only a few weeks, but for now, these were his woods. He loved this place. Of course, everyone else did too: his colleagues, students and neighbors, all staking their unearned claims to its quiet beauty. But his love came from deep within his veins—a love that stemmed from his family having once owned the very ground upon which he walked. Land for which his grandfather, a Confederate spy, gave his life.

The South. Another passion. Another contradiction. In the study of books, the professor was avant-garde, continuously pushing against the boundaries of convention, lecturing on the newest strains of literary criticism. “Literature should be judged on its own terms,” he boomed to the hall of young, adoring eyes, “not according to some rigid sense of morality.” But on the subject of his heritage, he was firm. Here, tradition was sacred, morality absolute. Right and wrong were literally divided into black and white.

As he forged deeper into the thicket, his thinning white hair beginning to mat with sweat, he thought, as he often did, of the need to restore order and erudition to the region. The South had been turned on its head since the Civil War, and he was committed to putting things—and people—back in their natural place. He was, he liked to tell himself, reclaiming the Golden Age.

In the pursuit of such a noble goal, there were bound to be casualties along the way, and today’s was not the first. Survival of the fittest, his trusted Darwin proclaimed. And so it was with particular pleasure that he took in nature’s best—the sheltering verdure, the familiar canopy of oaks, the gentle slope leading toward the creek whose clear water he would cup to his mouth.

But the professor was not, as he had thought, alone. Mirroring each turn, shadowing every step was someone following closely behind, silently, invisibly, until the moment was just right.

“Jesus Christ!”

“Hello Professor Manhoff,” the familiar voice said evenly.

“Oh, oh, hello there. My God, you scared the life out of me. What are you doing here? I thought you were . . .” And then a fleeting realization. For a moment, the corners of his mouth formed a slight grin of understanding until . . . the quiet rage . . . the gleaming barrel. He opened his mouth to speak, to plead for mercy. “No. Please. God.” But it was wasted breath. One shot rang out, clear and resonant, and he fell, heavy, into a bed of moss and branches. A bright pool of blood gathered in the full growth. It spread, feeding the soil and staining the land of his ancestors until, finally, the ceasing of his heart halted the flow. And then he was alone, truly alone in the college woods.

1

Sarah closed her book, drew back the miniature, velvet curtain and peeked out the window. Finally the flat, grassy checkerboard had given way to rolling hills, which, from the vantage point of the speeding Pan-American, appeared to fold in upon themselves like emerald waves in a land-locked sea. As the conductor strolled the aisles, bumping every now and then against the slumped shoulder of a half-dozing passenger, he announced that they had just entered Kentucky, halfway through the all-day ride from Toledo to Knoxville. Right on schedule, Sarah thought.

She leaned back and exhaled. Now she could relax. As long as she was in Ohio, she wasn’t free. Work could always track her down: dockets in need of review, people in need of counseling, each requiring her immediate attention. And memories. They seemed to find her, too, especially the ones she wished most to forget. But at last she’d managed to escape, each minute speeding farther away from it all. And up ahead lay the holiday she’d put off for years.

She glanced around and for the first time really noticed the car. How trains had changed. So modern! Not at all like the stuffy Victorian parlors they used to resemble. This was her first trip on the Pan, and now that they had crossed the state line she took in every detail. The black upholstered seats, the steel frame sheathed in glossy mahogany, the wide, carpeted aisles. Simple but elegant, with the exception of the portly man snoring across from her whom she was ready to clobber with her handbag.

One month. Four weeks. Thirty-one glorious days. Time to do with as she pleased. As her mind raced with the possibilities, she stretched her stockinged legs out as far as they could reach and closed her eyes. It would be hot, of course. Hot and muggy. But late breakfasts, hiking in the Smokies, a trip or two to the baths would balance out any ill effects. Besides, she’d just read that a little perspiration was good for the pores. And of course, there would be her cousin, Lena. Indeed, if Lena hadn’t invited her down, pleaded with her to visit, Sarah still might be cooped up in her office, attempting to finish the work that never really would get quite done.

Little Lena. Though ten years younger, a kindred spirit. The person Sarah might have been had she been blessed with the same opportunities. Imagine. Graduating from Vassar, with honors. And then landing a teaching job at Edenville College. Quite a feat for a woman. Unheard of for a Jew. Which is precisely why, Lena told Sarah, she believed she was hired. To be observed and poked at like a newly discovered species. If anyone could handle herself, though, it was Lena: brilliant, feisty and deceptively clever. Sarah suspected that in no time her cousin would have her colleagues so charmed, they’d have no choice but to abandon their experiment and simply let her do as she pleased.

The train slowed as it passed one of the many nondescript towns along its route, and Sarah picked up her book again, tracing her fingers along the cover. An outline of a simple, ivy-covered cottage, under which gleamed the gold embossed lettering: Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Despite its renown, Sarah had never read it. “Overly sentimental,” Obee had warned. “Moby Dick, my dear. Now that is a novel.” Uncharacteristic for Obee—Judge O’Donnell, that is—who usually touted his broad literary taste.

As the tip of her finger traced the line of the cottage, she let it trail down to the author’s name etched below: Harriet Beecher Stowe. A Northerner whose portrait of slavery was so powerful that Lincoln was said to have credited her with starting the Civil War. Sentimental? Perhaps. But Sarah wasn’t beyond judging for herself, especially now that she was traveling from one side of the former divide to the other. She turned to an earmarked page and read, silently mouthing the words:

I have tried—tried most faithfully, as a Christian woman should—to do my duty to these poor, simple, dependent creatures. I have cared for them, instructed them, watched over them, and known their little cares and joys, for years; and how can I ever hold up my head again among them, if, for the sake of paltry gain, we sell such a faithful, excellent, confiding creature as poor Tom.

“Excuse me, ma’am.” Sarah slowly raised her eyes. “Ma’am?” A tap on the shoulder now accompanied the smooth, low voice.

“Yes?” she said, craning her neck toward the passenger in the seat behind her.

“Pardon me. I’m sorry to bother you, but I couldn’t help notice your book.” The young man leaned so far over her seat Sarah thought he might fall onto her lap, and she instinctively shifted positions to spare herself. “You’ve read it?” she asked.

“Oh, yes. Quite a coincidence, in fact. You aren’t taking a class at the university, are you?”

“No,” she said, with a restrained smile, knowing full well he knew she was a tad too old to be sitting in any lecture hall. “Why do you ask?”

“Well, Mrs. Stowe isn’t often read for fun. Not these days, at any rate.”

“Really? I’m finding her fascinating.”

“I could only hope my students feel the same.”

“My goodness, you look like a student yourself. Where do you teach?”

He studied her for a moment and without asking, maneuvered himself in one rather clumsy half pirouette into the seat directly across from her. She had wanted to be alone, but now, like it or not, he was here. She smiled to herself and watched as he settled in. Up close he actually appeared even younger than Sarah initially thought. Twenty-one, twenty-three tops. Framed by angular, straw-colored eyebrows, his gaunt, narrow face and high cheekbones gave him a startled look, which intensified when he spoke. Handsome, in a struggling artist sort of way, especially with his rumpled white shirt, stained with a chunky remnant of what appeared to be mustard, and blond Byronic curls that crept haphazardly down his long neck.

“You know,” he said, “their stance against slavery was often theoretical.”

“Their?”

“Oh, I am sorry. There I go again. Starting in medias res.”

Sarah knew that meant “in the middle of things,” but noted that he didn’t seem to care if she did or not.

“Name’s Paul Jarvis. I’m a graduate student in history at UT, the University of Tennessee.” He took her hand and shook it vigorously. His palm was soft and moist, and Sarah quietly wiped his sweat off of her hand onto her dress. “I’ve been assigned my first lecture next week, and, to tell you the truth, I’m terribly nervous. An overview of Tennessee history.” He pointed to her book. “When I get to slavery, I’m going to discuss Mrs. Stowe a bit.”

Sarah nodded, observing his unlined face. No trace of nervousness there. She wished she could say the same of her own, which, she worried, manifested every harrowing moment of the last year.

Sarah cocked her head and twisted the long string of pearls that hung in a heavy loop around her delicate neck. “You know, Mr. Jarvis, my cousin, whom I’m actually on my way to visit, thinks Mrs. Stowe is terribly underrated. She’s a new hire in the English Department at Edenville,” Sarah said, puffing out her somewhat underdeveloped chest.

“Really? That is interesting!” he said, smiling broadly to reveal deep dimples and a slightly chipped front tooth. “What about you?”

“So far, so good. I need to read more to judge.”

“No, I mean what do you do?”

“Oh.” Sarah blushed and straightened in her seat. “I’m head of the Toledo Women’s Probate and Juvenile Courts.”

“My, that sounds impressive too. Seems like you’ve got something special runnin’ through that family blood of yours.”

He asked her to explain what her job entailed, which she did in the simplest of terms: “wills, property and marriage,” she said, not caring to elaborate upon the actual unpredictable and varied scope of her duties under the Honorable O’Brien O’Donnell.

“So, what is it you plan to discuss in this class of yours, Mr. Jarvis?” she asked, wanting nothing more than to avoid the topic of her own work. And that was all it took. Before she knew it, he was opening a worn leather satchel overflowing with notes and papers, though it still had room to hold a short, wooden pipe, already filled. He bit down on the tooth-marked stem and held it in his mouth in perfect suspension. “Do you mind?” he asked. She shook her head, and without hesitation he lit the aromatic substance, puffing in and out rapidly until it burned on its own. He closed his eyes and exhaled.

“Since you asked, ma’am, would you be at all interested in hearing a condensed version of my lecture? I could use a fresh set of ears and considering what you were reading . . . well, I’d forever be in your debt.”

Sarah raised one freshly plucked eyebrow and glanced down at her book. She hoped to have been further along, but for once there was no rush. “All right,” she said, with just a hint of resignation. “Mind you, I’m a tough critic.”

“You’re a peach.” He laid the smoldering pipe on the armrest and rearranged the papers until he was satisfied with the order, pulled himself up in his chair, and began.

“Now, I know most of y’all call Tennessee home. But it’s surprising how much we sometimes don’t know about the place where we live. So bear with me.”

Sarah found his folksy opening endearing, and nodded her head in encouragement. Even if she hadn’t, however, she probably would have reacted the same. She was, as everyone told her, a good listener. Really, she couldn’t imagine being otherwise in her line of work. She hated to hurt anyone unnecessarily, and there was nothing more hurtful than being ignored.

“Tennessee, the sixteenth state to enter the Union, has a long history of oppression. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson, the Tennessean who allegedly gave the state its name, signed the Indian Removal Act. Can anyone tell me what that was?”

Sarah was tempted to raise her hand. Fortunately she caught herself, for an invisible student had apparently already answered the question.

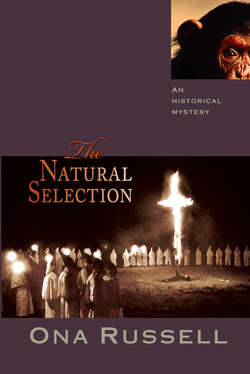

“That’s right,” Mr. Jarvis said. “It was the forced relocation of the Cherokee and other tribes from their southeastern homes to territories west of the Mississippi. ‘The Trail of Tears’ as it has been termed, borne of white supremacy and greed for land.” He relit his pipe and licked his lips. “It was also in Tennessee, in Pulaski, a small town in the middle of the state, that the Ku Klux Klan was later formed.”

Sarah shuddered. The KKK? Six months had passed but the mere mention of the name still nearly undid her. She felt for her rings and began to twist. One, two, three.

“With white hooded robes, rapes, whippings and murders as their calling cards, the group, which rapidly spread to other states, succeeded in instilling fear among Negroes and Union representatives, those they considered enemies of the Southern way of life. Though the organization disbanded during Reconstruction, it reconstituted and is now an even more intolerant group, widening its net of undesirables to include Catholics, immigrants and Jews.”

As if in perfect theatrical timing, the train jerked to the right, and Sarah’s stomach, already on edge, turned inside out.

“The group has become more powerful and currently has candidates on political tickets nationwide. The most, I might add,” his voice now bellowing, his eyes directly on Sarah, “in the North, in Indiana, just a skip and a jump from Ohio.”

He needn’t have gone to such dramatic measures. Sarah already knew about Senator Stevenson and his bunch of thugs. And she knew too, more intimately than he ever could have imagined, about the Klan’s presence in Ohio. In the last election, the Toledo chapter had tried its best to remove Obee from office, something that nearly cost him his sanity . . . and Sarah her life.

•••

Steadying herself as the train turned another hard corner, Sarah grabbed hold of the cool handle to the restroom door and locked herself inside. It was hard to maneuver in the cramped space, but she needed a private place to recover after Mr. Jarvis’ speech. Of course, she knew he was blissfully unaware of the turmoil he had stirred inside of her—how could he have known?—and she had made every attempt to happily congratulate him on a well-presented lecture. Now that she was alone, though, she let herself go. After a moment, her stomach eased a little and she ran the hot, mildly sulphuric water and lavender scented soap over her hands, splashing cupfuls onto her burning cheeks. By the time she dried off, steam had completely fogged up the small oval mirror hanging on the wall directly overhead and she wiped it with a towel until her image reappeared.

She let out a little self-deprecating laugh. Sarah knew that now that the past had resurfaced she couldn’t prevent it from playing itself out; she only hoped it wouldn’t carry her too far away. The stubborn past. Like a perpetually rewound film waiting for the next flip of the switch. She stared into the mirror, seeking her own reflection, but one by one the images came fast, stuck in time and place, blotting her out. Obee, weak and frail in his hospital bed, the blackmail note, horrible words and terrible threats, and always, the moment she thought she would die. Panic. Suffocating breath. Hands tightening around her throat. She felt them all now and had to pinch herself to stop from going any further.

Of course, Sarah was no stranger to murder. Counseling victim’s families, visiting perpetrators in prison, listening to innumerable attorneys prosecute and defend in its name. But until six months ago, it had always felt . . . distant. Then, suddenly, unexpectedly, death and fear grew close, hovering around her friends and family, haunting her dreams, until finally, she saw it, felt it, tasted it for herself.

Holding firmly to the basin’s rim, she breathed in deeply and exhaled. Whether fate, luck, or the grace of God had intervened Sarah wasn’t sure, but she reminded herself now that she had managed to escape. And that she had helped Obee, her boss, her mentor, her friend to regain his health and return to the Bench. She had found the strength, risen to the occasion.

Thinking of these things always calmed her nerves, and soon her hands dropped to her side, her breathing slowed, and she once again saw her own reflection before her. Her involvement in the matter had come at a stiff price, but she was alive and now determined to move forward. And Sarah reminded herself there was a reason she had come so close to death’s door. She was glad she had helped put things right, but she’d traveled too far afield. She wasn’t a detective. She was an officer of the court, and a good one at that. When she returned from her holiday, she would be so again. The more routine the case, the better.

Feeling steadier and stronger by the moment, Sarah reached into her purse and pulled out a small, gold compact. Normally, she wouldn’t have bothered—she could reapply the tiny amount of powder she used blindfolded—but since the events of last fall, she had become somewhat self-conscious about her appearance. Not about her so-called imperfections: the outward curve of her rather prominent nose, the slight gap in her front teeth, the tiny, half-moon scar on her left cheek. Those she had accepted long ago, had even grown to half-heartedly believe that they gave her the character everyone said they did. No, it was the loss of youth, or more precisely, no longer looking younger than her years, that had prompted vanity to rear its ugly head. Having been complimented on the trait so often, she had, even at forty, simply taken it for granted. Not any more. Not when nearly everyone she encountered offered instead their well-meaning advice: “You know, my dear, you could benefit from a trip to the baths.” “Sarah, I have a wonderful doctor.” “You’re familiar with the Rest Cure, aren’t you, Miss Kaufman?”

If she interpreted such remarks correctly, time not only had caught up with her, but was threatening to pass her by.

As she examined herself now, however, she observed a slight improvement. She never might be quite the same, but she had regained most of the weight she lost last year; at five foot six still thin, but healthy-looking at one hundred and twenty pounds. The angles of her heart-shaped face had softened, her olive skin had lost its sallowness, and the velvety quality of her deep-set dark eyes had returned. She held out her hands. Still perfectly average in length and width, still squarish in shape with a deep nail bed. The only change was on the underside of her right ring finger. The callous had grown from a small ridge to a thick bump, the result of metal continuously pressing against flesh. It drove her sister, Tillie, crazy, the way she incessantly twirled her rings, counting each turn just under her breath. But something about the motion comforted Sarah, a simple way to feel pacified and protected. Mismatched and awkwardly stacked, the rings glistened under the bathroom’s soft white light. Her mother’s thin cluster of marcasites, the gold encircled garnet Obee had given her for her birthday, and the plain silver band, a place holder for the one she used to think would someday permanently grace her other hand.

She moved closer to the mirror. Perhaps a few more lines were etched on her forehead. And there definitely was more grey scattered throughout her chestnut hair, especially at the base of her widow’s peak, which became more obvious as she pinned it up into its usual French twist. But such minor alterations were a small price to pay. Not bad, she thought, as she straightened her pink silk chemise . . . all things considered. And with that, she swung open the door. Suddenly she was ravenous.

•••

Although it was noon, a few tables were still unoccupied. The dining car retained some of the luxury of the older trains: brass lamps, leaded glass windows, plush, thickly cushioned chairs. A uniformed Negro waiter escorted her to a white-clothed table midway down the isle. “Coffee or tea?” the man asked, as he placed a starched napkin on her lap.

“Tea, I think. Thank you.”

“Chicken consommé or Roquefort salad?”

“Salad.”

He smiled and wrote down her order, glancing at her book enigmatically before turning to a beckoning customer. She briefly tried to decipher his expression, but then decided that some things were best left unknown. Soothed by the gentle motion of the train, the tinkling of glass and silver, the gamy, citrus aroma of duck a l’orange, she marked her page and gazed out the window to the summer haze. At such a dreamy vision, the past retreated, wound itself back on the reel, and was held once more in suspended animation.

2

When Sarah arrived in Knoxville, the air was warm, but still fresh from rain. Thunderstorms were the mainstay of summer afternoons in the South. As the day progressed, plump white clouds had gradually gathered into tall grey plumes, and the haze had thickened, turning the landscape into a shapeless mass. Only when a yellow-white flash of lightening periodically electrified the sky could she distinguish one hill from another.

Still, Sarah had mostly enjoyed the ride. Despite the fact that it was hot and steamy outside, she had the cozy feeling of being indoors on a winter’s day. Not until the young Mr. Jarvis inadvertently sent her reeling did she begin to feel the heat of the storm. But for her cousin’s sake, as well as her own, she had pushed the worries out of her mind and relished the remainder of her ride. Lunch had been satisfying, and with her appetite and nerves calmed, she had managed to make progress on her book. In between chapters, she had followed the storm’s trajectory, from the first relieved droplets to the torrential downpour that signaled the beginning of its end.

By the time the conductor announced their arrival, the sun was out, streaming onto the landing where Lena was waiting. She waved at Sarah with both hands high above her head, plaid bloomers billowing out around her narrow hips, black bobbed hair swaying in the heavy breeze.

“Sarah! Sarah!”

Sarah dropped her suitcase on the wooden landing and ran toward her cousin. The two hugged and cooed for several moments, then drew back to examine one another. It had been five years. Much too long. Sarah held onto Lena’s bare, narrow shoulders, eyeing her up and down. So small. Only five tiny feet. Five and a quarter as she knew Lena would be quick to correct her. At the most one hundred pounds. But what a package! And evidently, still possessing an acute eye for fashion. Those French pumps with their curved heels and cream-colored suede were up-to-the-minute, not like those worn by any academic type Sarah had ever seen. “Lena, you little smarty. I’ll bet your male students have a hard time concentrating.”

Lena’s raven eyes gleamed. “Look who’s talking,” she said, or rather “tauwkink,” her Philadelphia accent especially pronounced at the moment. “You look marvelous, Sarah. You always were the pretty one—if you’d just do something with that hair!”

They both giggled, Sarah in her soft pianissimo, Lena in her throaty pianoforte. Lena had wanted Sarah to bob her hair ever since the style became popular several years ago. Although Sarah repeatedly said she would sooner stroll nude through the center of town, her cousin had raised the topic so often that it had become something of a private joke.

Bob or not, Lena was not pretty in the conventional sense, even less so than Sarah. Though she too was blessed with a clear, olive complexion and was shapely in the right spots, her nose was curved like a hawk, her square teeth were undersized, and her lips, today painted candy-apple red, were wide and thin. “A real meiskite,” as she said of herself. Regardless, Lena possessed that certain something, an ineffable quality that cannot be broken down into parts. Charisma, magnetism, whatever one called it, it drew people in—men, especially.

“C’mon,” she said. “Let’s go get your suitcase. You must be exhausted. I’ve got a driver ready to take us home.”

The two locked arms and walked through the stately brick depot toward a waiting jalopy spewing mildly noxious fumes. Lena already had slid across the seat when Sarah heard her name being called. She turned around to find Mr. Jarvis running toward her, sweaty . . . again. “You left this,” he wheezed.

Her book. She shook her head. “My mind was clearly somewhere else. Thank you so much, Mr. Jarvis.”

“Paul.”

“Paul. Paul,” Sarah said, yanking Lena playfully out of the car, “this is my cousin, Lena Greenberg. Professor Greenberg.”

Lena extended her small hand. “Hello, Paul. You’ll have to forgive my cousin. She knows full well that as a mere woman I can’t actually claim that title, but it’s the thought that counts.”

Blood rushed to his cheeks as he stared at her awkwardly. “Yes, I’ve heard a bit about your work on the trip here,” he said. “It’s nice to meet you.” Sarah eased the tension by summarizing, as best she could, his ideas about Mrs. Stowe. But when Lena simply responded with a “hmm,” and suggested, rather abruptly, that they discuss the work at some future date, Sarah was stunned. It wasn’t like her to be so curt, let alone turn down an opportunity for debate.

Paul didn’t seem to notice, however. He ripped out a piece of paper from his notebook, scribbled his telephone number and handed it to her. “I’ll look forward immensely to talking with you. Safe trip,” he called out, and dashed away.

As they drove off, Sarah grabbed her cousin’s hand and asked if she was feeling well.

“Absolutely. I just wanted you all to myself.”

“Well, that didn’t stop you from taking Mr. Jarvis’ number. He’s a little young for you, isn’t he?” Sarah joked.

She smiled mischievously. “That depends. I can think of a few things for which he might be just right.”

And then they both laughed, laughed to the point of tears. Perhaps Lena was fine, after all. She certainly seemed okay now. And besides, Sarah was already having more fun than she’d had in months.

•••

By the time they reached the small town of Edenville, perspiration was clinging uncomfortably to her dress. Sarah fanned herself with her book, trying to remember the benefit to her pores. Their driver, an ambitious business student who got paid by the hour, suggested they take a brief ride through the school before heading to Lena’s rooms. To sweeten the deal, he offered to roll back the car’s flimsy top. Though heavy now, the air was fragrant with the sweet smell of honeysuckle and blew sufficiently to unstick Sarah’s dress from the small of her back. Dusk, falling in varying shades of blue and orange, found the campus empty, save the fireflies, their bright tails flickering like miniature beacons in a darkening sky.

“The school was started by a group of Presbyterian ministers,” Lena said, assuming the impromptu role of tour guide as they passed through the entrance. Engraved on a gold plaque next to the magisterial gate was the college’s founding date: 1819. “One of the first fifty small colleges in the country.”

Sarah counted ten four-story, red brick structures with arched, Gothic windows and white plantation-like columns bearing names of local heroes, former presidents and generous patrons. They drove past Preston, Simmons, and Jackson Halls. Thickly foliaged oak trees peppered the trim lawns on which each building stood equidistant, collectively framed by woods so dense that, at least from here, they were indistinguishable from the encroaching night. Forming a star-shape pattern, each hall led to the chapel, a high-domed, wooden edifice with colorful stained glass depicting the life of Christ. Like planets circling the sun, the chapel, with its towering oversized steeple was the fixed point around which mathematics, English, music and all the other disciplines turned.

“You can’t imagine how many here still view the church as the life-giving force,” Lena said. “The anchor. The final word. Without its watchful authority, they think we’ll all go spinning out of control.”

“I don’t know how you do it, Lena,” Sarah said. It’s hard enough being a Jew. Even at court, where the separation of church and state is enforced, I have to watch my back.”

“You know me. I just let them believe what they want and keep going my own way. Besides, my department is different. The zealots don’t worry about us much. We only teach fiction, after all. It’s science they keep their eye on.”

As they exited the campus Sarah yawned deeply, covering her mouth in a failed attempt to hide the exhaustion that had suddenly overtaken her. On their way to Lena’s, they passed through Main Street, an eight-block paved road with quaint stores on either side selling the staples of modern life. City Drug, Duke Dry Cleaning, Coleman Tires, Luke’s Sandwiches, the names blurred together until Lena gave her ribs a little nudge. She shook herself just in time to see a soft, blue light rhythmically flashing: Cohen’s. Cohen’s. Cohen’s.

“Don’t want you to miss the Jew store, my dear,” Lena said.

Sarah watched the light as it flickered and faded from view. She’d heard the moniker was common in the South, a reference to Jewish-run shops selling dry goods inexpensively to farmers, Negroes and anyone else short of cash. Still, it was disturbing.

“It’s not as bad as it sounds, though,” Lena said, no doubt seeing Sarah suddenly stiffen. Most people down here don’t know enough about the Jews to know the term is offensive. Their ignorance isn’t malicious.”

“Oh come on, Lena. You’re smarter than that. Inexpensive is a euphemism for cheap, and cheap for Jew.”

“Well, of course, I know that’s true in many places. But it’s more complicated in these parts. The Cohens are well-liked, and their store does a good business. The euphemism isn’t fully realized.”

“Maybe so,” Sarah said. “But I wonder if they would mind if we called, oh, I don’t know, those little religious shops popping up everywhere the ‘Goy’ stores.”

Lena laughed. “You’re right, of course. But we’re not going to solve that problem today. I know what you’ve been through, and you’ve cause to be wary. We all do. But remember what you told me. ‘Lena, I want nothing more than to relax my body and rest my mind.’”

Sarah squeezed Lena’s hand and smiled. “All right, all right. I suppose I’m overreacting. You certainly seem to be surviving. Thriving, even.”

Lena turned away for a moment and was silent. “Yes,” she replied, “I’m great.” But the tone in her voice said something else. Sarah touched her shoulder and Lena turned back, smiling, perhaps just a little too much. Had the last year made Sarah so nervous that now she was misjudging her own cousin? She needed to watch herself, reading into things this way. “So, Lena, where is your place, anyway?”

On cue, the driver turned down a tree-lined street and stopped in front of a white clapboard house with a wide, inviting porch. Lena pointed to an upstairs window. “Right there.”

•••

Lena occupied two spacious rooms in a Colonial-style house for faculty women. One was a bedroom, in which there were two comfortable-looking twin beds, a large walnut desk strewn with papers, and three windows, on which, thankfully, the lace curtains were lightly blowing. The other room served as living space. An overstuffed maroon couch, black leather chair, Art Deco lamp and ebony Victrola surrounded a worn Oriental rug. The remaining area, except for a small icebox in the corner, was filled with books. Packed in the built-in shelves, stacked in neat piles on the floor, tossed here and there. Lena ordered Sarah to sit down and then went to fetch a snack.

“I’m sorry things are a little untidy,” she said, her head in the icebox. “I had meant to clean up more, but things have been a bit . . .” she paused, “busy here the past few days.”

Sarah hadn’t even noticed. She had already kicked off her shoes and unrolled her stockings, and was rubbing her sticky feet on the floor. The silk had been hot and the hardwood was wonderfully cool. “Your place is lovely. Don’t give it a second thought. But what have you been so busy with?”

Lena walked over with a plate of sliced Georgia peaches, a wedge of Swiss cheese and a pitcher of iced tea, a drink that she claimed was a rite of passage in the South. She put the Brandenburg Concerto on the Victrola as Sarah took of a sip of the sugary drink. “Oh, um, nothing worth mentioning. You know, just work. What do you say we go to dinner in a few minutes? Meals are served downstairs.”

“Forget dinner,” Sarah said, leaning back like the worn-weary traveler she was. “This is all I want. Cheese and fruit. Bach and tea. Three-quarter time.” She didn’t feel even a need for the drop of “imported” whiskey she’d become accustomed to taking at night. Yes, she’d brought the flask with her, just in case. And yes, in doing so she was technically breaking the law, however destructive that law had proven to be. But her doctor, who ignored Volstead entirely, had given her orders.

“You sure you want nothing else to eat?”

“Positive. I think I’ll even put off a bath until tomorrow.”

And so she did. For the remainder of the evening, Sarah sat right where she was, talking, laughing and sipping tea to the strains of her favorite classical composer. With each note, another muscle relaxed. By the time the last chord was struck, she was ready for bed. “Good night, Lena,” she said rising.

“Good night, Sarah. Sleep well.”

3

Sarah’s eyes flickered open. The room was still—it couldn’t have been any later than one in the morning—and just a hint of moonlight washed the room in muted purple-grey. She pulled herself up on one elbow and felt a bead of sweat trickle down her arm and rest in the folds of her wrist. Her whole body was drenched. The sound that had jolted her out of her slumber came again, a soft knocking at the door, this time with a girl’s voice calling out in a desperate whisper, “Miss Greenberg, Miss Greenberg!” She peered at Lena to see if she had heard and saw that she was already wrapping herself in her robe. “What’s going on?” Sarah’s voice cracked.

“It’s nothing. Go back to sleep.”

Lena motioned to Sarah to stay where she was and went to the front door just outside the bedroom. It creaked open.

“Kathryn?”

“Oh, Miss Greenberg. Did you hear?”

“Yes, yes, my dear. Shhh . . .”

The girl started crying.

“Kathryn . . . shhh. It’ll be okay.” Sarah couldn’t make out any more. Just soft whispers now and the girl’s weeping.

After a few moments, Lena returned to the bedroom.

“Lena, what on earth?”

“I’ll be right back. Don’t worry, Sarah.” She slipped a dress over her head, grabbed her heels, and hurried out the door.

Unable to do anything else, Sarah sat on the bed and stared into the darkness. Maybe if she cooled off she would be able to go back to sleep. She got up, exchanged her moist, floor-length silk nightgown for a short, cotton slip and pulled all the windows wide open. It was hot, the curtains motionless. She sank back in bed, knowing she should have trusted her intuition. Something was wrong.

•••

Sleep came in fits and starts, a restless conclusion to what she earlier thought, as she eased under the soft cotton sheets, would be a peaceful eight hours. Instead she dreamt, as she often did, of the past. Nightmarish visions of white ghostly figures, then hands squeezing her throat. In reality, she’d escaped. But not in her dreams.

No telling how long she might have continued to toss and turn had the landlady not awakened her with breakfast. Never did Sarah think she’d be glad to see a complete stranger hovering over her. She smiled gratefully and took the tray. A feast by her toast and coffee standards. Fresh squeezed juice, scrambled eggs and syrup-laden grits. The round, flat-faced matron introduced herself as Nan and told her that tomorrow Sarah would have to come downstairs like everyone else. “I ain’t no slave,” she said.

Sarah thanked her, took a few bites, and went to fill the tub with cold water. By the time she bathed and dressed, she was ready for a shower. Of course, Toledo summers were humid, too. But nothing like this. If the experts were right, soon her pores would disappear altogether.

To stop her mind from racing—wondering where Lena was, what had happened, why that girl was crying and what it had to do with her cousin—she perused some of the titles squeezed together on one of the shelves. Hard Times, Madame Bovary, Daniel Deronda. An abundance of Victorian novels, French philosophy, Walden. The complete works of Edith Wharton. A thick volume entitled Literary Criticism. Better finish her own book first. She picked up the red, leather-bound work she’d left on the nightstand and started to read:

You ought to be ashamed, John! Poor, homeless, houseless creatures! It’s a shameful, wicked, abominable law, and I’ll break it, for one, the first time I get a chance; and I hope I shall have a chance, I do!

Sarah silently applauded Mary Bird for standing up to her senator husband, John. How could he, an Ohioan no less, have supported the Fugitive Slave Act? Both were fictional characters, of course, but Stowe based them on the actions of real people. Leave it to the women to put things straight.

An hour or so later, Sarah marked the page and watched as her cousin came in, shuffled to the edge of the bed and fell back. For several moments, she lay there, flat and still. Then, as if awakened by the mesmerist’s snap of the fingers, she turned over and shaking her head, looked at Sarah. “I need to tell you something.”

“So I gathered. Are you okay?”

“Yes, I’m all right, don’t worry about me. But, well, it’s unbelievable,” she said. “The day before you arrived, a colleague of mine . . .” She stopped and swallowed. “He was found in the woods. Shot dead.”

“My God! How did it happen?”

“The police think it was an accident, a hunting accident.”

“That’s horrible, Lena.”

“Horrible, and a waste,” she said, still shaking her head. “Such a brilliant man. And so beloved. He had just been appointed to chair my department, and we had even begun work on a paper together.”

“I’m so sorry. I’ve been worried about you since you left with that girl this morning. Who was she?”

“One of his students. One of mine, too. The news is starting to spread, I guess. She’d just learned of it and was terribly upset.”

Lena sat up and pulled off her shoes.

“Lena,” Sarah said, “maybe . . . maybe I should go home.”

“What?”

“I said, maybe . . .”

Lena widened her eyes. “I heard you.”

“But . . .”

“No! I knew you would say that, which is precisely why I didn’t want to tell you. I may be needed here for a couple of days to help sort things out, but after that everything will go as planned. Beginning with our hike in the Smokies.”

“Maybe they’ll ask you to take his place.”

“Hardly.”

“Still, you’ll probably need to—”

“Not another word. I order you to stay! This is sad, very sad, but life will go on.”

Sarah sighed and smiled uncomfortably. “Okay. But if you change your mind—”

“I won’t.”

In fact, there was a part of Sarah that desperately wanted to go. To flee as quickly as possible. It was selfish, but she had come here to enjoy herself, to escape the unpredictable facts of life. After all, it only had been six months. She deserved a respite. But of course that was unrealistic. Life was full of the unpredictable. A vacation offered no immunity. Thankfully, it didn’t involve someone she knew. She sighed and relaxed her tight shoulders. Lena was right. Surely it wouldn’t take that long to do whatever needed to be done. Lena wasn’t a relative or even a close friend of the poor man. In the meantime, she could look around, explore the town. She glanced at her cousin, who had stretched out on the bed. Her eyes were closed.

“Sarah, I think I need a short nap.”

“Of course.”

“I can trust you not to hop on a train, can’t I?” she said, peering out from one eye.

Sarah smirked. “I suppose. Maybe I’ll take a walk into town.”

“Good idea.” She turned on her side. “That’ll take you about an hour,” she said groggily. “Timing wise, that should be just about right.”

Sarah put on the coolest outfit she could find. She didn’t go in much for hats, despite their popularity, but today she needed protection. From the two she brought, she grabbed the beige canvas one with the extra wide brim and left quietly. Lena was already fast asleep.

•••

Despite her light clothing, the humidity weighed Sarah down, forcing her to slow her usual rapid pace to an amble. It smelled different here. Rich, thick, fruity. Earthier than Toledo. Nevertheless, the fragrance was familiar. Not quite as sweet perhaps, but familiar just the same. It was in Nashville, 1918, the only other time she’d been in Tennessee. As chair of the Toledo branch of the League of Women Voters, she had attended the suffrage ratification conference there, held at the palatial Hermitage Hotel. She could still see vividly the walnut paneled conference room, inlaid marble walls and strangely intricate, stained glass ceiling: images of Madonnas and harpies, gods and devils. She remembered too, the roses everyone wore: yellow for suffrage, red against. “A fragrant sea of yellow and red,” as one reporter put it. Having worked tirelessly on this issue—even speaking to President Wilson at one point—Sarah naturally was elated when yellow prevailed, and even now she couldn’t help but smile a little in satisfaction.

She walked down two blocks, past a mix of Victorian and Colonial dwellings, all situated amidst foliage so lush there was no need for fences. When she reached the intersection, she turned left. On one side of the road was the college, on the other the courthouse, a smaller version of her own, granite and marble with Grecian columns. Up a long hill, and there was Main Street. In the daylight it looked smaller, less quaint, more provincial. She strolled past a shoe repair shop, a rustic, pre-industrial looking little place with a Gepettoish cobbler hammering away at a tall leather boot. Immediately next door was a dingy but crowded diner with a sign announcing the daily special: fried chicken, greens and “Joe’s” peach cobbler, seventy-five cents. And then, up ahead, Cohen’s. The Jew Store. She was curious, to say the least, and soon found herself peeking in its sparkling front window where thread, needles, shoes, work clothes and toys were all displayed in perfect order. Soon she realized that while she was looking in, someone was looking out at her, too. She raised her eyes and encountered a smiling face and a hand motioning her in.

“Well, hi there ma’am. What can I do ya for?”

The accent was strange. An unlikely coupling of West Brooklyn and East Tennessee.

“Oh, I’m just browsing.”

The man eyed her and nodded. He was at least two inches shorter than Sarah, with a thick crop of graying hair, pale blue eyes and a warm, full-faced smile. A Jewish smile, Sarah thought to herself.

“Well, y’all take ya time.”

The man kept looking at her, though, as if in recognition. “You’re not from these parts, are ya?”

“No, I’m from Ohio.”

“Well, I’m Charlie Cohen, and it’s good to have you here, dahling,” his accent suddenly favoring the Brooklyn half. “What is it that brings you to our fair town?”

“I’m visiting my cousin. She teaches at the college.”

“Oh. That right? What’s her name?”

“Lena. Lena Greenberg.”

“Ah,” he said nodding, smiling even more broadly. A second later, though, a shadow crossed over his face. “The college. Oh my. You must have heard about the death of that professor.”

Sarah sighed deeply. “Yes, I just found out.”

He shook his head. “Terrible. Did your cousin know him well?”

“Not well, but they did work together.”

He sucked air through his teeth and kept shaking his head. “Such a shame.”

“Shame my ass.” A heavy-set man with worn overalls and a leathery face walked over holding a small shovel he had just picked out. “That there’s a tragedy. Man was a true Southerner. Too few of ‘em these days.”

Sarah, feeling suddenly uncomfortable, gave a little smile and walked down the narrow isles. Toward the back of the store, she stopped to examine a paisley wool scarf, similar to one her mother had owned. The same swirling pattern and soft feel. It would be perfect with her grey winter suit. She couldn’t find a price tag, so she started back to the counter, where Charlie was nodding, his smile tighter, more reserved.

Clearly, the disgruntled customer had not been satisfied to let the conversation end, and indeed seemed to be fueling his own fire the longer he talked. “That professor, he was the kind gonna bring back the Confederacy. That’s what I heard. Gonna show ‘em this ain’t no lost cause. Those good for nothin’—” He picked up a plaid fleece blanket. “How much, Cohen?”

“How much can you afford, Mr. Sloan?”

The man didn’t answer. Fingering the blanket, he eyed the upstairs of the store, where a sign read: Negro Dressing Room. “Hey, anyone up there,” he shouted. Receiving no response, he yelled louder, undoubtedly aware that the room was occupied.

At that, a black teenage boy stuck his curly head out of the dressing room. “Yes, sir?” he said.

The man just glared, so the boy shut the curtain. Either he was drunk or just itching for a fight, mad at himself or the world. Whichever, he started for the stairs. But his wife, standing quietly until now, grabbed his arm, causing him to trip and knock over a neat row of fishing rods. Charlie walked over calmly and picked them up. “Now, now,” he said. “Let’s not start anything. He’s just a boy.”

The man shook him off. “I don’t need no kike tellin’ me what to do!”

“Bobby, c’mon. Let’s go,” his wife calmly pleaded. “The kids are in the wagon.” He shook her off. “And I don’t need no bitch bossin’ me around neither!” He stuck the blanket under his arm, threw two dollars on the counter and stormed out. Giving a slight nod to Mr. Cohen, his wife followed.

Charlie shrugged his shoulders and looked at Sarah, who was standing in stunned silence. This wasn’t quite the harmonious picture Lena had painted for her.

“Don’t let it bother you, ma’am,” he said. “No point.”

4

For once, the guidebook had not exaggerated. The Great Smoky Mountains were indeed “nature at its most sublime.” Sublime and gloriously indifferent. Away from the noise and crime, away from the lingering curious stares of her neighbors and friends—each waiting to see if she might yet break. Away from it all, and now, protected in a thicket of pines, she realized how grateful she was that Lena had encouraged her to stay . . . if hiding her suitcase could be considered a form of encouragement. Sarah couldn’t blame her, though, for resorting to such extreme measures. Had the bag been at her disposal she probably would have left. The professor’s death had already put her on edge, and the run-in at Cohen’s had proved more than she felt she could handle. But now, trudging up the dusty trail, dressed in overalls that sagged in all the wrong places, she felt better. Looking at Lena in the same silly outfit, she felt almost giddy.

They had decided to start with a hike up to Hotel Le Conte for breakfast. Sarah, whose stomach had been talking to her for an hour, was just about to ask Lena how much longer it would be until they arrived, when she spotted a pointed tin roof. Rustic, isolated, with an unobstructed view of seven-thousand-foot Mount Le Conte, the place, Lena said, was a well-kept little secret. A two-story frame building situated near a clear, stony river, the remote outpost complemented the rugged land in both design and scale. Their other option was the Allegheny Springs, but with its velvet-upholstered furniture, crystal chandeliers and imported French coffee, they decided it was too opulent, not at all in keeping with the spirit of the wilderness. Besides, they couldn’t have shown up there with sweat trickling down their foreheads and dirt clinging to their hems.

Once inside, Sarah, unwilling to let go of the view, peered back out again through the large, rectangular window in the entrance to the dining room. Had a blue jay not just splattered a white dropping as it flew by, she very well might have reached for the billowy cluster of pastel wild flowers dancing amidst the pines—it was that transparent. As they waited to be seated, she entertained herself by speculating on the quantity of vinegar required to attain such an effect—a quart, a gallon?—and made a mental note that she must get around to cleaning her own windows upon returning home, though the view outside of her little house on Fulton was not so grand.

She opened up her guidebook again and read a passage to Lena as they waited to be seated: “The Great Smokies are the western segment of the high Appalachian Mountains, majestically shaping the land from Asheville, North Carolina, to Knoxville, Tennessee, arguably some of the most spectacular scenery in the world. Wildlife that would stun the most jaded naturalist, slopes to both soothe the weak and challenge the hearty, flora of infinite variety. With each rise in elevation a dazzling explosion of color, shape and texture—purple-pink blossomed rhododendron, mountain laurel, red spruce, hemlock, silver bell, black cherry, buckeye, yellow birch. Towering pines. Chestnut trees reaching seventy to one hundred feet, softly blanketed in the region’s characteristic haze.”

“Right on the money,” Lena said.

Yep. It was all here, Sarah thought. Right there, on the other side of the vinegar divide.

She read on. “To preserve the region for future generations, efforts are currently underway to turn the region into a national park. Logging is threatening to destroy the last remaining sizable area of southern primeval hardwood forest in the United States and leave world-weary city dwellers one less pristine habitat in which to rejuvenate.” Sarah nodded in agreement at no one in particular. She was all for the park. Especially since it was a fellow Ohioan, Dr. Chase Ambler, who had started the organization that would bring it to fruition. But she was somewhat guiltily relieved that the area was not recognized yet as such, knowing that as soon as the official designation came, the crowds were sure to follow. Although in the last few years visitors to the region had increased dramatically, one could still travel for miles without encountering a soul.

•••

Only two of the eight tables in the dining area, a bright, surprisingly homey space with wood plank floors, red checkered tablecloths and bunches of wild geraniums, situated to take full advantage of the view, were occupied when they made their entrance. Seated at one of them was an overgrown Dutch family of five who had just received their food and were arguing in their guttural idiom about who had ordered what. Mr. J. W. Whaley, the owner and host, rearranged their plates until the brood was satisfied and then stretched out his arms and motioned for the cousins to come in.

“Mornin’, ladies. Late risers, aren’t cha?”

“Actually, we woke up earlier than usual. We’ve come up from Edenville.”

Towering over Sarah in a red flannel shirt, rolled up sleeves, with veins bulging over thickly muscled arms, was a Paul Bunyan of a man. The advertisers of the Big Six would have loved him, although his high-pitched drawl counteracted the effect a bit. “Y’all must be hungry, then, from such a long walk,” he said with enthusiasm, as if they were the first customers he had ever served.

“Yes, we’re starved.”

“Well, then, you’ve come to the right place.”

Escorting them past the empty tables, Mr. Whaley seated them near another gleaming window, directly across from a young couple on their honeymoon. “Traveled all the way from Alabama to be married by Justice of the Peace Ephraim Ogle,” he whispered, “down ta Ogle’s general store in Gatlinburg. Ephraim’s gettin’ to be a popular fellow these days.”

From the scavenged look of their table, the honeymooners had worked up a good appetite, too. Sarah smiled at them congenially before turning her attention to a bulky, dark mass moving in the distance outside.

“They’s been a bunch of ‘em this mornin’,” the woman said in a syrupy sweet twang.

Sarah turned around and smiled again. “What’s that?”

“Baars. A whole family, cubs and everthang.”

“Really?”

“Yep. They’s lovely, don’t ya thank? But scary, too.”

“Well I definitely wouldn’t want to get too close. But from here they do look beautiful.”

“Plannin’ on goin’ to the top?” the woman asked.

“We’re not sure,” Sarah said.

“We neither.” She looked at her husband who was loosening the notch of his beaded belt and then back at them. “If ya don’t mind me asking, where’d you’ns get them work clothes?” They look very comfortable, raht for hikin’.”

“I ordered them from the Sears catalog,” Lena said quickly.

Sarah raised one brow at her cousin. She knew Lena had purchased them at Cohen’s.

“I was just admiring your husband’s belt, too,” Lena said, not meeting Sarah’s gaze. “I sure could use something to help keep these things from sliding off me.”

“Cost me two dollars for this heah belt,” the man said. Them injuns ain’t cheap but they sure do make some handsome things. The Cherokee—they’re everwhar round heah.”

“Well, I’ll keep that in mind. Enjoy your hike.”

She turned back to Sarah, and before Sarah could even form a word, simply said, “Leave it alone.”

“But . . .” Sarah stopped herself and started to giggle. “Injuns?” she whispered. It’s almost too funny to be offensive.”

“Then don’t let it be, Sarah. R and R, remember?”

Lena fixed her dark eyes on her. She obviously wasn’t going to budge until Sarah relented. “Right,” she said, returning to the comfortingly unaltered view.

Looking out into the miles of untainted forest, though, Sarah couldn’t help but wonder about the professor’s shooting in the college woods. She thought of what a lonely death that must have been with no one there to speak to or hold his hand as he slipped from this world to the next. Lena hadn’t spoken of him for a few days now, and Sarah didn’t want to remind her of something she was trying to forget. But she also wanted Lena to know she should feel free to talk about it without worrying Sarah was going to plan her escape again. “Lena,” she started, “you’ve been fairly mum on your colleague’s death. Would you rather not talk about it?”

“No, not at all. There’s just not much to tell. The memorial service is next week. Apparently, it’s not uncommon for hunters to shoot birds in those woods. They don’t know who was responsible yet. The person who shot him probably doesn’t even know himself.”

“Have you heard anything about who will take the professor’s place?”

“The former chair has agreed to take the job for another year. By then the good ‘ole boys will find a replacement.”

“What about his personal life. Was he married?”

“He was. His wife died a few years ago.”

“Children?”

“No. And that apparently was a sensitive topic. When I asked him about it one time he abruptly changed the subject. I found out later that he was sterile.” Sarah felt a familiar lump starting to form in her throat. “Well, at least he had a legitimate reason.”

“Now, Sarah. You know that’s been your choice.”

“I suppose. Anyway, what about that paper you two were working on together? What’s it about?”

“You really want to know?”

“Of course.”

Just then Whaley came by with a steaming, speckled blue pot of coffee. “Breakfast will be ready in a jiffy,” he said, filling their mugs.

“Better drink up lest you fall asleep right here at the table hearing about it,” Lena said.

Sarah stirred in two teaspoons of sugar and took a giant swig of the nutty brew. “I’ll try my best not to doze off. Go ahead.”

“Okay. To begin, how does one teach literature? That is the question the professor and I were trying to address.

“I thought you already knew how. Isn’t that why you were hired?”

Lena laughed. “I suppose you’re right. But like everything else, education is always changing. You know, some think the imagination is the bane of society, that fiction is the devil’s work. Others, like myself, believe it’s a source of truth. But as an academic discipline, it’s essentially been taught as another part of history, a way to teach a moral lesson, a reflection of the author’s time and place.”

“Uh huh,” Sarah said. “That’s pretty much what I was taught.”

“Me too. But a growing group of scholars have begun to think that the literary work should stand by itself, you know, viewed as art, judged on its own merits. The question is, how? To be taken seriously in academia, you’ve got to have a serious method. Otherwise, the whole thing becomes too subjective, simply a matter of opinion. Are you with me, so far?”

Sarah nodded. “I think so, but, well, I don’t mean to sound simplistic, but what about enjoyment? Isn’t that an important part of reading?”

“Definitely. And actually that’s part of the argument. Students of literature are too bogged down with the background. They aren’t encouraged to see the beauty of the language, the soul of the story. Professor Manhoff . . . Nick . . . was helping develop a method to do so, a nearly scientific method.”

“Beauty and science. Sounds somewhat contradictory.”

“Well, yes. It is, sort of. That’s why the work isn’t complete. It’s really just begun. Because the theory is only in the beginning stages, contradictions are inevitable. But Nick was on the forefront of change.” Lena heaved a deep sigh and shook her head. “It’s so sad. We were even planning to present my . . . his . . . our paper to the next MLA convention.”

“MLA?”

“Modern Languages Association. That’s where we scholars show each other how brilliant we are!”

“Ah! I see. Teaching literary types how to appreciate literature.”

“In a manner of speaking. To rigorously appreciate it. Anyway, as I said, we had just started, but he was looking for a way to bridge the gap.”

“Gap?”

“Between fact and value, investigation and appreciation, in a sense, to resolve the contradictions you spotted.”

“How?”

“By moving from the particular to the general. By examining closely each word, each sentence, each image. First the parts, then the whole. He wanted students to see, as he said, ‘beauty in the making.’ After that’s accomplished, and only after that, would he put the book back in history. He wanted the words to enlighten the context rather than the other way around.”

“Interesting.”

“And he used modern writers as his examples, too. Modern American writers.”

“Why emphasize American?”

“Well, there’s this idea that anything written after the Greeks isn’t worthy. Old is good, new bad. And therefore literature by Americans is really bad. De Tocqueville said we were a bunch of boors a half a century ago, and we took it to heart. Perhaps he was right. But since the War, you know, with patriotism on the rise, there’s been growing acceptance, an interest in homegrown writers. Nick planned to use Mark Twain for his paper, and he hoped I would do something by Edith Wharton. He even had a working title, ‘The History of Aesthetics, the Aesthetics of History in Two Modern American Writers.’ “

“Very clever. If I don’t think about it too much, I even might understand it. And he asked you to help him?”

“Uh huh. Basically. Seemed to have no problem with my being a woman . . . or a Jew” Lena said, winking at Sarah.

“It really sounds like such a great loss, Lena.”

“I know. And he was so loved by his students, became a real father figure to many of them. Even more than that. They hung on his every word. Worshipped him, I’d say.”

“So what now?”

“Well, I’ll try to finish the paper as best I can. Try to fulfill his goal of reading at the MLA. I, uh, thought that, um, maybe between our outings you could even help a little, if you don’t mind. He was a prolific writer, and it’s going to take me a long time to go through all of his notes.”

“I’d be glad to do whatever I can. You know Lena, it doesn’t sound as if his students were the only ones who were smitten with him. There wasn’t anything . . . more going on between you two, was there?”

“What? No! No, Sarah. I admired him, but not in that way.”

Just then Whaley appeared at the table, balancing two plates overflowing with griddlecakes browned to perfection, thick-cut ham, buttered toast and a fresh pot of coffee.

“Here you go. And there’s plenty more where this came from,” he said.

“Thank you, sir. We may take you up on that.”

Lena started immediately, picking up a piece of each item on her fork and devouring them all together. After a prolonged glance at her plate, Sarah started with the ham, cutting off a small piece and slowly raising her fork. With a silent apology to her parents who sooner would have been tortured than let any pork pass through their lips, she bit into the piece of dark, honey-basted meat, enjoying the perfect blend of sweetness and salt. Then a bite of bread. And a slice of griddlecake. For several minutes she and Lena ate contentedly, each employing her own gustatory method. In the end, though, they were cousins, demonstrating their kinship by fulfilling the family mandate to “clean your plate.”

5

The tightness in Sarah’s calves was pleasantly uncomfortable. It felt good to have used those muscles. Still, if she didn’t move her legs soon she was liable to become petrified in her crouched position, so she grabbed a thick folder from the bottom drawer, stood up and limped over to the table.

For her taste, the college was a bit too much like the courthouse, designed to announce the importance of the activity for which it was built. Dark wood, marble floors, high domed ceilings framed with intricate molding. Imposing, sober, enlightened, the exact kind of environment she had taken a vacation to escape. Not to mention that the tiny file room to which she had been relegated was smaller and even narrower than her office. With no window, it felt both claustrophobic and stiflingly hot. But she was happy to help Lena. It was just for the afternoon, anyway. Tomorrow they were returning to the Smokies—she just hoped her legs would be ready to carry her.

“History teaches us what men are; literature teaches us what they should be.” The name “Voltaire” was scrawled on the cover of the folder. Sarah agreed with the great French philosopher. She invariably felt more inspired by a good novel than a scrupulously footnoted account of some war. All she learned from history was that men were prone to violence. Nothing new there. But in, say, well Uncle Tom’s Cabin, she was learning about redemption, forgiveness, about the importance of seeing beneath the surface of things. Of course, as Mr. Jarvis had said, Mrs. Stowe had her limitations, and she did spark a war. But in her novel, love and justice seemed to be the animating forces. For that matter, even in the stories of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, to which Sarah was somewhat embarrassingly addicted, she found inspiration in the power of the human mind, in man’s ability to overcome fear and unravel seemingly unsolvable mysteries.

She looked at the quote again, at the bold printing, so full of life, trailing across the folder in a diagonal line. She then opened the folder and started thumbing through the mass of papers. Some notes, typed documents, some full-length treatises written in a meticulous, slightly backward-leaning hand. The first was titled “Interpretive Criticism.” Lena had asked her to look for anything that appeared to relate to the topic of her and the professor’s MLA paper. Better pull that one out. The next was a mimeographed essay by Joel Spingarn. Was this the same person who founded Harcourt Brace? She and Obee had worked with the man at the NAACP. Probably. Creative Criticism. “Works of art are unique acts of self-expression whose excellence must be judged by their own standards, without reference to ethics.” Yes, definitely include this one. A mimeographed quote by a Martin Wright Sampson from the Dial in 1895: “I condemn as an obsolete notion the habit of harping on the moral purposes of the poet or the novelist.” This too, Lena would want to see.

“Excuse me?” A wheat-haired, lithe young woman knocked quietly and stood halfway through the doorway. “Excuse me, but have you seen Miss Greenberg?”

“She should be back shortly. Can I help you? I’m Sarah, Miss Greenberg’s cousin.”

“Oh, hello.” Sarah recognized the voice. Calmer, lower-pitched now, but the same as the other night. “I’m Kathryn. Kathryn Prescott. Miss Greenberg asked me here to help.”

“Yes, she told me you’d be coming. Nice to meet you. I guess my cousin feels I need some supervision!”

Kathryn smiled, her cupid-like lips curling around small, childish looking teeth. “No, it’s not that. She said there’s a lot of material to go through.”

Kathryn’s mouth didn’t quite match the rest of her angular face, which, though attractive in a natural, farm girl sort of way, hinted at a maturity beyond her years. Sarah wasn’t quite sure what it was. Something in the set of her pale blue eyes. “Well, that’s true,” Sarah said. I guess you know what to look for?”

“Uh huh. Um, where is Miss Greenberg?”

“At the police station. She and a few others were called in to hear the coroner’s report. Just a formality, I imagine.”

The girl motioned to someone in the hall, then eased in the rest of the way. Quickly assuming her place in the doorway was a tall, hovering male figure holding himself back cautiously. “I hope you don’t mind,” Kathryn said, taking the man’s sinewy arm. “Jim’s a friend. He was a student of Professor Manhoff’s, too. I think it would be okay with Miss Greenberg.”

A pleasant-looking fellow, Sarah thought. Straight, slicked back auburn hair, freckled up-turned nose, wide, open face. Average, in a good sense of the term.

“It’ll be a bit tight,” Sarah said, “but the more the merrier. We’ll need another chair.”

“Leave that to me, ma’am,” Jim said, smiling, and returned quickly with the required seating. He put down the chair and rubbed his palm on his trousers before extending his hand. “Nice to meet you,” he said.

“You, too.”

“Sad occasion though,” he added.

“Yes, I’m so sorry for you both, for the whole college.”

“Jim’s in the economics department, Miss Kaufman,” Kathryn said, resting her hand on his shoulder maternally, “but he told me he’s never enjoyed a class more than the one he took with Professor Manhoff. So many of us here felt the same way about him.”

“Well,” Sarah said, “at least you’ll be helping to further his work. How about I divide this stuff into thirds?”

They each took their share and began poring over his notes. After almost an hour, Sarah needed a break. The heat was overwhelming, and sifting through the piles of papers was a bit too reminiscent of the newspaper clippings she had searched through not so long ago for clues, anything that might help Obee. She got up and offered to get everyone something to drink, which the two were apparently craving, as both responded with an emphatic nod; Jim, in particular, who put his hand up to his throat in an exaggerated pantomime of thirst. Sarah clicked her way down the hall to the faculty rest area where pitchers and cups were kept. She filled the pitcher with water from a rusty faucet, grabbed the cups and walked back.

“Thanks,” Kathryn said. “Sit down, and I’ll pour.”

Sarah repositioned her wire-framed reading glasses and glanced at the students. Were they sweethearts? They were sitting very close. Whatever the relationship between these two, though, they were doing a great job. Their pile at least equaled hers. Lena would be excited to have so much to work with.

Sarah took a sip of water and thumbed through the remaining few papers. She was becoming accustomed to the terminology as well as to the professor’s verbose style, which is why the last item gave her pause. Short. Terse. Fragmentary. Just the opposite. She pulled out the hand-written sheet and squinted, as if her glasses had suddenly lost their potency, and read the first line. “Meeting with Mencken, four-thirty p.m. July tenth, Morgan home—Dayton.” She read it again. Mencken. The Mencken? Dayton—Dayton, Tennessee, she assumed. That’s where the John Scopes trial was being held, and as everyone knew, the Sun was sending its famed reporter to cover it. Sarah had been made particularly aware of this fact. Mitchell Dobrinski, who had helped her so much with Obee, was covering the trial too, for the Blade. For weeks he could barely contain himself at the idea of meeting, as he repeatedly said, the “greatest journalist of all time.” Mitchell, she thought, giving her rings a few spins. She had tried to keep her distance, but he was such a persistent fellow.

Anyway, Sarah knew Mencken was brilliant, but she didn’t quite view him as the second, or, more accurately for her, the first coming, as Mitchell did. The man had enemies for a reason. She did know, however, that in addition to being a famed newspaperman, he was a noted literary critic, and thus assumed that the professor’s meeting probably would have had something to do with books. That seemed to be confirmed by three names written directly underneath the reminder: Smart Set (the literary magazine that Mencken edited), Theodore Dreiser and Mark Twain. And then this quote: “A good critic is like an artist . . . So with criticism. Let us forget all the heavy effort to make a science of it; it is a fine art, or nothing.” By H. L. Yes, Sarah thought. Henry Louis Mencken. But below this were words, a list of some sort, which caused Sarah’s heart to skip a beat.

1. The Origin of Species—BY MEANS OF NATURAL SELECTION OR THE PRESERVATION OF FAVORED RACES IN THE STRUGGLE FOR LIFE.

2. George William Hunter—Civic Biology—Caucasian race—finally the highest type of all.

3. Nietzsche—A democracy of intelligence, of strength, of superior fitness . . . a new aristocracy of the laboratory, the study, and the shop.

4. Eugenics—the science of improving the human race by better heredity.

And scrawled across the bottom: Mencken = Natural Selection. All men are created UNequal. The strong will naturally prevail over their inferiors. Convince M. to publish and join the Brotherhood.

She removed her glasses, leaned back and massaged the bridge of her nose. How strange. Brotherhood. Usually a noble concept. But, the Brotherhood. That could be . . . that could mean . . . No, it didn’t make sense. Not at all given what she’d heard of the professor. Maybe these were notes for a novel. A work of fiction he was planning to discuss with Mr. Mencken. Convince M. to publish. That must be it. There was no other reasonable explanation.

Feeling satisfied with her conclusion, Sarah picked up her folder again, just as Lena walked in. Everyone looked up eagerly, but as soon as they saw her, their expressions changed. She was pale. And trembling, so much so that she had to steady herself against the table. Sarah started to get up.

“The coroner’s report is in,” Lena said.

Sarah glanced at the others then back at Lena.

“Nick’s death was not an accident.”

6

The lead bullet entered the head at too close a range for it to be a hunter’s—or anyone else’s—mistake. The slug came from a six point thirty-five millimeter, a pocket pistol. ‘Probably a Beretta.’ So says County Coroner, Foster McClean.

Sarah put down her copy of the Edenville Times. This changed everything, of course. Ever since she arrived, it seemed fate was sending her a message. Go home, Sarah. You’re not tough enough for Dixie. Go home. But now, Lena didn’t just want her to stay, she needed her to. Her cousin’s usual air of imperviousness had given way to vulnerability, even a bit of fear. Murder? That was only in books, a literary device, an imaginative way to make a theoretical point. The reality of it confused her. The proximity put her normally calm nerves on edge.

Sarah had never had children, hoping to find a man to marry first. But she suddenly experienced something like a mother’s protective instinct. An instinct lying dormant, waiting to be ignited, allowing her to keep her own demons—which, at the very mention of murder, surely would have otherwise risen to haunt her—at bay. Lena needed her support now. The kind of support that comes only with the bonds of blood. And so she would stay, at least for a while.

•••

Now that the professor’s death had been deemed a homicide, the town took on an entirely different aspect, as if suddenly electrified, as if an especially powerful bolt of lightening had hit one of their shady old trees. Sparks flew everywhere, a high voltage mix of gossip, fear and excitement.

During the next week, all the available university staff was questioned and dismissed, as were the students, who frequently came away from their interviews in tears. Of course, many were gone for the summer, a source of aggravation for the authorities. Perhaps the murderer escaped, was already out of the country. If a clue didn’t surface soon, they would have to broaden their search.

Lena’s interview was conducted in the downstairs parlor. When she and Sarah entered the sweltering, fussy room, they were met by two uniformed officers gulping tall glasses of iced tea; a young, slender, redhead and a pot-bellied, crusty old codger with droplets of sweat threatening to drip from his deeply creviced forehead onto his vein-ridden, bulbous nose. The latter, clearly in charge, reluctantly allowed Sarah to remain in the room. “I’m Officer Perry,” he said, “this heah’s Officer Briggs. He’ll be takin’ some notes, if y’all don’t mind.”

Lena turned to Sarah, raising her eyebrows, as if to question whether this was appropriate. Sarah nodded, and the interview got underway.

“So, Miss . . . Miss Greenberg,” Officer Perry said, glancing at a list of names, “when was the last time you saw the professor?”

The man’s grey, filmy eyes were accentuated by a florid complexion. Probably due to having arrested so many bootleggers, Sarah thought. After all, one occasionally needed to test the evidence, just to make sure. Near his chair, a dull brass spittoon awaited the detritus of the weed-like substance he dug out of a burlap pouch.

“The day before his body was discovered.”

“Under what circumstances?”

“We had been working on a project together.”

“What sort of project?”

Lena took a deep breath and exhaled. “A paper.”

“‘Bout what?”

“About the direction the teaching of literature should take.”

He rubbed his nearly non-existent chin. “How do y’all teach literature, anyway? Don’t you just read it?”

Lena tried to smile. “That’s an important first step, of course.”

Having finished the tea, Officer Perry now placed a wad of tobacco deep in his cheek, and then pressed the cold glass against his forehead. That gave his partner an opportunity to break in. Mild-mannered and well spoken, he had no detectable accent. “Tell me, ma’am. Do you know any reason why the professor might have been killed? Anyone who’d want to do him harm?”

Lena shook her head. “No. Absolutely not.”

Sarah took Lena’s hand. It was cold and clammy. The notes, she thought. She hadn’t stopped thinking about them, but for some reason hadn’t told her cousin. Why? She had started to, and then . . .

“Do you, ma’am?” He was staring at Sarah. He had been watching her.

“Of course she doesn’t,” Lena said, shaking her hand free. “My cousin’s just here for a visit. She arrived the day after Nick was found.”

He kept his gazed fixed on Sarah. “Ma’am?”

“No, no I don’t,” Sarah said slowly. “Lena’s right . . . except . . .”

Officer Perry leaned to the side, politely covered his mouth, and spit. A direct hit.

“Except?”

Lena turned toward her abruptly. “Except? Except what?” she asked, her face scrunched like an overly tight frock.