Читать книгу Radical Inclusion - Ori Brafman - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

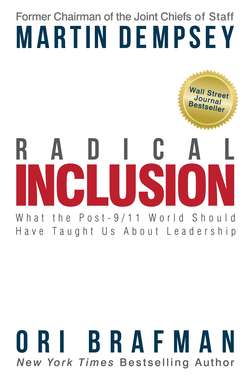

The Resolute Desk

ОглавлениеPresidential administrations have come and gone, but the same desk—crafted from the timbers of the British ship HMS Resolute and gifted by Queen Victoria to President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1880—has remained a fixture of the Oval Office since the days of JFK.

Kennedy sat at the Resolute desk when he deliberated how to deal with the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, and it was at that desk that he famously authorized the embargo of Cuba; it was at the same desk in 1987 that Ronald Reagan negotiated the terms of a nuclear disarmament deal with Russia.

It was there, in 2013, that President Obama faced an issue no less challenging than the ones JFK and Reagan had to overcome.

Just a few days before that Tuesday afternoon in April 2013, spring announced itself with the full glory of the cherry blossoms in bloom. But now the mood in D.C., and in the country as a whole, had shifted dramatically.

It had been less than two hours since the terrorist attack at the Boston Marathon.

The president immediately assembled his closest national security advisers at a closed-door meeting.

As he waited for the president to enter the Oval Office, General Dempsey looked to his right at Chuck Hagel, the secretary of defense. Hagel was straightening his tie, and when he caught Dempsey’s look, he slowly shook his head and sighed heavily. National Security Advisor Susan Rice, on his left, buried her nose in her briefing book, poring over the intelligence reports she had recently received.

Every administration has its ups and downs, but the nine months leading up to that meeting in April had seen one vexing national security issue after another. Dempsey knew that there would be intense interest in determining the motivation behind this new attack on American soil.

He had received news of the bombing when his executive officer, Colonel John Novalis, interrupted his preparations for his testimony before Congress, scheduled for the next day. Novalis had just completed a tour of duty as commander of an attack aviation brigade in Afghanistan. He had been selected because he was combat tested, virtually unflappable, and an exceptional leader. Dempsey knew Novalis would interrupt him only with something important.

“Sir, there’s been an incident,” Novalis said.

From his executive officer’s demeanor Dempsey could tell that what he was working on would have to wait.

“There’s been an attack on the Boston Marathon,” Novalis continued, then explained as concisely and clearly as possible that there had been two explosions near the finish line of the Boston Marathon and that the attackers were still at large. The Joint Staff Intelligence Officer and Joint Staff Operations Officer were meeting and would come to him with their assessment in the next fifteen minutes.

While most of us will never bear the awesome responsibility of defending our nation’s security, many of us have been in a situation where the status quo is suddenly disrupted. Dempsey had been trained over a lifetime to respond to exactly these kinds of crises.

He knew that the secretary of defense and the president would soon summon their national security teams, and he must be prepared. Indeed, ninety minutes later he was in the Oval Office. The media was already speculating about whether the attack was a result of U.S. withdrawal from the Middle East and whether it represented a new, previously hidden threat to the country’s safety. All of that would play out over time. Right now Dempsey needed to assure the president that the military was engaged, ready, and vigilant.

A quiet moment passed before the Oval Office door swung open, admitting a clamor—a staff member in conversation with the head of the FBI, several phones ringing, interns talking in rapid succession.

President Obama entered the room, loosened his tie, and rolled up his sleeves. In less than two hours he would address the nation on live TV. He looked for a place to sit but instead headed straight to the Resolute desk, leaned on its corner, and directed his first question to Dempsey. “Marty, give us your perspective.”

Most of us haven’t spent a day in uniform, but from watching Hollywood movies it’s easy to assume the head of the U.S. military would be a hawk, constantly pushing for aggressive combat operations. In reality, however, in the past ten years Dempsey had learned much about both the capabilities and the limitations of military power.

Nevertheless, he had to lay out all the options for the president. He had been with the president in other crises and knew that what he valued in these situations was clarity and brevity.

“Mr. President,” Dempsey began, “military personnel are providing support to law enforcement officials in Massachusetts. As you know, the Massachusetts National Guard has mobilized several hundred troops. We’re coordinating closely with the Department of Homeland Security.

“The Global Response Force remains at its normal state of readiness. We will accelerate their readiness time lines,” he continued, explaining that key parts of the military were being placed on high alert. “There are several things I will recommend if we receive intelligence that indicates the attack was part of a larger coordinated campaign or if it is accompanied by an increase of hostile activity toward our interests overseas. These could include ordering Strategic Command to maneuver satellite coverage and Cyber Command to shift assets to reinforce the FBI and Department of Homeland Security. It’s too soon to tell for sure, but at this time it appears that the attack is an isolated event.”

Privately, though, Dempsey wondered whether intelligence would link the perpetrators of this attack to any particular terrorist group. And then he wondered if that really mattered anymore. He looked at the Resolute desk a few feet away and reflected on how many obstacles it had seen overcome, how many changes it had borne witness to during its time in the Oval Office. Over the next few weeks and months, it would become obvious that we were experiencing something transformative.

Unlike the perpetrators of previous terrorist acts in the United States, the Tsarnaev brothers never received in-person training—neither at a camp nor through a network. This is where the threads of our story converge in an interesting way. Could it be that in order to fully understand what happened in Boston—and, for that matter, what happened at the Berkeley Milo Yiannopoulos protests—we need to look at the world through a McVegan lens?

Exactly two years after the Boston Marathon bombings, Ori convened a meeting at Harvard Business School where he invited senior White House officials, entrepreneurs, members of the Islamic community, media strategists, and policy experts to discuss how we might prevent an attack like the one in Boston from happening again.

The group began by trying to understand how the Tsarnaev brothers were recruited to commit the terror acts in the first place. They weren’t part of a formal organization that gave them commands, nor were they even members of an underground network that hatched a September 11–style attack.

In fact, the successful war against such terror networks had parallels, in a weird way, to what happened with Berkeley Students for Animal Liberation.

Like BSAL, starved for members, the terror networks had turned to technology and to narratives to stay alive. Just as Ori created McVegan shirts and stickers, terror group members were posting their content online and hoping for the best.

In the past several years, more and more videos had been posted. And remember: top-ranked videos are by definition compelling and easy to mutate or, more specifically, regenerate. The narrative continued to mutate until the Tsarnaev brothers learned from that content and committed their act of terror.

In a very real way, the narrative had become the organization.

The Harvard group recognized that you couldn’t contain the narratives through conventional means. Eliminating them from one social media site was like playing Whack-a-Mole, as videos would pop up on another site almost instantaneously. Trying to debunk the message (and win the debate) only gave the videos more attention.

That same year, a Palestinian stabbed a bus driver in Tel Aviv and posted the act of terror online. The terrorist had no organizational affiliation, and the video wasn’t promoted by a group of people. Still, viewers were inspired to commit their own stabbings and post these new derivative videos online.

Of course, positive content can spread in the same way; think of the “It Gets Better” campaign. But just as after 9/11 we had to get our heads around the fact that a distributed network—lacking a leader and without infrastructure—was a force to be reckoned with, we now needed to start considering videos and other narrative-building content as their own entities.

This brings us back to UC Berkeley. What if the protesters were actually organized neither by centralized command-and-control organizations nor by distributed networks, but instead were led, actually led, by online videos?