Читать книгу Frozen in Time - Owen Beattie - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

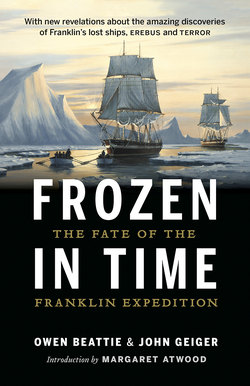

ОглавлениеForeword

THE EARLY HISTORY of European exploration in the Arctic was dominated by a single theme. Those who mimicked the ways of the native people—fur traders such as Alexander Mackenzie and Samuel Hearne—achieved great feats of discovery. Those who failed to do so—naval officers, for example, who viewed the quest for the Northwest Passage as but dangerous sport pitting British pluck against the elements—more often than not suffered terrible deaths.

Sir John Franklin, whose initial travels through the barren lands of Keewatin taught him a great deal about the ways of the Inuit, evidently failed to transfer such knowledge to his ill-fated Arctic command of 1845. Long after his own death on board the HMS Erebus in June of 1847, remains of his crewmembers were found far to the south, where they perished during a desperate quest for survival. Their shriveled remains were found in leather traces. They died dragging behind them an oak and iron sledge built in Manchester and weighing several hundred pounds. On it was a dory with all the personal effects of British naval officers, including silver dinner plates and even a copy of the novel The Vicar of Wakefield. Somehow they expected to haul this unwieldy load across the frozen wastes several hundred miles to possible rescue.

Not one of the 129 men who sailed with Franklin in 1845 survived. It was the greatest disaster in the history of Arctic exploration, and it gave rise to a mystery that would haunt the British for generations until finally the truth emerged in the wake of the events so powerfully chronicled in this elegant book. Frozen in Time is a story of mystery and adventure, an account of maritime sleuthing and discovery worthy of the pen of the great Victorian master of intrigue, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Like many great tragedies it begins in a sea of pride and blinding ambition.

The search for a polar route to Asia, which started during the reign of Elizabeth I with the voyages of Martin Frobisher, William Baffin, John Davis and Henry Hudson, had by the 19th century grown into an epic quest, a mission of redemption and destiny for a seafaring nation that, against all odds, had emerged triumphant from the Napoleonic Wars. For young officers in a peacetime navy—men such as Franklin, John Ross and William Edward Parry—the only route to advancement and promotion lay in exploration.

In 1818 the Admiralty dispatched two expeditions to the Arctic. Franklin went north, second in command of two ships with impossible orders to traverse the North Pole and descend upon the Beaufort Sea. John Ross and William Edward Parry went west into Baffin Bay and Lancaster Sound, the actual mouth of the passage. They sailed on until Ross discerned a range of mountains blocking the horizon, a ridge that no one but he could see. Returning to England, ridiculed for his folly, Ross yielded command of the second voyage to Parry, who in 1819 managed to sail all the way to Melville Sound, crossing the meridian of 110 degrees west, allowing him to lay claim to a prize of £5,000, a small fortune at the time. In a season of limited ice, the likes of which would not be known in the Arctic for decades, he came tantalizingly close to victory. Only the permanent pack ice of McClure Strait kept him from reaching the open waters of the Beaufort Sea. Parry’s experience led many to underestimate the enormity of the challenge. In the end his very success would lure scores of seamen to their deaths.

Even as Parry in 1819 made plans for a winter in the ice, Franklin set out overland from Hudson Bay to map the Arctic coast. Before he could explore he needed to learn to walk in snowy conditions unlike anything he had known. It took him three years just to reach the mouth of the Coppermine River. Soon after, with most of his men dead or dying and unable to move on, one started to grow healthier by the day. It turned out the man had killed two of his companions and cached their frozen corpses in the snow. Each day he hacked off chunks of meat, allowing him to grow plump as the others, including John Franklin, withered in the cold. When this was discovered, the culprit was summarily executed.

By the end of Franklin’s second expedition in the North in 1827, he had travelled thousands of miles on foot or by water, and the entire northern shore of the continent had been mapped, an astonishing achievement for which he would be knighted upon his return to London. Amid the fanfare he met and married Lady Jane, a proud and indefatigable woman who would make his destiny her own.

After nearly a decade as governor of Tasmania, Franklin came back to England at age fifty-nine, just as the British government was about to sanction the first expedition in seven years to search for a way through the polar ice. Despite his age, he managed to talk his way into the command of what promised to be the crowning achievement of his life. The two ships, Erebus and Terror, were completely refitted and equipped with the first screw steamers ever to be used in the Arctic. To man them, Franklin had the pick of the British Navy. It took three years before they were ready to sail, with every stage of the process, every technical innovation and each hour of training only increasing expectations and the certainty of success.

Sailing down the Thames on May 19, 1845, along riverbanks lined with thousands of well-wishers, Franklin readied his crews for a run across the sea, wind at their stern. His orders were to go where Parry had gone, and succeed where Parry had failed. They made for Lancaster Sound. Finding Barrow Strait blocked with ice, they went north, exploring Wellington Channel before returning south along Cornwallis Island to a winter anchorage at Beechey Island.

Come spring, with the way west still blocked by pack ice, they sailed south following an uncharted waterway along the west coast of North Somerset Island. Approaching King William Island, surrounded on both sides by open water, Franklin made a fateful decision, ordering his ships down the western side of the island, where they became beset in ice not twelve miles offshore. It was September. Through a long and harsh winter they drifted west of the mainland with the pack ice, even as men succumbed to tuberculosis, scurvy and madness brought on by lead poisoning. Half of the tinned rations had gone bad. Weakened by lack of food, poisoned by what little they had, men began to die.

In the spring, sledging parties went out, only to discover that had Franklin chosen the eastern side of the island they would have avoided the ice that trapped their ships, and quite possibly have reached the open waters of the Beaufort Sea, the very passage of their dreams. Demoralized, they returned to their ships, only to find their commander on his deathbed. Sir John Franklin, who died on June 11, 1847, mercifully did not live to witness the unbearable agonies of his men and their final descent into depravity.

Even as a third dark winter came upon them, the survivors found themselves still beset, their vessels some fifteen miles from shore. With the ice tightening as a vice, threatening to crush the hulls at any moment, they had no choice but to abandon the ships at the first sign of the return of the sun. Their only hope was to head south down King William Island, across Simpson Strait to the mainland of the continent, where if they could find their way to the mouth of Back River they might fight their way a hundred miles upriver to the nearest outpost of civilization.

They set out April 22, 1848, 105 survivors, all suffering from scurvy and starvation, each man responsible for a two hundred pound load, which he was expected to drag 250 miles (400 km). As the bedraggled caravan trudged south, it left in its wake a trail of detritus, castaway medicine chests and canvas tents, picks, shovels, blankets and bodies. A few survived the trek and managed to row to the mainland. Of these, one or two may have managed to drag themselves inland. But in the end all would perish.

The uncertain fate of the Franklin expedition dismayed the Admiralty and British government, even as it aroused the passions of a nation bound together by a mystic sense of patriotism. Lady Franklin, influential at court, shameless in her dealings with the newspapers, did all that was humanly possible to inflame public sentiments. In doing so, she effectively shifted the narrative from grotesque failure to epic saga of survival and hope. She alone ensured that her husband’s greatest achievement would be his disappearance, for it was the search for Franklin that heralded the greatest period of exploration in the history of the Arctic.

In the decade after his death, no fewer than forty major expeditions set out from Britain, some sponsored by the government, at least four by Lady Franklin herself. Six went overland to search the northern shores of the continent. Most went by sea, either through the Bering Strait on the chance that Franklin had reached the Beaufort Sea, or through Lancaster Sound, following his last known trajectory. Each extended its range by sending out sledging parties, some of which travelled as much as 300 miles (480 km) from their mother ships. With every journey, more and more of the Arctic became known, its waterways charted, the blank spots on the map filled.

As the months and years went by, and any hope of rescuing the men faded, the search shifted into an obsession with discovering their fate, and salvaging their remains for proper burial at home. Beginning in 1850, ships brought back bits and pieces of evidence, tin cans and compasses, a chronometer, scraps of cloth, several bibles. Formally exhibited as “Franklin Relics,” they took on almost religious significance.

Then, even as the search narrowed, unsettling news stunned the British public. In 1853 John Rae, exploring overland from the south, met Inuit who claimed to have encountered in the winter of 1849 forty white men heading south, dragging a sledge. They had been starving, and the Inuit traded a small seal for bits of metal. Later that season, the Inuit had come upon some thirty corpses on the mainland, another five on a nearby island, not far from the mouth of a large river. With this account in hand, Rae returned to England and claimed the £10,000 prize that Parliament had put up for the first to solve the Franklin mystery. He also brought back enticing evidence of a darker story. From the descriptions of the mutilated state of the bodies, and the reported contents of their kettles, there could be little doubt that Franklin’s men in their desperation had resorted to cannibalism.

The expedition had consumed a decade, only to yield a result that challenged all Victorian notions of moral certainty and superiority. As to the fate of Franklin himself and his ships, nothing whatsoever had been unveiled. If this was not enough to dampen enthusiasm for the search, the outbreak of war in Crimea most assuredly was. With thousands of British boys dying before the walls of Sebastopol, it became increasingly difficult to arouse sympathy for 129 officers and crew, gone for a decade and marred by their final acts in life, deeds that provoked only repulsion in the hearts and minds of their countrymen. In March 1854, the Admiralty officially declared that all of Franklin’s men were dead, and formally removed their names from the Navy List. There was only one dissenting voice, that of Lady Jane Franklin.

In July 1857, she sent out a final expedition, captained by Francis Leopold M’Clintock. Like so many others it became beset in sea ice, and after two years returned, with nothing but more disturbing news. Accounts of human bones scattered along the shores, two corpses found inside a dory along with forty pounds of chocolate, new stories from the Inuit of cannibalism and madness. Evidence not of imperial glory, but of complete cultural failure and betrayal by men who insisted on importing their environment with them, rather than adapting to a new one in which they found themselves struggling to survive.

For nearly two centuries the fate of Franklin’s ships remained unknown. Such was the allure of the mystery that their location, though never established, was registered as a Canadian national historic site. For years it was the only such maritime site that visitors could not visit, for it was nothing more than an abstract point on a map, delimited by a 200 yards (180 m) radius, an approximate place just west of King William Island where it was believed the ships went down. Like the Northwest Passage itself, the location lay only in the realm of dreams and the imagination.

Then came the astonishing discovery of Erebus, and later Terror, shadowy silhouettes lying in shallow waters, anchored if you will in geopolitical reality. Ottawa may call for the landmarks and all the surrounding waters to be designated UNESCO World Heritage Sites, if only to boost the nation’s claim that the Northwest Passage is an internal Canadian waterway, and not as the Americans and others claim, an international strait. At stake is the sovereignty of the Arctic, control of maritime traffic across the polar north, and with it ownership of the vast mineral and oil and gas resources waiting to be discovered. Thus the discoveries so elegantly described in this book have political implications that go far beyond this moment in time. In a manner he could never have envisioned, fully 170 years after his death Sir John Franklin remains very much a force to be reckoned with in the Arctic. Lady Franklin would be pleased.

Wade Davis