Читать книгу The Empire Reformed - Owen Stanwood - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

Catholics, Indians, and the Politics of Conspiracy

IN THE SUMMER of 1688 the governor of the Dominion of New England, Sir Edmund Andros, faced a political crisis. A group of hostile Indians had attacked the colony’s northern and western borders, killing and capturing a number of English settlers and causing frightened townspeople to take refuge in garrison houses. Even more alarming than the violence, however, were the colonists’ reactions. In Maine, local officials foolishly imprisoned several Abenaki chiefs, while the people of Marlborough, Massachusetts, assembled in arms without any instruction from the governor. To calm these fears, Andros sent his lieutenant, Francis Nicholson, on a good will tour of the New England backcountry. He assured the people, both English and Indian, that they were safe “under the protection of a greate King, who protects all his Subjects both in their lives and fortunes.” In the eyes of Andros and Nicholson, New Englanders’ hysterics made little sense. The Dominion of New England—a potent union of all the colonies from Maine to New Jersey under the command of an experienced officer—provided the best defense against external enemies that the region had ever possessed. The king and his redcoats, not a motley local militia, would keep the plantations safe.1

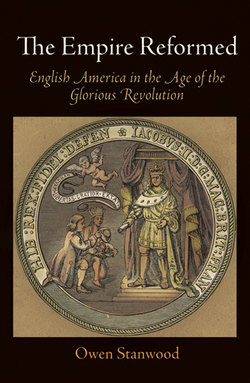

The crisis in the Dominion represented the first major setback in what had been a fairly successful example of imperial state building. The key to the Dominion was protection, represented perfectly in the new union’s official seal. The design featured James II, “Robed in His Royall Vestments and Crowned, with a Scepter in the Left hand, the Right hand being extended towards an English Man and an Indian both kneeling, the one presenting the Fruits of the Country and other a Scrole.” Above them a flying angel held a banner with the Dominion’s motto, “Nunquam libertas gratior extat,” “never does liberty appear in a more gracious form [than under a pious king].” The monarch received allegiance and tribute and provided protection, which was the key to political stability. Andros and his allies knew that the Dominion’s programs would excite opposition from New Englanders who defined both “liberty” and “piety” in very different ways from James II’s allies. However, they believed that they could keep control as long as they upheld their promise to provide protection—and they were mostly right. Despite some opposition, the Dominion did not fall until subjects began to believe that their leaders were not protecting them at all, and in fact aimed to subvert and destroy the country. The opposition to the Dominion grew as a result of its failed Indian policy; as native enemies attacked the borders, New Englanders turned against their leaders.2

Figure 4. Seal of the Dominion of New England, 1686. William Cullen Bryant and Sydney Howard Gay, A Popular History of the United States (New York, 1879), 3: 9.

The wave of fear that threatened the Dominion combined several different varieties of popular anxiety. Aside from the popish plot alarms that periodically struck both England and its colonies, settlers in North America also obsessively feared Indian attacks. Europeans and natives had experienced tensions since the newcomers arrived on the continent, but the violence increased during the 1670s. First, in 1675, a coalition of Indians under the Wampanoag sachem Metacom (King Philip) attacked English settlements in New England in response to land disputes and religious tensions, dramatically revealing the region’s vulnerability. The following year Indian attacks on the frontier of Virginia inspired a massive popular revolt against Governor William Berkeley by subjects, led by the upstart Nathaniel Bacon, who believed the governor was not protecting the colony from Indian enemies. While peace had returned to both places by 1677, the legacy of this unrest remained. As a result, the fears of popish plots that crossed the Atlantic after 1678 arrived in places already primed to expect the worst.3

Popular panics of the 1680s proved particularly powerful because they combined the tropes of antipopery with homegrown racial fears. Increasingly, people became apprehensive of a massive plot that combined papists and Indians into a gigantic, diabolical coalition that aimed to push English Protestants off the continent. This belief did not come naturally; indeed, during the first period of colonization many English settlers had expected that Indians would be natural allies against a common Catholic enemy that, according to the “Black Legend” of Spanish cruelty, had victimized both groups. In time, however, Protestants began to redefine natives as violent enemies who were particularly susceptible to the temptations of priestcraft. In making these arguments, colonists drew on another form of anti-Catholic rhetoric perfected in Ireland, where the “wild Irish” had proven impervious to Protestantism, and outsiders explained this religious intransigence by pointing to a lack of civility among Irish Catholics.4

By the time Andros faced his troubles in 1688, the identification of Indians and Catholics had become widespread. This development marked the Americanization of antipopery, the adaptation of a set of European fears to explain conditions on the colonial frontier. The results were dramatic and long lasting. On one hand, the wave of fear endangered the program for imperial reforms, giving a new opening to those Protestant radicals who believed that centralization was merely another branch in a popish plot. But at the same time, the common fears of a Catholic-Indian design gave colonists across the colonies a common political language, one that combined their desire for security, their Protestant heritage, and their nascent sense of racial privilege. Fear could tear the empire apart, but it could also put it back together again. The results of the crisis depended a great deal on how Andros and other imperial officials responded to popular fear.

• • •

The first reference to a Catholic-Indian conspiracy appeared, ironically enough, in the private correspondence of colonial America’s most prominent Catholic. Cecil Calvert, the second Lord Baltimore, founded the colony of Maryland in 1634: a bold experiment intended to demonstrate, among other things, that Roman Catholics could be loyal English subjects and work for the king’s interest. His plans for religious neutrality inspired opposition, however, and not just from Protestants. Members of the Society of Jesus, who had provided spiritual support for the first colonists and endeavored to convert local Indians, resent Baltimore’s refusal to grant them preferred status in what they considered a Catholic colony, even threatening at one point to have the proprietor excommunicated. This dispute led Calvert to suspect the Jesuits of more sinister designs, confiding in a letter to his resident governor that the priests intended to employ local Indians to destroy anyone who stood in the society’s way, including the Catholic proprietor. In Baltimore’s mind, the Jesuits used religion as a pretense to further their political goals—and they were not afraid to encourage violence if it brought them to power.5

It is a testament to the power of anti-Catholicism in seventeenth-century English thought that even a prominent Roman Catholic used antipopery to criticize his rivals. Indeed, it demonstrates the extent to which “popery” as a construction was detached from actual relations between Catholics and Protestants, or even among groups of Catholics and Protestants. Perhaps unconsciously, Baltimore drew on two strands of anti-Catholic thought, each of which became important in the colonies over the next half-century. First, he painted the Jesuits—hated agents of the counter-Reformation—as devious papal agents who would stop at nothing to accomplish their worldly ends. Second, he argued that the priests would employ impressionable, weak-minded foreigners—in this case Indians—to accomplish their goals. This aspect of antipopery also had a history in Europe, but it soon became even more important in the colonies, where foreigners were particularly strange and the Jesuits made great efforts to convert them.

In Protestant propaganda, Jesuits were the very worst of the papists. Founded by Ignatius Loyola in the 1520s, the order had gained a reputation as the strictest defender of Catholic orthodoxy during the counter-Reformation. Polemical Protestant diatribes against the society abounded in northern Europe during the 1600s, stressing several different sides of the Jesuit character. First and foremost, the Jesuits were defenders of papal authority and the foes of Protestant princes, and they would do anything to serve their master’s cause, even if they had to murder recalcitrant monarchs—as they did French king Henri IV in 1610. Beyond their ill intentions, the Jesuits were also master tricksters. They blended into their surroundings by dressing in disguises, speaking numerous languages, and using personal charms to insinuate themselves into Protestant society in order to undermine it. Both of these fears appeared in an English newspaper report from 1679, just after the revelations of the popish plot. The paper reported that a man in a London coffeehouse revealed himself to be a Jesuit in disguise, and when asked whether he endorsed “the Doctrine of Killing of Kings,” responded “That their Doctrine was to Kill every one that stood in their way.”6

Beyond being violent tricksters, Jesuits were also known for their skill in converting people to Catholicism. The priests themselves encouraged this reputation by publishing reports of their missionary successes in the Far East and America, and while these Relations served primarily to encourage support for the Jesuits in the Catholic world, they had the additional effect of confirming Protestant fears. Enemies of the order explained its success in much the same way modern historians do, by arguing that the Jesuits encouraged pagans to become Catholics by drawing on similarities between Christianity and paganism. In a fictional dialogue among three Jesuits published in 1689, for instance, a missionary to Siam bragged that he stressed the common points between Catholicism and the local religion, especially “Worship of Images” and “a blind tame submission to the Doctrines, Worship and Ceremonies of their false Religion, [which] makes them resemble our People absolutely.” If this tactic did not work, the missionary advocated changing the principles of Catholicism to suit local circumstances; for instance, he believed that by deifying the saints he could convince adherents of polytheistic eastern religions to embrace the faith. To Protestants, these reports—fabricated though they were—reinforced the Jesuits’ reputations as dissemblers and casuists who would lie without shame to advance their cause, and who had particular success with impressionable pagans. It also proved that their true goals were not religious, but worldly: they wanted power above all else, and would not let principles stand in their way.7

The picture of Jesuits in propaganda was exaggerated and in some respects entirely false, but it did bear at least a superficial resemblance to reality. Many Jesuits did pride themselves on their ability to win back “heretics” to the true faith, and especially in the English dominions the priests considered the reestablishment of Catholicism as a primary goal. The behavior of Maryland Jesuits helps to demonstrate why Protestants were afraid. Even without the establishment they desired, Maryland provided the priests a degree of freedom unknown in England or other colonies: they no longer needed to travel in disguise, and they could openly conduct worship services. As one prospective priest put it in a letter asking to be assigned to the new colony, “Where I live, I am abriged of liberty in doing the good I could wish, wch maks me more earnest to be els where imployed.” Besides ministering to Maryland’s small but influential Catholic population, the priests set out to create as many new Catholics as they could. This goal appeared clearly in a catechism from the mid-1670s that survives in the archives of the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus. Probably intended as a guide to young priests in proper doctrine, it attempted to combat the most fundamental Protestant teachings. It stated that the Church received its imprimatur from Christ himself, and therefore “we cannot call in question the truth of any one thing the Catholick Church teaches without making Christ a Lyar.” It also argued that scripture only contained part of the truth, and “we cannot tell wch is the true scripture from the false” without help from the church. In short, Maryland Jesuits traveled the countryside extolling with great zeal a message that directly refuted the most basic tenets of Protestantism. It is not surprising that many people took offense.8

Another story from the Jesuits’ own writings helps to illustrate the threat the order posed to Protestantism. From its earliest days, and especially after the 1640s, Maryland welcomed a large number of Reformed Protestants, many of whom migrated from the less tolerant Anglican colony of Virginia and settled near the Severn River in a community called, in typical Puritan fashion, Providence. These settlers saw the Jesuits as devious rivals who would do anything to convert heretics, as one episode made clear. In the late 1630s, according to a Jesuit report, a Protestant man fell ill from a snakebite. A local Jesuit endeavored to see the sick man, partly to treat him, but mainly to win his soul for the Church before he died. These deathbed conversions were particularly offensive to Protestants, who believed that Catholics took advantage of the mental and physical weakness preceding death to poach souls. In this case, a friend of the sick man stood guard to make sure the Jesuit could not gain access to the patient. “Nevertheless,” the report stated, “the priest kept on the watch for every opportunity of approach; and going at the dead of night, when he supposed the guard would be especially overcome by sleep, he contrived, without disturbing him, to pass in to the sick man; and, at his own desire, received him into the Church.” Despite appearing in a Jesuit letter, this story could have served as a potent piece of anti-Catholic propaganda, as it reinforced the belief that Jesuits used trickery and artifice to advance their cause.9

The Jesuits’ penchant for trickery made it critical for Protestants to resist the order in any way they could. Some colonies banned the presence of Jesuits, and even in places like Maryland where the priests could legally reside Protestants prided themselves on the ability to resist their advances. But even if all Protestants stayed true to the faith, the Jesuits posed a problem. As one tract explained, resistance to their designs only made the Jesuits more devious: “where they cannot convince,” it explained, “they labour to destroy.” They could succeed because of a network of foreign allies whose main ambition was to “massacre the whole Protestant Party” and clear the way “to build a corrupt Church.” In England opponents of the Jesuits believed that the order intended to invite the French or Spanish to invade the kingdom, but another tactic was to target inhabitants of foreign nations who did not have the training or intellect to resist Jesuit advances. This had particular relevance in America, where a large population of natives lived among the colonists, and where Jesuits had already begun to establish missions.10

In the 1640s, particularly in Maryland, English colonists began to worry about what would happen if the Jesuits insinuated themselves into Indian communities. They had a useful precedent from Ireland, another part of the empire where Jesuits and other popish priests had labored, with astonishing success, to infiltrate a population of common people most English considered impressionable and uncivilized. The lessons from Ireland could not have been encouraging. Despite the expectations of reformers in the sixteenth century, the “wild Irish” clung tenaciously to the Catholic faith, and Protestant observers tended to blame two factors: the depraved state of the populace and the underhanded methods of the clerics. Moreover, the priests’ successes had dire consequences for Ireland’s Protestant minority, as the Irish peasantry became willing shock troops for the Catholic cause.11

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 was an epochal event in the history of British anti-Catholicism. Before this time, antipopery had been a less potent force in Ireland than elsewhere, mainly because the vast numbers and diversity of the Catholic population forced Protestants to accept that the true face of Catholicism was more complex than their conspiratorial logic suggested. The events of October 1641, when Irish Catholics rose up in a bloody rebellion against English Protestant rule, immediately prompted Irish Protestants to place their own struggles within a global context. More important, the reports of “popish” atrocities in the rebellion quickly spread to England and beyond, becoming an important source of propaganda as the nation moved toward civil war.12

This propaganda—as popular in the 1680s as in the 1640s—provided a salient example of how uncivilized people could aid the popish cause. Protestant writers targeted the usual shibboleths of antipopery: Jesuit priests; infiltrators from foreign countries, especially Spain and France; and unscrupulous “evil counselors” who pretended to be Protestants but really promoted popery. None of these masterminds could have succeeded without “the blind, ignorant, and superstitious people,” who “rise up and execute whatever they command.” In addition, the wild Irish served as the agents of popish cruelty: according to one propagandist, “they acted with that brutish fury, as if the wild Beasts of the Deserts, Wolves, Bears and Tigres, nay Fiends and Furies had been let loose from Hell upon the Land.” Not even unborn children were safe, as “their Hellish Rage and Fury extended also to the Babes unborn, ripping them out of their Mothers Womb, and destroying those Innocent Creatures, to glut their Savage Inhumanity.” In this reading of the rebellion, the Jesuits were the masterminds, but the wild Irish provided the savage violence that brought the rebellion to its terrible conclusion. It would not be difficult to imagine a similar scenario in America, and in time colonial witnesses would describe native attacks using almost identical language.13

Nonetheless, there was no reason to assume that Indians would naturally fall into the role of the Irish. Early colonization tracts usually expressed optimism that the Indians would gravitate toward alliance with the English, especially when they recognized the contrast between good Protestants and cruel, rapacious Spaniards. In the logic of antipopery, moreover, pagans usually occupied a step above papists. The English poet and politician Andrew Marvell wrote that “The Pagans are excusable by their natural darkness, without revelation,” while “the Pope avowing Christianity by profession, doth in doctrine and practice renonce it.” From the 1640s, therefore, a few colonists had good evidence to suspect that Indians could be auxiliaries in a Catholic cause, but such beliefs were not widespread.14

Not surprisingly, Maryland’s political situation provided the most fertile ground for fear that Indians could fall to the temptations of popery. Founded by Catholics, the colony nonetheless welcomed a large number of Protestant dissenters, drawn to the colony by Lord Baltimore’s generous policy of religious toleration. Proprietary authorities understood that they ruled over a powder keg, where religious passions could explode into violence at any time; they attempted to avoid such a scenario by restricting religious speech. Accordingly, the 1649 “Act concerning toleration” including a long list of outlawed religious slurs: calling your neighbor a “Jesuited Papist” or a “schismatick” could result in a ten-shilling fine.15

On the whole, these attempts to promote religious understanding failed. During the turbulent Civil War years of the 1640s and 1650s, when rumors of Catholic plotting reached fever pitch in Britain, Protestants in Maryland rejected Lord Baltimore’s authority in large numbers, mounting two successful rebellions. Only through impressive maneuvering in London—and an improbable alliance with Oliver Cromwell—did Baltimore manage to hold onto his colony.16

In the meantime, the proprietor’s opponents barraged him with a number of charges. One tract claimed that Baltimore’s intention was to create a “receptacle for Papists, and Priests, and Jesuits,” and that he even intended to bring 2000 Irish to the colony who “would not leave a Bible in Maryland”—surely an alarming prospect only a decade after the 1641 rebellion. Colonial agent Leonard Strong was even more blunt when he described the series of events that led a cadre of Protestants to throw off the lord’s authority, claiming that Baltimore required subjects in Maryland to “countenance and uphold Antichrist,” meaning the Catholic church, and he was willing to use tyrannical force to ensure submission. This force extended even to employing Indians. When proprietary forces faced off against Protestant dissidents in the “Battle of the Severn” in 1655, according to Strong, “the Indians were resolved in themselves, or set on by the popish faction, or rather both together to fall upon us: as indeed after the fight they did, besetting houses, killing one man, and taking another prisoner.” Baltimore’s enemies had no direct proof, but they could only assume that the natives were under his authority, especially since his government maintained such close alliances with local tribes, and even employed Jesuits to work among the Indians.17

The decade after 1660 represented a period of relative calm in the colony, but by 1676 discord returned. In the wake of Bacon’s Rebellion in neighboring Virginia, opponents of the new Lord Baltimore, Charles Calvert, sent an appeal to England that expressed many of the fears that would become commonplace around the colonies in the next decade. The “Complaint from Heaven” represented Baltimore as a partner in a global Catholic design: “the platt form is, Pope Jesuit determined to over terne Engl[an]d with feyer, sword and distractions within themselves, and by the Maryland Papists, to drive us Protestants to Purgatory … with the help of French spirits from Canada.” The petition used the Catholic plot to explain recent attacks by Susquehanna Indians, as well as the unwillingness of Baltimore and Virginia governor Sir William Berkeley to meet the Indian threat. The “Huy and crye” also described a plan by Jesuits to infiltrate the colonies by sending priests in disguise. “These blake spirits disperse themselves all over the Country in America,” the writers claimed, and held secret correspondence with French Jesuits, plotting destruction for American Protestants. The petitioners used this argument to plead for an end to Baltimore’s government and, in direct contrast to those in New England, for an increase in royal authority. In order to defend against French Catholics and their Indian allies, the writers suggested that the king send “a Vice Roye or Governor Generallissimo” to preserve the colonies from external enemies.18

In 1681 these fears of Catholics and Indians combined to create a crisis that foreshadowed later troubles in New England. The problems began in the summer, when some “heathen Rogues” attacked the borders of the colony, killing several settlers on the upper reaches of the Patuxent and Potomac Rivers. These Indian attacks, probably Iroquois or Susquehanna strikes against people they believed were harboring their enemies, caused massive panic in both Maryland and Virginia, where inhabitants became “greatly dissatisfied” that their governors could not protect them from the enemy. In this climate of fear, some eventually concluded “that it is the Senaco Indians” who had committed the depredations “by the Instigacon of the Jesuits in Canada and the Procuremt of the Lord Baltemore to cut of most off the Protestants of Maryland.” This identification reflected the tendency among colonists in the Chesapeake to describe all northern Indians as “Senecas,” in reference to the westernmost nation of the Iroquois Confederacy, and constituted the most elaborate theory to date of how Baltimore, French Catholics, and Indians had banded together. The proprietor blamed “some evile ill disposed spirits” for spreading these rumors, and he pointed to two men in particular: Josias Fendall and John Coode.19

The two ringleaders of the opposition in 1681 were among the most interesting and enigmatic figures in early Maryland history. Fendall had been a governor under Cecil Calvert, but the proprietor removed him from office for his role in fomenting a previous rebellion in 1660; since that time he had stayed out of politics but remained an irritant to the proprietary interest. Coode was a younger man and a more recent arrival to the colony. An ordained Anglican minister, he served in the colony’s lower house as a representative of Calvert County, and had not yet acquired the reputation as a “perennial rebel.” While the two men’s motivations are not entirely clear, they tapped into a deep undercurrent of fear and resentment that had the potential to topple the government.20

Coode allegedly began his plotting in May 1681 at the house of Nehemiah Blackiston, when he said in the company of many people that within four months no Catholic would own “a foote of land” in the province, and that Coode could “make it high water” whenever he pleased: meaning that he had the power to cause a popular insurrection. (Coode objected to that assertion, claiming he was only “alludeing to a bowle of Punch wch they were then drinking wch he could make ebb or flow at pleasure.”) He apparently put his plan into operation in July after the murder of one Thomas Potter and some other English people near Point Lookout. When a neighbor observed that Indians killed the colonists, Coode responded that they “were not murdered by Indians, but were Murdered by Christians,” a clear implication of Catholic authorities.21

Fendall harbored the same suspicions. One of his employees reported that around the time of the murders Fendall “did severall times say that he beleived in his Conscience the Papists and Indians joined together, and that … my Lord [Baltimore] did uphold them in what they did, and he beleived my Lord and they together had a mind to destroy all the Protestants.” The rumor may have originated with Daniel Mathena, a neighbor in Charles County who had received an Indian visitor en route to deliver a packet of letters to the “Senecas” several years earlier, containing, Mathena claimed, orders from Lord Baltimore “to come and cutt off the Protestants.” His evidence was not compelling, and showed the intellectual leaps that English people made when they feared a conspiracy was afoot. The Indian visitor mentioned that he carried letters from Baltimore to the Senecas, and when Mathena’s wife asked how the Indians could read the letters, “the Indian answered that the French were hard by and that they could read them.” After the murders, this rather obtuse report of French presence in the backcountry became solid evidence of a massive popish plot.22

Fendall and Coode decided to take action. They visited Nicholas Spencer, the secretary of Virginia, notifying him “that the Papists and Indians were joined together.” Spencer, for his part, discounted the rumors and advised them to “be quiett at home,” advice that prompted Coode to swear “God Damn all the Catholick Papist Doggs” and resolve to “be revenged of them, and spend the best blood in his body.” The two men’s motivations cannot be known for certain. Fendall in particular seems to have been attempting a return to political power, and understood that the Indian troubles provided an opportunity to undermine his old rival; one man reported that Fendall “hath been soliciting the people to choose him Delegate in the Assembly and hath told them that were he Commandr of the County Troope he would Destroy all the Indians.” Additionally, witnesses implied that both men hoped to increase their property holdings by confiscating land from Catholics. At the same time, Coode’s actions remain somewhat more difficult to interpret. He already possessed both a seat in the lower house and a militia commission. While most historians have branded him a self-interested demagogue, his anti-Catholicism appears to have been heartfelt, if not always internally consistent.23

Baltimore responded to these threats by throwing Fendall and Coode in prison. Motivated by memories of Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia and the numerous insurrections his father had faced, the proprietor believed that only decisive action would demonstrate the consequences of rebellion. His approach backfired, however, because he underestimated the degree of popular support for the two men’s actions. For one thing, the lower house refused to remove Coode from its ranks or even discipline him. More ominously, a Charles County justice of the peace named George Godfrey hatched a plot to break Fendall out of prison, receiving commitments from forty men at church one Sunday. The design failed, and Godfrey joined the two other malcontents in jail. In November colonial authorities put the men on trial and convicted Fendall, who was banished from the colony, and Godfrey, whose death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. The jury acquitted Coode, leaving him free to get his revenge another day.24

The denouement of the episode represented only a partial victory for Baltimore. He remained in control of the colony, but did little to regain the trust of his people. According to authorities in Virginia, Maryland remained dangerously unstable throughout the 1680s. A letter from the end of 1681 suggested that the proprietor only retained control by “keeping forces in Armes” and imprisoning anyone who questioned his authority, leaving “the Common people in great dread and feare.” A report by Virginia governor Thomas Culpeper about the same time noted that “Maryland is now in Ferment, and not onely troubled with our disease, pouverty, but in very great danger of falling into peeces whether it be that the Old Lord Baltimores politick Maximes are not pursued and followed by the Sonne or that they will not doe in this Age.” In recognition of the precarious nature of imperial politics, Culpeper implored the Lords of Trade to take steps to stabilize Maryland, lest the disease spread to its neighbors.25

The governor’s warning proved to be prescient. While Baltimore’s political difficulties appeared to be peculiar to his own situation as a Catholic ruler in a Protestant colony, the same political language could apply throughout the English colonies. In essence, ordinary Marylanders were attempting to explain the inexplicable: why a distant, mysterious Indian nation had decided to attack them, seemingly without provocation. With reports of popish plots traveling around the English world at this time, many colonists easily molded the familiar language of antipopery to this unfamiliar situation, implicating both the French and local Catholic leaders whose loyalty seemed to be suspect. In a sense, however, Baltimore’s Catholicism was not the main issue. As future events would show, the same tactics could be used against Protestants as well.

• • •

If rumors of a Catholic-Indian conspiracy proved particularly potent in Maryland, by the 1670s they had begun to appear all over the colonies. The ubiquity of these fears came out clearly in the travel journal of two members of an obscure Dutch Calvinist sect, the Labadists, who ranged from Maryland to Boston in 1679 and 1680 looking for land for their communitarian settlement. The two men, Jasper Danckaerts and Peter Sluyter, heard talk of popish plots almost everywhere they went. In Maryland they learned that Jesuit priests “hold correspondence” with all the Indians between the English and French colonies, and related that “some people in Virginia and Maryland as well as in New Netherland, have been apprehensive lest there might be an outbreak, hearing what has happened in Europe, as well as among their neighbors at Boston.” Once they reached New England, meanwhile, popular anxiety began to have a deleterious effect on the men’s travels. As strangely dressed foreigners Danckaerts and Sluyter stood out, and many Bostoners feared they were papists in disguise. “Some declared we were French emissaries going through the land to spy it out,” Danckaerts noted, “others, that we were Jesuits travelling over the country for the same purpose; some that we were Recollets, designating the places where we had held mass and confession.” Only with some difficulty—and a lot of explanation—were the two men able to find lodging in the town.26

These fears came out of several recent incidents. The most distant was in 1673, when a similar European stranger appeared in Boston during a more innocent time. The man proved to be an astute scholar, and he charmed New England’s clerical elite with his wit and learning. In time he began to raise suspicions, however, because “although he was disguised,” New Englanders believed the man might be a Jesuit. In fact, he was a priest named Jean Pierron, a member of the Society of Jesus stationed in Acadia who had spent the winter exploring the English colonies. In particular, he had sought to create ties between French and Maryland Jesuits, perhaps inspiring the fears of coordination expressed by Marylanders in the 1676 “hue and crye.” Only after his departure from Boston did the townspeople realize that an inveterate enemy had been among them; Pierron boasted on his return he had converted several “heretics” to the Catholic faith.27

Several years after this unwelcome visit a major Indian war convulsed the region. The paramount Wampanoag sachem in the region, known to the English as King Philip, led a coalition of Algonquians who threatened the colony’s very existence in 1675 and 1676. The region’s leaders agonized over the causes of the war, and most came to blame sin and backsliding. God was angry, the ministers said, and they demanded a return to the zealousness of the colony’s founding years. For some people, however, there was another explanation: it was priests like Pierron who inspired the bloodshed. Just after his arrival in Boston the royal agent Edward Randolph heard that “vagrant and Jesuitical priests” had worked for years “to exasperate the Indians against the English, and to bring them into a confederacy, and that they were promised supplies from France, and other parts, to extirpate the English Nation out of the Continent of America.” This alternate explanation for the war seemed more persuasive after the General Court voiced its suspicions that the French had supplied arms to the enemy, several of whom had taken refuge in New France. Indeed, charges of French collusion became common both during and after the war, in spite of the lack of any real evidence.28

The next evidence of a plot against America came in 1679, when a fire raged through Boston, destroying much of the town’s North End. Such conflagrations were not uncommon in early modern towns and cities, but New Englanders naturally suspected that papists had a hand in the disaster, since they were known to favor such tactics: many people continued to believe that the London fire of 1666 was a Catholic affair. Suspicion came to rest on a Frenchman named Peter Lorphelin, and though investigators could find no sufficient evidence to tie him to the crime, word of the fire traveled through Protestant networks as far as Ireland and the Netherlands. It appeared to many that the papists were beginning to pay attention to America, and some people at least were inclined to think of Indians as partners in the design.29

In 1680, nonetheless, most American colonists continued to view Catholics and Indians as two distinct threats. When Indians captured a young New Englander named Quentin Stockwell in 1677 and carried him to Canada, for instance, he never made any connection between the two groups, and praised the French for providing food and care for him during a sickness. He even related an argument between the French and Indians regarding his treatment, after which the natives charged that the French “loved the English better than the Indians.” For Stockwell, the civility and Christianity of the French was enough to place them above the Indians, whom he perceived as cruel pagans. But if he could separate the two groups in 1677, other New Englanders began to view them as partners in the same cause. Two broad changes began to occur: first, the English saw Indians as turning French, especially in their increasing adherence to the Catholic faith; and second, the French began to look more like Indians, due to their tolerance for miscegenation and ability to adapt to backcountry life.30

During the 1680s periodic violence continued to plague the New England frontier. But more damaging than actual attacks were the rumors, usually bringing reports of a new Indian conspiracy. In 1682 at the Cape Porpoise River Falls Mill in Maine, for instance, reports circulated that nearby Abenaki Indians “doe Intend to Rise again this Summer,” gathering at the head of the Merrimack River “so to destroy so far as thay Can.” Around the same time New Hampshire’s Governor Edward Cranfield claimed that the “Indiens … are well Armed by the French which makes them verry Insolent.” Two years later an Indian boasted to an Englishman in Pemaquid “that he would Burne the English houses and make the English Slaves to them as they ware Before,” and others added “that they would go to Canada and fetch some strength to fall on the English and some of the Chefe of them is gon to Canada all Ready to fetch guns and amanition and they said they would make the greatest armie that ever was yet among them.”31