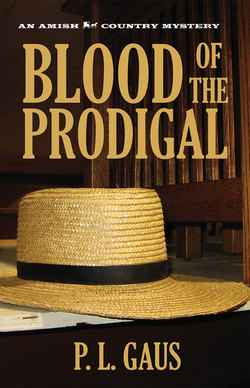

Читать книгу Blood of the Prodigal - P. L. Gaus - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

Thursday, June 18

4:30 P.M.

“I TOLD Cal you’d take the case, Michael,” Caroline said as she gathered up the scattered pages of her manuscript, smiling outwardly at her husband and inwardly at her gentle mischief.

Branden carried two more mugs onto the spacious back porch and poured coffee for himself and Cal. “It’s wiser to be a historian than a prophet, Caroline,” he scolded.

Caroline turned to Cal, taunting. “The Professor doesn’t like to be thought so predictable.”

Cal held out his palms in mock surrender, laughed, and sidestepped the jab by pointing to Caroline’s loose stack of papers. “Another book?”

“It’s a revision of a collection of children’s stories I edited a few years ago,” Caroline said. She stacked the pages on edge, laid the manuscript on the glass-topped patio table where she had been working, and joined them in white wicker chairs by the porch windows. The day had begun brightly, but now a front was coming in from the north. A cool afternoon breeze blew through the tall screens of the porch.

The porch was more than spacious, running the entire length of the two-story brick colonial, extravagantly wide and screened on three sides, with windows stretching from floor to ceiling. Because of a gentle slope to the Brandens’ long back yard, the porch seemed to hover over the lawn, so that the Brandens and their guests enjoyed a spectacular view of the eastern hills and Amish valleys. In summers, the porch had come to be Caroline’s favorite place to work, and often, Branden would find her standing there, watching the hawks ride thermals, or gazing at the patchwork of Amish farms and fields in the distance.

Caroline sat in an old-fashioned, low and wide wicker chair, her legs crossed casually. She peered at Branden and Troyer over a fresh mug of coffee. “You did take the case,” she said.

“Wasn’t up to me,” Branden said. “The bishop made the decision. I just showed up for the interview.”

“How’d that go?” Cal asked.

“Slowly, as you predicted,” Branden said. “We toured Holmes County for over an hour before he asked anything about me.”

“Typical,” Cal said.

“Mostly we talked about the people and the farms we passed. In remote regions of the Doughty Valley. He showed me each of the family farms under his leadership. Named all of the children, parents, grandparents, land holdings, livestock, relatives, and relationships. Even courtships. Essentially, he introduced himself to me by detailing all of the district over which he serves as bishop. Eventually, he wanted to know about me. And Caroline. And whether we had any children.”

Cal glanced at Caroline and saw the memory of her losses pass heavily across her eyes. Troyer and Branden exchanged glances, wondering how she would handle a case involving a child.

Eventually Caroline asked, “Does he have a lot of children?”

“Fourteen. Thirteen living,” Branden answered gently, grateful to see her strength. He wondered again, briefly, how he’d mention the Federal Express envelope to her. Wondered how she would handle the prospect of moving to the new university professorship he had been offered.

He took a moment, turning his coffee mug in his fingers, sipping from it thoughtfully, and then said, “Actually that’s the whole point of this case. His children, that is. One of his sons, Jonah Miller, is dead to them, but still alive.”

He glanced from Cal to Caroline, giving them a chance to think it through.

“He left home?” Cal asked.

“Shunned,” Branden answered, pointedly.

“His own son?” Caroline said. “That’s hard to believe.”

“He’s the bishop,” Branden answered. “If anyone in that district were to have been mited, the bishop would have done it himself.”

“I would have hoped the mite was a thing of the past,” Caroline said.

“He wouldn’t have had any choice,” Branden said. “He’s the bishop.”

“Many of them would not so much as have spoken his name,” Cal added.

“Then there’s more to this case than the custody of a boy,” Branden said. Cal and Caroline waited for an explanation. “Bishop Miller did actually speak his son’s name, once. At the end of our interview, Cal. He said something like, ‘It’s my son, Professor, who has the boy. Jonah E. Miller. He’s been lost to us for nearly ten years.’ Then he handed me this note.”

Branden gave the note first to Cal. When Cal had read it, he passed it, disquieted, to Caroline. She read it out loud.

Dear Father.

I want my boy to see some of the world.

You’ll have him back in time for harvest.

Do not try to find us.

Jonah.

“Extraordinary,” Cal said after a pause. He ran the fingers of both hands back through his long white hair.

“Because of the note?” Caroline asked.

“Yes, but more,” Cal said. He slouched in his white wicker chair, his stocky legs out straight and crossed at the ankles, coffee mug balanced on his belly, eventually saying only, “There must be more.”

“Agreed,” Branden said. “Let’s think it through.” He leaned forward, rested his elbows on his knees, and counted out each assertion on the fingers of his left hand. “First, the bishop put the ban on his own son, ten years ago.” The first finger went up.

“Must have been good cause,” Cal said.

“Indeed,” Branden said, and another finger went up. “Also, the bishop evidently thinks there’s good cause, now, to involve outsiders in this case.” A third finger popped up.

Cal stood up, walked over to the large windows of the screened porch, ran his eyes out toward the far hills in the east, and said, “He’d not have mentioned his son, or have involved us in this case, if it were simply a matter of a father taking his boy for the summer.”

“Precisely,” Branden said, and held up a fourth finger.

“Whatever the reason, his Dieners would have concurred,” Cal said.

“Right again,” Branden said, and lifted his thumb.

“You’d think that if the bishop were really worried about his grandson, he would have gone to the police,” Caroline said.

“They don’t trust them,” Branden said.

“Partly,” Cal said. “More likely, they think it’s not yet necessary. They simply haven’t gotten to the point where they think that the police need to be involved.”

“So,” Caroline said, “you’ve been asked to help the Old Order Amish find Bishop Miller’s grandson, who has evidently been taken for the summer by his father. The father was earlier shunned by his people. The note says that the boy will be returned at the end of the summer.”

“By harvest,” Cal interjected.

“Where’s the boy’s mother?” Caroline asked.

“Dead, according to the bishop.”

“Do we know who she was?” Caroline asked.

“No,” Branden said. “The bishop wouldn’t speak of her at all. Just that Jonah met her in a bar and left town before the child was born. The bishop and his wife took in the boy as an infant and have raised him since then. That’s all he would say.”

“Should be easy enough to find out who she was,” Caroline volunteered. “Doesn’t sound likely she was Amish.”

“No, and that could mean her folks would be more willing to talk about Jonah,” Cal observed.

After a moment in thought, Branden said, “It’s unusual for the bishop to have approached Englishers for help. And I agree with Caroline. Why come to us instead of the police?”

“That’s not out of line at all. They’d be unlikely, whatever the circumstances, to involve the police,” Cal said, and eased himself back down into one of the white wicker loungers.

“If you push this concept through to its logical extreme, this is a kidnapping case,” Caroline said. “It’s not just a ‘grand summer away with father.’”

“Their distrust of secular authority runs deep,” Cal said. “It’s part of their suspicion of outsiders. And governmental authorities are the most suspect of them all.”

Branden stood, paced to the far end of the porch, stuffed his hands into his pockets, and said, “I still don’t see a compelling reason for them to have come to us.”

“Perhaps one summer out in the world is more than they think the boy can handle,” Caroline offered.

“Yes, but there’s got to be more to this case than Miller’s let on,” Branden said.

“We’ll get little more out of him at this point,” Cal said. “We’ve already been told more than I would have expected.”

Branden said, “Then we’ll have to find out more from other sources, obviously.”

“That’ll take some time,” Cal said.

“There really isn’t much time left at all, when you consider what a cold start we’ll have finding Jonah,” Branden said. “The bishop gave it a month. Said something like ‘a month from now and it won’t matter anymore.’”

“He said the same thing to me,” Cal told Caroline.

“Before what?” Caroline asked. “If you believe the note, at the very worst, the boy’ll be gone for the summer and then brought home for harvest.”

They each fell silent and thought, Cal and Caroline seated, Branden pacing in front of the windows. Dense, billowing clouds had gathered over the valley. The afternoon breeze had grown chill.

Eventually, Branden said, “I keep coming back to the fact that the Amish, who insist on independence and self-reliance, have engaged the assistance of outsiders to solve what is essentially a family dispute over a boy.”

After a few quiet moments, Cal said, “We need to know more about the boy’s father, Jonah Miller.”

“How?” Branden said. “No one will talk to us about him.”

“No Amish will,” Caroline said. “But how about the authorities? Police, social services, schools, neighbors who are not Amish. Anywhere someone might have known Jonah E. Miller.”

“Or those who know Eli Miller,” Cal said.

“Good point,” Branden said. “Also the preachers and deacons in neighboring districts.”

“How about relatives of the boy’s mother?” Cal said.

“Maybe her folks have been in touch with Jonah,” Branden said.

“Good luck,” Cal said with obvious pessimism.

Branden stood at the windows for a while longer with his gaze focused on the distant hills, pale green under cover of gathering clouds.

Caroline asked, “Didn’t his teachers ask about Jeremiah?”

“The bishop told them he was needed on the farm,” Branden said.

Cal scoffed and then said, “I’ve got a few days yet. Maybe I can work on Amish folk who know the bishop. I might find one who’s willing to talk.”

“A few days before what, Cal?” Caroline asked, concern evident in her tone.

“Sorry, Caroline. Next week’s when I leave for the missions conference.”

“How long will you be gone?” Branden asked.

“A week. Too long for me to be of much help to the bishop. I’m hoping you’ll have it wrapped up before I’m back.”

“We’ll need your help, Cal,” Branden said. “Especially for talking with Miller’s neighbors.”

Troyer shrugged apologetically and said, “I’ve got half a week before I leave. I’ll get you started, Mike, but mostly you’re going to have to work this one yourself.”

“Then I’ll help,” Caroline said. “Teachers, newspapers, neighbors, that sort of thing.”

“Don’t you have a deadline on your book?” Branden asked.

Caroline shrugged and said, “I’ll do what I can, Michael.”

As they cleared the dishes, Branden added, “Just one more thing. I don’t know why, but the bishop has insisted on special conditions. He’s accepted our help only because he trusts that we’ll abide by those restrictions.”

He paused to let his words have effect and then said, “We can’t let on to anyone that the boy is being held against his will. Or that he might be harmed. We are especially not to tell the law that Jonah has Jeremiah. He only wants us to investigate whether or not the boy and his father can be found. If they can be found, we are supposed to decide, without approaching the father, whether or not we think the boy can be returned to the family. I have also given the bishop my word that we will not attempt to take the boy from his father. We’re simply to locate the two of them, find out the boy’s condition, and advise the bishop. Nothing more.”

Caroline and Cal glanced curiously at each other and then at Branden, waiting for an explanation.

“For some reason,” Branden said, “the bishop is afraid to force the return of his grandson. If we can’t turn something up in the next few weeks, he’ll wait out the summer until harvest, rather than cause a ruckus now.”

“I don’t get it,” Caroline said. “Does he want the boy back or not?”

“His restrictions, for now, are quite specific,” Branden said. “We can look for the boy diligently, but we are not to make it appear that Miller is seeking to force the return of his grandson. He was very clear on this. Said something like, ‘For now, Professor, we must be very cautious. Just see if you can find him, and then let me know.’”

“To what end?” Caroline asked.

“I don’t know, exactly,” Branden said. “Maybe he just wants to make sure that the boy will be safe until harvest. And that’s all we can do. Maybe once he knows where the boy is, he’ll bring him home, himself. Keep it in the family. You know how clannish they can be. Secretive, even. That’s why I promised to abide by his restrictions. They’ll not accept our help on any other terms, and they’ll certainly never go to the police with the matter. So finding the boy is something we’ll have to do on our own, and even that, as little as it is, is an amazing and unusual thing for a bishop to have asked an Englisher to do.”

“Working through the sheriff’s office would be the best way to find them quickly,” Caroline said.

“We can’t tell the law, any law, about Jeremiah’s being gone.”

Cal said, “You’d expect that sort of resistance from Old Order Amish.”

“I think the bishop is being a little foolish,” Caroline said.

Branden reiterated, “They won’t take our help unless it’s on their terms, Caroline.”

Cal said, “But Caroline’s right, of course. The sheriff could do this faster.”

“Believe me, I agree,” Branden said. “That’s not the issue. It’s the bishop. He’s setting the rules, and I promised I’d do things his way, so that’s the way it has to be. He was very specific about that. Said that if the law got tangled up in the matter, he’d deny ever having a problem in the first place.”