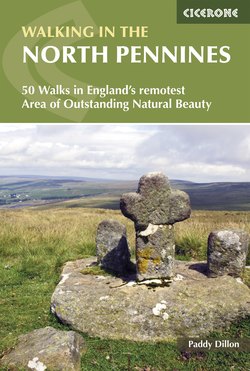

Читать книгу Walking in the North Pennines - Paddy Dillon - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The North Pennines has been called ‘England’s last wilderness’, and there is nowhere else in the country where the land is so consistently high, wild, bleak and remote. In fact, this is a region of superlatives – once the world’s greatest producer of lead, location of England’s most powerful waterfalls, holding several records for extreme weather conditions, home to an assortment of wild flowers, and refuge for most of England’s black grouse population. The region is protected as an ‘area of outstanding natural beauty’, and renowned for its wild and wide-open spaces.

There is plenty of room for everyone to enjoy exploring the North Pennines, with walking routes to suit all abilities, from old, level railway trackbeds to extensive, pathless, tussocky moorland. For many years the region was relatively unknown, being surrounded on all sides by more popular national parks. Since 1965, the Pennine Way has introduced more and more walkers to the region, many of them being surprised at how wild this part of the Pennines is, especially when compared to the gentler, greener Yorkshire Dales.

When national parks were being established in England and Wales, the North Pennines was overlooked. John Dower described a national park as ‘an extensive area of beautiful and relatively wild country’. The North Pennines features an extensive area of supremely wild country that isn’t matched on the same scale in any of the national parks. The Hobhouse Committee recommended that 12 national parks should be created, and also identified other areas with great landscape value, many of which were subsequently designated as ‘areas of outstanding natural beauty’, or AONBs. The North Pennines was notably absent from all these listings.

When a document recommending AONB status for the North Pennines was presented to the Secretary of State for the Environment, it was promptly filed and forgotten. A concerted lobby brought it back to the fore and a public enquiry was launched. The North Pennines became a minor battleground, with ‘No to AONB’ signs appearing in some places, while some landowners declared that their property had no beauty. In June of 1988 the North Pennines was at last declared an area of outstanding natural beauty, becoming the 38th such designation and, at 2000km2 (772 square miles), also the largest at that time. This was almost immediately followed by a renewed call for national park status to be granted.

The AONB boundary is roughly enclosed, in a clockwise direction, by Hexham, Consett, Barnard Castle, Kirkby Stephen, Appleby and Brampton. While all those places lie outside the boundary, each could be considered a ‘gateway’ to the North Pennines. The largest town inside the AONB is Alston, but Stanhope and Middleton-in-Teesdale are only just outside the boundary.

The AONB includes all the high ground and most of the dales, though half of Teesdale and Weardale are excluded, along with the large forests at Hamsterley and Slaley. Some land south of the busy A66, which was never claimed by the Yorkshire Dales National Park, has been included in the North Pennines. The counties of Cumbria, Durham and Northumberland each claim a third share of the North Pennines, and an office administering the AONB has been established at Stanhope.

The North Pennines was once the world’s greatest producer of lead, providing everything from roofing material for churches to lead shot for warfare. A considerable quantity of silver was also mined. The broad, bleak and boggy heather moorlands have long been managed for the sport of grouse shooting, and are best seen when flushed purple in high summer. For many years, walkers wanting to reach the most remote and untrodden parts of the North Pennines might have been put off because of the lack of rights of way, but the recent Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 has resulted in vast areas being designated ‘access land’.

There has probably never been a better time to explore the North Pennines and this guidebook contains detailed descriptions of 50 one-day walks. These cover nearly 800km (500 miles) of rich and varied terrain, serving to illustrate the region’s history, heritage, countryside and natural wonders. This terrain ranges from field paths and old railway tracks to open moorlands on the high Pennines. You will be able to discover the region’s geology, natural history and heritage by following informative trails, or taking in specific sites of interest along the way. A network of tourist information centres can help you discover the best places to stay, how to get around and what to see.

Geology

The geology of the North Pennines can be presented in a fairly simple manner, but can also become extremely complex in some areas. The North Pennines was designated the first ‘Geopark’ in Britain in 2003, in recognition of how its geology and mineral wealth have shaped the region. The oldest known bedrock is seldom seen at the surface, but is notable along the East Fellside. Ancient Ordovician rock, comprising mudstones and volcanics, features on most of the little hills between the Vale of Eden and the high Pennines, but being heavily faulted, tilted and contorted, is very difficult to understand, even for students of geology. Ordovician rock is about 450 million years old and lies beneath the whole of the North Pennines. There is also a significant granite mass, known as the Weardale Granite, which outcrops nowhere, but was ‘proved’ at a borehole drilled at Rookhope.

Late-flowering hayfields can be enjoyed in Upper Teesdale and Upper Weardale (Walk 28)

Looking back to the Carboniferous period, 350 million years ago, the whole area was covered by a warm, shallow tropical sea. Countless billions of shelled, soft-bodied creatures lived and died in this sea. Coral reefs grew, and even microscopic organisms sometimes had a type of hard external or internal structure. Over the aeons, these creatures left their hard shells in heaps on the seabed, and these deposits became the massive grey limestone seen on the fellsides and flanks of the dales today. A dark, durable, fossiliferous limestone outcropping in Weardale is known as Frosterley Marble. Even though it is not a true marble, it polishes well and exhibits remarkable cross sections of fossils.

Even while thick beds of limestone were being laid down, distant mountain ranges, being worn away by storms and vast rivers, brought mud, sand and gravel down into the sea. These murky deposits cut down the light in the water and caused delicate coral reefs and other creatures to die. As more mud and sand were washed into the sea, a vast delta system spread across the region.

Frosterley Marble

At times, shoals of sand and gravel stood above the waterline, and these became colonised by strange, fern-like trees. The level of water in the rivers and sea was in a state of fluctuation, and sometimes the forested delta would be completely flooded, so that plants would be buried under more sand and gravel. The compressed plant material within the beds of sand and mud became thin bands of coal, known as the Coal Measures. This alternating series of sandstones and mudstones, with occasional seams of coal, can be seen all the way across the region. The various hard and soft layers can often be detected where the hill slopes have a vaguely stepped appearance today.

Other geological processes were more violent, resulting in the fracturing and tilting of these ordered sedimentary deposits. The whole series is tilted so that the highest parts of the Pennines are to the west, diminishing in height as they extend east. Far away from the North Pennines, there were violent volcanic episodes, and at one stage a sheet of molten rock was squeezed between existing layers of rock, solidifying as the ‘Whin Sill’. Deep-seated heat and pressure brought streams of super-heated, mineral-rich liquids and vapours into cracks and joints in the rocks. These condensed to form veins of mixed minerals, which included lead, silver and copper. Associated minerals are barytes, quartz, fluorspar, calcite, and a host of other compounds. Coal mines and stone quarries are found throughout the North Pennines, and the region was once the world’s greatest producer of lead.

Most of the rock seen by visitors around the North Pennines is Carboniferous. Younger rocks are found outside the region, such as the New Red Sandstone in the Vale of Eden, formed in desert conditions, and the soft Magnesian Limestone in the lower parts of County Durham, formed in a rapidly shrinking sea beside the desert. Apart from being lifted to great heights, the only other notable geological occurrence in the North Pennines was during the last ice age, when the whole region was buried beneath a thick ice sheet for about two million years, completely freeing itself from such conditions only 10,000 years ago.

Walkers who wish to delve more deeply into the geology of the North Pennines could equip themselves with specialised geological maps and textbooks, or explore the region in the company of knowledgeable experts. The North Pennines was designated as a UNESCO Global Geopark in 2015. Look out for ‘Geopark’ leaflets describing geological trails and curiosities. From time to time, guided walks are offered that feature geology, as well as visits to mines.

THE WHIN SILL

Many dramatic landforms around the North Pennines and beyond owe their existence to the Whin Sill. This enormous sheet of dolerite was forced into the limestone bedrock under immense pressure in a molten state around 295 million years ago. As the heat dissipated, the limestone in contact with the dolerite baked until its structure altered, forming the peculiar crystalline ‘sugar limestone’ which breaks down into a soil preferred by many of Teesdale’s wild flowers.

While weathering, the Whin Sill proves more resistant than the limestone, forming dramatic cliffs such as Holwick Scars, Cronkley Scar and Falcon Clints. Where the Whin Sill occurs in the bed of the Tees, its abrupt step creates splendid waterfalls such as Low Force, High Force, Bleabeck Force and Cauldron Snout.

The rock has been quarried throughout this part of Teesdale, generally being crushed and used as durable roadstone. It outcrops from time to time along the East Fellside, most notably at High Cup, where it forms impressive cliffs. Outside the North Pennines, the Whin Sill is prominent as a rugged ridge carrying the highest stretches of Hadrian’s Wall, and it features regularly as low cliffs along the Northumberland coast, including the Farne Islands.

The River Tees displays some of the finest and most powerful waterfalls in England (Walk 25)

Landscape

Many visitors are drawn to the North Pennines to enjoy its extensive and apparently endless moorlands, while others are content to explore the gentler green dales. The scenery is remarkably varied, but the sheer scale of the open moorlands is amazing. Almost 30 per cent of England’s blanket bog is in the North Pennines. It is worth bearing in mind that the moors are entirely man-managed, grazed by sheep in grassy areas and burnt on a rotation basis to favour the growth of heather as food and shelter for red grouse. Left to nature, without sheep grazing and interference by man, most of the moorlands would revert to scrub woodland, with dense forests filling the dales. Open moorlands are splendid places to walk, with due care and attention – more cautious walkers may prefer to stay closer to the dales, within reach of habitation.

The dales of the North Pennines are each quite different in character. Teesdale is famous for its powerful waterfalls, while Weardale offers more to those in search of industrial archaeology. Both dales are lush and green, grazed by sheep, with small woodlands and hedgerows providing varied habitats for wildlife. Forty per cent of England’s upland hay meadows are located in the upper dales. The northern dales are charming, but sparsely settled, except for South Tynedale, which is dominated by the remarkable little town of Alston, clinging to a steep slope.

The East Fellside flank of the North Pennines is awe-inspiring, where the Vale of Eden gives way to a striking line of conical foothills, while the Pennine massif rises steep and unbroken beyond, maybe with its highest parts lost in the clouds.

There are few forested areas in the North Pennines. Apart from the forests at Hamsterley and Slaley, which actually lie outside the AONB boundary, only small blocks of coniferous forest are found. The last remaining ‘wildwoods’ are around Allen Banks and Staward Gorge in the north, though there are many pleasant woodlands tucked away in all the dales.

There are no large lakes in the North Pennines, but there are several big reservoirs, constructed to slake the thirst of distant towns, cities and industries. Apart from Cow Green Reservoir in the heart of the North Pennines, there is a reservoir at the head of Weardale, several around Lunedale and Baldersdale in the south, and the Derwent Reservoir and a couple of smaller reservoirs in the east.

It is quite possible to choose routes in the North Pennines that stay exclusively on high moorlands without a break, day after day, but most of the routes in this guide include more variety. The long-distance Pennine Way passes through some of the highest and wildest parts of the region, but also includes visits to villages and has long stretches that stay low down in the dales.

Mining

There are no longer any working mines in the North Pennines, but some of the old lead-mining sites have been preserved. The remains of former industry are best explored around the dale-heads at Killhope, Allenheads and Nenthead, but there are literally dozens of other interesting sites that are encountered throughout the region. The general rule, when faced with an opening to an old mine, is to keep out. These holes, and the buildings associated with them, are often in a poor state of repair and prone to collapse when disturbed. Only explore in the company of an expert.

Some old mining sites have been transformed into heritage features, such as the Nenthead Mines (Walk 50)

Coal mining developed through the centuries in these hills, with bell pits such as those observed near Tan Hill giving way to deeper shafts and levels. Mines in the North Pennines were small compared to the ‘super pits’ that were later opened to the east in County Durham. Some of the coal had to be used to service the steam engines, including locomotives and static winding engines, working the railways that served some of the larger mining sites.

Weather

Some years ago, the North Pennines briefly featured a holiday experience with a difference, called ‘Blustery Breaks’. The idea was not to moan about the weather, but to capitalise on it, offering visitors a chance to understand why the North Pennines is associated with extreme weather conditions. It all comes down to the fact that the region is consistently high, with very few breaks that moving air masses can exploit. Put simply, all the wind and weather has to go ‘over the top’, which results in rapid cooling, leading to condensation, cloud cover, rainfall, and in the winter months, bitter cold and snowfall. There is a weather station on top of Great Dun Fell, the highest of its type in England, and naturally this has logged record-breaking conditions.

The North Pennines are broad, bleak, remote and at times subject to wet and windy weather (Walk 8)

The broad, bleak moorlands of the North Pennines offer little shelter from extreme weather, so anyone walking in the rain is going to get wet. Anyone walking in mist will find it featureless. Anyone walking in deep snow will find it truly debilitating. It’s important to check the weather forecast then dress accordingly. The extensive moorlands are mostly covered in thick blanket bog, great depths of peat that absorb and hold prodigious quantities of water. Sometimes, these stay sodden even during a heatwave. The best time to walk easily across wet blanket bogs is during a hard frost when they are frozen solid!

The Helm Wind

Most visitors to the North Pennines hear about the Helm Wind, but few really understand what it is. The Helm Wind is the only wind in Britain with a name. It only blows from one direction, and gives rise to a peculiar set of conditions. Other winds may blow from all points of the compass, from gentle zephyrs to screaming gales, but the Helm Wind is very strictly defined and cannot be confused with any other. (The last time the author explained how the Helm Wind operated, a film producer from Australia beat a path to his door to make a documentary about it!)

To start with, there needs to be a northeasterly wind blowing, with a minimum speed of 25kph (15mph), which the Beaufort Scale describes as a ‘moderate breeze’. This isn’t the prevailing wind direction and it tends to occur in the winter and spring. Now, track the air mass as it moves off the North Sea, across low-lying country, as far as the Tyne Gap around Corbridge. The air gets pushed over Hexhamshire Common, crossing moorlands around 300m (1000ft). Next, it crosses the moors above Nenthead, around 600m (2000ft). Later, Cross Fell and its lofty neighbours are reached, almost at a level of 900m (3000ft). There are no low-lying gaps across the North Pennines, so there is nowhere for the air mass to go but over the top.

As the air has been pushed ever-upwards from sea level, it will have cooled considerably. Any moisture it picked up from the sea will condense to form clouds, and these will be most noticeable as they build up above the East Fellside. This feature is known as the Helm Cap, and if there is little moisture present, it will be white, while a greater moisture content will make it seem much darker, resulting in rainfall. Bear in mind at this point that the air mass is not only cooler than, but also denser than, the air mass sitting in the Vale of Eden.

After crossing the highest parts of the North Pennines, the northeasterly wind is cold, dense, and literally runs out of high ground in an instant. The air literally ‘falls’ down the East Fellside slope, and if it could be seen, it would probably look like a tidal wave. This, and only this, is the Helm Wind. The greater the northeasterly wind speed, the greater the force with which it plummets down the East Fellside, and if it is particularly strong, wet and cold, it is capable of great damage. Very few habitations have ever been built on this slope, and the villages below were generally constructed with their backs to the East Fellside, rarely with doors and windows in them until the advent of modern draught-proofing.

The air mass now does some peculiar things, having dropped, cold and dense, to hit a relatively warm air mass sitting in the Vale of Eden. A ‘wave’ of air literally rises up and curls back on itself. As warm and cold air mix, there is another phase of condensation inside an aerial vortex, resulting in the formation of a thin, twisting band of cloud that seems to hover mid-air, no matter how hard the wind is blowing at ground level. This peculiar cloud is known as the Helm Bar, and is taken as conclusive proof that the Helm Wind is ‘on’, as the locals say.

Local people always say that no matter how hard the Helm Wind blows, it can never cross the Eden. All the wind’s energy is expended in aerial acrobatics on the East Fellside, where it can roar and rumble for several days, while the Vale of Eden experiences only gentle surface winds. Northeasterly winds are uncommon and short-lived, so after only a few days the system begins to break down and the usual blustery southwesterly winds are restored. In the meantime, don’t refer to any old wind as the ‘Helm Wind’ until all its characteristics have been noted, including the northeast wind, the Helm Cap and the Helm Bar.

Plants and wildlife

Although the North Pennines today features extensive moorlands, this was not always the case. From time to time, eroded peat hags reveal the roots of ancient trees – the remnants of the wildwood that once covered all but the most exposed summits. Only hardy species such as juniper or dwarf willow can survive in exposed upland areas, though some of the dales feature mature woodlands, and some marginal areas have been planted with commercial conifers. It may seem strange, but woodland plants can thrive in areas far removed from woodlands, simply by adapting to the shade provided by boulders or other taller plants. One of the best remnants of the original wildwood can be seen around Allen Banks and Staward Gorge, along with the juniper thickets of Upper Teesdale.

Many visitors are delighted to visit Upper Teesdale in spring and early summer, where the peculiar Teesdale Assemblage of plant communities is seen to best effect. Remnant arctic/alpine plants thrive on bleak moorlands – such as cloudberries on the boggiest parts. Drier areas, particularly where the soil is generated by the crumbly ‘sugar limestone’ on Cronkley Fell and Widdybank Fell, feature an abundance of artic/alpines, including the delightful spring gentian and mountain pansy. Other plants thrive in hay meadows, because haymaking traditionally starts late at Upper Teesdale and Weardale, allowing seeds to mature and drop before mowing. A trip to the Bowlees visitor centre is a fine way to get to grips with the nature and floral tributes of the region before setting off walking and exploring.

Extensive heather moorlands in the North Pennines are essentially man-managed

Cloudberries are arctic/alpine remnant plants that thrive on the boggy slopes of Mickle Fell (Walk 13)

Upper Teesdale boasts a fascinating assemblage of wild plants, including the mountain pansy (Walk 27)

Bear in mind that the extensive grass and heather moors of the North Pennines exist only because of human interference. Grassy moorland was developed as rough pasture for sheep grazing, while heather moorland was developed to provide food and shelter for grouse, to maintain a grouse-shooting industry. There should be a greater range of species on the moors, including trees and scrub woodland, but these are suppressed by grazing and rotational burning. Vegetation cover can change markedly when underlying sandstone gives way to limestone.

Most of the animal life you will see around the North Pennines is farm stock, although deer are present in some wooded areas, where they might be observed grazing along the margins of woods and forests at dawn and dusk. Britain’s most northerly colony of dormice is found at Allen Banks, and the elusive otter can be spotted, with patience, beside rivers and ponds. Reptiles are seldom seen, but adders, grass snakes and common lizards are present. Amphibians such as frogs are more likely to be seen, while toads and newts are much less common.

Birdlife can be rich and varied, but the North Pennines is notable primarily for their population of red grouse. Rare black grouse can occasionally be spotted, especially during the mating season, when they perform elaborate displays on particular parts of the moors. The placename ‘Cocklake’ is derived from ‘cock lek’, and refers to the mating displays of black grouse. For details see www.blackgrouse.info.

Late spring and early summer are important times for breeding birds. Cuckoos will be heard as they advance northwards, while skylark, lapwing, snipe and curlew are often seen on broad moorlands. Watch out for buzzards, merlins and kestrels in open areas, and red kites around Geltsdale in particular. Herons fish in watercourses, while dippers and grey wagtails will completely submerge themselves in rivers. Some gulls and waders travel from the coast to the Pennines, and it is not unusual to find raucous colonies of gulls around shallow pools high on the moors.

The enormous Upper Teesdale and Moor House national nature reserves often feature guided walks with wildlife experts. Look out for their annual events guide, which runs from March to October, with a special emphasis on the spring and summer. These reserves claim to be the most scientifically studied upland regions in the world! For details, tel 01833 622374 or go to www.naturalengland.org.uk.

Grouse shooting

Red grouse are hardy, non-migrating birds that thrive on heather moorland. They are deemed to be unique to Britain but may be related to willow grouse across Scandinavia and Russia. These plump birds spend most of their time among the heather, where they are perfectly camouflaged, and many walkers have almost stepped on them before they break noisily from cover, calling ‘go-back, go-back, go-back’. They fly close to the ground, with rapid wing-beats, seldom covering any great distance before landing. While young chicks will eat insects, adult birds chew on young heather shoots and various berries.

With so much of the high moorlands used for grouse shooting, it makes sense to be aware of this activity, and to be aware of how the moorlands are managed. The first thing to bear in mind is that extensive heather moorlands are not natural, but have to be created. Heather needs plenty of light and cannot compete with tall vegetation. It can tolerate wet ground, but cannot grow in waterlogged bogs. Moorlands may have drainage ditches cut across them to remove excess water, and they may be burnt on a rotation basis, between 1 October and 15 April. When moorland is burnt, heather seeds survive better than other species, and so the plant is quick to recover. However, even the heather itself needs to be burnt, since tall heather has limited food value to grouse, which prefer young heather shoots. Walkers, therefore, will find awkward drainage ditches, deep heather, short heather and scorched terrain. A project called Peatscapes aims to restore some areas of moorland to a natural state, including blocking drains and encouraging species diversification.

Large populations of red grouse will naturally attract predators, including foxes, various rodents and birds of prey, and grouse can also suffer from a debilitating internal parasitic worm. While some predator species are protected, particularly birds of prey, others are not, and are liable to be trapped in an effort to ‘control’ them. Sometimes, over-zealous gamekeepers have been suspected of killing birds of prey. A particularly sensitive time is spring and early summer, when grouse lay their eggs and raise their chicks, and are vulnerable to attack by predators. Nor do the eggs and chicks fare well if they are constantly disturbed. Dogs should be kept on a leash at this time, and may be banned from some areas of access land.

Once the grouse are thriving in the height of summer, and the heather moorlands turn purple, the grouse-shooting season starts on 12 August. The ‘glorious twelfth’ sees a lot of activity on the moorlands, with gamekeepers leading shooters (or ‘guns’) from around the world to specially constructed butts, while beaters are employed to drive the grouse towards their doom. Some estates charge a fortune for a day’s shoot, and there is still a tradition of getting fresh grouse to the best London restaurants for immediate consumption. When the shooters take a lunch break, they generally retire to a shooting hut. Some of these are rough and ready, while the better examples are often referred to as ‘gin palaces’. Grouse shooting is as much a social occasion as it is a sport, and a lot of local people gain employment from it.

Naturally, walkers must expect some grouse moorlands that are designated access land to be closed at various times. There might be a complete ban on dogs, so check in advance whether this is the case (contact the Open Access Contact Centre, tel 0845 1003298, www.openaccess.naturalengland.org.uk). Moorlands may be closed during the breeding season, and at times when shooting is taking place. Even if a moorland is open, please tread carefully, as grouse eggs are notoriously difficult to spot. If a moorland is open, yet shooting is taking place, then be prepared to wait courteously for a break in the shooting. The shooting season finishes on 10 December, but towards the end there may be very little shooting actually taking place.

Access to the countryside

Many years ago, when faced with the wide-open moorlands of the North Pennines, some walkers simply assumed that they could walk anywhere, while others were more cautious and concerned about the complete lack of rights of way in some areas. The situation over the past few years has been clarified immensely. Rights of way can be followed by anyone, at any time, but there is also a huge amount of designated access land that can be visited by walkers most of the time. The vast military range, the Warcop Training Area, has not been designated access land, and anyone wanting to walk there will find opportunities very limited.

Large areas of open moorland have been designated access land under the Countryside and Rights of Way (CROW) Act 2000. ‘Access land’ should not be regarded as offering unlimited access. Some areas are indeed open all the time, but others are ‘restricted’, and can be closed for various reasons, including grouse shooting and the movement of animals. There may be a complete ban on dogs at any time in some areas, so check in advance whether this is the case. It is always a good idea to check whether any other restrictions or closures are in force – get in touch with the Open Access Contact Centre, tel 0845 1003298, www.openaccess.naturalengland.org.uk. It is likely that notices will be posted at main access points indicating the nature of any closures. Remember that the access granted is on foot only, and does not extend to bicycles or vehicles, nor does it imply any right to camp on a property.

Prominent signs announce ‘access land’ and note any restrictions in force

Getting to the North Pennines

By air

Few visitors to the North Pennines arrive by air. Newcastle Airport, tel 0871 8821121, www.newcastleairport.com, has good connections with the rest of Britain, as well as several European cities. The Metro system links the airport with Newcastle Central Station every few minutes for onward travel. Tees Valley Airport, tel 0871 2242426, www.durhamteesvalleyairport.com, is less well connected, but is also a handy option. Sky Express buses connect the airport with the nearby transport hub of Darlington, allowing rapid connections to the eastern parts of the North Pennines. Leeds Bradford Airport, www.lbia.co.uk, is another option. There are regular Metroconnect buses from the airport to Leeds, enabling a link with the Settle to Carlisle railway line to the Vale of Eden.

By sea

Ferries reach Newcastle from Amsterdam, bringing the North Pennines within easy reach of the Low Countries. Check ferry schedules with DFDS Seaways, tel 0871 5229955, www.dfdsseaways.co.uk. DFDS runs its own buses between the ferryport and Newcastle Central Station for onward travel.

By train

Railways almost encircle the North Pennines, but do not penetrate into the area. Cross Country trains provides direct long-distance rail access to Darlington, Durham and Newcastle from Exeter, Bristol, Birmingham, Edinburgh and Glasgow, www.crosscountrytrains.co.uk. There are also direct Virgins Trains East Coast rail services to Darlington, Durham and Newcastle from London Kings Cross and Edinburgh, www.virgintrainseastcoast.com. Northern trains, www.northernrailway.co.uk, operates along a branch line from Darlington to Bishop Auckland. Carlisle has direct Virgin Trains services from London Euston, www.virgintrains.co.uk. Rail services between Carlisle and Newcastle are operated by Northern Rail, and the same company also runs along the celebrated Settle to Carlisle line through the Vale of Eden, serving Kirkby Stephen, Appleby and Langwathby.

By bus

National Express runs direct services from London Victoria Coach Station to Newcastle and Carlisle, tel 0871 7818181, www.nationalexpress.com. Some long-distance Arriva buses operate to Newcastle, which is one of the hubs in their network, tel 0870 1201088, www.arrivabus.co.uk. Some long-distance Stagecoach buses operate to Carlisle, one of the hubs in their network, www.stagecoachbus.com. JH Coaches offers an interesting, regular cross-country service between Blackpool and Newcastle, www.jhminibreaks.co.uk.

Getting around the North Pennines

The last time a reasonably comprehensive brochure was produced listing most of the useful bus services around the North Pennines was in 2007. There do not seem to be any plans to reintroduce such a publication, which leaves readers the awkward task of tracking down individual timetable leaflets. This is not easy to do, but essential if you are hoping to use public transport to, from, or around places where it is sparse or irregular. Throughout this guidebook, the names of local operators are given so that contact can be made with them. The vast majority of routes in this guidebook were researched using local bus services. See also Appendix B.

By train

Railways do not penetrate the North Pennines. The Weardale Railway operates only between Wolsingham, Frosterley and Stanhope, but has plans to extend its services in future, www.weardale-railway.org.uk. The South Tyne Railway is a very limited narrow-gauge line running only between Alston and Kirkhaugh, but again there are plans to extend the line, www.strps.org.uk.

By bus

While some bus operators make their timetables easy to obtain, others don’t, and there are several operators running a variety of regular and irregular services around the North Pennines. Bear in mind that very few services run from dale to dale, so there is no real ‘network’ allowing easy travel from one place to another. You can always walk!

Stagecoach buses, www.stagecoachbus.com, operates regular services between Carlisle and Newcastle, from Carlisle to Brampton and Alston, and from Kendal to Kirkby Stephen. Most of the East Fellside is sparsely served by Fellrunner buses, tel 01768 88232, www.fellrunnerbus.co.uk. However, the villages near Appleby are served by Robinson’s buses. Grand Prix buses, tel 017683 41328, www.grandprixservices.co.uk, operate between Penrith, Appleby, Brough and Kirkby Stephen. Central Coaches serves Bowes from Barnard Castle, while Hodgson’s buses serves Greta Bridge from Barnard Castle and Richmond. Arriva buses, tel 0870 1201088, www.arrivabus.co.uk, runs most of the buses in Teesdale. Weardale Travel, tel 01388 528235, www.weardale-travel.co.uk, operates throughout Weardale, as well as linking Weardale with Consett and Blanchland. Go North East buses, tel 0190 4205050, www.simplygo.com, serves Consett from Newcastle, as well as operating Tynedale buses serving Allendale from Hexham. Wright Brothers buses, tel 01434 381200, runs local services around Alston, as well as a very important summer service linking Alston with Newcastle, Hexham, Penrith and Keswick. Telfords Coaches, tel 013873 75677, link Nenthead and Alston with Carlisle.

Traveline

Timetable information can be checked for any form of public transport in and around the North Pennines by contacting Traveline, tel 0871 2002233, www.traveline.info. It is also possible to enter start and finish points into Google Maps and be given transport links.

Inside Parkhead Station, which is one of the highest cafés in England, above Stanhope (Walks 34 and 35)

Tourist information and visitor centres

In an area as sparsely populated as the North Pennines, where facilities and services are thinly spread, it can be difficult to obtain information about public transport and accommodation in advance. There are smaller tourist information centres ready and able to assist, but the larger ones are only located in the towns surrounding the area. Inside the North Pennines, there are fewer centres, and they may not be open throughout the year.

Visitor centres usually have specialist themes, assisting with the interpretation of the lead-mining industry, transport and other heritage features, or they may simply be general museums illustrating bygone times. Some of them stock basic tourist information, which can be handy if you are some distance from a tourist information centre. See Appendix B for contact details.

Maps

The map extracts in this guidebook are taken from the Ordnance Survey Landranger series at a scale of 1:50,000. Four sheets cover the North Pennines AONB – 86, 87, 91 and 92. One of the routes strays slightly onto sheet 88. While access land is mentioned on many routes in this guidebook, it is not shown on the map extracts. The full scope and extent of access land in the North Pennines is shown clearly on Ordnance Survey Explorer maps at a scale of 1:25,000. Six sheets cover the North Pennines AONB – OL5, OL19, OL31, OL43, 307 and 315. All these maps can be obtained directly from Ordnance Survey, www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk, or from good booksellers, many outdoor stores and some tourist information offices.

Emergencies

Walkers exploring an area as bleak and remote as the North Pennines need to be self-sufficient. When exploring away from towns and villages, take enough food and drink for your needs, along with a little extra, just in case. If venturing across pathless moorlands, especially in poor visibility, ensure that your map-reading skills are good. Pack a small first aid kit to deal with any cuts and grazes that might be sustained along the way. Hopefully, you will not require anything more, but in the event of a serious injury or exhaustion, it may be necessary to call the emergency services.

The mountain rescue, police, ambulance or fire brigade are all alerted by dialling 999 (or the European 112). Be ready to supply full details of the nature of the emergency, so that an appropriate response can be made. Keep in contact with the emergency services in case they require further information or clarification.

The Pennine Way national trail has introduced many walkers to the wildest parts of the North Pennines (Walk 25)

Using this guide

This guidebook contains details of 50 walking routes, spread over all parts of the North Pennines. Most are circular, so that anyone using a car can return to it at the end of the walk, but a few are linear and require the use of public transport for completion. Together, these routes stretch nearly 800km (500 miles) across immensely rich and varied countryside, taking in some of the finest and most interesting features of the region. The route summary table in Appendix A is provided to help you choose the right routes for you and your party.

Read the route descriptions carefully before setting out, and if carrying Ordnance Survey maps in addition to the extracts used in this book, be sure to take the ones listed for each walk. The essential information for each route is given under the following headings.

Start/Finish: usually the same place, but sometimes different

Distance: given in kilometres and miles

Terrain: summary of the nature of the terrain and paths used

Maps: OS Landranger and OS Explorer sheet numbers

Refreshments: summary of pubs and cafés on the route

Transport: basic bus frequency and destinations.