Читать книгу The North York Moors - Paddy Dillon - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

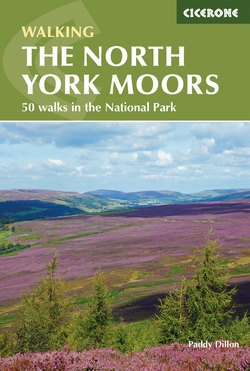

This guidebook offers 50 walks in the varied landscape of the North York Moors National Park. The park was designated in 1952 and covers 1432km2 (553 square miles) of land, comprising the largest continuous expanse of heather moorland in England. The moors are of no great height yet offer a wonderful sense of spaciousness, with extensive views under a ‘big sky’. There are also deep verdant dales where charming scenes and hoary stone buildings can be found, as well as a remarkable cliff coastline designated as the North Yorkshire and Cleveland Heritage Coast. The long-distance Cleveland Way wraps itself around the moors and coast, but there are many other walks that explore the rich variety of the area, focusing on its charm, history, heritage and wildlife.

The walks are distributed through seven regions within the park, enabling walkers to discover and appreciate the Tabular Hills, Hambleton Hills, Cleveland Hills, Northern Moors, High Moors, Eastern Moors and Cleveland Coast. For those who like a challenge, the course of the classic Lyke Wake Walk, crossing the national park from east to west, is also offered, split over a four-day period to allow a leisurely appreciation of the moors. Almost 725km (450 miles) of walking routes are described here, although the national park could furnish you with many more splendid ones from a stock of 1770km (1100 miles) of public footpaths and bridleways.

People have crossed the North York Moors since time immemorial, and some of their routes survive to this day. Stout stone crosses were planted to assist travellers and traders with a safe passage, and these days practically all rights of way are signposted and walkable, although some routes are used far more than others.

Despite having the appearance of a wilderness, this area has often been, and remains to this day, a working landscape. The moors are scarred and quarried in places by man’s search for mineral resources, and the heather cover requires year-round management for the sport of grouse shooting. Walkers with enquiring minds will quickly realise that the human history and settlement of the moors, even at its highest points, stretches back over thousands of years. Our own enjoyment of the moors, in contrast, may be nothing more than a transient pleasure.

Walkers follow an old railway trackbed above Rosedale (Walk 30)

Brief history of the moors

Early settlement

The first people to roam across the North York Moors were Mesolithic nomads, eking out an existence as hunter-gatherers some 10,000 years ago. Swampy lowlands surrounded the uplands, and apart from a few flakes of flint these people left little trace of their existence. Evidence of the Neolithic settlers who followed can be seen in the mounds of stones they heaped over their burial sites, called barrows, which date back to 2000BC. Soon afterwards, from 1800BC onwards, the Beaker People and Bronze Age invaders moved into the area. They used more advanced methods of land clearance and tillage, and buried their dead in conspicuous mounds known as ‘howes’. These people exhausted the land, clearing too much forest too quickly. Minerals leached from the thin soils, so that the uplands became unproductive. Climate changes led to ground becoming waterlogged and mossy, so that tillage became impossible and scrub moorland developed. Iron Age people faced more of a struggle to survive and had to organise themselves in defensive promontory forts. Perhaps some of the linear dykes that cut across the countryside date from that time, although many structures are difficult to date with any degree of certainty.

Roman settlement

The Romans marched through Britain during the first century and founded a city at York. Perhaps the most important site on the North York Moors was Cawthorn Camp near Cropton, which was used as a military training ground. Although Wade’s Causeway in Wheeldale is often referred to as a Roman road, it may not be. Hadrian’s Wall kept the Picts at bay to the north, but the east coast was open to invasion by the Saxons, so the Romans built coastal signal stations in AD368 at Hartlepool, Hunt Cliff, Boulby, Goldsborough, Whitby, Ravenscar, Scarborough, Filey and Flamborough Head. Some of these sites have been lost as the cliffs have receded. By AD410 the Romans had left Britain, and the coast was clear for wave upon wave of invasions.

Dark Age settlement

Saxons, Angles, Danes and other invaders left their mark on the North York Moors, establishing little villages and tilling the land, mostly in the dales, as the higher ground had long since reverted to scrub. Many of these settlers were Christian, and in AD657 a monastery in the Celtic Christian tradition was founded at Whitby. Whitby Abbey was notable for one of its early lay brothers, Caedmon, who was inspired to sing, and whose words comprise the earliest written English Christian verse. During the successive waves of invasion there were times of strife, and the abbey was destroyed in AD867. Other small-scale rural monastic sites are known. Many early Christian churches were simple wooden buildings. Some of the earliest carved stone crosses date from the 10th century.

Lilla Cross is the oldest Christian monument on the moors (Walk 40)

Norman settlement

A more comprehensive invasion was mounted by the Normans, who swept through the region during the 11th century. They totally reorganised society, establishing the feudal system and leaving an invaluable insight into the state of the countryside through the vast numbers of settlements and properties listed in the Domesday Book. In return for allegiance to the king, noblemen were handed vast tracts of countryside and authority over its inhabitants. Resentment and violence was rife for a time, and the new overlords were obliged to build robust castles. Many noblemen gifted large parts of their estates to religious orders from mainland Europe, encouraging them to settle in the area.

Monastic settlement

Monasteries and abbeys were founded in and around the North York Moors in the wake of the Norman invasion, and ruins dating from the 12th and 13th centuries still dominate the countryside. Stone quarrying was important at this time, and large-scale sheep rearing was developed, leading to the large, close-cropped pastures that feature in the dales. There were still plenty of woodlands for timber and hunting, but the moors remained bleak and barren and were reckoned to be of little worth. Early maps and descriptions by travellers simply dismissed the area as ‘black-a-moor’, yet it was necessary for people to cross the moors if only to get from place to place, and so a network of paths developed. The monasteries planted some of the old stone crosses on the moors to provide guidance to travellers. This era came to a sudden close with Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries in the 16th century.

Recent settlement

Over the past few centuries the settlement of the North York Moors has been influenced by its mineral wealth and the burgeoning tourist industry. At the beginning of the 17th century an amazing chemical industry developed to extract highly prized alum from a particular type of of shale. This industry lasted two and a half centuries and had a huge impact around the cliff-bound fringes of the North York Moors. From the mid-18th to mid-19th centuries, Whitby’s fishing industry specialised in whaling, and the town benefitted greatly. The 19th century was the peak period for jet production, often referred to as Whitby Jet. Railways were built in and around the North York Moors throughout the 19th century, bringing an increase in trade and allowing easier shipment of ironstone from the moors. Railways also laid the foundation for a brisk tourist trade, injecting new life into coastal resorts whose trade and fishing fleets were on the wane. Tourism continues to be one of the most important industries in the area, and tourism in the countryside is very much dependent on walking.

Whitby and Whitby Abbey as seen from the Whalebone Arch (Walk 44)

North York Moors industries

Alum

Throughout the North York Moors National Park huge piles of flaky pink shale have been dumped on the landscape, sometimes along the western fringes of the Cleveland Hills, but more especially along the coast. These are the remains of a large-scale chemical industry that thrived from 1600 to 1870. The hard-won prize was alum: a salt that could be extracted from certain beds of shale through a time-consuming process.

Wherever the shale occurred, it was extensively quarried. Millions of tons were cut, changing the shape of the landscape, especially along the coast. Wood, and in later years coal, was layered with the shale, and huge piles were set on fire and kept burning for months, sometimes even a whole year. The burnt shale was then soaked in huge tanks of water, a process known as leaching. Afterwards, the water was drawn off and boiled, which required more wood and coal, as well as being treated with such odious substances as human urine, brought from as far away as London. As crystals of precious alum began to form, the process was completed with a purification stage before the end product was packed for dispatch.

Alum had many uses but was chiefly in demand as a fixative for dyes, as it promoted deep colours on cloth, which became colour-fast after washing. The Italians had a virtual monopoly on the trade until the alum shale of Yorkshire was exploited from 1600. However, the local industry went into a sudden decline when other sources of alum, and more advanced dyestuffs, were discovered from 1850. The long and involved process of quarrying, burning, leaching, boiling, crystallising and purifying was replaced by simpler, cheaper and faster production methods. Two dozen sites are scattered across the landscape where the industry once flourished. Look upon these stark remains, consider the toil and labour and bear in mind that it all took place so that fine ladies and gentlemen could wear brightly coloured clothes!

Jet

Jet, often known as Whitby jet, has been used to create ornaments and jewellery since the Bronze Age. It is found around the North York Moors, often along the coast, but also far inland around Carlton Bank. Jet is a type of coal, but it is peculiar because it formed from isolated logs of driftwood rather than from the thick masses of decayed vegetation that form regular coal seams. High-quality jet is tough and black, can be turned on a lathe or carved and takes a high polish. Jet has been used to create everything from intricately carved statuettes to shiny beads and facetted stones for jewellery. Jet crafting has long centred on Whitby, with peak production years being in the 19th century.

Ironstone

Cleveland ironstone was mined and quarried from around 500BC, as evidenced by an ancient bloomery site (where malleable iron is produced directly from iron ore) on Levisham Moor. Large-scale working didn’t commence until around 1850, when coastal and moorland locations, such as Skinningrove and Rosedale, were exploited. As the steelworks developed, the tiny coastal village of Skinningrove became known as the Iron Valley. Ironstone from Rosedale was transported over the moors by rail to the blast furnaces in Middlesbrough. Huge quantities of coal had to be shipped to the area, as industry and commerce were hungry for the iron that was produced. The last local ironstone mine, at North Skelton, closed in 1964. The number of steelworks in Middlesbrough has greatly reduced, while Skinningrove only just manages to remain in production.

The Rosedale Ironstone Railway seen at the top of Rosedale Chimney Bank (Walk 30)

Fishing and whaling

The coastal towns and villages thrived on fishing, especially herring fishing, until stocks dwindled. In Whitby, mainly from the mid-18th to mid-19th centuries, the fishing fleets turned their attention to whaling. Whalers often spent months at sea and didn’t always return with a catch, but when they did, regular catches would bring great wealth to the town. Whale blubber was rendered for its oil, which was highly prized because when it burned it gave a bright and fairly soot-free light. Whenever the fishing settlements fell on hard times, smuggling provided an alternative form of employment, most notably at Robin Hood’s Bay.

Grouse shooting

Some visitors imagine that the moors have always been there and represent the true wilderness qualities of the area, but this is untrue. The moors have been man-managed over a long period of time and will only continue to exist with year-round maintenance. The uniform heather moorlands are largely a 19th-century creation, managed entirely for the sport of grouse shooting.

The red grouse, essentially a British bird, is tied to the heather moorlands on which it depends for food and shelter. Walkers know it for its heart-stopping habit of breaking cover from beneath their feet, then flying low while calling, ‘go back, go back, go back’. It is a wonderfully camouflaged bird, spending all its time in the heather. Grouse graze on young heather shoots but need deep heather for shelter. Natural moorlands present a mosaic of vegetation types, but as the sport of grouse shooting developed in the 19th century, it became clear that a uniform heather habitat, which favours the grouse above all other species, would result in much greater numbers of birds to shoot.

Moorland management required vegetation to be burnt periodically, and as heather seeds are more fire-resistant than other seeds, heather cover quickly became dominant. Drainage ditches were also dug to dry out boggy ground and encourage further heather growth. Heather was burnt and regrown in rotation to provide short heather for feeding and deep ‘leggy’ heather for shelter. Gamekeepers were employed to shoot or trap ‘vermin’, so that grouse could flourish free of predators; however, it remains difficult to control intestinal parasites that often result in the birds being in poor condition. Harsh winters and cold wet springs can also cause devastating losses among the grouse population. What’s more, old paths used by shooting parties have been widened for vehicular use, sometimes rather insensitively.

Come the Glorious Twelfth, or 12 August, the grouse-shooting season opens with teams of beaters driving the grouse towards the shooters, who station themselves behind shooting butts. Some moorlands charge very high prices for a day’s shooting, and shoots are very much a social occasion. Walkers who despise blood sports should, nevertheless, bear in mind that without grouse shooting the moors would not be managed and would revert to scrub. A lot of moorland has been lost to forestry and agriculture, and managing the moors for shooting prevents further loss. What remains today is England’s greatest unbroken expanse of heather moorland, and most visitors are keen to see it preserved.

Boulder-studded heather on the lower slopes of Easterside Hill (Walk 10)

North York Moors today

The North York Moors National Park Authority maintains an up-to-date website full of current contact information, events information and a comprehensive wealth of notes that go well beyond the scope of this guidebook. Be sure to check it in advance of any visit at www.northyorkmoors.org.uk

Getting to the North York Moors

By air and sea

The nearest practical airports to the North York Moors are Leeds/Bradford and Teeside, although good rail connections allow ready access from the London airports and Manchester Airport. The nearest practical ferry ports are Hull and Newcastle.

By rail

Good rail connections from around the country serve the busy tourist resort of Scarborough throughout the day. To a lesser extent, Whitby can be reached by direct rail services from Middlesbrough, which would suit most travellers from the north-east. Other railway stations to consider include Malton, on account of its summer weekend Moorsbus services, and Saltburn, which connects with regular Arriva bus services. Check the National Rail website to plan journeys to and from the area, www.nationalrail.co.uk tel 03457 484950.

By bus

Daily National Express buses run to Scarborough and Whitby – www.nationalexpress.com. Daily Yorkshire Coastliner buses run from Leeds and York to Scarborough and Whitby – www.yorkbus.co.uk. Daily Arriva bus services from the north-east run to Guisborough, Whitby and Scarborough – www.arrivabus.co.uk/north-east. Daily East Yorkshire Motor Services buses run from Hull and the surrounding area to Scarborough – www.eyms.co.uk.

Getting around the North York Moors

Moorsbus

The Moorsbus is a network of special low-cost bus services, often tying in with other bus and rail services to link some of the more popular little towns and villages with some of the more remote parts of the national park. Walkers who wish to make use of Moorsbus services should obtain a current timetable either from the national park authority or from tourist information centres. Timetables and places served tend to change each year, but as a general rule, services operate on summer Fridays, Saturdays, Sundays and Bank Holiday Mondays. It is essential to obtain up-to-date information, starting with the Moorsbus website, www.moorsbus.org

Moorsbus services link the towns with dales and remote moors

Buses

Other bus services are also available in the national park. Arriva buses run excellent regular daily services around the northern part of the North York Moors, as well as along the coast from Staithes to Whitby and Scarborough – www.arrivabus.co.uk/north-east. Scarborough & District buses cover the southern parts of the North York Moors, between Scarborough and Helmsley, and along the coast from Scarborough to Ravenscar, www.eyms.co.uk. Other operators include Transdev, which serves Helmsley from York, www.yorkbus.co.uk; Abbotts, which serves Osmotherley and Stokesley, www.abbottscoaches.co.uk; and Ryecat, which provides community transport to villages in the south of the national park, ryedalect.org.

Rail

Following the closure of the coastal line in 1965, rail services have drastically reduced in the North York Moors. However, daily Northern trains run along the Eskdale line from Middlesbrough to Whitby, providing access to a series of fine walks in the northern part of the national park, www.northernrailway.co.uk. Seasonal steam-hauled services on the North Yorkshire Moors Railway, between Pickering and Goathland, catch the attention of walkers who want to enjoy a nostalgic railway journey to their walks, www.nymr.co.uk. All was not lost with the closure of the coastal railway, since the entire line between Scarborough and Whitby is now part of the National Cycle Route 1.

The North Yorkshire Moors Railway provides nostalgic steam-hauled services

Accommodation

Accommodation options around the North York Moors National Park are abundant, but bear in mind that during the peak summer season it can still be difficult to secure lodgings, and in the depths of winter some places are not open. At the budget end there are plenty of campsites, although youth hostels are rather thin on the ground. Following closures in recent years there is now only Whitby, Boggle Hole, Scarborough, Lockton, Helmsley and Osmotherley.

Walkers looking for B&B, guest house or hotel accommodation will find plenty of choice in some areas, especially the coastal resorts, but little or nothing in some of the less-frequented dales further inland. However, every standard is available, from homely B&Bs and basic farmhouse accommodation, to luxury hotels with every facility and full meals services. On the whole, serviced accommodation in the North York Moors tends to be a little pricey, but with careful research reasonably priced options can be found, especially with Airbnb, www.airbnb.co.uk. The tourist information centres at Scarborough and Whitby may be aware of last-minute vacancies during busy periods.

Food and drink

Most of the walking routes in this guidebook start and finish at places where food and drink is available. The starting point may be a town with plenty of pubs, restaurants and cafés, or it may be a village with a pub and a tearoom. There may be places en route that offer food and drink, such as wayside pubs and cafés, or there may be nothing at all. A note about the availability of refreshments is given in the information box at the beginning of each walk, although there is no guarantee that the places will be open when you need them! When booking accommodation be sure to enquire about meals, or to let your hosts know if you have any special dietary requirements. It goes without saying that you should be self-sufficient for food and drink for the duration of your walks.

When to walk

Most visitors – and indeed too many visitors – explore the North York Moors during the summer months, and when the moors are flushed purple with heather and the air is sweetened with its scent, this can be a delightful time. But be warned that when the sun beats down on the moors there may be little shade, and the longer a heatwave lasts, the more the air tends to turn hazy, so that colour and depth are lost from the views. The spring and autumn months offer good walking conditions, with plenty of cool, clear days – often cool enough to ensure that you keep striding briskly! There is also less pressure on accommodation and easier access to attractions along the way. In the winter months accommodation and transport are much reduced, and foul weather can sweep across the moors, which offer little shelter from wind or rain. However, there can be some exceptionally bright, clear days, and a dusting of snow on the landscape transforms the scene into something quite magical.

The heathery expanse of Spaunton Moor from above Lastingham (Walk 29)

Maps of the routes

Extracts from the Ordnance Survey Landranger series of maps, at a scale of 1:50 000, are used throughout this guidebook, with overlays showing the routes. These extracts are adequate for navigation on the walks, but if you wish to explore more of the countryside off-route, and want to see exactly where you are in relation to other walking routes, then obtain the appropriate Ordnance Survey maps. The Landranger maps covering the North York Moors National Park include sheets 93, 94, 99, 100 and 101. Greater detail and clarity are available on Ordnance Survey Explorer maps, at a scale of 1:25 000. The relevant Explorer maps are OL26, covering the western half of the national park, and OL27, covering the eastern half of the national park. Bear in mind that these maps are printed on both sides, so that each sheet has a North and South side. The relevant Ordnance Survey maps for each walk are quoted in the information box introducing the walk. The starting points for the walks can be pinpointed using the six-figure Ordnance Survey grid references supplied. The BMC/Harvey map of the North York Moors covers all but six of the routes in this guidebook.

Access to the countryside

Use up-to-date maps, as dozens of rights of way have been officially diverted over the years, often to avoid farmyards or fields of crops. On the high moors walkers who are good map-readers will frequently notice that the clear path or track they are following is not actually a right of way, and that the right of way shown on the map is quite untrodden on the ground! For the most part, walkers are voting with their feet and have done so for many years, and landowners seem to accept the situation.

Large areas of open moorland have been designated as open access land under the Countryside and Rights of Way (CRoW) Act 2000. Open access land should not be regarded as offering unlimited access. Some areas are indeed open at all times, but others are restricted and can be closed for various reasons, including grouse shooting and the movement of animals. In some areas there may be a complete ban on dogs at any time, or it might be a requirement for dogs to be kept on a lead, particularly in areas where ground-nesting birds are present. It is a good idea to check whether any restrictions or closures are in force, which can be advised by the Open Access Contact Centre, tel 0300 0602091. Remember that access is granted on foot only and doesn’t extend to bicycles or vehicles, nor does it imply any right to camp on a property. Also, remember that access to the area surrounding RAF Fylingdales is strictly forbidden.

National park visitor centres

There are two national park visitor centres in the North York Moors, and they perform the very important function of trying to interest visitors in and educate them about the necessary balance that needs to be struck between conservation and recreation in this fragile upland area. The busier of the two centres is beside the main road at the top of Sutton Bank, the quieter one is outside the little village of Danby in Eskdale. Both centres are full of information, dispensing maps, guidebooks and leaflets that cover walking opportunities, as well as presenting the history, heritage and natural history of the area. Audio-visual presentations are available, as well as guided walks with national park rangers. Both centres can be reached by Moorsbus services that operate at weekends during the summer.

Sutton Bank National Park Centre, tel 01845 597426

The Moors National Park Centre, Danby, tel 01439 772737

For administrative enquiries contact: North York Moors National Park Authority, The Old Vicarage, Bondgate, Helmsley, York, YO62 5BP, tel 01439 772700 www.northyorkmoors.org.uk.

Ralph Cross is an ancient moorland marker and serves as the national park logo

Tourist information centres

The main tourist information centres are on the coast at Scarborough and Whitby. These centres can help with various enquiries, including accommodation, attractions and transport.

Town Hall, Nicholas Street, Scarborough, YO11 2HG, tel 01723 383636 www.discoveryorkshirecoast.com

Langbourne Road, Whitby, YO21 1DN, tel 01723 383636 www.discoveryorkshirecoast.com

Emergency services

No matter the nature of the emergency, if you require the police, ambulance, fire service, mountain rescue or coastguard, the number to dial is 999 (or European number 112). Be ready to give a full account of the nature of the emergency, and give your own phone number, so that they can stay in contact with you. Callers cannot request helicopter assistance, but based on the information supplied, someone will decide if one is needed. Always carry a basic first-aid kit to deal with minor incidents, be self-sufficient in terms of food and drink and dress in or pack the appropriate clothing to cope with all weather conditions. Those venturing on to exposed moorlands need the experience and skills to cope in such an environment, as well as the common sense to turn back if things get difficult or dangerous. Think about your actions and aim to walk safely.

Using this guide

This guidebook contains details of 50 walking routes, spread all around the North York Moors National Park. Most are circular, so that anyone using a car can return to their vehicle at the end of the walk; however, a few are linear and require the use of public transport to complete them. Together, these routes cover almost 725km (450 miles) of rich and varied countryside, taking in some of the finest and most interesting features on and near the moors. The route summary table in Appendix A is provided to help you choose between the different routes.

Read the route descriptions carefully before setting out, and if carrying Ordnance Survey maps in addition to the extracts used in this book, be sure to take the ones listed for each walk. The essential information for each route is presented under standard headings.

Start/Finish: usually the same place, but sometimes different.

Distance/Ascent/Descent: given in kilometres, miles, metres and feet.

Time: duration of the walk, but not including time spent resting, eating, etc.

Terrain: summary of the nature of the terrain and the paths used.

Maps: OS Landranger and OS Explorer sheet numbers.

Refreshment: summary of pubs, restaurants and tearooms on the route.

Transport: summary of the available buses and/or trains serving the route.

GPX tracks

GPX tracks for the routes in this guidebook are available to download free at www.cicerone.co.uk/951/GPX. A GPS device is an excellent aid to navigation, but you should also carry a map and compass and know how to use them. GPX files are provided in good faith, but neither the author nor the publisher accepts responsibility for their accuracy.

The ‘Surprise View’ at Gillamoor stretches across Farndale to Spaunton Moor (Walk 7)