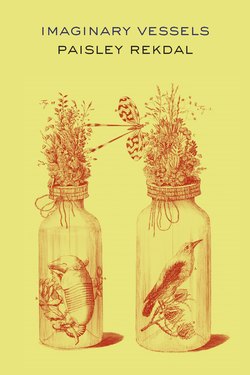

Читать книгу Imaginary Vessels - Paisley Rekdal - Страница 9

ОглавлениеBUBBLES

The child purses his lips around a hole. Blows

and out the radiant world swells forth.

The park swings bend. His mother’s face shrinks

to the size of a bubble. I sit across from them,

on my separate bench, bobbing past in its reflection.

It’s my gift, this vial of soap.

I bow my dark head low as my friend’s son

pats my cheeks in thanks, obediently

sucks in another breath

and blows.

“Any fool can make soap;

it takes a clever man to sell it.”

So Thomas Barratt, 1880, said, and pursued Millais

to paint Pears’ advertising: an English painter

for an English soap. “Of two countries

with an equal weight of population,” he wrote,

“the most highly civilized will consume

the greatest weight of soap.” A quote

from my scholar friend in her book

on bubbles that she’s given me: my gift

of this toy a nod to her descriptions

of palm oils rendered in chains

of vats, thickened with the meat

of African coconuts.

Through a stream of bubbles,

I watch her wipe her son’s streaked face, recall

my washing machine at home which has a setting

labeled Baby Clothes. The store model

wore a pink-and-blue sign reading,

Don’t You Want One? I think

of the painting on her book’s cover, Newton’s

Discovery of the Refraction of Light: a thin-faced scientist slumped

in dark, while his nephew, by a bank of windows,

blows bubbles. On Newton’s side of the canvas:

a dusty globe, a world of shadows

that dissolves beside the child

in play, revealing how the sun refracts the panes

the maid will have to scrub. In the image,

she turns her head away, the sun

begun to bore into her eyes. And here’s a bore of sun

illuminating the bubble’s flaw that stuns the child

now blowing in the park, learning the tensile skins

can’t withstand the pressure

of a touch. “They don’t last!” he shrieks

as his mother hugs him, a squalling

aggregate of cells neither of us can hush. Of cells,

I also thought an aggravate. “Make this the sweetest

picture postcard yet,” Barratt begged Millais. And so

the painter drew a Pre-Raphaelite child at play

blinking at the globe he’s made, a lens of clean in which

the thin white etch of him sails past

in dark, the milk-white cheek, the booted

foot: the boy’s blue eyes turned in rapture to what

a parent’s invention makes. A Child’s World,

Millais titled it, but Barratt

stuck a bar of Pears in it and turned

the painting into posters, puzzles, postcards

shipped along with images of English flags

and Maori girls, kaleidoscopic

slow flash photos of bursting

bullets, their shock waves caught and used to improve

British rifle manufacturing.

“We have a perfect right

to take toys and make them into philosophy,”

my friend’s book quotes. “Inasmuch as we have turned

philosophy into toys.”

Look: a bubble of black

wobbles and bursts: explodes the world

to a slick of oil.

The clouds pull back. The boy, damp faced from his fit,

now sleeps. Sunlight holds, refracts him in his nap

as something in my friend’s face

cracks. It wildly opens.

Don’t you want one? something whispers. Don’t you, really?

Last night’s thinnest edge

of dream still wavers, the one where the doctor tells me

I am carrying, but will not tell me what

or when. Black hope rises,

bursts inside me. “It’s an aggravate of sells,” he says—

The world grows thin. My friend packs up the toys and kit,

tapping at her soapy vial.

She shakes up the foam and sticks in the pipe.

A world blows up.

The mother and child float by in it.