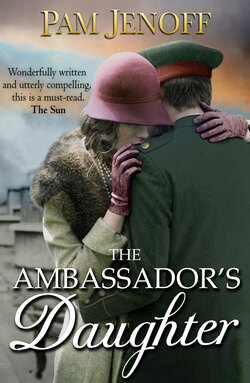

Читать книгу The Ambassador's Daughter - Pam Jenoff - Страница 12

3

ОглавлениеI sit in the stillness of the study, the room dim but for the pale light that filters in, silhouetting the windowpane. Beyond the lattice of dark wood, the robin’s-egg-blue sky is laced with soft white clouds. A rolling wave of slate-gray domes and spires spills endlessly across the horizon, poking out from the haze that shrouds the city like a wreath. Bells chime unseen in the distance.

I wrap my hands around the too-hot cup of tea that sits before me on the table, then release it again and gaze down at the front page of yesterday’s Le Journal. The early mornings have always been mine. Papa loves to work long into the night, a lone lamp at the desk pooling yellow on the papers below. As a child, I often fell asleep to the sweet smell of pipe smoke, the sound of his pen scratching on the paper a familiar lullaby.

I eye the letter I’d started writing to Stefan the previous evening. I had written to him regularly when we were in En gland, of course. But I have not put pen to paper since our arrival in Paris simply because I did not know what to say about the fact that I had come here instead of going home.

I reread my words. I attended the welcome reception for Wilson and it was quite the affair … I crumple the piece of paper and throw it in the wastebasket. I feel foolish talking of parties and Paris while he lies wounded in a hospital bed. Why had I not returned to Berlin straightaway to be with him? Stefan is so loyal. Once, when I was laid up with a sprained ankle, he faithfully brought me my school assignments each afternoon and carried my completed work back to school each morning for a week. He would not have left me alone if the situation was reversed. I am not abandoning him, though. I will go back as soon as the conference is over.

Starting on a fresh sheet of crisp stationery, I decide to be more forthright: I’m sorry not to be there with you. Papa was summoned to the conference and I did not want him to travel alone. Then I pause. Stefan has never begrudged me my relationship with my father, the way that Papa seemed to come first and would always be central in our lives. But he would know that Papa had Celia here to look after him. I try again: Papa had to come directly to Paris and did not want me to travel back to Germany alone. Though the explanation is still unsatisfactory, I set down my pen.

I stand and pick up Papa’s hat from the chair. Wrapped up in his thoughts, he’s prone to dropping things and leaving them where they fall. I run my hand along the felt brim, too wide to be fashionable now. With love, Lucy, reads the now-faded embroidery along the inside band. It was a gift from my mother, worn beyond repair.

Reflexively, I continue straightening the room, moving books to piles in the corners, sweeping a few missed crumbs from the table. We’ve managed to accumulate a sizable bit of clutter, even in the short time we’ve been here. There are a handful of cozy touches—a small vase of gardenias on the windowsill, a throw across the settee—all courtesy of Tante Celia, who is domestic in a way that I could never be.

In the corner are the discarded boxes that had contained Uncle Walter’s Hanukah presents. The holidays had passed quietly, Papa so immersed in work before the formal opening of the conference he had scarcely paused. Too much celebrating would have been unseemly, anyway, with all of the suffering, the homeless and wounded that linger at every corner. But Uncle Walter, unaware of the subtle context here, had sent boxes of gifts: slippers and a wrap for me, new ties and shirtwaists for Papa. He’d sent money, too, more than we had seen in some time, with special instructions that I was to have my wedding gown made. Included was a remnant of lace and a picture of my mother’s dress for the tailor to copy.

Picking up the lace now, my throat tightens. The gift contains a silent message—that I am to do what is expected of me, play along as I always have. This time in Paris is not a license to step out of line, but merely a brief sojourn before I marry Stefan.

Stefan had proposed the Sunday after the war broke out on a walk by the lake behind the villa. “If you’ll marry me when I get back …”

I hesitated. Stefan and I had been formally courting for just over a year, the transition from friendship to romance marked rather unceremoniously by a brief conversation between him and Papa. Yet despite the exclusivity of our relationship and the time that had passed, I hadn’t given thought to the future. But the war had sped up the film, bringing the question to the glaring light of day. “Why rush things?”

His eyes widened with disbelief. “I’m going to war, Margot.” For the first time then I saw real fear, portending all that was to come.

“I know. But they say it will be quick—weeks, maybe a month or two at worst case. Then you’ll be back and we’ll decide things properly.” He did not answer but continued staring at me, pleading. I swallowed. Marriage felt so adult and constraining, so permanent. Stefan asked little of me, but he was asking for this now.

I thought of the dance Stefan and I had attended months earlier. At first it had been an awkward affair—most students had not come as couples and boys and girls lingered separately back against the walls, barely speaking. Then a few people shuffled to the middle of the dance floor and gradually others joined them. I had gazed at Stefan hopefully and, seemingly encouraged, he extended his hand. But before he could speak, Helmut, a thick-necked boy, walked over. “Would you like to dance?” he asked me, so forcefully it was hardly a question. I looked up at Stefan helplessly—I had come with him and I wanted to dance with him, at least for the first song. But he shrugged, unwilling to struggle. If Stefan could not stand up for himself at a dance, how would he ever survive war? He needed the promise of our marriage to keep him strong.

The war was coming, I told myself; we would all need to make sacrifices. “Well, then,” I said. Marriage was to be my own personal conscription. “Yes, I would love to be your wife.”

We walked back to the house to share the good news. “You don’t mind, do you, that he didn’t have time to ask permission?” I asked Papa. “I mean, with the war and all.”

“He had asked my permission some time ago,” Papa confided. So Stefan had this planned all along. The war had just been an excuse to move things up.

The quiet clicking of the door leading from Papa’s room into the hallway stirs me from my thoughts. Tante Celia keeps her own apartment in a town house in the 16th arrondissement that I’ve not visited, a fiction designed for public appearances as well as for my benefit. Once, when I was not more than twelve, I spied her leaving our house in Berlin before dawn, head low beneath the hood of her cloak. At the time I was incensed: How dare they soil the memory of my mother—how dare he? Older now, I do not begrudge Papa company and warmth. He seems so much happier with her nearby than he had been in England, where Celia could not get a visa to join us. She is just so plain and uninteresting, a shadow of her beautiful older sister. Though perhaps that is why Papa likes her—she is the closest reminder of my mother.

My gaze travels to the photograph of the tall, willowy woman on the mantelpiece, taken in our Berlin garden before I was born. My mother had been an actress before marrying my father, leaving home at the age of sixteen and performing around the world to great acclaim against her family’s wishes. Papa had seen her in a performance of As You Like It in Amsterdam and had been so taken with her portrayal of Rosalind that he had sent flowers backstage with an invitation to dinner. Six months later they wed and she left the stage for good.

I study the photo, which Papa brings with him wherever we go and puts out as soon as we arrive. Her pose, one hand on hip, the other outstretched slightly with palm upward, is beguiling, yet somehow natural. Mother and I shared the same pale skin and almond-shaped eyes, but her dark hair was smooth, not kinked and unruly like mine. Ten years have passed, and my actual memories of our time together are dim. To me, she is a shadowy figure with a sad expression and hollow eyes, a woman who never seemed to sit still or truly be present.

I return to my chair and wrap my hands around the warm cup of tea, watching as a flock of starlings rises from one of the cathedral spires, startled by a noise I did not hear. My thoughts turn to Krysia. It has been weeks since she put me in the taxi. I had hoped she might call or send word inviting me out to join her circle of friends again. The longing for company is strange to me. I’ve never had female friends. Even in school, I tended to play with the boys, enjoying the pure physicality of sport where it was permitted. But the excitement of the evening I spent at the bar with Krysia has left me hoping to see her again.

She has not contacted me, though. Did I embarrass her with my lack of substance? A few nights earlier there was a gala and I attended more eagerly than usual, urging Papa to dress promptly. But a string orchestra played waltzes, the piano in the corner deserted and silent.

Restless, I finish my tea and dress, then scribble a note for Papa before putting on my coat and gloves and leaving the apartment. On the street, I pause. It is January now, the pavement altogether too icy for biking, so I begin to walk, making my way toward the river. As I near the wide expanse of water, the wind, no longer buttressed by the buildings, blows sharply. Drawing my coat tight, I cross the arched pont de la Concorde. On the far bank sits the wide expanse of the Quai d’Orsay. Though it is not yet seven o’clock, the crowds of demonstrators, protesting for their causes and seeking to be heard, have already begun to form outside the tall iron gates of the foreign ministry where Wilson and the other powers labor to re-create the world.

I press forward, head low against the wind. Past the ministry and away from the water now, the streets begin to narrow. At the corner I pause, peering uneasily down a side street. Rue de Courty is one that I have avoided for months. The center of the block is taken up by a wide building with columns that suggest it was once a government administration building of some sort. I passed it once shortly after our arrival in Paris, taken aback by the improbably young men in wheelchairs, who sat forlornly by the windows looking as though they are just acting parts in a play and in fact might jump up and walk at any second. Would they ever leave the hospital? What if there were no families to claim them? I had run from the block, haunted.

Now my guilt rises anew: Should I have gone back to Berlin and taken Stefan from the hospital, cared for him myself? The hospitals themselves could be as dangerous as war—nursing care was short and supplies minimal even in the best hospitals. Influenza and tuberculosis were rampant.

If I went back to Germany now, perhaps I could get him out.

Unable to bear the cold any longer, I walk to the corner and hail a taxi. “Montparnasse,” I say to the driver and it is only then that I fully realize I am going to try to find Krysia. “Rue Vavin,” I add, recalling one of the major intersections. A few minutes later, I pay the driver and step out onto the pavement. The boulevard du Montparnasse is quiet at this early hour, the bars and cafés that seem to never sleep now briefly at rest. At La Closerie des Lilas, I peer through the glass into the darkened café. I push against the door expecting it to be locked, but it opens.

“Bonjour.”

“Oui?” I step inside, adjusting my eyes to the dim lighting. Ignatz is behind the counter, alone in the otherwise deserted room. Last time I was here the café felt almost magical, but in the crude light of day it is a dirty room, trash from the previous evening still littering the floor, ordinary in a way that makes me wonder if I imagined the revelry of the earlier night. “Ah, the ambassador’s daughter.” His tone is mocking.

I consider pointing out that the title more aptly describes Krysia than me, then decide against it. “Margot Rosenthal,” I correct.

“Mademoiselle Rosenthal.” He gives a mock bow, then throws a handful of spoons into one of the bins with a clatter. “Of course. How can I help you?” His voice is gravelly.

“Krysia … that is, I haven’t heard from her in a few weeks and I was worried.”

“I haven’t seen her. She’s sick. The grippe, or some such thing.”

So that is why she hasn’t contacted me. I’m relieved and concerned at the same time. “Is it serious?”

He shrugs. “I shouldn’t think so, or I would have heard. She’s got Marcin to look after her.”

His answer does little to assuage my fear. “I’d like to check on her if you’d be so kind as to provide her address.”

I hold my breath, expecting him to object, but he pulls out a scrap of paper and scribbles on it. “It’s not far from here. If you walk up rue d’Assas, you’ll find it just before you reach boulevard Saint-Germain.” He starts to slide the paper across the bar, then stops, leaving my hand dangling expectantly in midair. “I’m glad you’re here, actually.”

“Oh?”

Ignatz steps out from behind the bar. “Oui. You had so many interesting things to say the other night.” He is larger than I remembered from last time I was here, reminding me of a grizzly bear.

Warmth creeps up my back. I never should have spoken about Papa’s work. I replay that night in the bar in my head, my tongue loosened by beer, too eager to say something meaningful and curry favor with the group. “It was nothing.”

“No, you had real views.”

I flush. “I never should have spoken at all.”

“Nonsense. Your wit added much to the discussion. But it also caused me to think, your contribution can be of most use to our cause.”

“I’m afraid I don’t quite understand.”

“As you may have gathered the other night, we’re interested in politics quite a bit. We’re more than just a ragtag group of artists and innkeepers. Some of us—not all but some—are actually doing something to further our beliefs in a just world.” What could they do, I want to ask. Write about freedom? Lobby for it? “You do believe that people should have the right to self-determination, don’t you?”

“Yes.” But I remember then my conversation with Papa about the limits of what could be done at the conference, the fact that not everyone’s claim to autonomy could be granted.

“We gather information, pass it on to Moscow or others who might be in a position to further those aims. You can help us if you’d like.”

I hesitate. What could I possibly do? He continues. “The information you shared about the Serbia vote was most helpful. If your father should say anything else …”

I cut him off. “He seldom speaks about his work.”

“Your father would not mind—ours and his cause are one and the same. I daresay he would want to help us himself, but for his position.”

Krysia had been so excited about Papa’s work. Maybe their interests really are aligned. “Perhaps …”

“So if you hear something of interest about what the Big Four might do …”

“I’ll tell Krysia,” I finish, regretting the words almost before they are out of my mouth.

“Oh, I wouldn’t burden her,” he interjects hurriedly. “She’s so caught up in her music. Best to let me know personally.”

Not answering, I snatch the paper with Krysia’s address and make my way out to the street, half-expecting him to try to stop me from leaving. The fractured cobblestones point in different directions, beckoning me to follow. Did Ignatz seriously think that I could—or would—help him?

Soon, I stop before the address Ignatz had given me. I step forward, studying the narrow four-story building. There is an iron gate overgrown with ivy, a small courtyard behind it leading to an arched wood door with carvings and a brass knocker at its center. The note indicates that Krysia lives on the top floor, but when I peer upward the shutters are drawn tight. Musicians, like artists, I suppose, work long into the night, and shut out the indecency of early morning. It is not yet ten o’clock, my arrival unannounced. I turn away, suddenly aware of the impulsiveness of my coming here. I should have asked Ignatz if Krysia had a telephone or perhaps had him forward a message. But I continue to stare upward, wishing I could somehow reach her.

“Hello,” a familiar voice says behind me. I turn to face Krysia in her blue cape. Contrary to what Ignatz had said, she does not look ill.

I notice then the rosary beads clutched in her right hand. “You were at church?”

She nods. “The old parish church at Saint-Séverin.”

“You’re devout,” I marvel. How does her faith mesh with her communist political views?

She ignores my remark. “Come in.” If she is put off by my unexpected visit, she gives no indication, but opens the door then steps aside to let me in. The lobby is dim and in disrepair but the banister carvings are ornate, belying a once-fine home. Paned windows swung inward to let in the fresh air, which carries a hint of smoke.

I follow her up the winding staircase, hanging back as she unlocks the door. She does not speak but walks to a tiny kitchen in the corner and puts on the kettle. The flat is just a single room, tall narrow windows overlooking a stone courtyard. The space is cozy, large pillows, everything in a maroon and gold reminiscent of something from India. There are books stacked in the corners, rich paintings on the wall. There is no table and I wonder where they eat. A candle, now extinguished, gives off a cinnamon smell.

I stand in the entranceway, clutching my gloves. To have shown up unannounced is bad enough, but I do not intend to overstay. A moment later, she carries two cups of coffee to the cushioned seat by the window. “Please, come sit.”

I take off my coat. “Your flat is lovely,” I remark, as I perch on the edge of the settee.

She waves her hand. “It’s a fine little place. We’ve been here since before the war, when the neighborhood was less in fashion.”

What might my own apartment be like? A vision pops into my mind of a garret like this, with lots of windows and light, a nook where I could drink my breakfast tea and gaze out the window. I’m not sure of the city in which my fantasy apartment exists—back in Berlin just steps from Papa, or somewhere farther away?

A cat slips quietly around the base of the chair before jumping up and folding itself into Krysia’s lap. I’m surprised—I’ve seen almost no pets since we’ve been back in Paris, none of the poodles and little terriers on leashes that littered the parks before the war. There are the strays, of course, animals too large and mangy to have been anyone’s pet for long, hurrying busily between the rubbish piles in the side streets. But there wasn’t enough food for the people during the war, much less animals, and it was a mercy I’m sure to put one’s beloved pet to sleep rather than let it starve. Some were probably eaten.

Through the floorboards comes a lively, unrecognizable tune from a gramophone. “I’m so sorry to intrude,” I apologize again.

“Not at all. Artists are a bit reclusive, but back home in Poland there are none of these formalities. Guests are always welcome at a moment’s notice.”

Relaxing somewhat, I take the cup she offers. “I hadn’t seen you. And then I heard that you were sick.”

She waves her hand dismissively. “Just a bad cold. These things get so exaggerated.” But there are circles beneath her eyes that suggest something more. She takes a sip of coffee, savoring it with relish. Coffee, like so many things, was scarce during the war, the ersatz mix of ground nuts and grains hardly a substitute.

My body goes slack with relief. “I was worried.” The fullness of my voice reveals my concern.

“It’s good to know that someone might notice if I dropped off the face of the earth.” She smiles faintly, her tone wry.

The cat hops across into my lap, purring low and warm. “She doesn’t like most people,” Krysia observes approvingly.

We drink our coffee in silence. Something about her absence and her tired expression do not make sense. I take a deep breath, then dive in. “Krysia, I wanted to ask you about the young women in the park.”

She blinks. “How do you know about that?”

“When you left Wilson’s reception, you went to the park….”

“You followed me then, too?” she asks, cutting me off.

“No. That is … I was curious where you were going and why.” I falter. “I guess I did follow you.”

“And I should ask the question—why exactly?” She has a point. We’ve spoken twice, spent a few hours together—hardly the kind of intimate friendship that warrants such probing questions.

“I was concerned.”

“You were curious,” she corrects. I was both, I concede inwardly. Of course I wanted to know what she was doing, understand her mystery. But I feel a certain kinship to Krysia, more so than I should for a woman I’ve only just met.

“Years ago I had a child,” she says, her voice a monotone. I stifle my shock. Whatever I had expected Krysia to say, it wasn’t that. “I was twenty-two when I got pregnant.” Just about the age I am now, though I cannot fathom the experience. “Old enough to make my own choices. The father—it wasn’t Marcin back then—was long since gone.” I struggle not to reach for her. “My parents wanted me to have it taken care of, to avoid the scandal that would have devastated them socially. I made the appointment and even went. I couldn’t go through with it, though. I had the baby.” Her voice cracks slightly. “But I was too afraid to try to raise her on my own. So I gave her up.”

Her. I remember the young women skating. One had been taller than the rest, with chestnut hair not unlike Krysia’s. She continues, “I go to the park each week to see her. Just once a week. Any more would only raise suspicion.”

“Have you ever spoken to her?”

She shakes her head. “I have no wish to intrude and complicate her life. I’ve tried to do the right thing—letting her go when I couldn’t support her, keeping an eye out for her safety. Yet it all gets twisted somehow. I mean, I had to give her up. But I can’t just abandon her, can I, and go on as though she doesn’t exist and this piece of me isn’t out there in the world?” She sounds lost, no longer confident and strong but a child herself somehow. Krysia is caught in a kind of purgatory, unable to leave the child but unable to be with her.

“She’s no longer a child. Perhaps if you spoke to her now, you could explain.”

“There are some doors that are not meant to be opened.” Her tone is firm.

I recall the girl, so similar to Krysia, except that she was slight, a thin slip of birch beside Krysia’s oak. “She looks well cared for.”

“The people who adopted her are good folks,” she agrees. “A bit more materialistic and less cultured than I would have wanted. But there’s time for that later, perhaps a year abroad, study at the Sorbonne.” She sounds as though she is planning a future that she will somehow be a part of, though that, of course, is impossible.

“Perhaps,” I soothe. I have no idea if she is right, but it is what she needs to hear. “Perhaps you’ll have children of your own. More children,” I add as she opens her mouth to protest that the girl is her own.

“Having Emilie nearly killed me.” Emilie. I do not know if that is the child’s actual name by her adopted parents, or just one Krysia uses in her mind. “She’s seventeen. But she hasn’t settled on a suitor that I can tell, I think because she is still studying.” There is a note of pride in Krysia’s voice, as if through her estranged child she could correct the mistakes of her own youth.

“I’ve never told anyone.” Underlying her voice is a plea that I not judge her choices. “I don’t know why I’m telling you.” Because I caught you, I want to say. But she could have lied to me, made up a story about the girls in the park. No, there is something about me that she trusts almost instinctively. I’ve always had that way about me, that makes people want to talk and share.

“What about your parents?”

“There was a time they would not speak to me. Now we’re civil since we’ve put all that behind us.” She places heavy irony on the last two words, as though acknowledging that it is anything but in the past.

“This week she didn’t appear at the park. Listening to the others, I learned that she’d been taken ill.” I understand then Krysia’s absence, the circles beneath her eyes that came not from her own sickness but worry about her child. “It was the worst thing in the world. I wanted to go to her in the hospital but, of course, I couldn’t. So I’ve been in church, praying almost nonstop for her recovery.” No, madly liberal, communist Krysia was not religious. It was the helplessness and despair of a sick child she could not be with that had literally brought Krysia to her knees. “She’s turned the corner now and is recovering.”

Yet Krysia still prayed. “When I didn’t see you for a time, I thought maybe I had said or done something to offend you,” I say, changing the subject. Then I stop, realizing how insecure I sound.

“Not at all. I’m glad to know you. I have Marcin, of course, but I’ve forgotten how pleasant the company of another woman can be.”

I nod. “Me, too.” I am not comfortable in the company of women. I dislike their gossipy talk and the way they eye one another as if in constant competition. But Krysia is different somehow. For a minute I consider sharing Ignatz’s request that I help provide information. But Ignatz bade me not tell her about our conversation, almost as if he considers her too vulnerable and weak to be trusted. I do not want to bother her now, while she is so worried about Emilie.

She picks up some knitting needles and yarn beside her. Her hands are so often in motion, playing the piano, knitting—like two birds she needs to keep occupied so they don’t fly away.

“So have you made any decisions?” she asks abruptly.

“Excuse me?”

“When we last spoke, you were trying to figure out what you were going to do.” She watches me expectantly, as though I was supposed to have remolded my life plan in a few short weeks. Why must I do at all? As a girl, no one expected me to do or be—I just was, a happy state of affairs that I should have liked to carry on indefinitely. In truth, our conversation and Krysia’s challenge had prickled at me nonstop since our last meeting. But I have no new answers. There have always been expectations: I will be wife to Stefan, a mother someday if his condition still permits it. Those things just meant being an appendage to the lives of others, I see now. Could that possibly be enough?

“You have a real gift with words,” she adds when I do not answer. “Have you ever considered being a writer?”

I laugh, toss my head. “A writer? What would I say? You have to have more than just words—you need life experience and I have so little of that.”

“Where will you go after the conference?” she asks, trying an easier question.

“Back to Berlin with Papa, I suppose.”

She scrutinizes her knitting, then pulls out a stitch. “Why? Why not see a bit of the world now, while you can?”

“But my fiancé …”

“Ah yes, you mentioned him the other night, fleetingly. Once you go back to him, there will be a wedding, then children. There will always be something to stop you. You only have right now. Go while you can.”

“I’ll go back to Stefan after the conference,” I say stubbornly.

“You sound enthralled.”

“I didn’t mean it that way.” But it isn’t my tone that she has taken issue with—it is the fact that I am going back at all.

“Is that what you want?”

I start to say yes, then stop. It is a lie.

“Then why go?”

“Because he is my fiancé. And he was badly wounded.”

I expect her to ask how he was hurt, the seriousness of his injuries. “Do you love him?” I’m not sure what love is, really. When I was fifteen, Stefan and our tiny neighborhood, the park where we would walk together, and our quiet cinema dates, were the only world I had ever known. Stefan would have changed during the war.

“I care for him.”

“That isn’t the same.”

“I know.” I turn to gaze out the window at the courtyard below. “I feel so differently now.”

“Or maybe you feel the same, but you’ve changed and so those feelings are no longer enough.”

I consider this. Part of me has always sensed that there were differences. I recall a conversation Stefan and I had once about my mother. I’d found an old playbill from a show she’d done in Morocco and shown it to him. “How exciting,” I remarked, “to have traveled the world.”

But Stefan had looked at me blankly. With everything he wanted right here in Berlin—his family and me—he had no desire to leave. “It must have been terribly difficult,” he replied, “not to mention dangerous.”

I could see it in his eyes, too, the day he left for the army. “You’ll get to go so many places,” I’d offered as we stood on the platform and said goodbye, trying to force optimism into my voice. “Belgium, Holland, maybe even France.” But Stefan had never wanted to leave in the first place, whereas I could not wait to go. No, the differences were there even before the war, but it had taken the years apart to make me perceive them clearly. Now they are magnified, not just by time, but the ways in which I had changed, as well.

“Maybe,” I reply to Krysia. “We were so young and four years apart feels like a lifetime. Sometimes he seems more like an idea than a person. I hate feeling this way. And he needs me.”

“A sense of obligation is no way to start a life,” she presses.

“Loyalty is important.” My voice sounds tinny and weak.

“So is happiness. Would you want someone to marry you for such a reason?”

“No, of course not.” But I am not lying wounded in a hospital bed, with no prospect of a future. I am suddenly annoyed. I barely know Krysia. Why is she asking me such things? “I should go.” I stand and put on my coat. “Thank you for the coffee.”

I half wish she will try to stop me, but she nods, rising. “Thank you for calling. I hope to see you again soon.”

Outside it is warmer now, the late-morning sun taking away some of the chill. The sidewalks are now lively with pedestrians, merchants and deliverymen unloading crates from lorries. As I make my way toward the metro, Krysia’s questions about Stefan prickle at me. I hear her voice, exhorting me to see the world now, while I still can. A thousand objections roar through my brain: I can’t leave Papa. I can’t travel alone.

Nothing has changed—my problems loom as large as ever. But despite my earlier annoyance, it felt good to share my fears about Stefan and a life together with Krysia, to verbalize to somebody the thoughts and feelings I’d barely dared to acknowledge to myself for so long. And Krysia confiding her story of Emilie helped, as well. Learning that someone as strong and self-assured as Krysia also wrestles with the past and the right thing to do makes me feel somehow less alone. She seems to enjoy my company, though perhaps I am simply a proxy for the daughter she so desperately wants to know but cannot. Squaring my shoulders, I start down the street with a lighter gait than I’ve had since before the war.

Forty minutes later, I reach our suite at the hotel. I open the door and stop. The curtains are drawn and only faint daylight filters in. A rustling noise at the desk startles me and I jump. Papa is here, hunched over the desk in the darkness, when he should have been at the ministry. “Papa?” Alarmed, I rush forward. He does not move. I put my hand on his shoulder, fearful that it is his heart and the worst has happened. “Papa, are you well?”

He straightens but his expression is dazed as though he does not see or recognize me. Before him on the desk sits a newspaper. “There’s been an attempt on Clemenceau’s life.” I pick up the paper. My breath catches as I take in the photograph of the would-be assassin. The dark-eyed boy from the La Closerie des Lilas stares back at me.

“The attacker possessed information from the conference that was not public, information that prompted him to act.” Papa drops his head to his hands once more. “And I’m afraid they’re going to blame it on me.”