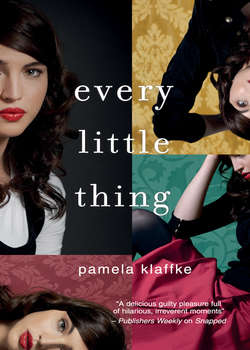

Читать книгу Every Little Thing - Pamela Klaffke - Страница 7

LAW & TAXES

ОглавлениеNow I know why people hate lawyers—and the government—and mustachioed past-middle-age men who keep trying to hug them when they don’t want to be touched.

I’m standing with Ron on the sidewalk outside of the estate lawyer’s office, smoking, and trying to reflect the sun with the Medusa-head gold buttons of the ridiculous Versace suit my mother bought me years ago, during one of her attempts to fancy me up. If I could just get the perfect angle I’m sure I could blind one of these lunchtime busybodies who keep elbowing past and glaring at me for what could be any number of reasons: my smoking, my hair, my suit, my boots, all of the above. Or it could be the fact that I’m standing in the middle of the sidewalk and everyone has to walk around me.

I have no intention of moving. Instead, I move my legs as wide apart as the suit skirt will permit, and take up even more room. It’s not very ladylike and my mother certainly would not approve. But I don’t care about anything—other than getting Ron to stop touching me and shutting him up. He keeps telling me it’s going to be okay, that everything will work out, that he’s there if I need him, that if I’m short on cash, he’s glad to help out. I’d rather turn tricks, but that may not be very lucrative considering the state of my body, with its jiggle and bruises and lumps. At best, I’d be a street whore, queen of the five-dollar blow job. I couldn’t pass for a high-end escort and I would rather die than strip.

I could get a webcam and talk dirty, looking sexy and stoned, for businessmen and suburban dads who haven’t yet made the leap to the hardcore stuff, the ones who pretend if it’s not actually sex then they’re not actually cheating. I could get them off then listen to them talk—or type—about their guilt, their shitty marriages, how it was never supposed to be this way, about how they’re old and can’t believe they’re bald. I’d charge by the minute and rates would escalate the more they whine.

None of this is very realistic. I will not be a whore. I will get in the taxi and go to the hotel. I will pack up my things and check out. Room service, dry cleaning, concierge, everything—it’s gone—just like my emergency credit card, the one my mother gave me, the one I used to pay for my flight down here, the one I was using to pay for my suite at the Fairmont Hotel. The estate law yer said it will be canceled this after noon. I explained I was broke and therefore was experiencing a genuine emergency. He smiled and leaned forward, resting his arms on his big desk. “I know this is a difficult time,” he said. “But there is a set way of doing things.” And by things he meant that there are taxes and expenses to be paid before the estate can be settled. It could take months, or at best, weeks, and until then my mother’s accounts are frozen. I have nothing and am stuck in San Francisco with nowhere to stay.

“You’re more than welcome to stay with me,” Ron says as we stand on the sidewalk. The taxi is taking forever to arrive and I wish I had a snack in my bag. Unfortunately, San Francisco is not the kind of city where you can easily flag down a cab on the street. You have to call and order and wait. “I know it could be—” Ron pauses and looks down. “I know it could be uncomfortable for you, being at your mother’s apartment.”

I’m not really homeless, out on my ass giving cheap blow jobs to junkies and fuckups in the Tenderloin. And I don’t have to stay with Ron or ask Seth or Janet to stay with them. In my bag I have the keys to my mother’s apartment in North Beach. She bought it in the mid-seventies, shortly before I was born, when she fancied herself bohemian. We lived there between her marriages and she always wrote there regardless of what man she was involved with. She called it her refuge and couldn’t have been more delighted when the neighborhood gentrified, going from alt-ethnic enclave to Yuppie haven, as her seventies’ pseudo-bohemian persona morphed into a eighties’ money-hungry conservative in royal blue and shoulder pads, with a bag of blow in her jewel-encrusted clutch. She is—was—such a cliché.

“I mean, I know that you and your mother didn’t always see eye to eye and that this must be very hard on you, Mason, not having seen her or talked to her in some time … it’s understandable that you might not be comfortable staying at the apartment.” Ron is blathering. He needs to shut up. And why does he keep saying you’ll be uncomfortable, you’ll be uncomfortable? I wouldn’t be uncomfortable—it’s where I grew up, sort of, sometimes. I have a bedroom there. At least I think I still do. My mother would say that: “There’s always a bed waiting for you. You can always come home.”

“Britt—your mother—she called it her refuge, you know,” Ron says. He’s getting weepy, red-faced on the verge of blubber.

“I know she did.” I say this through clenched teeth, angry, not sad. Ron’s mustache is disgusting. It makes me think of the column my mother once wrote about mustache versus non-mustache oral sex. I get a flash of my mother laid out on Ron’s tacky bed, wearing magenta lipstick, Ron’s mustache tickling her monkey, as she wrote in her column. I feel sick. I try to conjure other images in my head, of puppies, fast food, Seth and cowboys—anything. But I can’t erase it. Tickling my monkey. Oh God. “I did know my own mother,” I snap at Ron. Where is that fucking taxi?

“Mason, I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to imply that you didn’t. Of course you knew your mother. You don’t have to be close or keep in touch to know someone. I’m just saying—”

“You’ve said enough.” I’m not falling for his passive-aggressive bullshit. You don’t have to be close; you don’t have to keep in touch. He’s probably pissed that he only gets a fraction of what I do of my mother’s estate if there’s anything left after the lawyer’s fees and taxes.

I turn my body as far from Ron as I possibly can once we get in the taxi that has finally arrived. I open the window and let the dense spring air blow onto my face. We drive past familiar spaces that are now something new. We drive up Kearny through downtown and I notice that the Hello Kitty store is gone. I’m sad about this but couldn’t say why. Seth and I used to load up on Hello Kitty notepads and pencils we’d buy at shops in Japantown when we were teenagers, and use them in school. People were always so surprised: the pair of us who dressed head-to-toe in black, using cutesy pink paper and pens with kitties and hearts.

Then Hello Kitty got huge, went superglobal. There was the video cartoon series and this pissed us off. The original, authentic Hello Kitty had no mouth—not until the videos. It was better when she couldn’t speak. When the big Sanrio store on Kearney opened it was immediately packed with tourists and little girls. Seth and I burned our Hello Kitty things in the fireplace in the home of my mother’s fourth husband.

Anything plastic—the key rings, the soft, miniature binders—smoked and smelled. The alarm triggered and the fire trucks came. We were ushered onto the street as we tried to explain. Neighbors gawked and my mother’s fourth husband, Gregory, had a fit. He was rich, old money—very private, he liked to say. That was crap, of course. If he was really so private, he shouldn’t have married a newspaper columnist with a well-known habit for writing about every embarrassing detail of her life and the lives of those around her. As if everyone didn’t know he was “Griffin,” her rich, society husband. As if he didn’t secretly love it. They all did until they started to hate the things they thought they loved about my mother in the first place.

The Hello Kitty false alarm was some sort of final straw between Gregory and my mother. Their arguments escalated and became more frequent, and soon we were back in North Beach spending my mother’s substantial alimony checks on an extravagant red-and-black lacquer early-nineties makeover for the apartment. I demanded baroque wallpaper in red and gold with flocked, flying black bats. It was specially ordered from Italy and cost three hundred dollars a roll.

The Hello Kitty store is gone, no longer poised for Seth and me to walk by and roll our eyes, aghast at the branding of toasters and vibrators and cars with her image. We can’t just happen by on our way to Nordstrom—if we were, for some strange reason, going to Nordstrom—and remember the Hello Kitty false alarm and how we used to scour the shops in Japantown. The store’s not there to act as a prompt for us to complain about how Hello Kitty is such a sellout and how things aren’t at all like they used to be.

“Will I see you again before you leave?” Ron asks as a bellhop opens the taxi door to let me out in front of the hotel. I don’t offer to pay or chip in. I’m broke. He can pay and get all passive-aggressive about it later. I’ll mail him a check for my part of the fare when I get my inheritance. I’ll owe him nothing and we’ll never have to speak again. “We could have lunch?”

Lunch? What is he on about? And I wish he’d stop using that horrible, patronizing tone. He doesn’t have to talk to me like I’m retarded or some horrible daughter who wasn’t close to her mother and didn’t keep in touch.

“Mason?”

I sigh and look over my shoulder. “Fine. Yes. We can have lunch,” I say just to get him to shut up. There will be no lunch. I barely know the man.