Читать книгу Billy Connolly - Pamela Stephenson, Pamela Stephenson - Страница 6

Introduction

ОглавлениеMuch has been written already about the chimerical joker known to the world as ‘Billy Connolly’. That creature, however, is a fictional one, a Bill-o’-the-wisp that dances from tabloid to tome with relentless inaccuracy. Nothing unusual about that: everyone who comes to public attention is reflected in fragments, half-truths and downright lies since every observer projects his own fantasy upon the famous person in an illusory folie à deux. In any case, when it comes to chronicling a person’s life there is no such thing as absolute reality, even if the writer happens to be his wife and a ‘shrink’ to boot. I, for one, subscribe to the notion implied by the Heisenberg Principle, that nothing in the universe can ever be accurately observed because the act of observation always changes it. For every one life, there are a million observed realities, including several of the subject’s. ‘A stranger caught in a portrait of myself,’ as Nabokov described the phenomenon, is commonly reflected back to a bemused interviewee.

‘Who HE?’ Billy will shout, slapping down the latest visual or written appraisal he considers is a dark imitation of his former self. In my paradigm, every person holds the reality of his own experience either in his mind’s eye or just below the surface of consciousness, or even deeper in the unconscious mind; but in the latter level we are all strangers, even to ourselves, and the mysterious workings of our unfathomed parts are revealed only in our dreams. Even within families, shared times are experienced differently, coloured by the age, family role or state of mind of each member. Small wonder, then, that some of Billy’s relatives and friends have disparate impressions of the following events. For Billy, reading each chapter after completion has elicited the shock of self-confrontation, accompanied by frequent laughter, occasional fury and a few precious tears as he painfully re-experienced many traumatic events. Most rewardingly for the author, the process of drawing together the following occurrences and providing insights might well have been a catalyst for his further healing, although Billy will have none of that: ‘Pish!’ he cries. ‘As my old granny Flora used to say, “The more you know, the less the better.”’ Another gem of Flora’s was: ‘Never clothe your language in ragged attire.’ Billy obviously missed the word ‘never’ because, purely in an attempt to please his dear old gran, he continues to say the ‘f ’ word in every single sentence and double on Sundays. I actually wondered about Tourette’s syndrome when I first met him. People try to stop Billy’s profanity, but that only encourages him. I myself have found great utility in those special collars for large pet dogs, with the remote control device that administers savage electric shocks to the neck of any beast that gets too close to the mark. Undetectable beneath his polka-dot shirt collar, it came in very handy recently when Billy gave a graduation address at our children’s school. You know where this is leading … try to guess the number of ‘f ’ words in this book before you read it. Be creative: it’s just like guessing the number of marbles in a jar so run a sweep, raise money for charity or decide who buys the next round. The answer can be found later.

I’m just playing with you. When this book was first published, people were frantically turning pages to satisfy their mathematical sensibilities. This was a trap. If observed, one risked being accused of committing the appalling readers’ crime of turning to the last page for an unearned glimpse of the ending. But by now, almost everyone who picks up this book knows how Billy’s childhood story ends – with the triumph of a successful life as a beloved comedian. However, the paragraphs above were written ten years ago, when HarperCollins was just about to publish Billy for the first time. It was a nerve-wracking time. In the run-up to publication, both author and subject were mightily scared because this book is not what people might have been expecting – a frothy romp through the life and times of Billy Connolly, funny man and hilarious raconteur. Oh, one could write a facile account of him (the time that silly big man ran naked round Piccadilly Circus, got drunk with Elton, and danced with Parky) but, in my opinion, that would be dishonest. No, there’s much, much more to his story and, both as a psychologist and as Billy’s wife, I believed the truth was begging to be told.

Billy’s real story is a dark and painful tale of a boy who was deprived of a sense of safety in the world. This early trauma had a massive influence on the man he became – a survivor of abuse whose psyche still bears the scars, and whose resultant, deep self-loathing prompted self-destructive tendencies. My many years working as a psychotherapist have taught me that it is usually healing to bring one’s dark secrets into the light and find that one is still accepted and loved. And ever since I caught my husband crying by the TV when psychologist John Bradshaw was helping a man come to terms with his childhood abuse, I wanted that for Billy.

But he was afraid that, when readers discovered his ‘shameful’ secrets, they would turn their backs on him out of scorn, pity, or embarrassment. And I was concerned that, having convinced him to tell the world his extraordinary story – and being the architect of that decision – I bore considerable responsibility for the outcome. What if it went wrong? What if I had misjudged how people would react? What if Billy became retraumatized by it all? Public revelations cannot be retracted. And revisiting terrible events under the wrong circumstances can cause further harm.

Fortunately, many of the millions of people who read Billy reached out to my husband in wonderfully positive ways. We were both unprepared – not only for the unprecedented success of the book, but for the massive and widespread outpouring of support and acceptance. Readers let Billy know how much they empathized with him, adored him and, in many cases, shared similar stories of violation, torture and humiliation. Far from being rejected, Billy became a poster child for those who seek to overcome the challenging legacy of a painful childhood, who hope eventually to find that the revenge of survival and future happiness – let alone success – is sweet.

Billy and I received hundreds of letters from people who poured out their own, touching stories of childhood torment. Some even said this was the first time they had dared tell their own story, and that it was Billy who had finally given them the courage. It made Billy very happy to learn that others gleaned hope and healing from his story. And for me, it was particularly gratifying to learn that the book seemed to help depressed, abused, or hopeless people.

There’s nothing like facing the demons from one’s past – wrenching them from the realm of the unconscious and talking about them with an empathic person – to lead one to a sense of peace and a healthy perspective. Nowadays, Billy speaks compassionately about his father, and says he has forgiven him. But that’s no easy task for any survivor of abuse; psychologists know that forgiveness and healing do not necessarily go hand in hand, and I am well aware Billy still harbours reserves of fury that may never, ever be assuaged. He continues to be a somewhat tortured soul, occasionally as insecure and frightened as he was as an abandoned four-year-old. And he still struggles with his attention disorder (which is only a problem offstage, since losing his way while telling a story has become an aspect of his stand-up concerts that audiences thoroughly enjoy). He also struggles with short-term memory, organization, gaining a gestalt perspective on anything, and anxiety; pitching himself on stage has not become any easier than it was when he first started.

But no one calls Billy ‘stupid’ like they did when he was a schoolboy – least of all me. Billy is one of the brightest and best-read people I’ve ever met. However, like many others of his generation, he is challenged by the cyber world. He still thinks of the Internet as ‘The Great Anorak in the Sky’. ‘It’s getting worse and worse,’ he complains. ‘It’s made people fucking boring. It’s separating them. Now they’re all sitting in rooms typing to people they don’t know.’ In fact, Billy’s current enemies are inhuman ones: Internet access, passwords (the remembering of them), and ‘How do I get the Celtic scores on this raspberry … blueberry … or whatever the fuck it’s called?’

Yes, Billy is still an expert in the fine art of swearing. He is also the proud owner of a Glaswegian accent, which has mellowed only slightly over the years. In fact, when I first met the man I could barely understand a word he said, and sometimes I think that was a blessing. Now, I love the Scottish accent, but at home it can lead to the ‘Chinese Whispers’ kind of misunderstanding. Once, when Billy and I were watching the TV news with our adult children and some extended family, I commented that I adored the CNN reporter Anderson Cooper. ‘Grey-haired cunt!’ retorted my husband, in what seemed like jealous pique. Everybody looked at him in alarm. ‘Billy!’ I cried. ‘What’s that poor man ever done to you?’ Billy stared at me, mystified. It turned out he’d actually said ‘Great hair-cut!’

Over the years, Billy has gradually suffered a little hearing loss, which means he is even more likely to talk about someone in loud, disparaging terms, imagining they can’t hear. A few Christmases ago he fell asleep in the middle of a family outing to the seasonal Rockettes show at Radio City Music Hall in New York – high-kicking glamour girls in furry bikinis, a ridiculously jovial Santa, and way too much fake snow. The kids and I took it in turns to try to keep him awake, or at least minimize his thunderous snoring, until we realized that this was a lost cause. Halfway through the show he suddenly woke up and, to our deep embarrassment, shouted above the orchestra: ‘For fuck’s sake, Pamela, how much more of this shite is left?’

After Billy I wrote a follow-up book about him – an account of his sixtieth year – called Bravemouth. Once that had been published I decided it would be remarkably unhealthy – not to mention annoying – to write a single word about him, ever again. Frankly, I was exhausted from focusing so unswervingly on my husband; that was well above the call of duty for any wife. ‘I’m sick of you,’ I announced at last. ‘In future, write your own stuff!’ I went on to have adventures in the South Seas and Indonesia, and also scribbled away on the subjects of psychology and sex. It was such a relief.

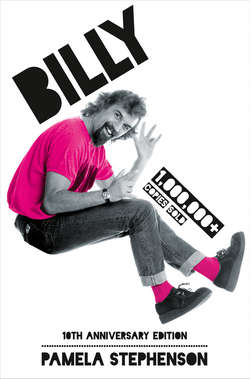

But who exactly is our protagonist nowadays? Well, he’s much the same. We now live in New York, where Billy can be spotted tramping the downtown alleys in search of an elusive banjo music shop, a cigar den, or a purveyor of outrageous socks. His sock choices have changed a little over the years; he has gravitated from the luminous to the gaudy stripe. Now he prefers a horizontal red, turquoise, orange, brown, and white repeating stripe to those he was wearing on the original Billy cover: luminous pink, with pictures of Elvis on the ankle. ‘I still love those,’ says Billy, ‘but I find them awful hard to find.’

Billy claims to be part of an unofficial ‘inner circle’ of people who wear wild socks. ‘We like each other,’ he says. ‘We always give each other a nod in the cigar shop.’ Billy says he’s never met a cigar smoker or a fl y-fisher that he didn’t like. He seeks to land ‘a wee troutie’ in every brook he can find, from Canada to New Zealand, while New York cigar dens have replaced Glaswegian pubs as the haunts where Billy can enjoy largely male company. ‘My New York pals,’ he says, ‘are a great cross-section: Wall Street guys, New York cops, and Arthur who makes art from bashed-up cans that have been run over by cars.’ Nevertheless, Billy keeps close contact with his Glasgow chums. He frequently returns to his home town – where he was recently honoured by being presented with the Freedom of the City of Glasgow. ‘It’s fucking great,’ said Billy. ‘According to old by-laws I can now graze my cows on Glasgow Green, fish in the Clyde, and be present at all court hearings! And if they send me to jail I get my own cell; no bugger’s going to interfere with my jacksie.’

Billy definitely does not restrict his friends to other living national treasures, although he is beloved by many of that ilk. ‘He is inspirational and I absolutely adore him,’ said Dame Judi Dench. ‘One-off, unique, irreplaceable,’ echoed Sir Michael Parkinson. ‘The most frankly beautiful Scottish person with a shite beard I ever met,’ said Sir Bob Geldof. Billy is considered a ‘comedian’s comedian’, and he’s extraordinarily generous in his appreciation of others in his field. ‘He’s my inspiration,’ said Eddie Izzard. ‘He was doing alternative comedy fifteen years before anybody else.’ ‘He is the funniest man in the world,’ said Robbie Coltrane. But it was Billy’s close pal Robin Williams who summed it all up when he said: ‘I don’t have a clue who Billy is.’

Age has not slowed Billy down, and I suppose it’s remarkable that he continues to have a flourishing career, both in movies, television, and in his live performances. The run-up months to London’s Olympics alone have seen him undertake a major, sold-out UK tour of forty-two dates. And Billy still seems to hop from one movie to another. One of the highlights of his movie career in recent times was Quartet with Maggie Smith, Michael Gambon, Pauline Collins, and Tom Courtney, about four ageing opera singers who live together in a residential home. It was directed by his pal Dustin Hoffman, who once described Billy as ‘a big fart that carries no offensive odour’.

A fantastically entertaining TV series about Billy’s trike ride from Chicago to Los Angeles, along the USA’s famous Route Sixty-Six, was broadcast on ITV in 2011 – although Billy was lucky to finish it. The day he neared Flagstaff, Arizona, I was doing something that hardly befits a psychologist – having my photograph taken for a newspaper. ‘What’s your husband up to?’ asked the photographer. ‘Oh, he’s riding his trike along Route Sixty-Six for a TV show,’ I replied. ‘Really?’ said the man. ‘I’m a Harley biker myself.’ ‘Oh, thank heavens I’ve persuaded him away from those things,’ I said. ‘Trikes seem to be a lot more stable.’ The photographer’s next words were portentous. ‘Not necessarily,’ he said. ‘They can tip if you turn them in too small an arc …’ I sighed and made a mental note to address that the next time I saw my husband. It could not have been more than five minutes later that Billy’s manager Steve called. ‘Billy didn’t want to worry you,’ he started. ‘He’s OK, but he came off his trike.’

I felt the sensations of shock flood into my body. ‘What happened?’ I asked Billy, when I finally managed to speak to him. ‘Oh, I tried to copy a manoeuvre of the camera van (which has four-wheel drive). See, Route Sixty-Six is shaped like a snake, and running through the snake is the interstate highway, so there’s a series of dead ends that means you often have to go back. Anyway, we came to a dead end where they’d bulldozed the dirt onto a hillock. The van managed to drive on top of this mound and turn round, but when I tried it I was going too fast and my trike fell on top of me.’ ‘What injuries do you have?’ I asked. ‘Och, I just broke a rib and skinned my knee cap very badly. It’s a very pretty shade of purpley red. My finger is all swollen and I had to get my wedding ring off. But I’m in very little pain. They had to hold me down – I didn’t think I was hurt so I wanted to get up.’ Before long, Billy was in a helicopter on his way to Flagstaff Hospital. A medic was kneeling by his stretcher. ‘What kind of pain are you in?’ he asked. ‘I’m OK,’ replied Billy. ‘If ten’s the worst pain you’ve ever felt, where are you now?’ asked the medic. ‘About one and a half,’ replied Billy, nonchalantly. ‘Are you sure?’ asked the medic, incredulously. ‘You’ve just broken a rib!’ But Billy stuck to his story. ‘Look, you can tell me,’ the medic said insistently, waving a morphine drip. ‘I’ve got the whole candy store here …’

But Billy eschewed the pharmaceuticals and entertained the medical flight team instead. It could have been a lot worse. By the time I spoke to him in Flagstaff he’d been X-rayed, stitched up, and released. His cheery voice and attitude betrayed his idiosyncratic and macabre view of the world, as well as his attention to curious detail. ‘The emergency doctors had to cut off my nice leather jacket,’ he said, ‘but they’d done that to bikers so many times before, they knew exactly how to cut the seams so it could be sewn back together again!’ Hardly what I wanted to hear. And hardly reassurance that he had learned any kind of lesson from his accident. ‘Billy, you seem to care more about your leathers than your own skin,’ I said. ‘From now on, do you think you could manage to stay off any kind of road vehicle that lacks a roof?’ ‘Pish bah pooh,’ was his predictable response.

As you’ll discover in Chapter Two, Billy has been a risktaker from early childhood, and I’ve often wondered how he managed to make it to his teens. I now understand that his apparently reckless early stunts were instigated as much by despair as by dare-devilry (depressed, abused, misunderstood children often engage in activities that psychologists recognize as signs of passive suicidality). Hopefully, this most recent mishap may have curtailed Billy’s vroom-vroom craziness to some extent. Trying to be the voice of reason is exhausting for me, and anyway, he is understandably unwilling to accept warnings from a woman who delights in facing storms on the high seas, travelling in hostile environments, and scuba diving among sharks of every variety.

As I write this, Billy is preparing to leave for New Zealand to start work on the latest Peter Jackson blockbuster movie, The Hobbit, in which he will play the King of the Dwarves. Aghhh! It’s so trying for me that he should have such a part. Not because he’ll be away from our New York home for three months – no, we’re used to long separations. It’s trying because Billy regards the legitimate use of the word ‘dwarves’ as a triumph over my long-standing protestations that it’s ‘not politically correct’. In my presence, he loves to tell a tale about a little person – whom he calls a ‘dwarf ’, just to see me squirm. The following is the tale, with ‘little person’ substituted for ‘dwarf ’:

Apparently, a pal of Billy’s sister Florence was on a Glasgow bus when a woman who happened to be a little person got on. A schoolgirl stood up to offer her a seat, but the woman declined. ‘You’re just giving me your seat because I’m a little person,’ she said. ‘I can stand perfectly well.’ A bit later, another woman, who was about to get off, waved the little person towards her seat. Another sour ‘I don’t want it’ was the response, which geared the giver onto her high horse. ‘I’m not offering you this seat because you’re a little person,’ she shouted. ‘I’m offering it because you’re a woman. And by the way, I think you were very unfair to that young schoolgirl, who was just trying to be nice!’ At this point in the story, Billy always starts to giggle in anticipation of the punch line. ‘And what’s more,’ continued the woman with mounting fury, ‘when you get home, I hope Snow White kicks your arse!’

See, the story works just as well without the use of the word ‘dwarf ’, don’t you think? What? Well, whose side are you on anyway? It’s impossible to argue with Billy about such things, but I feel duty-bound to try. ‘I’m calling Peter Jackson,’ I announced. ‘I’m going to suggest he rename your role as “the King of the Little People”.’ Billy ignored this. ‘Did I ever tell you that my granny rescued a child whom she thought was too young to be crossing the road and discovered it was a wee man? Went and grabbed him – scooped him up from the middle of the traffic and gave him a good scolding: “I’ll tan your arse!” she said, before she realized it was a dwarf.’ ‘Billy!’ I cried. ‘LITTLE PERSON! That’s what they wish to be called and we should respect that!’ ‘Now stop it, Pamela,’ he insisted. ‘I’m talking about a dwarf, not a little person. You put a little person and a dwarf together in the same room – they both know which one’s the dwarf!’

I sincerely apologize to any little people who might be reading this. Neither Billy nor I mean to be offensive by the above discussion; it’s never easy trying to navigate the fine, snaky line between comedy and propriety. And, if it’s any consolation, Billy tends to be far more vicious about people his own height – and often for no good reason. I once heard him being ridiculously savage about a perfectly innocuous fellow traveller: ‘What’s he going to do for a face when King Kong wants his arse back?’ he ranted. The man’s crime? Having the temerity to be talking on his cell phone.

To be honest, I have long since given up trying to tame my husband. And anyway, I secretly enjoy his oppositional style, and would probably be lost without the challenge. Yes, he’s wonderfully grumpy (if you like that kind of thing). In fact, he’s ornery about almost everything, including seeing the doctor, informing me of his schedule, or eating anything green with his fish pie. Having said that, he is an excellent cook, with specialities that include great curries, apple pie, and a killer macaroni cheese. He has not touched alcohol for around twenty-eight years, but loves to take a deep whiff of my dinnertime red wine. Billy remains a slim, fish-eating vegetarian with a full head of hair and, just like his grandfather, will probably live to be nearly a hundred. It’s a little scary, though, to imagine an age-indexed increase on the curmudgeonly scale; by his tenth decade his vocabulary of communication may well consist only of frowns, farts, and just one word (yes, that one).

Ten years after this book was first published, the artist is in residence. The man swishing confidently around the bijou Birmingham art gallery – the new home of his latest creative efforts in the form of extraordinary pen drawings – is now formally known as Billy Connolly CBE, visual artist. It’s not exactly a career change, more a career addendum for the Artist Formerly Known only as Billy Connolly, King of Comedy. He’s now both – as well as Master of Mirth, Chancellor of Chortling, Baron of Banjoing and Specialist in the School of Hard Knocks. I confess I also think of him as Commander Curmudgeonly from time to time, as well as Archdeacon of Amnesia. Typically, he has forgotten to tell me about his important first art opening, where a selection of these drawings was to be shown in a small exhibition entitled Born in the Rain. When I finally do learn about this event – on the same day – I’m several hours away in London. I race to Euston for a fast train, and arrive at the gallery just fifteen minutes before the end of the show. I spy Billy just inside the door, a svelte, chic baron in a collarless tweed jacket and a silk scarf covered with butterflies. His hair is cropped shorter than usual for his latest movie. But he’s thrilled by this brand-new role. ‘I’ll be wearing an opera cape and cigarette holder next!’ he says.

I watch Billy, surrounded by people who can’t believe their luck to be standing next to the man. Fortunately, many of them are also art lovers, eager to take home a slice of Billyness to hang in their living rooms. There’s a queue for his stunning drawings and prints, for which he has devised titles such as Extinct Scottish Amphibian, Pantomime Giraffe, Celtic Bling, Chookie Birdie, and A Load of Old Bollocks. He has been working on these for several years now, hunched over his drawing pad for many hours at a time. I especially love the darker, almost sinister ones, such as The Staff, which is a row of similar, expressionless people in gas masks, all facing the same way. Told you it was dark. But as Robert Stoller said, ‘Kitsch is the corpse that’s left when art has lost its anger.’ Throughout the afternoon, Billy tells me, a pointed question has been posed time and time again: ‘What does your psychologist wife think of your drawings?’ ‘Oh,’ replied Billy, ‘she just peers at them then walks away with a superior, shrinky look on her face.’ Rubbish. I take photos of this triumph and text them to our kids. ‘Your father is officially an artist!’ I crow, as if I had anything to do with it. Well, I probably did – especially those pieces that were born of fury or frustration.

Is it ever easy to be with the same person for more than thirty years? Sometimes I think I was not the right wife for Billy. I’m too self-determining, career-oriented, eager for adventure, and busy. Billy might even add ‘bossy’. ‘If you hadn’t been married to me,’ I asked him recently, ‘whom would you have wanted to be your wife instead?’ ‘Sandra Bullock,’ he replied, without a moment’s hesitation. ‘I think she’s lovely. There’s a wee promise in her face. Or maybe Sinéad Cusack, ’cause she’s fanciable, too. And that blonde woman on CSI Miami who looks like you Pamela. Well, she’s OK …’ Billy must have caught my horrified micro-expression, ‘… but she’s not as nice as you …’ Good to know.

Billy was wonderfully supportive when, against his advice, I took part in the BBC television show Strictly Come Dancing. He giggled uncontrollably at my first waltz, but was later caught looking misty-eyed when my dance partner James Jordan performed a routine that helped catapult us to the finals. I wondered if – even slightly hoped – Billy would be jealous of James, but my husband was far too self-assured for that. But he warned me: ‘I wouldn’t trust a man who wore such tight trousers.’ Billy now complains he’s a ‘tango widow’ because I take off after dinner to dance until midnight. ‘Why don’t you come along?’ I frequently ask. Billy has had one tango lesson, and there are black-and-white shoes in his wardrobe, so he is partly equipped for a milonga. ‘Think I’ll give it a miss,’ he says. ‘Watching snake-hipped foreigners molesting you on the dance floor has limited appeal.’

Would Billy have preferred a cosy, soup-maker type of wife? From time to time I’m quite sure he would, but that’s not me. Anyway, he’d hate to have a mate who intruded too much on his daily life. Yes, Billy has become more and more of a hermit. Sometimes I think he’s a budding Howard Hughes. If I visit him in a foreign city where he’s been working for a while I am usually appalled by the state of his hotel room; he just hates letting people in to tidy up. I dare not touch his stuff – his drawing materials carefully laid out, his crossword puzzle beside the bed awaiting inspiration about thirty-two down, his brightly coloured underpants hanging in the shower, his banjo leaning precariously against the bathroom door. I swear he’d let his fingernails and beard grow to disgusting lengths if the various make-up artists he works with did not intervene for professional reasons. He might as well buy some planes, design a bra, and be done with it.

At least Billy and I don’t have a relationship like that of a friend’s grandfather who, when asked how many sugars he liked in his tea, replied irritably: ‘Och, I don’t know. Ask your granny.’ No, we spend too much time apart to become that enmeshed. But despite the travelling both our jobs require, we stay very much in touch. Yesterday afternoon, sitting in New York, I phoned Billy in Manchester. ‘I had the concert of my life tonight,’ he crowed. ‘What exactly made it so?’ I asked. ‘Oh, I just walked on, strode downstage, faced them, and just went for it.’ No one can analyse what Billy does, least of all him. Turned out the crowd at the Manchester Apollo had been treated to a favourite story of mine, about the time he went with a couple of mates to visit a friend in Glasgow. This no-frills bachelor cooked them breakfast, but there were no plates or eating utensils so he proffered food on a spatula. When one of them reacted uncomfortably to being expected to take a hot, dripping egg in his bare hand, he rebuked him with ‘Oh, don’t be so fucking bourgeois!’ Well, that’s the bare bones of the story, but Billy tells it in his idiosyncratic picturepainting style that brings the house down. ‘They loved it,’ he glowed. ‘Of course they did,’ I replied admiringly. ‘And how many times in your life have you felt you’d had the concert of your life?’ ‘About a dozen times,’ he replied. ‘Where?’ I asked, knowing full well I’d never get an exact answer. ‘Don’t know. It’s very difficult to tell. Tonight I was just in great shape with a great audience. Changing my mind. I suddenly thought to tell them about when you’re vomiting having had a curry, you find you’re an expert in African folk music. Then I did a thing about a drunk guy singing. He’s been thrown out of the pub and he’s standing on the street practising ordering drinks. But he gets fed up so he sings a song. Then I sang a new country song I wrote called “I’d Love to Kick the Shit Out of You”.’ See, it doesn’t sound funny when you put it like that, does it? Even Billy himself finds that a problem. He never writes down ‘material’ like most other comedians, but just before a show he tries to think of a list of things he might talk about. This only makes him more scared. ‘I think, “Fuck, I’ve got nothing!”’ he says.

Billy continues to be as nervous and anxious about going on stage as he was when I first met him. But, as he counselled me years ago when I was doing something similar, ‘You need your nerves.’ Once he gets on stage it’s a different story. He is still at his happiest under the spotlight. I still marvel every time I see him perform, watching the delicacy and ease with which he struts the stage. It’s truly magnificent. He would hit you if you used the word ‘technique’ to describe his comedy style, but the fact is he has one, and it’s genius.

Billy’s approach has altered little over the years, but there are some minor differences. Nowadays, he feels rather less tolerant of hecklers than he was when he first started. I believe this reflects the fact that he has matured as a performer to the point where he understands how annoying interruptions of any kind can be for other audience members – especially when they emanate from someone whose had a few too many. I remember when people used to stroll in and out of his show, to buy drinks or take a toilet break any time they felt like it, and it was enormously distracting for both Billy and audience alike. Fortunately, Billy has seen fit to slightly shorten the length of time he stands on stage – it used to be a marathon three and a half hours, so I suppose people needed to move around a bit. But even today, occasionally someone will start to shout incoherently. ‘Pick a window,’ Billy would say. ‘You’re leaving.’ Other deterrents included: ‘Keep talking so the bouncer can find you!’ or even ‘Does your mouth bleed every twenty-eight days?’ But backstage, Billy’s attitude is usually surprisingly benign. ‘Och,’ he shrugs. ‘They’ve heard CDs of my old shows. They think I like it.’

Over the years Billy’s performing style has become refined to the point where you think he’s simply talking to you in your living room, over a cup of tea, and making you howl. It’s effortless, seamless. He paints magical mind-pictures that force every last bit of air from your lungs leaving you gasping and sore of stomach. No one else in the world can do that. I’ve been watching him for thirty-odd years and I’m still a fan.

Billy says the best thing about being nearly seventy is not thinking about it. ‘But there’s something good about it when you’re upright,’ he confessed, ‘and when you look like me rather than one of those guys who’ve gone for the saggyarsed trousers.’ An anti-beige campaigner for many years now, Billy is proud of not looking like his father’s idea of an old man. ‘It’s nice to have hair,’ he boasts. ‘I’ve been very lucky with my genetics.’ One of Billy’s life ambitions was never to act his age. ‘Acting your age is as sensible as acting your street number,’ he says. ‘Acting the goat is much better.’

‘And another thing,’ says Billy, on a roll about the ageing process, ‘I seem to have gone off Indian a bit. Curry’s still my favourite food but I can’t eat it at night after a gig now.’ But he still keeps the toilet paper in the fridge just in case. Billy is also off Liquorice Allsorts. ‘I can’t stop until I’ve eaten the whole packet, so now I don’t start.’ He’s like that with Cadbury’s Chocolate éclairs and Tunnock’s Caramel Wafers, too, while understandably, broccoli remains the bête noir of his gastronomic realities. Oh, and he has never made friends with wobbly food. ‘Anything gelatinous is not to be trusted,’ he insists, ‘like aspic in pork pies. It’s a close cousin of snot. You shouldn’t be eating things you find in the wee corners of your body.’

For Billy, the worst thing about turning seventy is its transparency. ‘People feel duty-bound to remind you about it because your birthday is in the paper,’ he complains. ‘And my eyebrows seem to have taken on a life of their own.’ It’s true. Recently, Billy told me his spectacles were out of focus and that he thought he needed a new prescription for his lenses. Being a bit of a fashion maven, he has an impressive wardrobe of eyewear and he was exasperated at the thought of having to change all those glasses. Now, I’m no optometrist, but I did have the answer for this one. ‘Trim your eyebrows,’ I said. They were so unruly they were pushing his spectacles askew, thus blurring his vision.

Billy has come to love crossword puzzles. ‘What do you get from them?’ I asked. ‘The fact that I’m not dead yet,’ he replied. ‘It’s proof that my brain’s still alive. When I get a clue I go, “Yes! I don’t have dementia!”’ Word games were not so appealing to him in his earlier years; he had more sanguine passions. ‘What was your favourite decade?’ I asked. ‘When I was a teenager they invented rock ’n’ roll, so the Fifties were very good. The music was unbelievable – Little Richard, Fats Domino, Lonnie Donegan, Jerry Lee Lewis. We knew something had happened, and it wasn’t for your parents. It was for you. So I was listening to all this brilliant stuff and fancying women – wonderful.’ ‘What was the most fun you ever had?’ I asked, in vain hoping for some warm and fuzzy anecdote about the children and I. ‘Scoring a goal for a team called St Benedict’s Boys’ Guild,’ he replied, unabashed. ‘It was the only goal I ever scored playing for a team. I was an outside right, against a team called Sacred Heart. It was a real fluke – I shot at the goal and would have missed but the ball hit one of the players, bounced off him and went into the net. But I got it; I don’t give a shit how.’

Our conversation turned to religion. In the Epilogue of this book, Billy expounds his theory of the universe, and I was wondering if he had revised it at all. ‘Does the teacup theory still hold up?’ I asked. ‘Yes, more so than ever as a matter of fact,’ he said. ‘I really think I’m on to something. After I’m dead they’ll discover I was a seer. It’s perfection. See, the earth’s a virus or a disease, a wee cell in the scheme of all the greatness that surrounds it. That’s why I don’t believe any other planets are inhabited.’ The theory seemed to have become so complex, only Billy’s very special brain could comprehend it. I decided not to ask him to expand. Better just suspend disbelief and move on. ‘What do you think heaven’s like?’ I asked. Billy smiled happily. ‘In my idea of heaven there would be great music playing all the time,’ he said, ‘and Sandra Bullock would be wandering around, showing great interest in me. And that wee newsreader who used to be on breakfast TV in New York – the one whose husband died – she’ll be there.’

‘But, say you go to hell,’ I said sweetly, with only a soupçon of passive-aggression, ‘what would that be like?’ ‘Hmmm,’ he frowned. ‘A lot of my school teachers are there, and you have to do the nine times table every day.’ ‘And what would you do if you discovered the end of the world was in three days’ time?’ I asked. ‘Oh.’ Billy actually looked mildly excited about that possibility. ‘I would put on my favourite records – Bob Dylan, Hank Williams, John Prine, The Rolling Stones, and Loudon Wainwright – and have cups of tea and just … wait for the end. Now, if you were any kind of wife you’d realize that I’m horny and get your arse over here …’ Interview over.

Although Billy has long since turned his back on organized religion, he recently had the most profound spiritual experience of his life in a ‘sweat lodge’ when he was filming in northern British Columbia among the Nisga’a tribe. ‘The lodge is igloo-shaped,’ explained Billy. ‘It’s many layers of leather and canvas, and there’s a hole inside where the fire goes. The fuel for the fire is lava rock, which you have to gather yourself along with the medicine man. They make a big fire outside the hut, then carry in the rocks when they’re red-hot and place them in a pit. The medicine man sprinkles water on them to make the steam. First, you smoke a pipe of some herbs and waft sage over yourself. Then you have to crawl inside the small door to the lodge on your hands and knees. The idea of this wee door is that when you leave you’re like a baby reborn. The sweat lodge is your mother. Then we all sat in a circle around the fire pit. You can’t see a single thing. There’s a faint glow in the pit of lava, but you can’t see the others. You can only hear them, like spirits. It’s a bit like confession. The medicine man plays the drum, sings, and chants, and one at a time people unload things that are bothering them, or things they think they’d be better off without. I joined in. I was talking about being ungrateful. I felt that amazing good fortune had come my way over a period of many years, but that I took it for granted. I was not suitably grateful. The whole thing took around three hours. I didn’t think I could stand it after the first fifteen minutes, the heat was so intense, but I managed to regulate my breathing, and got to like it. It was a truly deep emotional experience. Afterwards, I found that I cried more easily than before. Tears would easily run down my face and I felt closer to myself. I recognized myself. They made me a member of the tribe. My name is something that sounds like “hissacks”, with a bit before that that sounds like alphabet soup. It means “Prince of Comedy”. And I’m a member of the killer whales. In the tribe there are wolves, salmon, killer whales, and bears. I’m a killer whale, an orca.’

For the first edition of Billy I asked my husband for his bucket list of things he wants to do before he dies. It was a terrible mistake to ask him for an update this year, because unfortunately he’s now got it into his head that he’d like to do a free-fall parachute jump out of an airplane on his seventieth birthday. But I’m afraid that would probably make his Route Sixty-Six mishap a walk in the park, so I’m hoping to dissuade him. He is also threatening to reinstall his nipple rings, which were removed for a shirtless scene during the filming of Mrs Brown and never replaced. ‘I kinda miss them,’ he says, ‘and I’m tempted to put them back in. But then I might have to wheek them out again …’

In fact, nipple rings would have been perfectly appropriate for some of Billy’s movie roles, especially the ‘hard man’ characters. He does love playing violent scoundrels, and particularly enjoyed being the gun-toting Irish crime family patriarch in The Boondock Saints and its follow-up, The Boondock Saints II: All Saints Day. He gave each one of our children the T-shirt of him with his bushy white beard, in his trench coat, cap, and shades, smiling wickedly with a smoking nine-millimetre Glock in each hand. The caption reads, ‘Daddy’s Working!’ Sick bastard.

Aside from playing savage Antichrists (to the point where really weird people approach him in American shopping malls to offer him silver bullets and Doomsday packs), Billy’s life ambitions, as revealed in the Epilogue, are largely unfulfilled. For example, he says he ‘might be a bit pissed’ that he has not yet made it to Eric Clapton’s fridge door (see page 411). But Billy’s main fantasy-ambition in life was to be a tramp. ‘I still look with great fondness on the idea of becoming a kind of colourful, American, country and western kind of hobo,’ he explains. ‘Most of my musical heroes were like that: Derroll Adams, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Alex Campbell, and Utah Phillips – he’s the one who said America is a big melting pot, but like all melting pots, the scum tends to rise to the top.’

Billy is still desperately hoping to wake up one morning and discover he’s Keith Richards. When The Rolling Stones played Glasgow as part of their most recent world tour, Billy and I drove down from the Highlands to see them. Before the concert, we were ushered to a backstage room where most of the band was engaged in a lazy game of billiards. Billy and I chatted to Keith for a while, and I embarrassed myself by being the only person on the planet who had not known the man had fallen out of a palm tree on some exotic tropical island. ‘What, you fell out of a tree?’ I echoed, when Keith referred to it. ‘Well,’ he muttered sheepishly, ‘it was more of a … shrub.’ At this point Billy was giving me his Evil Eye, which is the no-contact version of a Glaswegian kiss. ‘Well, anyway,’ said Keith, ‘I better say goodbye. Gotta go to makeup.’ Billy and I looked at each other. ‘What the hell are they going to do to him?’ I wondered aloud on our way to our seats. ‘Lip gloss?’ ‘Dunno,’ said Billy. ‘Forty years of heroin use can’t be powdered over … Does something irreversible to your skin. But he looks brilliant, doesn’t he?’ Billy glowed like a seminary novice who’d just seen the Pope. He had taken care to wear his skull ring just like Keith’s and, the second they met, they clicked rings together. ‘He was the first to wear those rings,’ said Billy, ‘well before they were trendy. And he liked my python cowboy boots! When he said that, my heart danced a wee jig!’ Seriously?

Regarding Billy’s fifth life’s ambition, to learn to sail, his manager Steve Brown presented him with a lovely boat called Big Jessie. Billy has had a few lessons but has yet to tame her. And as I discovered when I tried to engage Billy in my personal dream of spending the rest of our days aboard the sailboat Takapuna (on which I had many adventures from 2002–07, some of them shared by my husband), Billy is really not too fond of boats. ‘They’re like prison,’ he complains, ‘with the possibility of drowning.’ He recently learned to scuba dive, but considers being under the water with sharks (a favourite pastime of mine) ‘the best laxative known to man’.

The final item on Billy’s list is a strange one, because I believe he fulfilled that ambition from the moment he walked out of the shipyards: to change his mind as often as he damn well pleases. Perhaps Billy is unaware how self-determining he really is, although his family and work-mates certainly know. There’s hardly a person on this planet who would dare try to stop him doing something he’d set his mind to. Perhaps this was really a way to articulate his essential single-mindedness in a user-friendly fashion, a kind of Glaswegian gauntlet-throwing couched as a plea from a helpless dreamer.

I suppose it’s natural that, at this point in his life, Billy might reflect more and more on his time on earth. ‘What do you think your life would have been like if you hadn’t become a comedian?’ I once asked. ‘I think I would have been a welder,’ he replied. Then, as an after-thought, he said: ‘But I would have been a drunk one. And I would have been unhappy, because I always nurtured a wee dream I’d promised to myself.’ It is remarkable that Billy had a secret belief, even in his darkest days, that he would eventually find a way out and become successful. I suppose idiodynamism, the tendency of an idea to materialize into action, is what actually kept him going.

Although Billy sometimes complains about being on the road too much, I can’t see him retiring. He once foresaw his final years as those in which he would ‘sit on a porch playing the banjo and telling lies to his grandchildren’, but he is not really the type to settle into his rocker. He adores both his grandchildren (Cara’s son Walter has been joined by Babs since Billy was written) but, rather than lying, prefers to tell them truths – including ones their mother would rather they didn’t hear just yet. His five thriving children – Daisy, Amy, Scarlett, and (my stepchildren) James and Cara – are all old enough to laugh at their parents and remind them how ridiculous they are.

Since Billy was written, quite a few beloved pals have gone forever. The biggest loss for Billy was his long-term close friend Danny, whom he had known since their folk-singing days. ‘He was my best friend and I miss him,’ says Billy. ‘But he’s still in my show. I try to make a point of talking to the audience about travelling on the train with him, and playing practical jokes – like the time we started singing “Green Door” to a guy who was sleeping. We sang, “One more night without sleepin’ …” Danny was pretending to play the drums. “What’s that secret you’re keepin’ …” And when we got to “There’s an old piano, and they play it hot, behind the green door …” we screeched it at the top of our lungs, so the sleeping guy wakes up suddenly and takes off like a rocket, then collapses in a heap. “What’s going on?” he cried. We got uppity. “You gave us the fright of our lives! We were just about to summon a constable!”’

Several of Billy’s chums from his welding days are gone, too, including his pals Mick Quinn and Hughie Gilchrist. Billy’s long-term sound engineer Mal Kingsnorth died a few years back, and Billy sorely misses him. ‘I still wait for him to come to my dressing room after a show and give me a report.’ Billy’s Uncle Neil died in Scotland after a struggle with prostate cancer, while Billy’s former babysitter, Mattie Murphy, passed away a year or two ago in London, Ontario. Mattie had turned up to see Billy in concert in London several times over the years. He had always been so happy to see her sitting in the front row with her pal, all dressed up, smiling, and eager to see him.

Billy’s ex-wife Iris died in Spain in 2010. Their children Cara and Jamie had been sporadically in touch with their mother over the years. Billy had felt great compassion for her struggle with alcoholism and, although he had not seen her for many years, he was greatly shocked and saddened by her passing. ‘It didn’t really strike me till this summer when I put her ashes in the River Don and little Walter saw me crying,’ he told me. ‘Iris’s father had given her a wee book about Russia called And Quiet Flows the Don so I thought it might be nice to actually fl oat her there.’ Personally, I had not understood that Iris had suffered from a serious ‘hoarding’ disorder (we all learned this after her death), and felt very sorry that she had struggled so much without receiving the kind of psychological treatment that might have greatly helped her.

Billy’s former stage mate, the singer and songwriter Gerry Rafferty, passed away in 2011, after a long struggle with illness and alcoholism. Having been more or less alienated from each other for years, Billy was in touch with him throughout his final few months. He tried to help him in a number of ways, and felt enormously sad and helpless when Gerry’s decline proved inevitable. Those two were unstoppable in their day, a couple of highly talented pranksters with matching ambitions to make it as solo artists. According to Billy, they had enormous fun travelling around the country, womanizing, playing practical tricks on each other and navigating the unfamiliar landscape of show business.

Gerry’s passing had a profound effect on Billy. ‘I loved him very much when he died,’ said Billy. ‘I was texting him, and the sicker he got the more deeply I loved him and realized all the good he’d done me in my life. He was so helpful for my head, and the way I thought about myself. It gave me great pleasure to make him laugh when he was sick. I reminded him of some of the funny things we had done when we were performing together, and he was laughing on his death bed. I’m very, very proud of that. I saw him off and said my goodbyes properly, laughing on the phone. I knew that he knew I loved him. And he told me he loved me. He said I was the funniest man in the world. It was Gerry who made me think like an artist. He said: “What you do is art. You’ve got to think of it like that. So when you apply Oscar Wilde’s ideas, it’s for you, and not necessarily for everyone else. If you do it for yourself, that’s where you hit the heights.” When I lose control on stage and start laughing I’m at my happiest as far as the art goes. If I think it’s funny, it fucking is. It’s very selfish; I’m doing it for me. That’s what Gerry taught me.’

But how on earth did Billy, a welder in the Clyde River shipyards, manage to break out of the life he was expected to follow, leap onto the folk scene as a banjo player and singer with Gerry in The Humblebums, then segue into a comical banjoist, before his metamorphosis into Billy Connolly the stand-up comedian? And on top of that, how did he then find his way to American television, thence to some of the top film jobs Hollywood had to offer? Marry the prettiest cast member of Not the Nine O’Clock News? And now a visual artist no less? Astounding. I can only reiterate what I penned to end the original Introduction:

Billy’s real story is an utterly triumphant one. Not a day has passed since I met him thirty years ago without my shaking my head and marvelling at his miraculous survival of profound childhood trauma. His ability to sustain himself beyond those days is equally impressive, for once he was known to the world, another challenge presented itself: to survive the trauma of fame. Every person who comes to public attention experiences an alienation of self, the formation of a deeply unsettling chasm between his true inner self and his public persona. The danger lies not in the confusion of those two, as is commonly thought, but in the widening gulf between them. Fortunately, Billy’s survival skills ever sustain him. When I first asked the essential, penetrating question of how he always managed to summon the resources to turn trauma into triumph, I was hoping for insight and a lucid explanation. What I got was: ‘Well, I didn’t come down the Clyde on a water biscuit.’

The following is an attempt at a sensible answer.