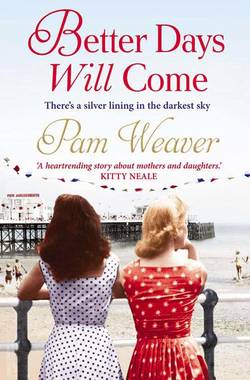

Читать книгу Better Days will Come - Pam Weaver - Страница 7

One

ОглавлениеWorthing 1947

‘Looks like they’re going to make a start on repairing the pier at last,’ Grace Rogers called out as she entered the house but there was no reply. She pulled her wet headscarf from her head and shook it. Water droplets splattered the back of the chair. She ran her fingers through her honey blonde hair which curled neatly at the nape of her neck and then unbuttoned her coat and hung it on a peg behind the front door.

She was a small woman, with a neat figure, pale eyes and long artistic fingers. She’d missed the bus and had to wait for another, so she was soaked. Someone had said that the Littlehampton Road was flooded between Titnore Lane and Limbrick Lane. She wasn’t surprised. The rain hadn’t let up all week. She kicked off her boots. Her feet were wet too but that was hardly surprising either. There was a hole in the bottom of her left shoe. Grace pulled out a soggy piece of cardboard, the only thing between her foot and the pavement, and threw it into the coalscuttle.

The two reception rooms downstairs had been knocked into one and the kitchen range struggled to heat such a large area. The fire was low. Using an oven glove, Grace opened the door and put the poker in. The fire resettled and flared a little. She added some coal, not a lot, tossed in the soggy cardboard, and closed the door. Coal was still rationed and it was only November 12th. Winter had hardly started yet.

‘Bonnie?’

No response. Perhaps she was upstairs in her room. Grace opened the stair door and called up but there was no answer. She glanced up at the clock on the mantelpiece. Almost three thirty. It would be getting dark soon. Where was the girl? It was early closing in Worthing and Bonnie had the afternoon off, but she never went anywhere, not this time of year anyway, and certainly not in this weather. Rita, her youngest, would be coming back from school in less than an hour.

Grace dried her hair with a towel while the kettle boiled. Her bones ached with weariness. She’d jumped at the chance to do an extra shift because even with Bonnie’s wages, the money didn’t go far. When Michael died in the D-Day landings, she’d never imagined bringing up two girls on her own would be so difficult. Still, she shouldn’t grumble. She was a lot better off than some. Even if the rent did keep going up, at least she had a roof over her head, and the knitwear factory, Finley International, where she worked, was doing well. They were producing more than ever, mostly for America and Canada. The war had been over for eighteen months and the country needed all the exports it could get. A year ago they had all hoped that the good times were just around the corner but if anything, things were worse than ever. Even bread was rationed now, and potatoes. Three pounds per person per week, that was all, and that hadn’t happened all through the dark days of the war.

Her hair towelled dry, Grace glanced up at the clock again. Where was Bonnie? She said she’d be home to help with the tea. She screwed up some newspaper and stuffed it into the toes of her boots before putting them on the floor by the range. With a bit of luck they’d be dry in the morning.

Grace brushed her hair vigorously. She was lucky that it was naturally curly and she didn’t have any grey. The only time she went to the hairdresser was to have it cut.

The kettle boiled and Grace rinsed out the brown teapot before reaching for the caddy. Two scoops of Brooke Bond and she’d be as right as ninepence. She was looking forward to its reviving qualities. She sat at the table and reached for the knitted tea cosy.

The letter was underneath. It must have been propped against the salt and pepper and fallen over when she’d opened the door and created a draught. Grace picked it up. The envelope was unsealed. Was it meant for her or Bonnie? And who had put it there? She took out a single sheet of paper.

A glance at the bottom of the page told her it was from Bonnie. Grace sighed. That meant her daughter was either staying over with her friend from work, or she’d decided to go to the pictures with that new boy she was always going on about. Grace didn’t know his name but it was obvious Bonnie was smitten. They’d had words about it last night when Grace had seen her with a neatly wrapped present in striped paper and a red ribbon on the top. Bonnie had sat at the table and pulled out a dark green jewellery box. Grace knew at once that it had come from Whibley’s, a quality jeweller at the end of Warwick Street. Although she had never personally had anything from the shop, they advertised in every newspaper in the town and the box was instantly recognisable.

Before Bonnie had even lifted the lid, Grace had stopped her. ‘Don’t even be tempted,’ she cautioned. ‘Whatever it is, you can’t possibly keep it.’

Bonnie looked up, appalled. ‘Why ever not?’

‘You’re too young to be getting expensive presents from men,’ said Grace.

‘Oh, Mum,’ said Bonnie turning slightly to lift the lid. ‘I already know what’s inside. I just wanted to show you, that’s all.’

Grace caught a glimpse of some kind of locket on a chain before closing the box herself. ‘I mean it,’ she’d said firmly. ‘You hardly know this man and I’ve never met him. How do you know his intentions are honourable?’

Bonnie smiled mysteriously. ‘I know, Mum, and I love him.’

‘Don’t talk such rot,’ Grace had retorted angrily. ‘You’re far too young …’

Bonnie’s eyes blazed. ‘I’m the same age as you were when you met Daddy.’

‘That’s different,’ Grace had told her.

They had wrestled over the box with Bonnie eventually gaining the upper hand, and thinking about it now made Grace feel uncomfortable.

She got a cup and saucer down from the dresser and sat down. As she poured her tea Grace began to read:

Dear Mum,

I am sorry but I am going away. By the time you read this, I shall be on the London train. You are not to worry. I shall be fine. I just need to leave Worthing. I am sorry to let you down but this is for the best. I shall never forget you and Rita and I want you to know I love you both with all my heart. Please don’t think too badly of me.

All my love,

Bonnie.

As she reached the end of the page, Grace became aware that she was still pouring tea. Dark brown liquid trickled towards the page because it had filled her cup and saucer and overflowed onto her tablecloth. Her hand trembled as she put the teapot back onto the stand. Her mind struggled to focus. On the London train. It had only been a silly tiff. Why go all the way to London? She glanced up at the clock. That train would be leaving the station in less than five minutes. She leapt to her feet and grabbed her boots. It took an age to get all the newspaper out before she could stuff her feet back inside the wet leather. I just need to leave Worthing. Why? What did that mean? Surely she wasn’t going for good. Her mind struggled to make sense of it. You’re only 18, Bonnie. You always seemed happy enough. Grace stumbled out into the hall for her coat. The back of her left boot stubbornly refused to come back up. She had to stop and use her finger to get the heel in properly but there was no time to lace them. As she dashed out of the door she paused only to look at the grandmother clock. Four minutes before the train was due to leave. Without stopping to lock up, she ran blindly down the street, her unbuttoned coat flapping behind her like a cloak and her boots slopping on her feet. Water oozed between the stitches, forming little bubbles as she ran.

There were lights on in the little shop on the corner of Cross Street and Clifton Road and the new owner looked up from whatever he was doing to stare at her as she ran down the middle of the road towards him. The gates were already cranking across the road as she burst into Station Approach. She could feel a painful stitch coming in her side but she refused to ease up. The rain was coming down steadily and by now her hair was plastered to her face. As she raced up the steps of the entrance, the train thundered to a halt on platform 2.

Manny Hart, neat and tidy in his uniform and with his mouth organ tucked into his top pocket, stood at the entrance to the station platform with his hand out. ‘Tickets please.’ If he was surprised by the state of her, he said nothing.

‘I’ve got to get to the other side before the train leaves,’ Grace blurted out.

He glanced over his shoulder towards a group of men, all in smart suits, walking along the platform. ‘Then you’ll need a platform ticket.’ Manny seemed uncomfortable.

Grace’s heart sank. Her purse was sitting on the dresser in the kitchen. ‘I’ll pay you next time I see you.’

But Manny was in no mood to be placated. ‘You need a ticket,’ he said stubbornly. The men hovered by the entrance, while on the other side of the track the train shuddered and the steam hissed.

‘You don’t understand,’ Grace cried. ‘I’ve simply got to …’ Her hands were searching her empty pockets and she was beginning to panic. She was so angry and frustrated she could have hit him. She looked around wildly and saw a woman who lived just up the road from her. ‘Excuse me, Peggy. Could you lend me a penny for a platform ticket, only I must catch someone on the train before it goes.’

‘Of course, dear. Hang on a minute, I’m sure I’ve got a penny in here somewhere.’ Peggy Jones opened her bag, found her purse and handed Grace a penny. As it appeared in her hand, Grace almost snatched it and ran to the platform ticket machine, calling, ‘Thank you, thank you’ over her shoulder. To add to her frustration, the machine was reluctant to yield and she had to thump it a couple of times before the ticket appeared.

The passengers who were getting off at Worthing were already starting to head towards the barrier as she thrust the ticket at Manny Hart. He clipped it and went to hand it back but Grace was already at the top of the stairs leading to the underpass which came up on the other side and platform 2. Now she was hampered by the steady flow of people coming in the opposite direction.

‘Close all the doors.’

The porter’s cry echoed down the stairs and into the underpass. The train shuddered again and just as she reached the stairwell leading up she heard the powerful shunt of steam and smoke which heralded its departure. She was only half way up the stairs leading to platform 2 when the guard blew his whistle and the lumbering giant was on the move. How she got to the top of the stairs, she never knew but as soon as she emerged onto the platform she knew it was hopeless. Through the smoke and steam, the last two carriages were all that was left. The train was gone.

Someone was walking jauntily towards her, a familiar figure, well dressed, confident and whistling as he came. He flicked his hat with his finger and pushed it back on his head and his coat, open despite the rain, flapped behind him as he walked. Norris Finley, her boss, was a lot heavier and far less attractive than when they were younger but he still behaved like cock of the walk. What was he doing here? Usually, Grace would turn the other way if she saw him coming but her mind was on other things. Throwing aside her usual reserve, she roared out Bonnie’s name. As the train gathered speed, she burst into helpless heart-rending tears, and putting her hands on the top of her head, she fell to her knees.

‘Are you all right, love?’ She heard a woman’s voice, kind and concerned. The woman bent over her and touched her arm.

‘Grace?’ said Norris. ‘You seem a bit upset. Anything I can do?’

Grace heard him but didn’t respond. She was still staring at the disappearing train, and finally the empty track. She couldn’t speak but she felt two arms, one on either side, helping her to her feet. Where was Bonnie going? Who on earth did she know in London?

‘Do you know her, dear?’ the woman’s voice filtered through Grace’s befuddled brain.

‘Yes.’ The man was raising his hat. ‘Norris Finley of Finley’s International,’ he said.

The woman nodded. ‘I’ll leave you to it then, sir,’ and patting Grace’s arm she said, ‘I’m sure it’s not as bad as you think, dear.’

Norris tucked his hand under Grace’s elbow and led her back down the stairs into the gloomy underpass.

‘She’s gone,’ Grace said dully when they were alone. ‘My Bonnie has left home.’

‘Left home?’

She was crying again so they walked on in silence with Grace leaning heavily on his arm. Norris winked as he handed his ticket to Manny Hart and steered Grace onto the concourse.

‘Is she all right?’ said Manny, suddenly concerned. He took off his hat and scratched his slightly balding head.

‘Mrs Rogers has had a bit of an upset, that’s all,’ said Norris pleasantly.

‘If you had let me go,’ Grace said, suddenly rounding on Manny, ‘I might have been able to stop my daughter making the biggest mistake of her life.’

Manny looked uncomfortable. ‘I cannot help that,’ he said defensively. ‘You know I would do anything for you, Grace. The men on the platform were government inspectors for when the railway goes national next year. Rules are rules and I have to obey.’

‘Mrs Rogers … Grace,’ said Norris. ‘You’re soaked to the skin. Let me take you home. My car is just outside.’

‘Your paper, sir,’ said Manny.

‘Eh?’ Norris seemed a little confused.

‘You dropped your paper.’ He handed him a rolled-up newspaper.

‘Oh, right,’ grinned Norris, taking it from him.

Manny watched them go.

‘Nice man, that Mr Finley,’ the woman remarked as she handed Manny her ticket and he nodded.

Outside it was still tipping with rain. ‘I’ll walk,’ said Grace stiffly. ‘It’s not far and I’m wet through anyway.’

There were still people waiting for taxis or buses. ‘Absolutely not, my dear Mrs Rogers,’ Finley insisted. ‘Hop in.’

As he climbed into the car, he handed her his folded handkerchief before they set off. He drove away like a madman but her mind was so full of Bonnie, Grace hardly noticed. She wiped her eyes and blew her nose. Outside her house, Grace turned to him. ‘She left me a note,’ she said hopelessly. ‘I found it when I got in from work.’

‘Where’s she gone?’

Grace looked up at him. ‘That’s just it,’ she said. ‘I don’t know. All she said was she had to leave Worthing.’

‘Had to leave?’ He raised his eyebrows and let out a short sigh. ‘Ah well, you can’t keep her tied to your apron strings all her life. She’s a sensible girl, isn’t she? She’ll be fine.’

Grace’s eyes grew wide. ‘Promise me you didn’t have anything to do with this?’

‘Of course I didn’t! Why should I?’

‘Why were you there then? What were you doing on the platform?’

‘I’ve been in Southampton on business,’ he said irritably.

‘Did you see her get on the train?’

‘No, but then I’m hardly likely to, am I?’ he said. ‘I travel first class. Does Bonnie travel first class? No, I didn’t think so, so why would I have seen her? Don’t be so melodramatic, Grace.’

Grace fumbled for the door handle but couldn’t open the door. ‘I didn’t expect any sympathy from you but Bonnie leaving like this … it’s breaking my heart.’

‘For God’s sake, Grace. Nobody died, did they?’ Norris said coldly. ‘She’ll be fine.’ He got out of the car and came round to the passenger side. Just as he opened the door Grace’s neighbour walked by under a large umbrella.

‘There you are, Mrs Rogers,’ Norris said loudly and cheerfully as he stepped back. ‘Back home safe and sound. Can I help you with your door key?’

Grace shook her head. The door was open anyway. She hadn’t stopped to lock it. She turned and he waved cheerfully as he got back into his car. He drove off at speed, leaving Grace standing like a dumb thing on the pavement.

‘You’ll catch your death of cold,’ said a voice. ‘You look soaked to the skin.’ Their eyes met and she hesitated. ‘You all right, Grace?’ Her neighbour who lived next-door-but-one, Elsie Dawson, was on her step putting her key into her own door. Dougie, her son, stood behind his mother waiting for her to open it. Elsie, her middle son Dougie and daughter Mo were good friends with Rita and Bonnie, and they had all enjoyed sharing times like Christmas and Easter together. Bob, Elsie’s oldest boy, was in the army now andMo was in the same class as Rita at school but Dougie was what the powers that be called ‘retarded’, a term which made Grace cross. He might struggle with understanding, but he wasn’t stupid. Once he knew what you wanted, Dougie would put his hand to anything.

‘I’m fine, thank you,’ Grace said with as much dignity as she could muster. But once inside the house, she sat alone on the cold stairs and gave way to her tears once again.

As the train sped towards London, Bonnie stared out of the window. She should have done this earlier in the day while she still had the opportunity. The light was going and by the time she reached Victoria station it would be dark. Never mind, George would be there to meet her. If for some reason they missed each other, he’d told her to wait by the entrance of platform 12.

She had finished work a lot earlier than she’d thought she would. The people in the wages department had worked out that she was owed a half day’s holiday so rather than give her the extra in her wage packet, she had been told she could go by ten o’clock. Seeing as how she had arranged to meet George in time for the train, it meant she had a couple of hours to kill. Her case was already in the left luggage department at Worthing and she couldn’t go back home, so she went to his digs.

Mrs Kerr, his landlady, was her usual unwelcoming self. ‘He’s not here,’ she’d said curtly, ‘and I have no time to entertain his guests.’ She had obviously taken her apron off to answer the door and now she was putting it back on again.

‘Do you know where he might be?’ Bonnie had asked.

‘He’s going to London.’

‘I know that,’ Bonnie had said. ‘I just wondered if he was still here.’

Mrs Kerr shrugged. ‘As far as I know, he’s gone to the old factory.’

Bonnie had frowned. ‘But why? It’s all shut up, isn’t it?’

‘All I know is he said he’d found something. Now I’m very busy.’

‘Do you know what he’d found?’ Bonnie persisted.

‘Am I my brother’s keeper?’ Mrs Kerr snapped as she shut the door.

Bonnie had stood on the pavement wondering what to do. There was still plenty of time before the train so she’d decided to walk to the factory. She didn’t have to go right into West Worthing. There was a Jacob’s ladder in Pavilion Road which was between the stations and came out at the bottom of Heene Road. Although she was wearing her best shoes, which were quite unsuitable for walking, it hadn’t taken her long to get to Finley’s Knitwear.

She had met George Matthews at a dance in the Assembly Hall. He was a friend of a friend and they’d hit it off straight away. He was so debonair, so handsome and so unlike any of her other friends that it wasn’t long before she was hopelessly in love with him. He worked at the knitwear factory in Tarring Road, the same as her mother. He was a machine operator, while her mum worked in the packing room. George was getting good money but he was ambitious so when it was announced that the factory would be moving to new premises, he felt it was time to move on.

‘I don’t think the boss is a very nice person,’ he’d told her. ‘Don’t let him get too close to you.’

‘Whatever do you mean?’ she’d asked, thoroughly alarmed.

He’d hesitated for a second then changed the subject. ‘There are real opportunities in places like South Africa, and Rhodesia and Australia, the sort of opportunities the likes of you and me will never get in this country. We can get away from all the corruption in high places. It’ll be a whole new start, far away from the war and everything to do with it.’

‘If Mr Finley is up to something,’ she’d asked, ‘should I say something to my mother?’

He’d shaken his head. ‘Your mother and all the other girls are safe enough if you keep your distance, but he’s deep, that one.’

Out of loyalty, he stayed long enough to help clear up the old place, but just lately he’d seemed even more troubled about something. ‘I’m glad we’re going,’ he said one day. ‘I really don’t want to work for Finley any more.’

Once again she’d asked why but he told her not to worry her pretty little head.

‘How will we get to South Africa?’ she’d asked.

‘Leave all that to me,’ he’d said mysteriously, and then he’d filled her imagination with sun-drenched beaches and cocktails before dinner and making their fortune. They’d made love in his digs at Pavilion Road. They had to be very careful for fear of his landlady who was a deeply religious woman, but while she was wrestling with the Devil at the prayer meeting every Tuesday night, Bonnie and George were wrestling between the sheets. And while Mrs Kerr studied the Bible every Thursday, they filled themselves with more carnal delights. Bonnie smiled cosily as she remembered those wonderful nights together.

‘Tickets please.’ The conductor on the train brought her back to the present day and Bonnie handed him her ticket.

When she’d told him about the baby, George had been wonderful about it. That’s when he had bought her the locket. It was so beautiful she’d vowed to wear it all the time. He’d said she should get a job until it was time for the baby to be born and then they would set sail. Having a baby in South Africa wasn’t as safe as here in England. He’d promised to get her passport all sorted and she’d saved up the £2 2s 6d she needed. The last thing she’d done as she’d left the house was to remember to take her birth certificate. Bonnie couldn’t wait. It was so exciting.

‘I shall need references,’ she’d told George.

‘I’m sure you can get someone to vouch for you,’ George said, nibbling her ear in that delicious way of his. ‘I think you’re a very nice girl.’

She’d giggled. He had a way of making her feel that it would all work out. Right now everything was such a mess but once they were married, it would be all right. She was sure of it.

She had decided to ask her old Sunday school teacher to give her a reference. She didn’t really know why, but she trusted Miss Reeves absolutely. She didn’t tell her everything, of course, but then how could she? It was easier to be economical with the truth although it did make her feel a bit guilty. Still, it wasn’t as if she was lying to the vicar or something. All she did was tell her just enough for Miss Reeves to write a glowing reference addressed ‘To whom it may concern’.

‘I know the woman you’ll be working for quite well,’ George assured her when he gave her the slip of paper. ‘Mrs Palmer is a nice woman. You’ll like her.’

Bonnie frowned. ‘How do you know her?’

He’d pulled her close. ‘Don’t I know just about everyone who’s anyone, silly?’

When she had surprised him at his digs after the row with her mother last night, he had taken her to his room. ‘You’ll get me thrown out onto the street,’ he’d said and she’d laughed. ‘Who cares? We’re going to live in South Africa,’ she’d said, her cornflower-blue eyes dancing with excitement.

George had drawn her down onto the bed with a kiss. Bonnie closed her eyes as she relived the moment. He was so good looking, so strong, so manly … She sighed. She hated doing this to her mother but she had to. If she’d told her mother what she and George were planning, she would have talked her out of it. Grace was a good mother but she still thought of Bonnie as ‘her little girl’. Bonnie smiled to herself. If only she knew. She certainly wasn’t her little girl any more. Since she’d met George, she had become a fully-grown woman.

When her father had been killed in the D-Day landings, Grace Rogers had been totally lost without him. The day the telegram came, she’d sat on the stairs, hardly even aware that she had two daughters to look after. Rita was the only one able to pacify her and they sat crying together. Without their father, life had become so difficult. They never had much money even though her mother worked all the hours God gave. Bonnie knew her mother would be upset to lose her wage, but it was all swings and roundabouts. There would be one less mouth to feed and Bonnie was determined she’d send a bit of money as soon as she and George were settled in South Africa. Of course, she would write to her mother long before they got there and once they were there, Grace could hardly refuse her consent to their marriage.

Bonnie stared at the name and address on the piece of paper she had been given. Mrs Palmer, 105 Honeypot Lane, Stanmore. Telephone: Stanmore 256. She couldn’t wait to see George at the station. Everything was going to be absolutely fine, she just knew it. With a smile of contentment, Bonnie leaned her head against the carriage window and closed her eyes.

Rita was puzzled. When she’d arrived home from school after choir practice, she found her mother sitting in the darkness on the stairs. Rita could tell at once that she had been crying but she didn’t seem to be aware that she was wet through and shivering with the cold.

Rita sat down beside her. ‘Mum?’

Grace stood up. ‘I’m going to get changed.’ She knew Rita was wondering what was wrong but she didn’t look back as she wearily climbed the steep stairs.

There was little warm water in the tap and the bathroom was very cold, but Grace washed herself slowly. How was she going to tell Rita? She and Bonnie were very close, so close they might almost be twins rather than two years apart. Bonnie had left no note for Rita. The girl would be heartbroken.

As she crossed the landing, a thought struck her. What if Rita already knew Bonnie was going? Maybe they’d planned it this way together. Grace felt a frisson of irritation. How dare they!

By now, she was frozen to the marrow. Pulling out some warmer clothes, Grace dressed quickly; a dry bra, her once pink petticoat, and a blue cable knit jumper over a grey skirt. She sat on the edge of the bed to roll her nylon stockings right down to the toe before putting them on her foot and easing over the heel. Her clothes were shabby, the jumper had darns on one elbow and at the side, her petticoat had odd straps because she’d used one petticoat to repair another, and her skirt, which came from a jumble sale, had been altered to fit. The one luxury she allowed herself was a decent pair of stockings. She rolled them slowly up her leg, careful not to snag them on a jagged nail, and checked her seams for straightness. Fastening the stockings to her suspenders, Grace towel-dried her hair and pulled on her wraparound apron before heading back downstairs to confront Rita.

‘Something’s happened,’ said Rita as she walked back into the kitchen. ‘What’s wrong, Mum?’

‘Your sister has left home,’ Grace said, her lips in a tight line, ‘but of course you already knew that, didn’t you?’

Rita’s jaw dropped.

‘Left home?’ Rita looked so shocked, Grace was thrown. ‘Where’s she gone?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘What do you mean, you don’t know?’

‘Precisely what I said, I don’t know,’ cried her mother, her voice full of anguish. ‘I was so sure you’d know all about it.’

Rita seemed bewildered. Grace threw an enamel bowl into the stone sink with a great clatter. All the while that she had believed Rita knew about Bonnie, there was the hope that she could bully her whereabouts out of the girl. ‘Mum?’

For a few seconds, Grace stood with her back to her daughter, her hands clenching the sides of the stone sink, as if supporting the weight of her body, then she turned round. Rita was alarmed to see the tears in her eyes. Grace reached out for her but when Rita stood up, scraping her chair on the wooden floor behind her, she ran upstairs. Grace could hear her opening drawers, looking in the wardrobe and searching for the battered suitcase that they kept under the bed. As she listened, she relived every moment of her own fruitless search not half an hour ago. She opened the stair door and sat down. A moment or two later, Rita joined her and laid her head on Grace’s shoulder.

Rita chewed her bottom lip. Left home … Bonnie didn’t confide in her much these days, but Rita was sure she would have said something if she’d known she was going away. Was she ill or something?

‘Has she done something wrong, Mum?’

No answer.

‘When is she coming back?’

‘Darling, I’ve told you,’ Grace sighed. ‘I don’t know.’

Rita’s stomach fell away. She couldn’t bear it if Bonnie was gone. Sometimes Bonnie and her mother had words but neither of them held grudges. It just wasn’t their way. A sudden thought struck her. She lifted her head. ‘Shall I go and see if she’s at Sandra’s place?’

‘She’s not at Sandra’s. She’s gone to London.’

‘London?’

‘She told me in a note.’

‘What note?’

Grace stood up and they both went back into the kitchen. She showed Rita the single sheet of paper.

‘I shall never forget you and Rita … it all sounds so final,’ said Rita.

Her mother couldn’t look her in the eye. She got the saucepan out of the cupboard, put it onto the range and reached for a couple of potatoes. ‘Let’s clear the table please.’

Rita gathered her schoolbooks into a pile. Tears were already brimming over her eyes. Why go to London? It was fifty miles away. Bonnie didn’t know anyone in London, did she? Rita opened her mouth to say something but thought better of it when she saw her mother’s expression.

‘There’s nothing we can do, love,’ Grace said firmly but in a more conciliatory tone. ‘Your sister has left home. I don’t know why she’s gone but it’s her choice and we’ll just have to get on withit.’

The potatoes Grace had cut up went clattering into the pan. She covered them with water before putting them on the range. Their eyes met and a second or two later, unable to contain her grief any more, Rita burst into tears and ran upstairs.

Victoria station was alive with people. Bonnie had arrived in the rush hour. She went straight to platform 12 as agreed with George, but after waiting a long two hours, she was so desperate for the toilet, she had to leave. She wasn’t gone for more than ten minutes but he must have come and gone during that time and she’d missed him. Why didn’t he wait? Where could he have gone? She didn’t know what to do, but she was afraid to move from their agreed meeting place in case she’d got it wrong and he was simply late. As time wore on, it grew colder. The station was getting quieter. She began to feel more conspicuous now that the evening rush hour was drawing to a close, and a lot more anxious. Oh, George, where are you? She scoured the heads of the male passengers, willing George’s trilby hat to come bobbing towards her, but it was hopeless. A few passengers who had obviously been to the theatre or some other posh frock do milled around, talking in loud plummy voices. Bonnie bit back her tears and shivered. She wished she and George could have travelled together but she hadn’t expected Miss Bridewell to let her go early. She’d worked her notice so that she could get the week’s pay owing to her and some of her holiday money. The extra money would come in handy if the job in Stanmore didn’t work out for some reason.

‘I’ve got on to a mate who can put us up,’ he’d told her. ‘Save a bit of money that way. He’s not on the telephone so I’ll go up and make the arrangements beforehand. I’ll meet you at platform 12.’

She saw a party of cleaners emerge from a small storeroom and begin to sweep the concourse and then she noticed a man approaching. Bonnie looked around anxiously. Why was he coming her way? She didn’t know him.

‘Excuse me, Miss,’ he said raising his hat. ‘I couldn’t help noticing you standing there. Has your friend been delayed?’

Bonnie didn’t answer but she felt her face heating up and her heart beat a little faster. Oh, George, she thought, where are you? Please come now …

‘If you’re looking for a place to stay,’ he continued, ‘I know where a respectable girl like you can get a room at a cheap price.’

Bonnie looked at him for the first time. He was smartly dressed in a suit and tie. He looked clean and presentable. He looked like the sort of man she could take home to her mother but she didn’t know him from Adam and she had read of the terrible things that could happen to young girls on their own in London in Uncle Charlie Hanson’s News of the World. She turned her head, pretending not to have heard him.

‘Forgive me,’ he smiled pleasantly. ‘I only ask because I can see you look concerned. I don’t normally approach young women like this.’

Bonnie began to tremble. Oh, where are you, George …

‘Could I perhaps offer you a cup of tea in the tea bar?’ He was very persistent but that was what the News of the World said they were like. Men like him duped girls into going with them and corrupted them into a life of prostitution.

She shook her head. Even though she was tired and sorely tempted, Bonnie didn’t go with him. She had seen the man watching her from behind a pillar for some time and she didn’t like it. She picked up her suitcase and walked towards the newspaper vendor to buy a paper.

Eventually she stopped a passing policeman and after explaining that she had missed her friend, he at first directed her, then, having heard her story about the man who kept pestering her, decided to walk with her to a small hotel just around the corner. Bonnie booked a room for the night. It wasn’t until she got undressed that she realised that the locket George had given her was no longer around her neck. Her stomach fell away. Where had she lost it? Had it come off when she was in that horrible factory? What a ghastly day it had been. Everything was going wrong. Bonnie climbed into bed and cried herself to sleep.