Читать книгу A Devil Comes to Town - Paolo Maurensig - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление-

What can prompt us to approach the difficult task of re-examining the many useless items that we’ve accumulated over the years and never found the courage to discard? An upcoming move maybe, or—as in my case—the need to clear out a room, till now a repository for worthless junk, so it could be put to different use. I can’t think of any other reason. Before parting with an object, we think twice about it, and most of the time we choose to keep it, convincing ourselves that it might be useful again in the future. Meanwhile things pile up until we are forced to make a clean sweep. Then we begin a journey back in memory: we browse through our past, we pause to gaze at old photos, to reread letters that we don’t remember having received, books with dedications, manuscripts … and I had stacks and stacks of those: since the publication of a fortuitous novel had afforded me a certain renown, I had become a pole of attraction for aspiring writers. Their manuscripts started coming with impressive regularity, the authors all requesting that I not only read them but give them my authoritative opinion, and possibly introduce them to some publisher, perhaps with the addition of a preface written in my hand. At the beginning I would take the trouble to read the texts through to the end, but I quickly realized that I would never be able to keep up, and that I would be spending most of my time on works of little or no interest. Getting rid of them, however, isn’t so easy: if it already pains me to have to part with an object, no matter how useless it may be, there is a certain regard for the author that each time stops me from disposing of the manuscripts. Consequently, I wanted to make sure I hadn’t made any error of assessment before sending them to be pulped. As I sat there flipping through one manuscript after another, I came across a large manila envelope, still sealed, amply covered by a mosaic of stamps from the Helvetic Confederation. I tore open the flap and found myself holding a text of roughly a hundred typed pages. There was no letter attached, nor was there a sender’s name, or a return address to be traced. Evidently the author wanted to remain anonymous. Or perhaps he meant to reveal himself in the course of the reading.

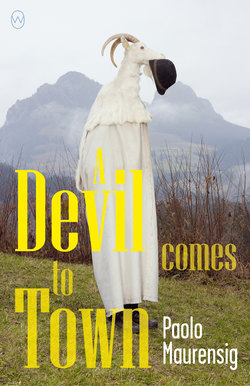

The title was: The Devil in the Drawer, and it began like this:

I tremble at the mere thought of having set this story on paper. For a long time I held it inside me, but in the end I had to unburden myself from a weight that threatened to compromise my mental equilibrium. Because it is certainly a story leading to the brink of madness. Yet I listened to it through to the end, without ever doubting the words of that man. All the more so because he was a priest.

I can understand that to the reader’s eyes all this has the appearance of a narrative device; literature is full of manuscripts, diaries, letters, and memos found in the most unexpected places and in the most unforeseen ways. But when you think about it, all stories begin by being drafted or printed on paper; everything we read begins with a ream of sheets, or rather, a manuscript, one of the many that pile up on a publisher’s desk or that of whoever is responsible for reading them for him. There was nothing extraordinary, therefore, in the discovery of this one: that bundle of pages was in the right place, only it had escaped my attention. The only thing strange about it was the anonymity.

The incipit seemed promising. And so, sitting right smack in the middle of all kinds of tattered texts, leaving my clean-up work half finished, I went on reading.

Though the author avoids revealing his name, he nevertheless sets the scene for the beginning of his story by specifying the date and location. It all goes back to September 1991, during a brief stay in Switzerland, specifically in Küsnacht, a small town that overlooks Lake Zurich, where our author traveled to attend a conference on psychoanalysis.

I was there as a consultant for a small publishing house that wanted to include in its catalog a series dedicated to this fascinating as well as controversial subject. Put that way, one might think that I played an important role. In reality, the publishing house belonged to my uncle who, already the owner of a typography shop, after having printed thousands of volumes on behalf of third parties, had been seized by the sudden ambition to become a publisher himself, hiring me more out of familial obligation than for any recognized merits.

A few words to tell us something about himself. He immediately reveals his condition as an orphan: his mother died giving birth to him, his father passed away a few years later, the victim of an accident on the job, and he himself was raised by his paternal uncle. We also discover that he is devoured by a passion for writing, and thanks to these disclosures, we are able to attribute an age to him: rather young, one would say, around twenty-five or thirty. Speaking in the first person, the author has no need to reveal his name, but to avoid unnecessary circumlocutions, I will assign him one. I will call him Friedrich: a name that I feel suggests a pale, blondish, aspiring writer rambling through the valleys of Switzerland.

Speaking of his uncle, Friedrich says and I quote:

Books were the only thing we had in common: he aspired to publish them, I to write them. In fact, I found myself in that blessed larval state that we all pass through as soon as we discover (or delude ourselves) that we are called to one of the arts. For a certain time, I had been the errand boy at a local newspaper in exchange for a wage that was barely enough for cigarettes. I edited the obituary page and occasionally minor news briefs. I had published a short story or two in that paper, just to fill up the page. If there was a scarcity of news and some free space still remaining, the editor-in-chief would then have me dash off a little narrative no longer than 700 words. So, I had never written anything that went beyond the short story, never published except on the pages of that provincial newspaper, but deep within me I nurtured a dream; I endured that fallow period waiting for a seed sown in the ground to sprout, until before long it might reach the size of a lush, fruit-bearing plant.

When I was later hired by my uncle in the publishing house, with the job of reading manuscripts and correcting page proofs, I felt like I had taken a step forward. I lived surrounded by books, breathing in the scent of printers’ ink that to me was as intoxicating as a drug. I assumed the airs of a writer, with a notebook and pencil always in my pocket, ready when needed. I observed people, trying to read in each of them his individual story … and yet I doubted that anyone would ever think of telling it to me someday. In any case, I had a permanent job in a publishing house and, though it was poorly compensated, I held on tightly to it. And this was my first important out-of-town mission. My uncle had assigned me this task thanks to my command of the German language—though it has little similarity to the local parlance.

Carl Gustav Jung had lived and died in Küsnacht, and that year, on the occasion of the thirtieth anniversary of his death, there was a three-day conference that involved experts from all over the world. Listening to the speakers, famous in their circles but to me completely unknown, I might perhaps come upon some text to publish, one not too pretentious, thereby inaugurating the new editorial series. Possibly I would not find anything of interest, and if that were the case—so be it!—I would enjoy a brief vacation at the company’s expense.

I had not thought about booking a hotel, so I had to settle for staying at the Gasthof Adler, a clean, quiet inn, somewhat out of the way. An ideal place to write, I immediately thought—at that time I assessed everything with the eye of an ambitious writer. The inn was a few kilometers from the town center, where the conference was being held in a municipal auditorium. There was a postbus that came by every hour, but even on foot it wasn’t a very long walk, and if you wanted to shorten it, you could take a path that cut through a dense fir wood. The weather was beautiful, the lakeside air invigorated the lungs, and in the sunlight the palettes of the rosebushes that adorned every house—from the villas to the more modest dwellings—were an enchantment for the eyes. So, that morning I had decided to go on foot. I could not yet know that something would soon cloud the idyllic image that I had formed of the place. It was an encounter that took place under peculiar circumstances. I was walking toward town along the path that went through the woods, when all of a sudden I heard a scuffling coming from the underbrush. I stopped, curious. My first thought was that some frightened animal—perhaps a deer—would suddenly dash out in front of me. Instead, I soon saw that it was a man whose body was so enormous that he appeared misshapen. Wearing a split leather smock, he was stumbling through the trees holding a plastic bucket filled with a reddish pulp and flinging handfuls of it on the ground. When he became aware of my presence, he looked up at me: the receding chin and drooping lower lip made me think of a mentally retarded person who had been assigned a task that no one else would want to do. As soon as he saw me, the man waved his arm as if warning me of some danger. What was he trying to tell me with that gesture? I continued along the path gripped by a growing sense of unease, as if I had trespassed on private property. I wanted nothing more than to get away from that place as soon as possible and reach the village. I must have walked a few hundred meters, when I heard the hurried step of someone behind me who was going in my direction. For a moment I thought it was the man I had just seen going through the woods, but the pace was too agile and swift for a person of his girth. I kept going straight and only turned around at the last moment, when the stranger was about to catch up to me. I immediately felt a sense of relief when I saw that it was a priest. A Catholic priest: complete with cassock and wide-brimmed saturn. Small and somewhat bent—just as I had always pictured Father Brown—, he came alongside me with a quick step and, after greeting me briefly, promptly warned me. “Watch out for the foxes,” he said excitedly, “don’t let them come near you: there’s an epidemic of wild rabies going around.” Having said that, he went on his way, quickly leaving me behind before disappearing around the first curve of the winding path. He seemed in such a hurry—as if the devil were literally on his heels—that it made me fearful of imminent danger. I was at the point where the woods grew more dense and the tops of the taller firs obscured the pale disk of the sun. It may have been suggestion caused by that strange warning, but I suddenly felt as if I was about to have a panic attack. I picked up a sturdy dead branch, ready to defend myself if needed, and started running in a vain attempt to reach the priest who, with his sprinter’s pace, had by then vanished. Gradually, however, as the first houses and the dazzling glimmer of the lake appeared through the firs, I regained my control.

Friedrich, therefore, reaches the village, where everyday life unfolds in an orderly and peaceful manner. In the midst of all that normalcy, he smiles at the thought of having been the victim of irrational fear. What has just happened to him seems almost unreal. Soon enough he convinces himself that it was just a trick of the imagination. He enters the conference hall and takes a seat in one of the few chairs still free. For a few minutes he absently follows the talk already underway: a bombastic excursus on Jung’s life. Then, among the numerous bearded professors with their flowing white manes—some with an unlit pipe between their teeth—, he spots the small Catholic priest he’d just met in the woods, sitting a dozen or so rows further up. He soon finds out that the cleric is one of the speakers. When the talk in progress ends, in fact, the priest takes his turn at the lectern. Friedrich consults the program he has in his pocket. It is the last talk of the morning, and will end at noon. At that precise moment the town hall clock strikes ten, and with Swiss punctuality the floor passes to Father Cornelius—that was the priest’s name—whose talk is entitled: “The Devil As Transformist.” So that explained all that hurrying, thinks Friedrich, evidently he was worried about being late for the conference: a failing that the audience members would have considered unforgivable.

The cleric addresses the problem of evil and its emissary with various digressions into the world of art and literature, in order to arrive at a particular point of view, namely, the notion of a devil incarnate who blends in among people and can play multiple roles, at times assuming the identity and appearance of apparently normal individuals, with whom we have daily personal relationships … No sulfur fumes, therefore, but the ordinary quotidian. The priest’s theory soon provokes divergent opinions. A theme so “secular,” put forth in that shrine of the psyche in an almost disarming way by a little country priest, can’t help but raise some sardonic comments, to the point that some leave the room protesting. To Friedrich, however, the topic seems rather original, and could very well constitute a book; moreover, the exposition is clear and the language is within everyone’s reach, like that of a Sunday sermon. Friedrich listens to the priest eagerly, not missing a single word, and is more and more convinced that he has found what he was looking for. So he will not go back to his uncle empty-handed after all, and perhaps may even merit a fitting increase in pay. In his mind he can already see the priest’s spoken words printed on paper, covering numerous pages that pile up on his desk to form a volume; he can even picture the cover. Meanwhile, time has flown by: the two hours scheduled for the talk have elapsed and with admirable synchrony, at the stroke of twelve, Father Cornelius concludes his talk, met by tepid applause. Friedrich’s first impulse is to approach the priest, but he is swallowed up by a crowd that flocks toward the exit and is pushed out of the hall. Then, when the crowd has thinned out and he returns to the conference room, there is no longer any trace of the cleric.

Several pages follow in which Friedrich expresses his concerns to the reader. He fears, in fact, that he will not see the priest again, that once his talk was over, he may have left immediately. His attempts, at the conference’s secretarial office, to find out where the cleric is staying are also hopeless: faced with the obdurate recalcitrance of the local dialect, his polished German seems to have become an incomprehensible foreign language. So for the entire afternoon Friedrich roams around the village in the hope of running into Father Cornelius, until toward evening he decides to return to the inn. He is tired and disappointed, and also famished. He knows that the Gasthof Adler’s kitchen closes at a certain time, and after having skipped lunch, he doesn’t feel like going to bed without supper as well. But when he gets back, a surprise awaits him.

As soon as I entered the dining room, I saw him sitting in a corner, the only guest in there, intent on eating his meal. After looking for him in vain all day, there he was, Father Cornelius! It didn’t seem real. Thinking about our encounter along the path leading to town, I should have imagined that he too was staying at the Gasthof Adler, since there were, in fact, no other hotels or inns nearby. This time I would not let him slip away. Judging by what was still on his plate, I estimated I had enough time to attempt a conversation. I sat down not too far away, but he did not seem to notice my presence; he was completely absorbed in his thoughts, and occasionally his lips moved as if he were speaking to himself. That evening, as the last arrival, I had to settle for a cold platter accompanied by a pint of beer; for the moment it was enough to appease my hunger, however, since my thoughts were wandering elsewhere. What was most urgent for me, in fact, was to find the right words to start a discourse. I was simply waiting for the right moment, which, however, never seemed to arrive. Both due to the presence of the waitress, who couldn’t wait to be able to clear the table, and the fact that the priest was in a totally different world, it became increasingly difficult to attempt a first approach. Several times I’d cleared my throat to say something, perhaps to praise his lecture, or remind him of our brief encounter in the woods. It wouldn’t have taken much, but each time something prevented me at the last moment. On the other hand, I didn’t stop observing him for one instant. It may have been due to the poor lighting in the room and the dark wood-paneled walls, but compared to the brilliant speaker I had heard only a few hours earlier, I now seemed to have a different person before me: a weary, frowning man, oppressed by his thoughts. By now he had emptied his plate, and I could only count on the time it would take him to down the two gulps of beer that still remained in his glass; a sip or two, after which he might well get up and go, leaving me in the lurch. I had to make a move. Suddenly, however, sensing that he was being watched, the priest looked up at me. He stared at me for a few moments, then gave a slight smile, a sign that he had recognized me.

“I hope,” he said, “that I did not alarm you too much this morning.” And not giving me time to reply, he went on: “Did you know that every year hundreds of thousands of people throughout the world die because of this terrible disease? Naturally, this occurs in areas far removed from civilization: in certain villages in Africa or Asia, too far from a hospital that could ensure timely treatment. These poor people are destined for an atrocious end, atrocious for themselves and for their family members, who can do very little to alleviate their suffering.”

I didn’t know what to say, so I threw out a question:

“And did you have the chance to witness one of these patients on his death bed?”

“It’s a sight that I would not wish anyone to see.”

For a moment the priest lowered his eyes, as if regretting what had slipped out of his mouth. He surely thought that he had to justify such a statement: “Rabies, which the fox is recognized as the main carrier of, arouses an atavistic fear in us, since it not only leads to a horrible death, but is able to bring out from human nature what we have always tried to conceal: the irrepressible viciousness that lies hidden in all of us. What’s more, the fox’s cry is chilling enough to make the most courageous person’s skin crawl. All this fuels popular superstition, which often associates the fox with the devil. And it’s truly a pity that such a charming little creature is forced to bear such a grim reputation.”

At that point the priest stopped short, as if realizing too late that he had been impolite to me: though I might seem like little more than a boy in his eyes, his having addressed me so abruptly did not fall within the rules of good manners. He tried to make up for it then: he got up from his seat, came over to me, and after the proper introductions he asked permission to sit at my table. I gladly agreed, and was able to observe him more closely. It was difficult to attribute an age to him; his face seemed pallid, his expression brooding, and his short, reddish hair still bore the indentation mark left by the ecclesiastical saturn …

“Are you here for the conference?” he asked.

With that question he made things easier for me, giving me the opportunity to brag a little.

“I’m a consultant for a publishing house,” I said. “I’m here hoping to find a text to publish in our new series. In fact, I have to say that when I listened to your talk today I found it very interesting. Your literary references: Goethe, Mann, Hoffmann, symbolist painting … At times though I had the impression that the things you left unsaid were more numerous than those you did say. It seemed to me that you were speaking about the devil as if he were a real existent being.”

“In fact that is the case. Only I couldn’t say it openly to an audience of psychoanalysts. I would likely have been subjected to analysis right then and there.” He acknowledged the weakness of his joke with a faint smile.

“Do you mean you’ve met him?”

“Of course,” the priest replied with great seriousness.

“Are you an exorcist by any chance?”

“Nothing of the kind. I’m talking about the devil-made-man, flesh and blood like me and you.”

“How can that be? I mean, a devil registered in the census, complete with name and surname, driver’s license and health-care card.”

The priest frowned.

“The one does not exclude the other. In fact for all intents and purposes he is a man: he is born of a father and a mother, almost always pious, decent people who accept the burden of such an offspring as expiation. Others, however, can’t tolerate it and manage to get rid of the devil when he is still in swaddling clothes. That’s why many of them are foundlings, children abandoned by their parents, not out of economic necessity, but for having manifested their malevolent nature from the very first days of their lives. And ultimately they are adopted by childless couples longing to have a baby. The devil thus exploits his parasitic position, and most of the time he causes his parents’ deaths, whether by a simulated accident or a broken heart, so he can inherit their possessions and dedicate himself to his own mission. A devil’s career, however, is not always crowned with success. Very often these subjects, whom we might rightly call poor devils, have a short life, and most times they end up behind bars where there are few opportunities to exercise their evil arts. On the other hand, many are born into legitimate, aristocratic families, who suspect nothing of their scions’ peculiar natures, often justifying and even encouraging their unseemly behavior, as if it were a mark of power. And these individuals procreate actual diabolical genealogies. We don’t know how many of them there are roaming around the world. Probably many more than we think.”

“And how can they be recognized?”

“There are signs that presage an evil nature. Recurrent signs that not everyone is able to recognize, however.”

“For example?”

“They are behaviors that are manifested from early childhood, such as a tendency toward excessive lying, or gratuitous cruelty toward animals. Of course, all children lie to avoid punishment, or because they live in an imaginary world, just as everyone has a legitimate curiosity to find out how a living creature is made inside, but when dissection becomes a habitual practice and its purpose is solely to inflict pain, in that case the child requires vigilance. Anyway, that’s the most obvious sign, but there are dozens of others that develop later on, which there’s no need to speak of. One says it all: the ability to make your thoughts turn against you.”

Father Cornelius seemed to search my face to study the effect of his statement. Reading a trace of skepticism there, he continued:

“First the Church, and later romantic literature, gave the devil prominence: they portrayed him in various ways, they gave him a face, a character, they provided him with a job, a mission, they clothed him in all kinds of attire, to the degree of making him visible, alive. In short, they humanized him.”

I wasn’t sure where he was going with this. I felt like I was listening to the ravings of a madman. In any case, I played along.

“So the devil was created in our image and likeness?”

“Precisely. There is nothing in the world that was not first conceived of by a mind, even before it existed. You write, I suppose …”

Taken by surprise, as if writing were a sin to be ashamed of, I felt myself redden: “Is it obvious by looking at me?”

“It’s not hard to see,” Father Cornelius replied with a smile, “and besides, last night I heard the clacking of a typewriter.”

It was true: the night before, right after supper, I had gone up to my room to make a clean copy of some notes scrawled in pencil in a notebook. I had typed a few lines on my old portable, but then, thinking it was too noisy for that quiet place, I had put it back in its case. But the fact that my secret passion was written on my face didn’t sit too well with me.

“I’m trying at least, with no appreciable results,” I replied, with some embarrassment.

“You are still young and have every possibility ahead of you. But be careful about the choices you make.”

“What do you mean?”

“Literature is the greatest of the arts,” the priest continued, “but it is also a dangerous endeavor.”

“In what sense, dangerous?”

“Each time we pick up a pen we are preparing to perform a ritual for which two candles should always be lit: one white and one black. Unlike painting and sculpture, which remain anchored to a material subject, and to music, which in contrast transcends matter altogether, literature can dominate both spheres: the concrete and the abstract, the terrestrial and the otherworldly. Moreover, it propagates and multiplies with infinite variations in readers’ minds. Without knowing it, the writer can become a formidable egregore.”

“Egregore? What’s that?”

The priest assumed a patient attitude.

“Today the meaning of the term has been greatly diminished. It means a chain reaction caused by univocal thinking. There is an exemplary tale about it: it is said that in an old friars’ monastery a gust of wind had lifted into the air a monk’s habit that had been laid out to dry in the sun. After a brief flight the garment glided like a kite to the bottom of a crag, getting tangled in the branches of a bush not far from the path that the friars took early in the morning on their daily walk. And each day, in the monks’ imaginations, that habit increasingly assumed the form of a man. Someone then suggested that it could be the devil, stationed at that spot to count souls. From that moment on, in the mind of the monks, the figure grew more and more menacing, until it took on material form and drove the whole monastery into a frenzy. And only the bishop’s intervention was able to make the devil go away and resume his earlier form: that of a mere bush. The writer, therefore, can initiate a chain of thought capable of attributing life and intelligence even to a figure everyone considers to be imaginary, such as the devil.”

At that precise moment we heard the front door of the inn open. Someone had come in, but from the spot where we were sitting we could not see him. Only his heavy steps could be heard treading the floorboards; evidently he was a customer who had stopped for a drink. For a moment the man appeared in the doorway of the dining room, his profile filling the entire space. Seeing him, I jumped in my seat. The man, in fact, was the same fellow I had run into in the woods, busily flinging that gory pulp on the ground. This time, however, his menacing figure was refined by a clean shirt, revealing a brawny neck, and a checked jacket that seemed to have been made out of a full-size bedspread. Since no one showed up, we heard him stomp out, muttering between his teeth. Father Cornelius looked me straight in the eye.

“Speaking of the devil …”

I burst into a nervous little laugh: “I ran across that man this morning.”

“His name is Hans,” the priest explained, “and he is the local veterinarian’s assistant. At this time he is assigned to perform a truly distasteful task.”

“The task of scattering … what? Poisoned bait?”

Father Cornelius shook his head: “Despite his appearance, Hans is a gentle, sensitive man, who loves animals very much—which makes his task doubly unpleasant: not only must he prepare that disgusting pulp with his own hands, but he must also obtain the raw ingredients.”

“Which would be?”

“Fox cubs.”

“You mean baby foxes?”

“He catches them in their dens and doesn’t hesitate to cut them into bits and pieces. To that end he always carries a cleaver and a wooden chopping board hanging from his belt. Only the smell of their murdered offspring keeps the rabid foxes away from the villages.”

Hearing those words I felt my stomach turn, but Father Cornelius didn’t seem to notice it and went on as if nothing had happened.

“A fox infected with rabies,” he said, “behaves strangely: he doesn’t run away at the sight of a man, but approaches him effusively until he is able to bite him. And so, too, the devil: his first strategy, in fact, is to become friendly with the designated victim. Therefore, the first rule of defense is to not let yourself be deceived by appearances. Nowadays the devil no longer has horns, nor a two-sided cape, he no longer smells of sulfur, he doesn’t frighten us with his façade, but rather he does everything he can to make himself seem helpful and agreeable. He doesn’t have, as one might think, the look of a huckster, nor of an eye-winking panderer, nor that of a jolly good fellow with an inexhaustible repertoire of spicy stories. His appearance is always well-groomed, he wears double-breasted suits, his speech is refined, his tone of voice persuasive. Except for one detail that escapes attention at the moment. Nonetheless it is perceived subliminally and makes him appear ridiculous. It’s like seeing a price tag still attached to the jacket of someone who prides himself on displaying a sophisticated elegance. But too bad for anyone who notices this detail, or rather, too bad if he is discovered to have noticed it, because this will send the devil into a rage, and then that individual will become his target. The devil is extremely touchy, in fact. Being the low man on the totem pole, on the bottom rung of the infernal hierarchy, he is thus even more motivated to get ahead; in other words, he is the prototype of the corporal who aspires to one day become the great general. But like all of us, even the devil has to come to terms with History and its changes. Owing to the progress of science and technology, the ground shifted beneath his feet, and before long he had to accept modernity, or rather, resign himself to not being up to the sudden changes in our century. These days the great stages of the past, with their fascinating sets exalting his figure, no longer exist; the imposing cathedrals are replaced by churches designed by less than mediocre architects, the grand theaters are as unadorned as parish chapels, and the somber castles, when not completely ruined, are invaded by noisy crowds of little brats, accompanied by parents who roam the halls with their Baedekers in hand and noses in the air. Given such a scenario, what’s left to the poor old-school devil? What does he have to do to avoid being outclassed by the new diabolical generations? By this time he is too old to be able to be refashioned—that’s right, because even the devil incarnate is accordingly subjected to earthly laws: he ages, he goes out of style, he loses his shine, he gets sick and finally dies, damned as he was at birth. The scope of his operations has been greatly curtailed, his magic tricks are now outmoded: the world of so-called spiritual power is out of his reach, as is that of financial power, which is now the prerogative of corrupt politics; what’s left to him, therefore, is merely power as an end in itself, that which is exercised in any human congregation where there is competition. It could be the neighborhood bowling league or the most exclusive Rotary club. But all the better if it is a pseudo-intellectual competition. Consequently, the ideal place is a literary society, not only because literature is the last locus of knowledge that still attributes him a certain credibility, but also because it is the place where vainglory, fueled by envy, grows immoderately, where even the most banal thoughts—as long as they are printed in type—are accepted as absolute truth.”

I was beginning to feel uncomfortable, because an activity dear to me, to which I thought I would devote myself entirely in the future, was under accusation.

“In your opinion, then, literature is bad?”

After his unexpected outburst, Father Cornelius composed himself and, having regained his calm, proceeded in a more even tone.