Читать книгу The Panda Theory: Shocking, hilarious and poignant noir - Pascal Garnier - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

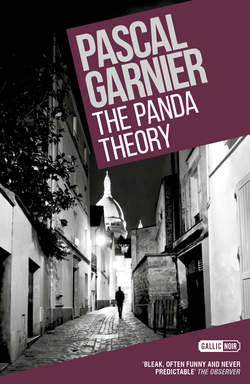

The Panda Theory

ОглавлениеHe was sitting alone at the end of a bench on a deserted railway platform. Above him, a tangle of metal girders merged into the gloom. It was the station of a small Breton town on a Sunday in October – a completely nondescript town, but certainly Brittany, the interior anyway. The sea was far away, its presence unimaginable. There was nothing picturesque here. A faint odour of manure hung in the air. The clock said 17.18. Head bowed, his elbows on his knees, he examined his palms. Hands always get dirty on trains, he thought. Not dirty exactly, but sticky, especially under the nails, with that grey grime that comes from others who have touched the handles, armrests and tables before you. He raised his head again, and, as if spurred by the surrounding stillness, stood up, grabbed his bag, walked a few metres back up the platform and took the underpass to the exit. No one crossed his path.

He used his teeth to tear open the plastic wrapper of the tiny tablet of soap then washed his hands thoroughly. The washbasin had two taps, which meant that he had to switch between the freezing water from the left and the scalding water from the right. He didn’t intend to look in the mirror but couldn’t help catching sight of himself as if he were an anonymous passer-by in the street. The waffle towel, staple of cheap hotels, was little bigger than a handkerchief. He looked around the room as he dried his hands. A table, a chair, a bed and a wardrobe containing a pillow, a moss-green tartan blanket and three clothes hangers. All made of the same imitation wood, MDF with a rosewood veneer. He flung the towel onto the brown patterned bedspread. The room was stifling. The radiator had just two settings, on and off. He had once disposed of a litter of kittens by shutting them in a shoebox lined with cotton wool soaked in ether. The miaowing and scratching had not lasted long. His bag sat at the foot of the bed like an exhausted dog, the handles flopping by its sides, the zip tongue hanging out. He yanked the curtain back and flung open the window. Still that manure smell. A streetlamp cast a pale glow over half a dozen lock-up garages with corrugated-iron doors of the same indefinable colour. Above it all, the sky, of course.

And, of course, the bed was soft. The frosted-glass lampshade overhead, clumsily suggesting some sort of flower in bloom, failed to brighten up the room. He switched it off.

‘Do you know anywhere round here to have dinner?’

‘On a Sunday evening? Try the Faro. It’s the second left as you go down the boulevard. I don’t know if they’re open though. Do you want the door code in case you come back after midnight?’

‘No need. I’ll be back before then.’

The receptionist was called Madeleine, or so the pendant round her neck informed him. She wasn’t beautiful, but not ugly either. Somewhere between the two. And very dark-haired; there was a hint of a moustache on her upper lip.

A few dark shops, like empty fish tanks, lined the street. A car passed in one direction, two in the other. There was no one on the street. The Faro was more of a bistro than a restaurant. Apart from the owner, sitting behind the counter with a pen in his mouth, engrossed in some calculation, it was empty.

‘Good evening. Are you open for dinner?’

‘Not tonight.’

‘Ah, well, in that case I’ll have a Coke. Actually, no, a beer.’

Off his stool, the man barely measured five foot four. Stocky with bushy hair, he resembled a wild boar but with doe eyes and long curling lashes. The man pulled a beer, gave the counter an automatic wipe, and placed the drink on the bar.

‘I usually do food, but not tonight.’

‘Too bad.’

The owner stood awkwardly for a moment, his eyes lowered, busying himself with his cloth, and then returned abruptly to his stool behind the till.

Other than the four brass lamps illuminating the bar, the rest of the bistro was in total darkness. Probably because there weren’t any other customers. You could just make out the tables and chairs and, in the back room, children’s toys: a pedal tractor, building blocks, Lego, an open book, sheets of paper and scattered felt tip pens.

He didn’t touch his beer. Perhaps he didn’t really want it.

‘Were you after food?’

‘Yes.’

‘My wife does the cooking. But she’s in hospital.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that.’

For a moment, the only sound in the bar was the fizzing of the beer’s froth.

‘Do you like salt cod stew?’

‘Yes, I think so.’

‘I was about to close. There’s some left, though, if you like.’

‘That sounds great.’

‘Well, take a seat. No, not here, come through.’

The back room erupted suddenly in a blaze of lemon-yellow fluorescent light. The two men picked their way over the pedal tractor, the building blocks, the Lego bricks and the brightly coloured children’s drawings.

‘You can sit there.’

He sat down at a table covered with a daisy-patterned apple-green oilcloth, facing a huge television.

‘I won’t be a sec,’ said the owner. Before leaving the room he pressed a button on the remote. The TV screen spewed a stream of incoherent images and gurgling sounds, like blood bubbling from a slit throat.

… BUT THE FINAL DEATH TOLL IS NOT YET KNOWN. IN NORTHERN IRELAND …

‘Bacalao!’

The owner placed two plates heaped with salt cod, potatoes, peppers and tomatoes on the table along with a bottle of vinho verde.

‘Bon appétit!’

‘Thank you.’

… THE PARENTS HAVE ISSUED A MESSAGE TO THE KIDNAPPERS. INTERVIEWED EARLIER …

‘My wife, Marie, makes it, but I’m the one who taught her. I’m Portuguese, she’s Breton. All she could cook was pancakes. She still makes them. You’ve got to make crêpes in Brittany! Are you a Breton?’

‘No.’

‘I thought not.’

‘Why?’

‘A Breton downs his glass in one. But you haven’t.’

‘Is it serious?’

‘What? Not being a Breton?’

‘No, your wife.’

‘No, it’s a cyst. She’s tough. She’s never been ill before. I drove her to the hospital this morning. The kids are at their grandmother’s. It’s best for them.’

… NO ONE WAS KILLED IN THE ACCIDENT. FROM OUR CORRESPONDENT IN CAIRO, LAURENT PÉCHU …

‘How many do you have?’

‘Two, a boy and a girl, Gaël and Maria, seven and five.’

… IT COULD JUST BE HUMAN ERROR …

‘How about you? Do you have any children?’

‘No.’

‘Are you a sailor?’

‘No.’

‘I only ask because of your reefer jacket.’

‘It’s practical.’

… AT HALF-TIME, THE SCORE WAS 3–2 …

The salt cod hadn’t been soaked for long enough. He didn’t like the vinho verde. He would have preferred water, but there wasn’t any on the table. He only had to ask. The owner would have given him some, like the beer he had not drunk. Stupid.

‘Do you know Portugal?’

‘I’ve been to Lisbon.’

‘What a beautiful city! It’s huge! I’m from Faro myself. It’s also pretty, but smaller. I came to France in ’77, to Saint-Étienne, as a builder. And then …’

… TRIUMPH AT THE OLYMPIA. LET’S HEAR WHAT THE FANS ARE SAYING …

‘… I left the building trade to open the restaurant with Marie. Would you like coffee?’

‘No, thank you.’

‘Okay.’

… OVERCAST BUT WITH SUNNY SPELLS IN THE LATE AFTERNOON …

‘That was very tasty. How much do I owe you?’

‘Ten euros? I won’t charge for the beer.’

‘Thank you.’

… WONDERFUL EVENING AND STAY WITH US HERE ON CHANNEL ONE …

‘I thought I’d be eating alone tonight. I’m José by the way. And you are?’

‘Gabriel. See you tomorrow.’

‘Yes, tomorrow, but as long as Marie is in hospital I’m not opening the restaurant.’

‘That’s fine.’

‘Do you have a fridge?’

‘Er, yes.’

‘Could you put this in it until tonight?’

‘What is it?’

‘Meat.’

‘Of course, that will be fine.’

‘Thank you.’

The hint of moustache on Madeleine’s lip was effaced by her warm smile as she took the five hundred grams of boned lamb shoulder. Anyone watching would have found the scene somewhat biblical. Today, Madeleine looked beautiful.

The flimsy wire hanger was designed for summer outfits and it sagged pitifully under the weight of the wet reefer jacket. It had been raining since early morning, a light rain that was perfectly in keeping with the town and gave it a certain elegance, a veneer of respectability. Gabriel had delighted in it from the moment he had opened his eyes; it was like a kind of salutary grief, an unobtrusive companion, an intimate presence.

There were people about, mothers taking their children to school and housewives weighed down by bulging shopping baskets. Mainly women. The men were digging holes in the road and replacing the rotten, rust-eaten pipes with new grey plastic ones. They seemed to revel in making a lot of noise and wheeling their big orange diggers in and out of the pus-yellow mud. It was a typical Monday. The shops showed off their best wares with the clumsy vanity of a girl getting ready for her first dance: bread, flowers, fish, funeral urns, medicines, sports equipment, houses for rent or sale, every kind of insurance, furniture, light fittings, shoes and so on.

He had tried on a pair of shoes just because the shop assistant seemed bored all alone in her pristine shop. But he had not bought them. He had apologised, saying that he was going to think about it. Not a sale, but a glimmer of hope at least. It didn’t take much to make people happy.

After that he had stopped at a café for a hot chocolate and found himself sitting next to two young men in ill-fitting suits who talked business with the seriousness of a pair of children playing at being grown-ups. From what he could gather, their problem was how to get rid of two hundred pallets of babies’ bottles and as many unfortunately incompatible teats.

‘Africa. It’s the only way …’

On leaving the café he had found himself outside the butcher’s gazing longingly at a rolled shoulder of lamb garnished with a cute sprig of parsley. It made him think of baby Jesus.

The radiator continued to pump out a suffocating heat. He felt overcome by a kind of tropical fever. The bed morphed into a hammock and a mangrove swamp of memories closed in on him, incoherent, tangled.

There had been toys scattered about the empty house there as well.

‘You can see, can’t you, Gabriel, she had everything. EVERYTHING!’

His friend Roland made a sweeping gesture that encompassed the vacant space. It still smelt of fresh paint.

‘You can’t tell me we wouldn’t have been happy here!’

Gabriel had not been able to think of a response. He had merely shaken his head. It was sadder to see it like this, virtually unlived in, than it would have been if a bomb had hit it. Nadine, Roland’s wife, had left with the kids barely a week after moving in. Everything was achingly new. Most of the furniture was still wrapped in plastic.

‘“I don’t like chickens.” That was her only explanation! Christ! She could have said earlier! I could have kept pigs. Or something else. You’ve seen the sheds, haven’t you? They’re a long way from the house. You can’t smell them. Or hear them. A farm with two thousand chickens, the very best, state of the art! I’d have paid it all off in ten years! You’ve seen it, Gabriel; it’s impressive, isn’t it?’

He had seen it. Roland had shown him around. It was awful. He couldn’t help but be reminded of a concentration camp. Two thousand albino chickens under ten metres of corrugated-iron roofing, fluorescent lights glaring day and night, the birds clucking and tapping their beaks like demented toys. And an appalling sickly smell, which the ambient heat only made worse. He had hurried out to stop himself from throwing up. For a long time after, his eyes burnt with the apocalyptic scene.

Roland wept softly, fists clenched, his forehead pressed up against the window.

‘They delivered the frame for the swing this morning. If you only knew how many times I’ve dreamt of the kids playing on the swing. Their laughter … Why didn’t she tell me sooner that she didn’t like chickens?’

The Loiret can be pretty in the spring. The tubular structure of the swing frame stood stiffly between two clumps of hydrangeas. Gabriel had cooked a comforting blanquette de veau for Roland. But his friend had barely touched it. He had downed glass after glass, mumbling, ‘Why? Why?’ over and over again.

Two days later he heard that Roland had hanged himself from the swing frame.

Yes, there had been toys scattered there as well …

‘Do you want your meat back?’

‘Yes, please.’

‘Hold on, I’ll go and get it.’

Two large suitcases cluttered the lobby. Someone had either just arrived or was about to leave.

‘Here you are. What kind of meat is it?’

‘Shoulder of lamb.’

‘For a roast or stew?’

‘A roast – just with onions, garlic and thyme.’

‘That’s the way I like it as well. Are you doing the cooking?’

‘Yes, it’s something I enjoy. It’s for some friends.’

‘You’ll have to cook for me one day!’

‘Yes, why not?’

‘Okay then. Have a nice evening and make sure you take the door code this time. Dinners always go on till late.’

‘If you say so. Goodnight, Madeleine.’

‘What’s that?’

‘A shoulder of lamb.’

‘Why are you bringing me a shoulder of lamb?’

‘I was thinking of cooking it for the two of us, here, tonight.’

José’s eyes widened as he looked from the bloodstained parcel of meat to the unblinking expression of his customer standing at the bar.

‘That’s a strange idea.’

‘Is it? It’s just … As I passed the butcher’s this morning the meat looked good. But perhaps your wife’s back from hospital?’

‘No, a few more days yet.’

José seemed on edge. At the other end of the bar, two regulars had interrupted their dice game to watch them curiously.

‘Do you want something to drink?’

‘The usual please, a beer.’

José poured the beer then excused himself and went over to the two men by the till. They exchanged a few words in hushed voices. The men nodded their heads knowingly and resumed their game while José headed back to Gabriel, the tea towel slung over his shoulder.

‘All right then.’

‘Can you show me where the kitchen is?’

‘Follow me.’

It was small but well equipped and very clean.

‘The pots and pans are in this cupboard, the cutlery in this drawer.’

‘I’ll manage.’

‘I’ll leave you to it then.’

‘No problem. It’ll be ready in about half an hour. Would you prefer potatoes or beans?’

‘It’s up to you. Tell me, why are you doing this?’

‘I don’t know. It just seemed natural. You’re on your own, and so am I. You don’t mind, do you?’

‘Not at all. It’s just a bit unusual.’

The lamb had fulfilled its promise: juicy, cooked medium so it was still pink in the middle, with a crispy skin. All that was left on their plates at the end were the bits of string. The deliciously tender potato gratin had also been polished off. As he had carried the steaming, sizzling dish through from the kitchen, Gabriel had seen José sitting awkwardly at the table like an uncomfortable house guest, staring at his own puzzled reflection in the black screen of the television which he had not dared to turn on.

‘Relax, make yourself at home,’ Gabriel had wanted to say.

They had wolfed down their food, their grunts of satisfaction punctuated by timid smiles.

When he was full, José had leant back in his chair, his cheeks flushed.

‘Now that was quite something. Bravo! You’ll have to give me the recipe for Marie.’

‘It’s not difficult; the key thing is the quality of the ingredients.’

‘Even so … Are you a chef?’

‘No, but I like cooking from time to time. I enjoy it.’

‘You’ve got a talent for it. Do you like port, by the way? I’ve got some vintage, the real thing. My brother-in-law sent it to me from back home. You can’t buy anything like it here. They make all kinds of rubbish out of cider or chouchen. Tell me what you think of this.’

The toys had gone. He had not noticed before. He felt lost all of a sudden, somehow disappointed that the scattered toys were no longer there and the television silent. He felt as though he had narrowly missed something. A train perhaps? His heart was hammering in his chest as though he had been running.

‘Here you go, try this!’

José poured the syrupy ruby liquid into two small glasses. It looked like blood. From the first mouthful, Gabriel felt his insides become coated in crimson velvet.

‘What do you say to a bit of fado? Have you heard any Amália Rodrigues?’

‘I’m not sure.’

‘She’s divine! Hold on …’

José leapt up and waddled bow-leggedly into the living room. A cassette player clicked into action and the heartrending sound of a voice dripping with tears rose through the gloom.

‘It’s wonderful, isn’t it? I think it’s the most beautiful sound in the world. Do you ever get homesick?’

‘I don’t know. I suppose so.’

‘Where are you actually from?’

‘I move around.’

‘But you must have been born somewhere.’

‘Naturally.’

Not getting anywhere, José poured himself another drink.

‘It’s none of my business really. I’m only asking because those are the kind of questions you ask when you’re getting to know somebody.’

‘True enough. What’s she singing about?’

‘The usual stuff: broken hearts, one person leaving, the other left behind. You know, life.’

‘Do you miss your wife?’

‘Yes. It’s the first time we’ve been apart since we were married. I find it hard to sleep on my own. I couldn’t last night. I cleaned the house from top to bottom, as if I was looking for her underneath the furniture. Stupid, isn’t it?’

‘No, not at all.’

‘I went to see her this morning at the hospital, but she was asleep. The doctors told me the operation went well.’

‘That’s good.’

‘Yes, only another two or three days to go. It was raining this morning. It always rains here, for days and weeks at a time.’

Amália Rodrigues fell silent and, as if to confirm what José was saying, they heard raindrops pattering on the zinc roof over the courtyard at the back.

‘Have you ever thought about moving back to Portugal?’

‘Yes, but Marie’s a Breton. To her, Portugal is a place you go on holiday. Nothing more.’

‘And what about you, here in Brittany? Is it a holiday?’

‘No, it’s for life. The kids were born here. You know how it is.’

A car passed by in the street, like a wave sweeping through the silence.

‘You’re not drinking?’

‘No, thank you, I’m fine. Anyway, I’d better be off.’

‘It’s not that late …’

‘I get up early.’

‘Ah, well. It’s been good fun. Are you coming back tomorrow?’

‘I think so.’

‘I told my friends earlier, the ones playing dice, that you were one of Marie’s cousins. It would have been complicated to explain.’

‘Good idea.’

‘So I’ll see you tomorrow. And I’ll cook!’

It was a cave, a modern-day gloomy concrete cave at the back of an underground car park. Many had lived there, some still did, leaving evidence of their squalid existence painted on the walls: smears of shit, obscene graffiti, markings daubed in wine, piss and vomit. Burst mattresses and soiled blankets were piled up like animal skins in a rotting heap, teeming with so many lice, crab lice and fleas that they appeared to be coming to life. The place stank, though it was worse outside, except that it was so cold there you didn’t notice it. Simon’s squatting silhouette stood out from the shadows like a figure in a Flemish painting. In front of him, meths fumes rose from an empty pea tin which was precariously balanced on a small gas stove. Wearing frayed mittens, he held the stove steady with one hand; with the other, he dangled a chicken over the flames by its neck.

‘Couldn’t the old bitch have given you a cooked one?’

‘She was on her way out of the supermarket. She’d got two for one. It was still kind of her.’

‘The road to hell is paved with good intentions. Do they think we’ve got all mod cons here? Pass me the wine.’

Beneath the scarf wrapped round his head, Simon’s swollen eye was watering. He raised the bottle to his cracked lips and toothless mouth and took a long swig while keeping his eyes on the chicken that had started to char over the flames.

‘It’s burning.’

‘Only the skin. We’ll scrape it off. I’ll turn it over.’

Simon grabbed the chicken by its feet and flipped it over, causing its comb to catch alight. He quickly blew it out.

‘“Et la tête, et la tête, alouette, alouette …” Light me a ciggy, will you? This is going to take for ever.’

Gabriel lit a crooked Gitane and passed it over. He was starting to warm up, more because of the fire’s glow than its heat. He took off his leaking trainers and rubbed his feet. He had lost nearly all feeling in them from all the walking he was doing. When there is nowhere to go you spend a lot of time on your feet. He swigged the wine and from beneath his layers of worn clothes he pulled out the crumpled pages of a newspaper that had been wrapped around his chest.

‘What’s the news?’

‘They’re going to ban cigarette smoking in public places.’

‘Must have been a cigar smoker who dreamt that one up!’

You could never tell if Simon was crying or laughing. Either way, a dry cough shook him like a half-empty bag.

‘Oh, it’s all for our own good, isn’t it? Talk about a bloody nanny state! No smoking, no drinking, no fat, no sugar, no sex. It’s as if they don’t want us to die. How nice of them! What else does it say?’

‘An inventor has just come up with an indestructible fabric. It’s cold- and heat-resistant and even bulletproof. The Vatican has ordered some for the Pope.’

‘Gone off the idea of heaven, has he? He’s only trying to save his own skin, like any old moron. Here, can you hold the chicken a second? My hands are full.’

The bird was now black at either end. The skin was peeling off like flecks of paint from the lead pipes in the squat they had been thrown out of three days earlier.

‘Apparently lead isn’t too good for you either.’

‘I know! I once saw a guy riddled with it in Marseille. It took five men to carry him!’

A fresh coughing fit made Simon double over. But this time he was laughing at his joke about the lead.

‘Life’s a killer. Especially for the poor. To live a long and healthy life you’ve got to live in a villa on the Riviera and be served by a white-gloved waiter. Yeah, but the sun gives you skin cancer! Turn it over or it won’t cook on that side. Shit, not like that! You’re going to fuck it up … Jesus, man, leave it, I’ll do it.’

The stuffy air was thick with smoke, and the smell of alcohol, charred meat and stale cigarettes. Both of them were hunched over, like monkeys in a cage. Everything was blurred, shapeless. The men weren’t men and the chicken wasn’t a chicken. Nothing but rough sketches gone wrong, crumpled into a ball and thrown into this stinking hole. Simon held the bird by its head and feet as if holding the handlebars of a motorbike heading straight into the wall.

‘Joan of Arc.’

‘What about her?’

‘She’s the only woman I’ve ever loved.’

‘What made you think of her? The chicken?’

‘Maybe. Or the Pope, I don’t know. I used to carry a picture of her around when I was a kid. I’d wank off over it in the toilets, looking at her in that tight, shiny armour with her tidy little page-boy haircut and her flag blowing in the wind. What I’d have given for a can-opener to get inside that …! Pass me the bottle and I’ll tell you.’

Simon finished off the bottle and started to sway to and fro with a fixed stare, his hands wrapped round his chicken handlebars, full speed ahead.

‘I once went to Rouen. Not Mecca or Lourdes like some people, but Rouen. I went and begged in the square where they burnt her at the stake. It was the most dough I’d ever made in my life – people were throwing their money at me! I got absolutely trashed that night – it was insane! Later on I was having a piss up against a wall when I saw her in front of me, stark naked, smiling at me with her arms and legs wide open. She said: “It’s about time, Simon!” and I screwed her. I screwed her like I’ve never screwed before. Up against the fucking wall. And you can believe it or not, but the wall started swelling as if I’d knocked it up, and just when I was about to shoot my load the wall fell in on me. But it didn’t hurt, not one bit. And behind the wall, behind the wall, there was—’

Gesticulating wildly as he relived the scene, Simon’s elbow smashed into the gas stove. The alcohol spilt over him and he was engulfed in flames like a living torch, while the chicken took the first flight of its short life and landed on Gabriel’s knees. Simon stood howling and banging his arms against his sides as if in the throes of a laughing fit. The fire took hold of him in a dazzling display of power, like a volcanic eruption. Gabriel froze, numbed by the wine, awestruck. Simon threw himself onto the pile of mattresses and covers and rolled about until he disappeared under a thick plume of smoke. Gabriel grabbed his bag, trainers and the chicken and ran as fast as he could. When he stopped to catch his breath by the banks of the Seine, he tore away at the half-cooked chicken and wondered what could have been behind that fucking wall.

Gabriel ripped shreds off the candyfloss and let them melt slowly in his mouth.

We should eat nothing but clouds, he thought.

In front of him a merry-go-round whirled round: as it sped up an elephant, a fire engine, a white swan and a motorbike all dissolved into a kaleidoscope of colour and bright lights, punctuated by the piercing shrieks of the children above the heady music of the barrel organ. He had never seen Simon again. Had he melted away as well? He had almost forgotten what had happened in that underground car park it was so long ago. He remembered the chicken, the taste of charcoal and raw meat. His fingers felt sticky. He didn’t have a handkerchief so he wiped them on the underside of the bench. The smell of chip fat and hot sugar hung in the air. Even the rain was sweet. Nobody seemed to realise. People came and went as if the sun were out, as if they were happy. As if. It was a tiny funfair with just a merry-go-round, a tombola, a shooting gallery and a sweet stall. He had stumbled upon it after crossing the bridge that straddled the river. This was the furthest he had been in the town and he felt as though he had crossed into another town entirely. When on foot you always travel further than you expect. You only realise how far you have gone when it’s time to go back. Because you always have to go back.

‘Romain, sit up straight! And hold on!’

The small boy wasn’t listening to his mother. Not any more. He was laughing, on the brink of hysteria, and bouncing up and down on his elephant, which was charging furiously forward, driven by its own massive weight. It trampled everything in its path: the fire engine, the white swan, the screeching mother with her hands cupped around her mouth, the town hall, the post office, the station, the whole town. Its dreary revolving existence had driven the elephant mad. The child and the elephant were one, a single ball of pure energy, out of control, hurtling through space, destroying everything in their path without remorse. They knew that this moment of freedom would be brief and so they made the most of it. Nothing could stop them while they were in orbit. It was at moments like this that you could kill somebody. You could kill somebody over nothing at all, because nothing was stopping you and you were too high to think about humanity.

The merry-go-round slowed to a stop. It was over quickly. Gabriel stood up as he had got up from the bench at the station a few days earlier, with sticky hands.

‘Five shots, five balloons, the prize is yours.’

The butt of the rifle was as cool and soft as Joan of Arc’s skin. It was easy; all you had to do was empty your mind. Kept aloft by an electric fan, the five dancing coloured balloons exploded one by one. Load, aim, fire … load, aim, fire. It was all over in less than three minutes.

‘Well done. You’re a fine shot, sir!’

The stall holder resembled a badly restored china doll with her cracked make-up, bottle-blonde hair with dark roots, and thick red lipstick that had smeared onto her false teeth. Her glazed eyes, which had seen too much, were as lifeless as those of the hideous toy panda which she placed on the counter.

‘Your prize!’

At the sight of the black and white animal with its outstretched arms and beaming smile, Gabriel took a step back.

‘No, no thank you. It’s fine.’

‘Go on! You’ve won it, you have to take it.’

‘No, I …’

‘When you win something, it’s yours. Give it to your children.’

‘I don’t have any.’

‘Well, you’d better get busy! Take it, go on. What am I supposed to do with it? I’m no thief. C’mon now, stop making a fuss.’

‘Well, okay then. Thank you.’

It wasn’t that it was heavy – it was just difficult to carry. He didn’t know how to hold it. By the ear? By the paw? Or by wrapping his arms round the whole thing? As he walked past, people turned to stare, some smiling and others laughing outright. The cuddly toy didn’t care. It continued to gaze wide-eyed at its surroundings with the same fixed happy smile, regardless of which way up it was carried. And so Gabriel arrived at the Faro encumbered by his unwanted progeny. The metal shutter was pulled down, but he could see a light on inside. He knocked several times, the panda perched on his shoulders. Finally José appeared, unsteady on his feet and looking anxious.

‘Oh, it’s you. I forgot, I’m sorry. In you come.’

The shutter rolled up slowly with the grating sound of rusty metal. It ground to a halt halfway up, exhausted, and Gabriel had to squeeze underneath. José looked as worn-out as Gabriel.

‘Is everything okay, José?’

‘Not really. What’s that?’

‘A panda. I won it at a shooting gallery. I thought the kids might like it.’

‘That’s kind of you. Come on in.’

On the table in the back room the bottle of port stood next to an empty glass. Gabriel tossed the grinning panda onto a chair as José slumped on another. Though one was in a state of bliss and the other in despair, Gabriel couldn’t help but notice a resemblance between the two of them. He sat down and waited silently while José covered his face with his hands, rubbing his eyes and stubbly cheeks.

‘Do you want a drink? Shit, it’s empty. I’ll get another.’

José didn’t move though. It was as if he was stuck to his chair, which was in turn welded to the floor. The room was silent except for José’s laboured nasal breathing, drawn up from the depths of his chest. Beside him, the panda, like a happy guest, sat waiting for dinner. The only thing it lacked was a napkin round its neck and a knife and fork in either paw. It was exactly the same size as José.

‘How’s Marie?’

‘Well, you know … It’s not a cyst. They don’t know what it is. She was sleeping. I mean … she’s in a coma. She looks so different, all yellow, her nose all pinched, and purple around her eyes. She’s got no mouth, just a small slit with a tube coming out. And all the machines in her room make noises like televisions that haven’t been tuned properly. They either don’t know what’s wrong with her or they just won’t tell me. I didn’t recognise her at first. I thought I’d got the wrong room.’

His eyes filled with tears and his nose began to run. He was drowning from the inside. Gabriel lowered his head and traced the outline of a daisy on the tablecloth with his finger. She loves me, she loves me not …

‘Have you eaten?’ Gabriel asked.

‘No, I’m sorry, I completely forgot about you.’

‘Don’t worry. You need to eat something though.’

‘I’m not hungry.’

‘I could rustle something up. I know where everything is. Let me help.’

‘If you want. Thank you for coming. I don’t really know what I’m doing at the moment. There are some bottles under the sink. Let’s have a drink.’

‘I’ll go and get you one.’

Pasta, tomatoes, tuna, onions and olives. Gabriel worked like a surgeon, his actions neat and precise. It was like being back at the shooting gallery. No need to think, just act. In the space of fifteen minutes the pasta bake was in the oven, he had laid the table and filled the glasses with wine. José had already emptied his twice and was staring mournfully at the panda.

‘What kind of animal is it? A bear?’

‘A panda.’

‘It’s big.’

‘Yes.’

‘The children love anything that’s big. It reassures them. I didn’t have the heart to go and see them after the hospital. I phoned them and said that everything was okay and that the four of us would be together again soon.’

‘You did the right thing.’

‘They didn’t believe me. “Papa, your voice is all funny,” they said. You can’t hide anything from kids. They’re cleverer than us. When I was a kid, I knew everything, well, most things. But now I don’t understand a thing. What’s the point of growing up? It’s stupid.’

‘I’ll get the pasta.’

With his elbows on the table, José hoovered up his meal. The tomato sauce ran from the corners of his mouth, to his chin and down his neck. Like an ogre. Once finished, he pushed the empty plate away and burped, then wiped his mouth on his cuff.

‘Jesus, that was good! You’re hired. I’m not kidding. You’re hired, seeing as Marie …’

José thumped the table. The bottle and glasses went flying. The panda slumped on its shoulder. José grabbed the stuffed animal and threw his head back. All you could see was his uvula going up and down like a yo-yo.

‘For God’s sake, why!?’

He pounded the tablecloth with his fists. The panda rolled onto the floor. José collapsed forward, his forehead on the table, his arms dangling by his sides. His back began to shudder. Gabriel picked up the bottle and glasses.

‘We had everything we needed to be happy. Everything.’

‘I know.’

José looked up and wiped his nose on his sleeve. He was frowning, his mouth twisted in an ugly grimace.

‘What do you know?’

‘Pain.’

José screwed one eye shut and focused the other on Gabriel. He was dribbling. He was ugly. He was hurting.

‘Who are you? I don’t give a shit about your pain. Why aren’t you telling me she’s going to be okay, that everything is going to be fine, like it was before? Why are you looking at me with those doe eyes and not saying anything?’

‘Because I don’t know.’

‘You don’t know?’

Furious, José leapt up, his eyes bloodshot, and knocked the table over. The veins in his neck bulged, his muscles tensed. He stood there, shoulders hunched and fists clenched, ready to pounce. Gabriel didn’t flinch.

‘You don’t know anything. You don’t know anything at all! All you know is how to cook. Get lost. Fuck off. You and your fucking bear. Beat it. I never want to see you here again. Never, ever!’

The pavement gleamed as if covered with shiny sealskin. The night skies of cities are always yellow, rain or no rain. Gabriel picked up the panda and laid it on the lid of a dustbin. It sat there, confident, radiant, offering its open arms to whoever wanted to take it home.

‘When they die, cats purr. Yes, it’s true, I’m telling you! When I had to have mine put down she was purring … Hang on a second … Monsieur Gabriel, can I talk to you a moment?’

‘Of course.’

Madeleine said her goodbyes to the Sonia on the other end of the phone and hung up. She was wearing a low-cut pink T-shirt, which emphasised her chest, especially when she leant forward. Her little nameplate necklace bounced from one breast to the other.

‘Are you thinking of staying for much longer?’

‘I don’t know, perhaps a bit longer, yes.’

‘It’s just that your room is reserved for someone else from the fourth to the seventh. Would you mind changing rooms?’

‘No, not at all. What day is it today?’

‘Actually, it’s the fourth.’

‘Ah, well, in that case I’ll go and get my things.’

‘Thank you. The rooms are practically the same, you know.’

‘It’s no problem at all.’

‘I’m putting you in number 22. It’s on the next floor up.’

‘Great. I’ll go and get my bag.’

‘One more thing. I wanted to ask you what you were doing today.’

‘Nothing really. Why?’

‘I’m off this afternoon and I wondered, well, whether you fancied going for a walk? It’s not raining.’

Her cheeks flushed red. She should blush more often. It suited her.

‘Is that too forward?’

‘No, not at all. It’s a great idea. Of course, I’d be glad to.’

‘I finish at noon.’

‘Perfect. I’ll see you later then.’

It was the first time he had seen her outside work, in her entirety, standing up and not behind the desk. She was tall, as tall as he was, maybe even taller. It was a little intimidating. Even so, it was she who lowered her eyes and clutched her bag with the awkward charm of a young girl caught stepping out of the bath.

‘Okay, shall we go?’

‘After you.’

She opened the door as if about to plunge into the unknown and strode off down the road on her long legs in a sort of blind charge, the tail of her raincoat flapping in the wind. She talked as fast as she walked.

‘I know a great Vietnamese restaurant, or Italian if you prefer. There’s a very interesting models museum and a cinema, but I don’t know what’s on. It’s a small town. There’s not a lot to do, but it is pretty, especially by the banks of the—’

‘I’ve got some calves’ liver.’

‘Sorry?’ Madeleine stopped in her tracks. Her dark eyebrows arched so high they almost touched the roots of her hair.

‘Calves’ liver. I could cook it for you if you want. I have all the ingredients. Do you like calves’ liver?’

‘Yes, yes, I love it, but—’

‘At your place. I could cook it there.’

Madeleine looked bewildered, as if she’d been plonked down in the middle of nowhere at a crossroads of identical streets. She burst out laughing.

‘You’re quite something, aren’t you! Why not? I live nearby.’

They walked side by side at a slower pace. Madeleine didn’t say a word, but shot Gabriel the occasional curious glance, followed by a disbelieving shake of her head.

‘You know,’ Gabriel said, ‘I often end up wandering around unfamiliar towns. I like it, but it’s nice to have somewhere to go.’

‘Do you travel around because of your work?’

‘It’s not exactly work – it’s a service I provide.’

‘What sort of service?’

‘It depends.’

‘And does it take you all over?’

‘Yes, all over.’

‘Here we are. I live on the third floor. The one with the geranium at the window.’

The stairwell was unremarkable. It was typical of a modest 1960s building, clean, with a succession of dark-red doors distinguished from one another by nameplates and colourful doormats. Madeleine Chotard’s – that’s what was written on the copper nameplate: M. Chotard – was in the shape of a curled-up cat.

Cats were everywhere in the two-bed flat in all sorts of varied guises: a lamp stand, wallpaper, cushions. There were figurines in wood, bronze and porcelain of cats jumping, sleeping, arching their backs, stretching …

‘The kitchen is on your left if you want to put your stuff down.’

Even more cats in the kitchen: cat salt and pepper mills, cat jugs … Gabriel put the food on the worktop next to the hob and went back into the living room to join Madeleine. The room was small, but bright and very clean. Not a single cat’s hair in sight.

‘Make yourself at home. Do you want a drink before you start?’

‘I’d love one.’

Being at home obviously freed Madeleine from the demeanour required at work. She was comfortable with her body, most probably sporty, natural – what’s known as a fine specimen. The strip of flesh visible between the bottom of her T-shirt and the belt of her skirt when she bent over to take a bottle from the cupboard was smooth and flat, not an ounce of fat.

‘I haven’t got a great choice. To be honest, I hardly ever drink aperitifs – I just keep some for friends. Do you fancy a Martini?’

‘Perfect!’

It was as if there were a second world underneath the smoked glass of the low coffee table, an almost aquatic parallel universe where the reflection of the hands dipping into the bowl of peanuts merged with the floral carpet.

‘It’s funny seeing you here,’ she said.

‘It was you who invited me, the other day. You suggested I cook for you.’

‘I was joking.’

‘Well, I took it seriously. Would you rather go to a restaurant?’

‘No! It’s just that it’s surprising, that’s all. Normally you get to know people in a public place like a café or a club …’

‘A neutral place, yes. But why do you want to get to know me?’

‘I don’t know. Maybe because you always look a bit sad and bored.’

‘You must get a lot of people like that at the hotel, travelling salesmen, loners, people passing through …’

‘This is the first time! Don’t think—’

‘I didn’t mean anything like that, believe me. I’m happy to be here. Are you hungry?’

‘A little, yes.’

‘Okay then, I’ll get started.’

‘Do you want me to show you …?’

‘No, it’s fine, thanks. I’ll manage.’

It was as he had expected. Luckily, he’d thought of everything. It was a typical singleton’s kitchen. The fridge was practically bare and contained just a few fat-free yogurts, half an apple wrapped in cling film, some leftover rice, a half-frozen lettuce stuck to the back of the vegetable drawer and a jar of Nutella for those nights when she needed comfort. It was touching.

The new potatoes were soon bobbing up and down in the boiling water, the shallots slowly caramelising in the pan to which he added the two good-sized pieces of calves’ liver drizzling them with balsamic vinegar and sprinkling a pinch of finely chopped parsley. The surrounding white ceramic tiles, unused to such aromas, blushed with pleasure. Madeleine’s face appeared in the doorway, her nostrils twitching.

‘Mmm, it smells nice.’

‘You can sit down if you like. It’s almost ready.’

The liver was cooked to perfection, the onions melted in the mouth and the potatoes, glistening with butter, were as soft as a spring morning.

‘It’s been a very long time since I’ve had calves’ liver. I never think to buy it. It’s delicious. And the shallots …!’

I am cooking for you because I like you. I am going to feed you. We barely know each other and yet here we are, just inches apart, where together we’re going to drool over, chew and swallow the meat, vegetables and bread. Our bodies are going to share the same pleasures. The same blood will flow in our veins. Your tongue will be my tongue; your belly, my belly. It’s an ancient, universal, unchanging ritu al.

‘… and that’s why she was worried.’

‘Who was?’

‘My grandmother, of course.’

‘Ah, yes, sorry.’

‘It was just a bit of anaemia. It often happens to kids who grow too quickly. I hated that.’

‘What?’

‘Minced horse meat cooked in stock. I just told you. Weren’t you listening?’

‘Yes, yes, of course. Minced horse meat cooked in stock. It’s true. It can’t have been that appetising for a little girl.’

‘You said it. But she thought she was doing the right thing. I was very fond of her. I’ll have a bit more wine, please. Thanks, that’s enough! I think I’m a little bit tipsy.’

‘Did she die?’

‘Yes, five years ago.’

‘And your cat as well?’

‘Yes. How did you know?’

‘I accidentally overheard you mention it on the phone this morning.’

‘It’s true. Last year. She was called Mitsouko, after my perfume. She lived to be fourteen.’

‘And you haven’t replaced her?’

‘No, but I often think about it.’

‘When you have your Nutella nights?’

‘Nutella nights? What do you mean?’

‘Nothing. I don’t know why I said that.’

‘Would you like coffee?’

‘Yes, please.’

The flat had already changed. It was now filled with the smell of cooking, rather than the smell of nothing at all. Things had been moved around and the sofa cushions were creased. There was another person there. Madeleine must have been aware of it when she heard him moving around in the kitchen. Gabriel walked over to the window and raised the net curtain. It was a small, anonymous street, the sort of street you go down on the way to somewhere else. How many times had Madeleine stood by the window cuddling her cat, waiting for something to happen down below? And how many times had she drawn the curtains without witnessing anything but the slow flowering of her picture-postcard red geranium?

‘Sugar?’

‘No, thanks.’

‘The street isn’t exactly lively, is it?’

‘It’s a street.’

‘I sometimes think it’s more of a dead end. The rent is cheap, though, and it’s quiet.’

‘I once lived on a street like this. One day I saw a Chinese man fall from a sixth-floor window.’

‘That’s awful!’

‘It took me a moment to realise that it was the Chinese man from the sixth floor. He flashed past. It was a beautiful day; the window was open. I didn’t see what happened, but I felt it, like a large bird or a shadow passing over. And then I heard shouts. I leant out of the window to have a look and saw something lying in the middle of the road in the shape of a swastika. There was an elderly couple across the street. The woman was screaming. All the other windows opened at once. Someone yelled, “It’s the Chinese man from the sixth floor!”’

‘What did you do?’

‘I think I closed the window. I didn’t know him that well. We’d met a few times on the stairs. A neighbour told me later that he was a bit unstable and part of a cult, something like that.’

‘It must have been a weird feeling.’

‘You feel a bit of a voyeur, even if it’s unintentional. All day it felt as though I had something in my eye I couldn’t get out, a kind of indelible subliminal image. It was quite annoying. I don’t know why I’m telling you this – it’s stupid.’

Gabriel regretted telling the story. The room now teemed with falling Chinese men. Madeleine was hunched over, staring into her cup, her brow furrowed. Would she ever dare open her window again? Would she let her geranium die of thirst? What if she was indeed sporty and her hobby was parachuting? He was an idiot.