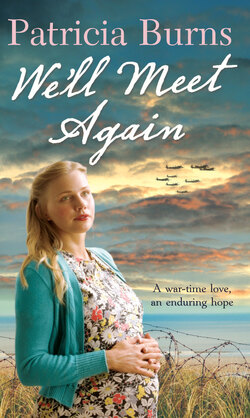

Читать книгу We'll Meet Again - Patricia Burns - Страница 10

CHAPTER FIVE

ОглавлениеTHE storm had been brewing all day. Annie could feel it in the viciousness of her father’s criticisms. He always picked holes in everything she did, but on some days it was different. Instead of it being just the way he was, there was an added force behind his words, winding tighter and tighter until the inevitable explosion. The best thing to do was to keep out of his way, but it wasn’t always possible. When the mood was upon him, he seemed to seek difficult jobs that needed both of them to complete so that he could feed his anger at the world and at her. Today it was replacing some fencing. Annie had to hold the posts while Walter hammered them into ground hardened by the summer sun. As they started on their task, planes droned across the sky—a formation of bombers. To the south, ack-ack fire started.

‘It’s them, the Jerries,’ Annie said, gazing up and seawards at the dark shapes. Puffs of smoke were breaking around them, but they flew on unharmed. ‘Where are our boys?’

Her father took no notice.

‘Hold it still, yer useless bitch,’ he growled. ‘How can I hit it if yer waving it about like that?’

Head averted, eyes screwed shut, Annie held the post at arm’s length as Walter smashed down with the sledgehammer.

From the west she heard a higher-pitched engine noise. With an accelerating roar, fighters swooped overhead. Annie squinted skyward. Spitfires! Her hands shook as she held the fence post.

‘For Christ’s sake, you stupid mare—’

Her head stung as her father caught her a blow with the back of his hand. She looked at the post. Straight, she had to hold it straight.

Gunfire cracked over the sea. The engines whined and roared and droned. Caught between fear of her father and of the approaching planes, Annie hung on to the post for all she was worth. Walter swung the sledgehammer. Each blow drove the stake a fraction of an inch deeper into the unyielding soil. The vibration kicked up her arms and felt as if it were shaking her brain inside her skull. Half a mile away over the sea, there was an explosion. Annie looked up. A bomber was going down in flames.

‘They’ve got one!’ she cried.

At that moment the sledgehammer descended again, out of true. The post split at the top.

Walter’s hand cracked into her.

‘I told you!’

‘Sorry,’ Annie gasped.

The life-or-death struggle continued in the air, the planes passing over the coast not half a mile to the south of them, but Annie dared not look up from her task. Her father was nearer than the invaders, and she feared him more.

Each fence post seemed to take an age; none of them went in entirely straight and it was all her fault.

As always, her mother had the meal ready dead on midday. Not even the possibility of a German plane landing on the farm would stop Edna from having dinner ready the moment Walter wanted it.

‘Did you see—?’ she started as Walter and Annie came through the back door.

Then she saw their faces, sensed the atmosphere and lapsed into silence. Her hand shook a little as she ladled out the stew and handed it round. Annie noticed that, as usual, most of the meagre portion of meat was on her father’s plate, while she and Edna had vegetables and gravy. It didn’t even occur to her to question this. Appeasing her father was the number-one priority.

Both women ate silently, covertly watching Walter. Faintly through the window came the sound of another dogfight somewhere in the summer sky.

Walter threw his knife and fork down. ‘What d’you call this, then?’ he demanded.

Annie held her breath. This was it. Fear throbbed through her.

‘B-beef and vegetable stew,’ Edna muttered, keeping her eyes on her own plate.

‘Beef? There’s no beef in this. It’s nothing but carrot and swede. Swede! Flaming cattle food!’

Edna said nothing. Long experience had taught her that anything she said would be fuel to the fire.

Walter’s hand slammed down on the table. ‘Where’s the meat in it?’ he demanded.

The silence stretched, marked out by the ticking of the clock on the mantelpiece.

‘Well?’ Walter barked.

‘It—it’s the rationing,’ Edna whispered.

‘The what? What did you say, woman?’

Edna’s lips trembled. Annie felt sick. She longed to intervene, but knew that it would only make things worse.

‘Rationing,’ Edna repeated, her voice barely audible. ‘I got to m-make it stretch.’

‘Rationing? Flaming government! Here I am, working my fingers to the bone producing beef and those flaming pen-pushers up in Whitehall think they can tell me how much of it I can eat? I’ll give them rationing—’

Relief washed over Annie, leaving her limp and wrung out. It was all right. Her father’s rage had been diverted. She and her mother sat silent, not even meeting each other’s eyes. They ate, though neither of them had much of an appetite left, but the food must not be wasted, so they pushed it into their mouths, chewed, swallowed. All the while Walter’s invective flowed round them, battering their ears, hurting their brains, and they were glad, for words directed at a distant authority were nothing compared to blows rained on them.

When the meal was over, Edna immediately started washing up, busying herself to deflect any possible criticism. Annie was left to follow her father out into the fields again.

As they trudged back to the half-finished fence, she looked towards Silver Sands. There it was, crouching under the sea wall. And there he must be. Tom. Tom, from a magic land called Norseley, far away from Wittlesham, where all families were happy and no one got hurt. In her daydreams now, she no longer got whisked over the rainbow to Oz, but ran away with Tom, hand in hand, to Norseley.

The afternoon went on for ever. To the north and to the south of them, distant gunfire could be heard, while white vapour trails and black balls of smoke scrawled across the sky. At first Walter worked silently, but as the sun beat down on their heads and the grinding labour began to sap his strength, the curses and the criticisms started again. The rant against the government had not been enough of a safety valve. Life itself was stacked against Walter, and someone had to take the blame.

‘Look at that—that’s not straight. For Christ’s sake, can’t you do anything right? All you got to do is hold it straight while I hit it. It’s not difficult. A halfwit could do it. Jesus wept! Why are you so useless? Why was I given just one useless girl—?’

And so on until he was ready to hammer in the next stake, mercifully leaving him without spare breath for speech.

Annie held grimly on to each fence post, trying her hardest to hold it still, hold it straight. But she could not fight against the force of the hammer blows when they landed off-centre and drove the post out of true. Her head ached from the sun and her body ached from bracing against the sledgehammer. She tried to cut her father out, centring her thoughts on the evening to come. She would walk across this very field, past Silver Sands, over the sea wall, and there Tom would be, waiting for her. And then everything would be all right.

When the posts were at last driven in, then the barbed wire had to be stretched between them and held with heavy-duty staples. Annie struggled with the coil while her father hammered in the staples.

‘Keep it tight, can’t you? No good having it sag like that. Beasts’ll be through that before the week’s out. Tighter, you stupid mare! Put some effort into it. Jesus—!’

At last the job was done. Now there was only afternoon milking to get through. It was like walking on the edge of a volcano. Annie knew it would only take one mistake to set off the eruption. Weariness and tension made her clumsy. Only luck brought her through without making a serious blunder.

Teatime was another tense meal, the silence broken only by the Home Service. They all put their food down and stopped chewing to listen to the six o’clock news. Forty-two Allied planes had been lost, but they had claimed ninety of the enemy. In homes across the country there were desperate cheers for another day’s holding on. At Marsh Edge Farm Walter merely grunted, while Annie and Edna said nothing.

Annie thought about the plane she had seen go down. One fewer to invade England. Later, she would talk to Tom about it, for he must have seen it too.

Annie ached to get away. Soon, soon the chores would be over and she would be free. Every fibre of her being longed to escape, to set off across the fields to the sea wall. But her conscience fought against it. What about her mother? Without her there, her mother would be sure to catch it. She was in a ferment of indecision.

They finished off the last tasks of the day and went back into the house. Walter dropped down into his chair.

‘Pull my boots off, woman,’ he growled.

Edna hurried to do as she was bid, kneeling on the rag rug in front of him. She fumbled the laces undone, then began to draw off the boot. It stuck. Edna tugged and caught Walter’s bad toe.

‘Aagh! You stupid—’

He lashed out with his other foot. The heavy boot smashed into Edna’s shoulder, flinging her back so that her head cracked against the flagstone floor.

‘Mum!’

For a vital few seconds fear for her mother overcame fear for herself. Annie flew across the kitchen to cradle Edna’s head in her arms.

‘Leave her be, you interfering little bitch! Coming between man and wife—!’

Walter’s boot thudded into her legs and buttocks, while Annie and Edna clung together and whimpered with terror …

The mothers were talking on the veranda again—his mam, his aunty Betty and Mrs Sutton. This time, thank goodness, Beryl hadn’t come. The anticipation of seeing Annie filled Tom up, so that he felt as if he could almost burst with the excitement of it. There was so much to talk about, with the Battle of Britain happening right over their heads that very day. On top of that, he wanted to hold her hand again, and to walk along together with her as they discussed what had gone on in the sky. There wasn’t much time left now, just this evening and tomorrow, for on Saturday they had to go home. So every minute counted. He slipped out of the chalet, checked that his sister and the cousins weren’t looking, and made a run for the sea wall.

He was used to waiting. Sometimes Annie didn’t manage to get away till quite late. One evening, she hadn’t come at all. When he’d asked about it, she wouldn’t answer directly, wouldn’t even look at him, had just said she had to help her mother. Something about her expression had alarmed him. That look of fierce hatred that came into her face when her father was mentioned.

‘Why? What was so important that you couldn’t get away?’ he asked.

‘I just had to stay,’ she said.

‘But what for?’ he persisted.

‘I just had to, all right? Don’t you have to do things when your parents tell you?’

‘Yes,’ he admitted.

But he was sure there was more to it than that.

He slid down the wall and sat on the sand at the bottom. It was still warm from the day’s sunshine. He had given up all pretence of painting now and just lay against the rough grass, looking out across the water and thinking. Soon, Annie would be here.

The minutes ticked by and turned into a quarter of an hour, then half an hour. Annie did not come. Tom heard the mothers calling goodbye to Mrs Sutton. Another five minutes went by, and then someone came over the top of the wall. It was his sister Joan. Disappointment kicked him in the stomach.

‘Tom, Mam wants to see you.’

‘I can’t come now.’

‘You’ve got to.’

‘Tell her I’m busy.’

‘But you’re not. You’re not doing anything.’

‘Yes, I am.’

‘No, you’re not. You’re just sitting.’

‘I’m thinking. Now, go away.’

It took a bit more arguing, but in the end Joan went.

Where was Annie?

He didn’t allow himself to look at his watch. He sang Over The Rainbow to himself all the way through, twice. That was Annie’s favourite song. Still she hadn’t come. Bursting with impatience now, he climbed up to the top of the wall and looked out over the fields.

‘Tom!’

It was his mother, standing by the fence.

‘Hell’s bells,’ Tom muttered.

‘Tom, come down here, will you? There’s something I want to speak to you about.’

Reluctantly, he went.

‘Come and sit down here, dear.’

His mother was using her Very Reasonable voice. It was a sure sign of trouble. Silently, he sat down on the edge of the veranda with her. The children could be heard playing in the garden at the back. The other grown-ups were nowhere to be seen.

‘Now, dear,’ his mother began.

Tom looked at his watch.

Where was Annie? Was she coming across the fields this very minute?

‘You know I don’t like to interfere with your friendships—’

That wasn’t true for a start. She never had liked his pal Keith, because his dad was a collier. He made a non-committal noise.

‘But I have to say, I am a little bit concerned—’

Tom looked at her. What was she on about?

‘What?’ he said.

‘I’ve just had a little chat with Mrs Sutton,’ his mother went on. ‘Such a nice woman. Very genteel. And very well-meaning. She has got your best interests at heart, you know, Tom.’

‘Who—Mrs Sutton?’ Tom said, puzzled.

‘Yes, dear. That’s why she thought she ought to speak to me. You see—’ his mother hesitated, then went on ‘—you’ve been seen, dear, walking along the promenade. With a girl. Hand in hand.’

‘What?’

Outrage flared through him. How dared people spy on him and Annie? How dared they? He felt as if something precious had been ripped open and exposed to the world.

‘Who told her that? I know! It was that beastly Beryl, wasn’t it? Great fat lump. She’s got no right—’

‘So it’s true, then?’ his mother asked.

Tom wanted to hit himself for being so stupid.

‘Yes,’ he had to admit.

His mother put a hand on his knee. He jerked his leg away.

‘Well, dear, I have to say that I think you’re still far too young to be having girlfriends—’

‘She’s not a girlfriend—!’ Tom protested.

And then stopped short as he realised that maybe she was. What he felt about her was quite different from what he felt for anyone else, boy or girl.

‘All right,’ his mother conceded, though he could tell that she was just going along with him in order to gain a point. ‘So she’s just a friend. But you see, dear, this girl—she really isn’t a very suitable friend for you. Mrs Sutton knows her, you see, and she says she’s a very coarse, common girl. Not at all the sort of person that I or your father could approve of.’

Incensed, Tom jumped up.

‘Oh, really? Well, that’s just too bad, because I’m not asking you to approve of her. She’s my friend and you’re not stopping me from seeing her.’

He ran down the steps, ignoring his mother’s protests. How dared she say that about Annie? Annie was—

‘She’s not coarse and she’s not common,’ he shouted back at her.

‘Tom, dear—’

‘She’s better than Mrs Nosey Parker Sutton and Fat Beryl any day!’

‘Tom—’

He bolted round the side of the house, across the garden and out down the track, heading for Marsh Edge Farm. Anger propelled him across the fields, talking out loud to himself as his mother’s words revolved in his head. That interfering old bag, Mrs Sutton. He wanted to wipe her face in one of the cow-pats he was jumping over. And his mam believed her! She had no right. Nobody was going to stop him from seeing Annie if he wanted to.

It occurred to him that Annie had told him never to come to the farmhouse. But this was important. This was their last but one evening. They couldn’t waste it.

He slowed to a trot, and then a walk. The field he was walking across had a shiny new piece of barbed wire fencing down one side. That must be what Annie had been helping with today. He had seen two figures working while he’d watched the battle in the air. He opened a gate into the track leading up to the farmhouse and closed it carefully behind him. The edge of his anger had dulled now. He just wanted to see Annie.

And then there she was, coming out of the farmyard. Joy glowed inside him, lighting a great big smile on his face. He waved his arm above his head.

‘Annie!’

She came trotting down the track towards him. Tom broke into a run and, as they got nearer to each other, he noticed that Annie was limping. She stopped before they met. Her face looked different. Pinched. Distressed. Anxiety threaded through his delight. Something was wrong.

He came up to her and put his hand out to touch her arm. She flinched.

‘Annie—what is it? What’s the matter?’

‘What are you doing here? I told you not to come.’ Her voice was sharp, not like her ordinary voice at all.

‘You didn’t come,’ he explained. ‘I wanted to—’

‘You can’t stay here. He’ll see you, and then everything’ll be spoilt.’

‘Who?’ Tom asked. But, even as he said it, he knew. ‘Your father? Is it him? What’s happened?’

‘Just go! Now!’ Annie was frantic. ‘Please. I’ll come and see you tomorrow. I promise.’

And she turned and hurried away from him, still limping.

‘But, Annie—’

He took a few steps after her, his arm reaching out. Then he stopped. She was in deadly earnest. Whatever the trouble was, she thought his being there would make it worse. Slowly, reluctantly, he made his way back.

He got very little sleep that night.