Читать книгу All the Difference - Patricia Horvath - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеEarthbound

Sometime during the spring of sixth grade, the gym teacher sent me home with a note. She’d noticed how off-center I appeared when trying to touch my toes. Perhaps, she wrote, our pediatrician should take a look. A week or two later I stood in the doctor’s office in my underpants, bending over, raising my arms, shifting left and right, while he measured arms and legs, shoulders and hips. I leaned forward, arms dangling, knees straight. Touch your toes, he said. I couldn’t, the only kid in my class unable to do so, but so what? It wasn’t like I couldn’t read. Why, all of a sudden, should this require a doctor’s visit? I was bad at sports, that was all. Soon I’d put on my clothes, take a lollipop from the fishbowl on the receptionist’s desk, and go home. But the doctor asked me to sit down. He told my mother and me that I had scoliosis—a double, S-shaped curvature of the spine—and referred us to an orthopedic clinic at Bridgeport Hospital.

On our first visit to the clinic I sat in the waiting room, a long corridor with welded-together chairs that faced each other from opposite walls. Many of the patients were young girls like me. Some wore elaborate-looking back braces that made them sit up rigidly, their necks restrained behind stainless steel bars, their chins thrust forward onto plastic podiums. Several wore leg braces; one girl had a prosthetic leg that ended in a clunky brown shoe, like something an old man might wear. A few people seemed normal enough, though God only knew what they (or I) might look like coming out of the doctor’s office. For once not even a book could distract me.

I was not entirely certain what had landed me in this place. My spine was curved, that much I knew, my right side shorter, thwarted, out of all alignment. The word scoliosis meant little to me. I’d flunked a lot of fitness tests. I had a funny walk. Could they put you in the hospital for a funny walk?

There were many patients, one doctor; the wait, I discovered, could take all afternoon. When the nurse finally called my name, I trailed her and my mother into the examination room. My mother helped me tie the blue cotton gown in back. She looked me in the eye when the doctor would not and politely rephrased his third-person questions (“How does she sit?” “Honey, how do you sit?”) until he took the hint and asked me directly.

I lay on the examining table and the doctor measured my legs. I bent over while he took a protractor to my spine. I stood on one foot then the other. It was a game of Simon Says. The doctor muttered as he wrote things down. I was the body in the room, there yet invisible.

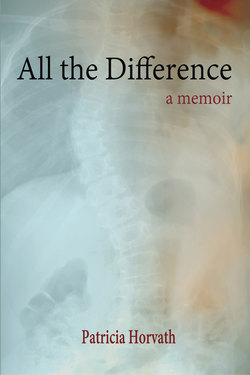

That day I was x-rayed for the first time and saw what a misshapen thing my spine was. It started out straight enough but about a third of the way down, my spine began a dramatic curve to the left, making an “S” shape as my lower vertebrae snaked back in the other direction before managing, somehow, to merge into my tilted pelvis. It was a wonder, I thought, that I could stand at all.

Dr. Mangieri explained that I had idiopathic scoliosis. I hated that word, idiopathic, the way it sounded like idiot, suggesting some causal link, some malfunction not only of body but of brain. Was this why I’d been lumped in with the slow girls in guidance? What did brains have to do anyway with a crooked spine? Later my mother explained to me that idiopathic meant the cause of my curvature was unknown. For scoliosis, this was common. Left untreated, the doctor continued, my condition could lead to progressive deformity, chronic pain, possible damage to pulmonary and cardiac function. My translation went something like: This is serious, pay attention, do what he says. And what he said was to exercise. Because I was still growing, he felt that a physical therapy regimen would strengthen my back muscles, helping them prod my spine in the right direction. If that didn’t work, I would have to wear a brace. And if that didn’t work . . . But on that first visit I don’t think he brought up surgery. What I remember is that the threat of the brace turned me into a physical therapy zealot, willing my muscles to straighten my recalcitrant spine. I would not become like those girls in the waiting room, a spectacle encased in plastic and steel.

To correct the half-inch imbalance in my leg length, I would have to wear a shoe with a built-in lift. The lift was expensive and the shoe had to be sturdy. In the dawning era of platform heels, I started junior high with two pair of orthopedic shoes—sensible brown oxfords and saddle shoes. They were heavy things, nothing like Hermes’s winged sandals. They made me feel earthbound, and I loathed them.