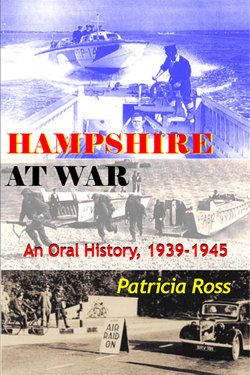

Читать книгу Hampshire at War - Patricia Ross - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE NAVY

Like the Army, the peacetime Navy had to make a rapid adjustment to the necessities of war, especially in view of early setbacks such as the loss of HMS Hood and HMS The Prince of Wales. Given the presence of Portsmouth and Southampton, the story of the Navy and the story of Hampshire between 1939 and 1945 are forever going to be intertwined.

A war-time love story: Mr Ronald Wilson of Upminster, born around 1925

Mr Ronald Wilson writes that his ‘Hampshire at War’ story is a love story. “I met my late wife Eileen when we were both at HMS Dragonfly, Hayling Island, in 1945. I was an ordinary AB [Able Seaman], having been medically graded Grade 5 and unfit for sea. Eileen was a Wren, stationed at the Suntrap Home building across the road. It had been a home for handicapped children.

“My wife was in Combined Operations from 1945 onwards. She worked on HMS Victory while back in barracks at Portsmouth. I had been on LCTs. In 1943, I was up in Scapa Flow on boom defence. We had anti-torpedo nets strung round the capital ships, and at each corner of the metal netting, which had a draught of 20 feet, was an LCT. I was on one of them.

Suntrap, Hayling Island: a contemportary postcard

“I came back to Southampton in 1943 to prepare for D-Day. Then in 1945 (I was 20) I had to go into hospital, the Royal Naval Hospital in Portland, with a serious ear complaint and was graded B5. I wanted to go back to sea - nobody likes being in barracks - but the doctor said that if I got ill again at sea and was away from medical attention, I may have died.

“So I went back to Portsmouth and met a friend who was a ship’s cobbler down at Plymouth. We had known each other when we were at school. And he said, ‘You can mend shoes.’ It’s true I have always been good with my hands. I applied to be a ship’s cobbler and it was granted. I did it and after a very short time I was sent to HMS Dragonfly on Hayling Island to be a ship’s cobbler. Part of HMS Dragonfly was where my Eileen was stationed. It was at the Suntrap Home.

“There was a fully equipped shoemaker’s shop - for the handicapped children, you know - and I started work. About the time the war ended, who should come in to have her shoes mended but Eileen! I looked at her and I fell in love.

“I had not had much contact with women. (I had been in action in the Navy. I had been bombed as a kid.) I couldn’t ask her to go out with me, I couldn’t find the words. But my mate got so fed up with my talking to him about this girl, he said, ‘If you don’t ask her out, I’ll ask her myself!’”

So Ron plucked up courage to ask and they went out together. But, he recalls, she said to him, “I’m sorry, Ron, I can’t feel the same about you as you feel about me.” He tried to forget her, then wrote a letter (a copy of which he showed to me) to say he was broken-hearted. So much so, he says, that when after this he used to play the piano at parties, he could not play sad love songs without weeping. He played for his brother’s wedding.

“Eileen and I didn’t see each other again until 1946,” he recalls. “She lived nearby at Hackney Wick, Plaistow, and her mother came to see my mother and said that she thought Eileen would like to see me again.” He says he was still heartbroken at 21 and he thought, “I can’t go through all that again.” So he told her mother that he would meet her outside West Ham United football club, but was purposely late. “I thought I’d give her every excuse to have second thoughts,” he adds. “But she waited.”

They were engaged a year later and married. “And we had such a wonderful life,” he recalls. “We had three children, two girls and a boy. We were not lucky, we were blessed! God blessed us. When she died I said, ‘I’ve never looked at another woman since I met you. I didn’t fancy anyone else.’”

When I first spoke to Ron in September 2002 it was eight months since Eileen died. “We stayed together, man and wife, friends, shipmates and most importantly we were lovers,” he said. “We spent 53 years and five months of wonderful life together up to the day she died, 28 January this year. She was 78.”

After he spoke to me, Ron was having a mass said for Eileen at the Hayling Island Roman Catholic church where she used to worship as a Wren all those years ago, he told me. It was a year since Eileen died and he misses her very much. When she was stationed at the Suntrap Home, her officer used to ask her if she was going to mass and if she said, ‘No, I’m on duty,’ the officer would tell her to go anyway.

Even in home waters, service in the Navy was subject to many dangers and pitfalls of war-time life. This is illustrated vividly by the experience of Phillip Bradley of Beaumaris, Isle of Anglesey

Phillip Bradley was a Petty Officer in the Royal Navy. He recalls an accident in about 1943, off Sandy Point. One of the LCMs was returning from firing practice back into Chichester Harbour and hit the sand-bar at low tide. In a strongish wind, the boat turned over. The lieutenant was thrown clear and swam ashore over to the Point. The COPP depot raised the alarm: both the mechanic and stoker were trapped inside the engine room. They banged on the hull to indicate they were alive, then both tried to swim out. There was a shield around the gun turret; the mechanic managed to get clear but the stoker was trapped under the shield and drowned.

However, not everything was doom and gloom. His unit got involved in the testing of some rather high-tech gear intended to be used in the event of a landing on hostile soil.

This group was from the main repair base at the yacht yard in Mill Rythe where the mechanics changed engines. Light relief was provided when LCMs broke their moorings once, during a gale and high tide, and had to be collected from Emsworth main street.

Phillip Bradley was involved in experimental trials with the Hedgehog. Spigots were fitted inside an LCA in four banks of six. Then fifteen-pound mortar bombs filled with sand were fitted over the spigots. He says that when boffins fired all 24 at once in Langstone Harbour, they split the bottom of the LCA and had to run to the beach - a near-disaster. Another test, on Wittering Beach, involved an LCA with a large tank inside filled with liquid explosive. On the rear end of the boat, on the stern deck, was a rocket-launching frame and a line, which was attached to the rocket and the fire hose, then the fire hose was blanked off at both ends and the explosive was pumped into the hose, with a fuse on. The LCA was backed off from the beach, the boffins fired the explosive electrically and the explosion blew a wide trench on the shingle. Phillip assumes this device was designed to clear a beach of mines.

Dunkirk, Pearl Harbour, D-day

Alfred Humphreys, born 1921, was a chief petty officer by the time he left the Royal Navy in 1959. He joined up in 1937. His early war service included sailing with Atlantic convoys.

“We went from Portsmouth to Dunkirk, in HMS Hebe, a minesweeper. Well, to Dover first. Dover then Dunkirk. We were originally sweeping the English Channel - magnetic mines - and we were badly damaged and had to go into Poplar docks, London, for a refit. When we went across to Dunkirk, we were damaged by shells and shrapnel. We were a fairly small boat, about 250 tons. We could get right up to the beach, for we only had eight-foot draught.

“When we got there, the men were swimming in the water and underneath the water. We took 450 back the first time. The second time, we had about the same, really. Another ship took Lord Gort back to Dunkirk to organise things, because we couldn’t. We were a target for the German planes. We shot down one.

“We had cargo nets. They [the soldiers] had to climb up onto the ship. We had to leave a lot in the water. It was a terrible sight. Heartbreaking. It makes me want to cry to talk about it. It’s a thing I try to forget, put behind me.

“We were so badly damaged, two tugs came down from London and towed us there. Thirteen or fourteen shell holes, one on the water-line. We had collision mats. We put them over the side and they clung. It let some water in, but not a lot.”

Leave was granted following Dunkirk: “I think each watch had six weeks’ leave during the refit. I came back to Portsmouth, drafted off the ship then. I was in barracks at HMS Victory, had six weeks’ leave and joined the Hunt class destroyer, HMS Lauderdale, and went out to the Far East. We went over to Sydney and I volunteered for the Australian navy.

“We were just going into Sydney when the Japanese done Pearl Harbour. It was a shock. I went off HMS Devonshire. We were taking supplies out to the troops, just coming into port when we heard about Pearl Harbour.”

Mr Derek Brightman, born 1925, of Cambridge, was second-in-command of an LCT on D-Day. He says he was trained at HMS Collingwood, Portsmouth, and volunteered for Combined Operations: “This meant my being trained as an officer on landing craft. I was posted to New Dock, Southampton, and joined LCT 809 and we were able to take nine tanks on board. We had two officers and eight to ten ratings. We practised for months on various beaches in the area, taking off tanks.”

The ever-present landing craft bridged the gap between the Army and the Navy’s expertise.

“We left New Dock, Southampton, on 4 June. You remember that D-Day was scheduled for 5th June but was postponed 24 hours? And we went to pick up our tanks. The banks were lined with people shouting and cheering. It was obvious they knew something was happening. We went to the Beaulieu River and took on our tanks and men of the, I think, 88th Battalion, Royal Engineers. They were all frightfully seasick and, you know, the first twelve hours of being seasick you think you are going to die! We set off into a rather violent sky, with massive lines of landing craft. We saw our battleships - HMS Rodney and HMS Nelson, I think - which had 16-inch guns, which are very large, and this was very comforting.

LCT854 (see p. 89)

“In a grey dawn, we arrived at the British Gold Beach. We had LCTs. Six went into the beach and unloaded their tanks. We went in the second six and unfortunately as we got near the beach we were hit by the mines of beach defences, and the door was blown up, onto my foot on board. It hurt. It hurt like hell.”

He explained that the first six of his flotilla’s LCTs had escaped snagging the beach defences because the tide was a little higher for them but had gone down slightly by the time he and the rest of his flotilla reached them in their other six craft.

“The thing I most remember about going onto the beach was the noise - particularly rockets from converted Tank Landing Craft [known as LCT(R)s] which they fired over our heads. We had not seen nor heard them before and did not recognise the noise.

“We were sinking fast and abandoned ship. It was so traumatic. I was only 19 at the time. I remembered being in the water, but that was the last thing I remembered for three weeks. The next thing I remember was being in a Survivors’ Camp at Lowestoft. I recall tiny little bits - little flashes of the Great Storm. I learned later that the tanks were recovered, when the tide went down, by our soldiers, so we did get our tanks there.

“We were lucky because out of our twelve ships, we lost only two. Our beach was not at all like the American one shown on the film Saving Private Ryan but the noise and confusion was the same. It was very realistic, the film, in that respect. I remember the excitement and the first six tanks coming back. And there we were!

“Earlier, at New Docks, we were living on the landing craft. There was a little ward room and mess and the crew lived on the mess deck. It was a Mark 4 LCT. They are quite roomy. There was a PO engineer and a cox. It was powered by two, about 500-horsepower, diesel engines. Our LCT course was to learn how to con it - basic navigation, berthing, turning. At Troon.

“On D-Day, on our new door we had Mulock ramps, orange, for the tanks to drop easily onto the beach. It was one of these which hit my foot. We were the 28th LCT Flotilla, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Neiberg (or Neiburg). The Beaulieu River was where one loaded one’s tanks.

“I hate water. I joined the RNVR because it was the only part of the navy where you didn’t have to learn to swim! I was a midshipman on D-Day because you couldn’t be an officer until you were 20, although I was second-in-command of LST 809.”

One aspect we tend to forget when discussing the war is just how young some of the participants were. Brian James, born 1926, was only 18 in the year of D-Day. In 1942 Brian James was a Sea Cadet at a sea school run by a Captain Watts on the River Hamble.

“We could see the sky lit at Southampton when they were bombed at night. We used to count the MGBs going out of the Hamble at night, when I was a cadet, and count them coming back in the morning.

“I went to a salvage company because Captain Sands of the Merchant Navy wanted us to man salvage ships. On D-Day plus about 14, I did salvage work ‘over there’. Risden Beasley was the firm I worked for. I was on the Carmonita. We carried explosives to the Juno beach-head. I was a deckhand. I did training, so I was the gunner.

“Towards the end of my stay at the sea school, we had sub-lieutenants who were to pilot landing craft. We used to take them out learning navigation.

“We had four yachts, before my time, went to Dunkirk. The Mandolin is one. It had the marks of bullets in the side.”

(Interview courtesy of the Algerines, a veterans’ organisation for those who worked on minesweepers.)

Training in 1943

In 1943, Mr E Stott of Heywood, Lancashire, watched instructional films in an old cinema with a tin roof which the sailors called the “flea pit”, now the St Mary’s Street Post Office on Hayling Island. They did some marching and fell out at a local pub. After further training at Calshot, he remained with the training flotilla as an instructor and was on a landing craft which sailed past the Isle of Wight to lay cable. He was told it was secret but later found it was in readiness to provide power for the Mulberry Harbour. They returned to Hayling, taking all the landing craft, LCMs Mark II and IV, LCAs and LCVPs to be moored in an inlet across from Thorney Island. Mr W. L. Kirley of Penryn returned to Hayling later on a navigation course. He recalls that the Army ‘18’ type radios were bulky.

Sometimes, the cross over between Army and Navy got even more blurred, as borne out by the testimony of John Dunham.

Marine John Dunham, aged 20 in 1943, studied the theory of engines at HMS Northney II. He had previously been with a mobile company, trained to drive a Bren gun carrier. Driving a landing craft was quite different. He and his colleagues began to feel more at home when they were sent to HMS Northney III and went aboard them for the first time. Before this, Marines had never been expected to drive craft, but they were delighted to do so. After further training elsewhere, they picked up from Hove the craft they were to take to Normandy.

In training Royal Marines to take over the minor landing craft, a single craft was used to ferry each small group and their instructor to their moorings. It was very cold in winter. They were issued with duffel coats. On pulling alongside their craft, they had to jump; if they missed, they were in the water. Mr Stott did so once, he recalls; luckily he could swim.

Communications and signals was a key area where the success or failure of any operation could be determined. This is well illustrated in the story of Malcolm Robinson of Minehead, formerly of Royal Naval Beach Signals, Section No. 5 (referred to here as B5).

Beach Signals section served in several parts of Hampshire, including the Isle of Wight, Cowes, Calshot and Crondall. There is also the story of the Dieppe raid and the Hardelot raid and an extraordinary tale of fully armed sailors ready for the Normandy invasion having a meal at a Lyons corner house café in London. In addition to Malcolm’s own experience, he has collected the experiences of several others in his Beach Signals section, including the signals station set up by them on one of the Gooseberry block ships. He records the hardships they endured during the Great Storm, owing to their situation, in spite of which they coped efficiently with all the signals traffic there for about six weeks. It also gives a good idea of what it was like on and near the Normandy beaches following the Allied invasion.

Malcolm was a Leading Signalman of the Royal Navy, born at Leigh-on-Sea, Essex. He had enrolled in the RNV(W)R - Royal Naval Voluntary Reserve: the W stands for Wireless - in June 1939 and had served two years in a minesweeping trawler. In April 1942, together with others, he was drafted to HMS Dundonald II, near Troon, Ayrshire, where, he says, “We discovered that our purpose in life was to land with advance troops on enemy beaches and there establish communications between the beaches, assault ships and landing craft. We were kitted out in khaki battle-dress, army boots and gaiters but retained our naval headgear. A motley crew we must have looked! After two weeks’ induction into the mysteries of Combined Operation [mainly square bashing], we were moved to Cowes in the Isle of Wight where a force was being gathered to carry out large scale raids on France.

“A considerable number of naval communications personnel, signalmen, telegraphists and coders, were involved, under the command of Lieutenant P Howes, DSC RN (later Rear Admiral), routine activities being carried out under Sub Lieutenant R S Evans, who had trained as a Beach Signals Officer. St. Nazaire and Bruneval, both very successful operations, were in the past. Dieppe was yet to come. Meanwhile, life in Cowes, with billets at the former holiday camp at Gurnard, was very pleasant, and thoughts of what the future might hold did not greatly trouble us.”

The Hardelot raid’s purpose, according to the obituary of Major Gordon Webb, who had taken part in the raid, was to secure some advanced equipment from a radar station said to be situated there, but in the event, the recall was signalled prematurely by accident, making the raid abortive. According to Major Webb, as the Commandos were returning to the boats they were fired on by the boat party. Only then did Webb recall that the leading Commando had a stutter and could not articulate the password! Fortunately no-one was hurt.

Malcolm considers this raid, much hyped by the press although it achieved nothing worthwhile, counted as “useful experience for the real thing.” The account below is simply, he says “a one-person experience of a very minor event in the history of RN Beach Signals.” (A later commando raid did capture examples of enemy radar equipment, together with one of the German radar operators. News of any raid which resulted in Allied troops landing in Occupied Europe at the time was a morale booster for the British population, which had since Dunkirk expected the Nazis would invade UK shores.)

“One afternoon in early June 1942, I was on the promenade with a friend, a regular telegraphist, survivor of the sinking of the cruiser Barham, when Sub Lieutenant Evans approached and said he had a job for us ‘on the other side.’”

They each thought he could only mean on the mainland, just across the Solent. “How stupid can you be?” he adds.

They were soon on their way, with several other telegraphists, in an ‘R’ (Eureka) boat which took them to one of the Belgian or Dutch cross-Channel ferries which had been converted to carry ALCs (later known as LCAs).

“We then realised that something was ‘on’. Briefing must have been minimal. We were told that a Commando raid was to be carried out near Boulogne and which craft we would be in. When we hit the beach, for what would have been a dry landing, it quickly became apparent that we had picked the wrong spot, because as the ramp was lowered, machine-gun fire erupted from both sides and tracers could be seen crossing just in front of our bows. The German fire was very accurate and to step out into that would have probably been suicidal. Consequently, the ramp was hastily raised and the boat officer, a sub lieutenant, decided to pull off, presumably with a view to trying a less unfriendly spot.

“However, we appeared to be well and truly stuck. Situated starboard side, amidships, I was keeping my head well down, the more so as my aerial seemed to be attracting attention from the German gunners. The ‘subby’ instructed me to radio that we were stuck, which I did, only to receive the terse response: ‘Pipe down!’”

By this time, Malcolm says, mortar shells had been added to the machine gun fire. They started to come “uncomfortably close, and it may have been this that prompted our kedge winch into effective action, because, at last, with the help of the engines astern, we managed to ease off the beach.” (This winch pulls on the kedge anchor cable and helps the craft to back off a beach.)

“By then it seemed that everyone else was withdrawing, so we also headed seawards. As dawn broke, an MGB [Motor Gunboat] or ML [Motor Launch] came alongside and took off the commandos, leaving the subby, coxwain, motorman and myself. We were offered a tow, which we accepted gratefully, but the speed of the MGB was too much for us; we had to cast off, otherwise we would soon have been bows under. Suddenly we were alone, with not another craft in sight.

“Then, acting as self-appointed lookout, I spotted over the starboard quarter several ominous-looking fast craft approaching. I called the subby’s attention to this with the words: “Don’t look now, sir, but I think we’re in for trouble!”

“Now, what I did not know then was that the Royal Navy had one flotilla of steam gun boats, commanded by Peter Scott. Much to our relief, we spotted their white ensigns. They hauled alongside, checked that we were OK and steamed off, leaving us to our own devices. It was a pleasant trip after all, one small ALC all by itself, bright sunshine, calm seas, not a plane or ship to be seen and incredibly no trouble on the way.

“We beached at Hastings to find reporters and photographers waiting. I ducked down to ensure my mother would not be shocked to discover what I was doing. She thought I was shore-based. Well, I suppose I was, in a manner of speaking! Even so, the camera caught the top of my head - evidence I treasure because it proves that at one time I had a reasonable head of hair!”

Malcolm, for a short period prior to the cancelled Dieppe operation, was in Calshot. His paper about the activities of his beach communications team, A Job on the Other Side, is quoted from, along with extracts from his letters to me and to Maurice Hillebrandt.

“The above operation in which I took part (Bristle/part of Lancing), was the Hardelot raid of 4th June 1942 - and morning papers of 5th June bore banner headlines in the London Evening Standard, which reported “Commandos are Home, Casualties Slight”, whilst the Daily Sketch declared “Commandos in Woollen Caps and Shorts Raid Nazis - Germans fire at Germans”. The newspapers painted a glowing picture of a successful raid, but I fear the truth was somewhat different.

“A landing was achieved by some, although not all, of the raiding force, but the recall was sounded prematurely before the objective had been attained. Photographs of the ‘returned warriors’ were in the two papers mentioned above. The event was fairly minor in the context of other subsequent activities in which we Naval Beach Signals people were involved.” (Malcolm Robinson.)

Malcolm offered this additional information about the Hardelot raid: “We started off from Cowes, and I am pretty certain that the ship we joined was the Prins Albert, one of the pre-war Belgian cross-channel ferries which had been converted to carry Assault Landing Craft, known as ALC. We chosen ones, from our base at Cowes, joined the Prins Albert somewhere in the Solent. I think Prins Albert carried about eight of these craft, each capable of transporting thirty or forty commandos or infantry together with crew, normally a Sub lieutenant, a coxwain and a motorman, with possibly an additional seaman. There was no training as such for this particular job - we were just, literally, plucked off the street.

“On the Hardelot raid, the commandos were reported as wearing woollen caps. As to the shorts, it was high summer, so shorts were for comfort in the heat. Also, doubtless, less material to get soaked when wading ashore. How did I feel when there were just four of us left in the landing craft on the trip home? Well, a degree nervous, I suppose, but certainly wary, and fully expecting at any moment to be attacked from the air or sea. But I think the predominant mood was that we had got away from Hardelot unscathed and were making reasonable headway in calm waters.

“The degree of training received by Naval Beach Signals personnel varied considerably, from the brief induction I had at Dundonald, coupled with some practice in the use of a .45 revolver, to the more extreme, virtually commando assault courses in the wilds of Scotland. Beach Signals personnel comprised telegraphists, signalmen and coders, all of whom would have received normal naval training for their particular skills. Telegraphists, as such, merely had to be inculcated in the use of portable wireless sets, such as the Type 18, which I carried on the Hardelot raid, and the later Type 45, having crystal controlled channels. Signalling on jobs such as the Hardelot raid was kept to an absolute minimum, for obvious reasons. Visual signals would be used only when necessary and wireless only when instructed.

“As to navigation, on raids such as the Hardelot, the landing craft heading in to the beach after having been dropped from their transport, would usually be led in by one of the coastal Motor Launches or Motor Gun Boats, which would also be on hand to provide fire support, since the armament on an LCA was a single Lewis Gun. A Motor Launch was about 110-120 feet long with fairly light armament.

“After Dieppe, the large conglomeration of communication ratings gathered at Cowes was divided into Sections, each of about thirty men, and the Section I came to be in, then, RN Beach Signals Section No. 5, had, prior to Normandy, participated in the North African landings, the invasion of Sicily and afterwards the toe of Italy and eventually the Anzio landings.

“At the time of Dieppe, I was one of six communications ratings attached to Commander [later Captain] Ryder, the St. Nazaire VC, whom we were to accompany aboard HMS Locust, an old China river gunboat, and we embarked on her from Calshot. In the event, after a week of kicking our heels moored in the Solent, crammed full to overflowing with troops, Mountbatten came aboard to tell us the whole thing was ‘off’. Everyone had been fully briefed on their tasks and the intended destination, Dieppe, so it was not surprising that when the operation was reinstated for the same destination in August 1942 the Germans were well aware what was afoot.

“But after the cancelled event in June, leave had been granted - ‘disappointment leave’ we called it - and the hundred or so communication personnel from Cowes returned to their main base, HMS Dundonald, near Troon, Ayrshire. Towards the end of July we were all moved down to - of all unlikely places - Crondall, in Hampshire, where a couple of weeks or so were enjoyed with occasional route marches, communications exercises, and plentiful visits to one or other of the local pubs. Little did we know what was in store for us!

“The day before the operation, we were transported down to the coast, most of us to Newhaven, where we were allocated to various ships and craft, depending on what tasks we were intended to do, some to landing parties, some to join fleet vessels, destroyers etc. for signals co-ordination purposes, some to the principal landing craft and others to the close support Coastal Forces MLs and MGBs. Our destination was to be Dieppe.

“I was one of the lucky ones, to join an ML, thus missing the carnage on the beaches. Upon our eventual return to Crondall, we were much saddened to find that out of the one hundred or so who set out, something around thirty were missing, killed, captured or wounded.”

Operation Neptune was the code name for the naval part of Overlord, the sea-borne invasion of Normandy, on 6th June, 1944, when Allied armies landed on the beaches of Normandy.

In the naval side of the invasion, 7,000 vessels - of which more than 4,000 ships and landing craft, were engaged in the initial assault and follow-up stages; 1,200 warships were to protect the invasion fleet and to blast enemy defences; in support were 736 ancillary craft and 864 merchant supply ships. Malcolm says that in the context of this mighty assemblage, the part played by one small naval unit of 30 men can only be regarded as infinitesimal, yet every unit, large or small, and every individual had its, or his, part to play on the day. His section, Royal Naval Beach Signals Section 5, RNBSS5, was no exception.

In the weeks preceding D-Day, B5 was based at HMS Vectis at Cowes, and billeted in the former Gurnard Pines holiday camp.

“When B5’s personnel were despatched to their respective craft and duties, probably at least half the section formed the party for the Gooseberry. As well as the Mulberry harbour utilised off Normandy, there was another form of harbour, designated Gooseberry, which consisted of a row of old merchant ships sunk in position nose to tail, so to speak, to form a protective shelter for the smaller craft employed on the beaches. For certain reasons B5 was employed in a subsidiary role for Normandy, its main function being to set up a Signal Station on the Gooseberry off Juno Beach, although some of us, myself included, where given other functions.

“Which reminds me that two of our telegraphists embarked from HMS Tormentor into an LCI [Landing Craft Infantry]. One of four such craft, loaded with infantry and/or stores, was destined to take part in the initial assault on the Normandy beaches.

“Detailed information is lacking but Lieutenant R S Evans was detached to act as Signal Officer to SOBG [Senior Officer Build-up Group] with Headquarters in LCI(H) [a minor headquarters set up in an LCI]. He embarked direct from HMS Vectis, in a Fleet Escort Vessel in company with an RN Lieutenant Comm who was to act as harbour master, controlling the anchorage off Juno Beach. The vessel in which he was embarked escorted landing craft into the beach. Later in D-Day he transferred to the LCI(H) already mentioned. The party for Gooseberry, under Sub Lieutenant M Garvey, included L/Sigs J Cummings and Johnson; Sigs Greenwood, Seldon, Grundy and Pirt, Tels. Challenor and A Chadwick; Coders Godsall, Wallbank, Jeffrey and Mapp. It seems likely that Yeoman Arnold and PO Tel. Spencer took passage in the Escort vessel in which Lieutenant Evans embarked.

“From HMS Tormentor II, Tels. S Edwards and B Stone joined an LCI(M), one of two destined as HQs for D/SOBG (M.T) [Senior Officer Build Up Group organising motor transport] and D/SOBG (Stores) [Senior Officer Build Up Group organising Stores: the Build Up Group were later arrivals to the beaches]. These craft, two of four allocated for Signals purposes, were to beach in the initial assault, but the two carrying passengers and stores, including the one in which Edwards and Stone were embarked, were knocked out when approaching the beach.

“I [Tel. M Robinson] joined an MFV [Motor Fishing Vessel, about 40-50 feet long] at Cowes, which ran errands round the assembled Fleet prior to setting off in the early hours of D-Day, navigating - one can hardly call it ‘escorting’ with armament consisting of one single barrel Lewis gun, two rifles and my revolver - a large number of LCMs across to Juno Beach, where I transferred to the SNOL LCI [Senior Naval Officer, Landing, in a particular part of a beach] late afternoon, D-Day.

“I do not know the duties of the remaining members of the section, It is probable that L/Tel. G Baker would have been in the Gooseberry party plus Coder A Knox, Sigs A Cruise, Sweeney and Emerson, plus one other whose name is forgotten. Tels. Jeffreys, Russel, T.Chapman and R.Scott may well have been allocated to other controlling craft but in the absence of firm information all of this is guesswork. Sig. G Pink seems to have been the only member of B5 to have made a beach landing, but why, how and when is a mystery. Various of the Section, who had occasion to visit the beach during their stay offshore, met up with him, together with a small number of Commandos. He complained bitterly that he was the sole Beach Signals rating there, with nobody to relieve him. I assume that, perhaps at the last moment, he was detailed to accompany a Commando Unit carrying out a special task. No record exists as to what this might have been.

“For reasons mainly to do with the worsening weather, the main assault on Juno Beach began later than scheduled and ran into trouble. The tide had risen over the first lines of beach obstacles with the result that instead of landing in front of them, the first assault waves found themselves landing right on top of the submerged girders and mines.

“Now, the majority of B5 knew nothing of this, being still in transit to their eventual destination, the Gooseberry. This main party had left Gurnard Pines on 2nd or 3rd June, crossed to Portsmouth on the old paddle ferry and thence took the train to Waterloo Station, London, to transit to Fenchurch Street Station for train to Tilbury, to join a ship for the trip down Channel to the Normandy Beaches.

“The party had some time to kick its heels in London. Incredible as it may seem, but nevertheless vouched by existing members of B5, the party was allowed to scatter for food and sustenance, each to his own devices, before reassembling at an appointed time at, presumably, Fenchurch Street Station.

“It is said that some members resident in the London area headed for home. Some, at the suggestion of L/Sig. Johnson, headed for the public house known as Dirty Dick’s in Bishopsgate. Les Seldon remembers hearing this suggested but himself, with three others, decided that food came first. Len Jeffrey remembers going to Dirty Dick’s - cobwebs, sawdust on the floor and stuffed birds on the walls - and says he can’t imagine going to such a place at any other time in his life!

“Les and three others headed for a Lyons Corner House where, arriving fully kitted and armed, to the surprise of a full restaurant, the manager found them a table and a very satisfying meal was provided on the house.

“How it came about that laxity of this kind was permitted in circumstances requiring utmost security is beyond belief. Certainly, had Lieutenant. Ray Evans been in charge, there is no way such risk of breach of security would have been countenanced. In fact, the whole party reassembled on time, which says a lot for the integrity of the individuals concerned.”

They took train to a part of Westcliffe-on-Sea, named HMS Westcliffe, and were accommodated in a semi-detached house overnight prior to going to Tilbury where their transport awaited them - a ship believed to have been the Asturias or the Ascanius (probably the latter as it was nicknamed “the old ashcan”) - which headed downstream to the Straits of Dover as part of “a sizeable convoy, part of the large follow-up force proceeding from East Coast ports.” The convoy was shelled by long-range German guns from the Calais area. “It was about this time that it was announced that Airborne Forces had been dropped during the night and that the invasion had started.”

The B5 party reached and boarded the Gooseberry in the afternoon of D-Day or D+1, when the block ships to form the Gooseberry were being scuttled. As B5’s ship came into the anchorage a vessel leaving ranged along her starboard side, and carried away one of her lifeboats. Their ship having anchored, B5 moved over to one of the block ships already in position. “This, with gear, was no easy task,” Malcolm recalls. Rope ladder down to a landing craft which carried them across to the Gooseberry, then up another rope ladder onto the deck of what was to be their home for the next few weeks. Once aboard, visual contact was quickly made with the Beach Signals people ashore and with other controlling craft.

“From the bridge of the blockship could be seen the scattered remains of landing craft of one sort or another that had been destroyed or damaged by enemy gunfire or by falling foul of the beach defence obstacles. Out of 306 vessels employed on Juno beach on D-Day, 90 were lost or damaged. Of these, the leading 24 became casualties. One of these was the LCI in which Bernard Stone and Stan Edwards were embarked.

“Bernard recollects,” says Malcolm, “that this LCI was carrying troops and equipment, about 50 in all underdeck forward and he and Stan were in a small hatch space in the stern.” They moved off in the early hours of D-Day together with “a stream of other landing craft, reaching the assembly area about 0715 hours,” ready to move in. “The weather had worsened during the crossing and, like many others, Bernard was badly seasick.” His condition was made worse by the smell of diesel fuel from the engine compartment. Shell and mortar fire met their approach to the beach. Their first attempt to get through the barrier of beach obstacles was unsuccessful and they pulled off to try further along. Shells from HMS Warspite passed over their heads, trying to silence a battery situated near the church in Courseilles, the tower of which was being used as a spotting station.

“There was a loud ‘crump’.” Bernard told Malcolm that he thought their LCI had hit another craft, but looking from their hatchway, “he realised the bows of the vessel had gone and it was fast sinking. He recalls that, despite the situation, he did not at that moment feel particularly scared, because he was so sick.” He remembered very little of what happened then until he was sitting on the deck of a destroyer with survivors from other craft, drinking hot soup. As far as he is aware, he and Stan Edwards were the only survivors of those aboard their LCI. He “has the impression that he spent the night on one of the Gooseberry ships but this is by no means certain.” He found himself next day, D+1, aboard the SNOL LCI, which I had joined the previous day, but his recall of the first few days is practically non-existent. “The fact that on that first morning, he gave his tot [of rum] - neaters at that - to me is something of which he has no recollection whatever.

“What brought this about was that, early in the morning of D+1, the fingers of my left hand had been caught between a hatch coaming and a falling hatch cover, not properly secured. The coxwain had dressed it with Elastoplast but I was in considerable pain. I well remember the beneficial effect of the rum, but Bernard, when reminded years later, could hardly credit how generous he had been!”

On board the SNOL LCI, Bernard and Malcolm were reasonably well provided for with food and accommodation. Working watches with SNOL, Malcolm says, “We felt we were fortunate compared with so many others at that time. Three of us watch keepers worked fairly long hours, four hours on and three off until 4.00-6.00 and 6.00-8.00 in the evening. We were receiving and transmitting radio signals.”

For those on the Gooseberry, where Stan Edwards had ended up, by all accounts, life was no bed of roses. In the early stages, rations and fresh water were in short supply; fresh water was a problem throughout.

“Resting on the bottom, the vessel’s upper deck and superstructure were still above water. The original crew’s quarters at the after end, which had some wooden bunks and a mess table, were used as living accommodation. Toilet facilities were either inaccessible or out of action. To reach the bridge, amidships, involved crossing the well deck from the after accommodation, which created a problem when, later on, the weather deteriorated even more. It seems that the ship’s departing crew must have taken with them all items of food and initially the members of B5 were restricted to the emergency rations they carried, supplemented by the emergency rations, such as Horlicks tablets, from the lifeboats.

“The food situation improved when a naval party, whose job was to repair and maintain landing craft, came aboard with supplies and a cook; the galley was brought into use. Fresh water continued in short supply, being restricted to what was brought aboard from time to time. Personal hygiene was also a problem, with only sea water for washing and dhobiing purposes and a lack of soap.

“The section on Gooseberry was kept very busy. For the amount of traffic it was called upon to handle, not only relaying signals from the beaches seawards but also dealing with signals originating from the various Senior Officers who set up their headquarters either in or in the vicinity of the Gooseberry, it was understaffed, but by all accounts performed very efficiently.

“A notable aspect of the Overlord/Neptune operation was the almost complete absence of enemy air activity, markedly different from previous operations in which B5 were involved.”

However, towards night, Malcolm says that aircraft engines were heard and a single low-flying plane came into sight, from inland, carrying a smaller plane on its back, which detached itself and flew back presumably to its base. The larger plane went further seaward by itself and dived into the water with a loud explosion. It may have been intended to strike one of the major Allied warships beyond the anchorage, but no Allied ship was affected. He also says that at night, the Germans tried to infiltrate small two-man submarines and self-propelled motor boats filled with explosives amongst the shipping in the anchorages, not just at Juno beaches but elsewhere. These, he says “are believed to have had limited success, mostly being spotted and destroyed before they could do any harm.”

“A singular event recalled by those on the Gooseberry as well as by Bernard and me on the SNOL LCI, was the sighting of what is believed to have been the first V1 [“doodlebug” or “buzz bomb”]. This strange object with the body of a small plane, stubby wings and fire belching from its rear, flew across the anchorage seawards, with Ack-ack directed towards it by every craft within range, but without success. However, possibly diverted by a close shell-burst, it reversed course and headed back across the coast inland until it disappeared from sight. Everyone hoped that the enemy had scored an own goal!”

“On 19th June, with the beachheads secure and the build-up going well, the whole invasion coast was hit by a gale of unparalleled ferocity which lasted for three days, creating chaos amongst the ships and craft lying off or working the beaches. For the crews of the smaller landing craft and barges the effect must have been terrifying, with anchors dragging and even the shelter of the Gooseberries not at all secure. Even the Mulberry off Arromanches in the British sector was badly affected. [The American one became unusable.] The beaches became strewn with debris as more and more vessels were driven ashore. Had the storm arisen during the early days of the landings it might well have proved disastrous to the whole enterprise. As it was, ammunition stocks ran low, the Allied offensive was delayed, and Rommel was able to build up his defences.

“The situation for those on the Gooseberry was one of extreme discomfort coupled with an element of danger. Although ballasted down and lying on the sea bed, the force of the winds and heavy seas caused the vessel to develop a most disconcerting rolling motion, with much ominous scraping and grinding. At times it was touch and go whether she would turn over. In fact, Alf Grundy well remembers that one night, the vessel next to them started to roll over and the British Army anti-aircraft gunners aboard had to be brought onto the B5 ship hand-over-hand on ropes.

“Resting on the bottom as she was, the vessel’s well decks had little freeboard, and whilst the storm raged, heavy seas were breaking continually across the wells, so much so that it was too dangerous for anyone to cross except at low water, and even then with extreme difficulty and at some risk. Thus the watch-keepers on the bridge and those off watch aft were completely cut off from each other for long periods.

“Conditions on the bridge were atrocious, and visual signalling was a never-ending struggle against the elements, what with the force of the winds and driving rain lashing into the watch-keepers’ faces and soaking them to the skin.

“Conditions aft were decidedly uncomfortable, due to water swirling into the accommodation over the entry coaming. Ron Wallbank remembers waking up to find a melange of personal gear, kitbags, boots etc., floating around the mess-deck in about three feet of water.

“During the storm a signal was received that a midshipman had been washed overboard from an LCT and crews were asked to keep a sharp lookout. Some time later an LCA brought his body to the Gooseberry for someone to deal with. The body was in a bad state and very unpleasant to handle. An officer offered two tots of neat rum to anyone who would clean the corpse and tie it up in canvas. L/Sig Johnson (‘Johnno’) agreed to take on this task, and when it was accomplished, a landing craft was prevailed upon to take the corpse to the beach.

“At last, the weather eased. ‘The Great Storm’ came to an end and things started to get back to something approaching normal.

“Work began, to deal with the stranded craft, including the refloating of a Destroyer, HMS Fury.”

(Ron Miles in Miles Aweigh records that this had been swept broadside on. It was eventually refloated on the evening tide after a channel had been made for her by a bulldozer. In the process everyone got smothered in the jettisoned oil covering the beach.)

“Repair parties from HMS Albatross and HMS Adventure worked night and day on the stranded vessels and of the 800 which were put out of action, around 600 were repaired and refloated by the next spring tide on 8th July, whilst 100 were refloated a fortnight later.”

On the Gooseberry, during the storm, fresh water had had to be rationed and food supplies were practically exhausted. The story goes that in order to try to improve the somewhat monotonous diet, ‘Johnno’ decided to make a foray ashore in search of vegetables. With the aid no doubt of a bit of bartering, he returned with a supply of potatoes. To ensure that B5 would benefit from this welcome largesse, Johnno took personal responsibility for their preparation and cooking in a large fanny (type of kettle). When they were boiled, he handed the fanny to Sig. Greenwood, known as Jan, with instructions to drain them over the side.

“Now, Jan was a country boy who, having experience of driving tractors and other vehicles on a farm, had been responsible for driving B5 all over Scotland in a three ton truck. At this job he was superb,” but at cooking was a complete novice. Not being quite sure what Johnno wanted done, he asked: “Do you mean all of it?” To which Johnno, thinking of the water only, replied ‘Yes, the whole ******* lot.’ At this, Jan lifted the fanny and tipped both water and potatoes into the sea. The reaction of Johnno is best left to the imagination. Jan was lucky he did not finish up where the potatoes had gone!

“Nevertheless, pressure of work did not diminish and the B5 crew were kept extremely busy. The capture of Caen was preceded by an awesome air strike by RAF Halifaxes and Lancasters. Those on Gooseberry had a grandstand view of events, hundreds of these big four engined planes passing almost directly overhead to paste the German defences.

“The watchers could see the planes flying through a tremendous barrage of Ack-ack, dropping their bombs and turning back towards the coast and safety. Inevitably some of them did not make it, the aircraft being shot down but the crews mostly able to bale out, their parachutes descending into friendly territory. Sadly, now and again, parachutes were seen not to open, the airmen plunging to certain death.

“The beginning of July marked the effective end of Operation Neptune, but the beaches continued working until the end of July. When B5 had been on Gooseberry almost six weeks a landing craft pulled alongside containing a number of communications personnel, the advance of the relief for B5. To ensure continued smooth working of the station, half of B5 were to leave the next morning; the rest would follow later. The first party to leave were taken ashore by landing craft and instructed by the Beach Master to go back to Gosport in a landing craft which would be returning empty. They arrived in it off Fort Gilkicker around midnight and three Royal Marines (awoken from their beds) were detailed to offload the B5 party at Ryde Pier.”

A long wait ensued, with no transport available to run them back to Gurnard Pines. They told Malcolm afterwards that they struggled along the length of Ryde Pier in the dark, and Sub. Lieut. Garvey went off to find a telephone to arrange transport whilst the others took shelter under the canopy of the railway station. They heard a “doodlebug” pass overhead which was seen to fall “somewhere in the Southampton area,” as far as they could judge. Les, who knew Ryde well from pre-war, suddenly realised that the canopy above them was made of glass, which was not the best protection should one of these rockets fall nearby. A move was made quickly to the open seafront.

While they were waiting, several more “doodlebugs” came over, all going towards the Southampton area. It was cold on the seafront, despite the time of year, but the low temperature was alleviated to some extent by the new-style cans of soup they had with them, which had an inbuilt heating device operated by pulling a cord and waiting a couple of minutes for the contents to warm up. Still feeling chilly, one of the party broke some pieces of shrub and somehow managed to start a small fire, but no sooner had it begun to warm them up than an Air Raid Warden appeared and ordered them to put it out, threatening arrest if they did not comply. Fortunately a lorry pulled up alongside to pick them up. By the time they reached Gurnard Pines it was morning. They showered and changed their clothes and enjoyed a hearty breakfast, the first really good meal they had had for many weeks.

“Afterwards,” Malcolm says, “They met up with Bernard and me. We had returned to UK about 10/14 days earlier, crossing from France in an LCT which bowed between bow and bridge, up and down, in a most alarming manner. We were convinced the craft had broken its back; most likely it was the normal action of an empty LCT.

“When we arrived back at Gurnard Pines, nobody seemed to want to know anything about us. We settled into a chalet, slept in until 10.30 or 11.00 every day, emerging only for dinner and a gentle stroll down to Cowes. After about a week of this near-Nirvana, we were rudely aroused one morning by a Petty Officer checking the chalets, who threatened us with all kinds of dire penalties, which somehow did not materialise, but in no time at all we found ourselves down in Cowes scrubbing floors and performing menial tasks.

“The second half of B5 returned to UK shortly after the first lot, crossing in an LST loaded with wounded, German as well as British and Canadian. Prior to embarkation Alf Grundy and Len Jeffrey had helped to take some of the wounded onto the LST. Alf recalled that some of them, presumably tank crews, were badly burned and he helped the medical staff with the dressings on at least one of them. Len recalled that one young soldier took his hand and squeezed it so hard he thought his fingers would break. Shortly afterwards he was talking to men of 1st Battalion East Lancashire Regiment, who told him that their 5th Battalion had suffered very heavy casualties. Len’s brother was in the 5th Battalion and was amongst those killed. His death was confirmed the day Len arrived home on leave.

After their return, members of B5 were granted leave. None of them are quite sure how long the leave was, possibly ten days, nor when it was. Some weeks later, the whole of the Section were in Nissen huts at Exbury House, where they were “at a loose end” says Malcolm. “Nobody quite knew what to do with us. Some of them somehow managed to take a few days ‘unofficial leave’ without being missed or repercussions ensuing.” Malcolm says he accompanied Johnno to Leigh-on-Sea.

Not long after the story of the Battle of Arnhem and the evacuation of the survivors was broadcast, B5 heard the section was to be disbanded. Malcolm, who had been offered the prospect of a change from Beach Signals by the CO of SNOL LC1, and had opted to remain with it, found this ironic. Some of the section returned to General Service, one went to another Section and some kicked their heels still more all through the winter of 1944/45. Two, Bernard Stone and Stan Edwards, joined B3 which went to the Far East, and took part in the assault on the Morib Beaches at Port Swettenham (Operation Zipper). “Fortunately for all concerned,” says Malcolm, “The surrender of the Japanese meant they landed as a re-occupation force instead of an invasion force.

“Alf Grundy had the vague idea that after B5 was disbanded he took part in the re-occupation of the Channel Isles but he remembers being demobbed in February 1946.

“Len Jeffrey found himself in Devonport, instructing on Type X Code/Cypher machines. He was then drafted to the destroyer Fame as Leading Coder.

“I was at Dundonald until the beginning of May ’45 when I was drafted to one of two flotillas of Beach Survey Craft [Eureka Boats] based in Argyllshire, working up for service in the Far East.” In the winter of ’44-’45, the cold bit into the damaged fingers of his left hand and what was worse, he had “some affliction which resembled glandular fever.” Life improved for him when he was joined for five months by his wife and two-year-old son. He was also joined at work by another former B5 member, Alan Chadwick. He was already in touch with Tom Chapman, who had his wife in Troon and who had suggested Malcolm invited his own wife and son to stay nearby.

Malcolm says their flotilla was not sent East, the war having then ended. He was demobbed in November ’45.

Malcolm adds that two former members of B5, not with the section during the Normandy landings but still in touch with those remaining, were Jack Payton, an RAF Wireless Operator, and Norman Weston, a Naval Signalman. Jack returned to the RAF and soon found himself in India. Norman was in B7 for Normandy and landed on Juno Beach. After three weeks there, his Section was relieved by a newly formed Canadian Beach Party and after a brief spell in UK, they went back to France with a party of civilian intelligence people, for whom they maintained communications through Belgium, Holland and Germany, finishing up at Flensburg, Denmark.

It quickly became evident when the fight proper was joined with the German Kriegesmarine, that air power was going to be a crucial part of the struggle for the dominance of the seas. The attack on the Bismarck by the stick-and-string biplanes of Eugene Esmonde’s Swordfish squadron was a classic illustration of the way in which a sleek, modern battleship could be hobbled by older technology, if caught out in the open by air attack, and undefended.

The story told by Lieutenant Humphrey Dimmock is no doubt typical of many.

“I was, before the war, a professional pilot, giving instruction. I volunteered. I trained at Eastleigh - the war-time training. We flew TAG - Telegraphy, Air Gunners. We took them out. All we had to do was fly them and back again. I suppose we were learning how to fly naval aircraft, and naval discipline. After that, I volunteered for first line work and my name went up amongst others, and I was sent to a place where we learned to fly Swordfish, and drop torpedoes and bombs. And I passed off of that, I know, with top marks. Then I was posted to 823 Squadron in the Orkney Islands, where the work I was doing [was] searching for German submarines with depth charges on your wings, up in the Arctic. We flew open aircraft. We had to wear gloves. You couldn’t do any writing on paper, you were flying all the time. You had to do all calculations in your head and I’m good at that.”

He was posted to 781, flying VIPs, mainly because before the war he had been a professional pilot.

“I always considered myself top of my rate. I was cocky in those days, you know? Then I was posted to 781 where I was senior pilot immediately and eventually became CO and told others what to do. But I had to lead them on and I taught a lot of people some of my ..tricks if you like; sort of how to do things. Training. Good training.

“I lived in Gosport at the time. I was at Bangor on the front. Had my own little boat and would go fishing at night. I was posted to Number Three Wing.” [Number three wing was flying Spitfires.]

“When did you learn to fly Spitfires?”

“Oh, years before that. There were six of us. All the Spitfires in the country, from the Royal Air Force, and manufacturers, and took them to a place in Scotland, where they were training Spitfire pilots for dummy deck landings. Which meant you hit the deck pretty hard. And I hadn’t done dummy deck landings in a Swordfish. I knew what they were up to: they were breaking them at a rate of ten a week, then having broken them, they were mended there. And we took all the Spitfires, after breaking and temporary repair, we were flying back to Royal Naval Air Repair Yard at Fleetlands, or to Hamble, where they had hooks put on and they were called Hookfires for actual deck landing. And they had the strength in them to stop them crashing, I’m sure.

“The six of us collected all those Spitfires, and flew some of them as many as three times there and back again and back again, and we never had an accident. We were never late on going places. We were totally dedicated. We made an ETA [estimated time of arrival] before we left, and we jolly well stuck to it. We had a female pilot flew from here down to Cornwall to see her boyfriend (before I’d taken that Hurricane for delivery at Manston in Kent). A shocking thing to do! We heard it afterwards, mind you, but she should have been strangled. Fancy doing anything like that in war-time!”

“What’s the Spitfire like to fly?”

“Much better than Hurricanes. Hurricanes, you had to fly it all the time, as if you were in a link trainer. If you flew in cloud in a Hurricane, you had to watch the instruments all the time. Because the nose, without you doing anything, it rises more quickly, it goes down more suddenly. Got to watch the instruments carefully, and try and fly it straight and level. The Spitfire, it was well balanced; you could take your hands and feet off it and - no bother, she’d carry on flying. Spitfire’s a beautiful aeroplane. Much preferable than a Hurricane, to me. I didn’t get Seafires at all, that was postwar. Seafires really are modified Spitfires.”

“So, this was all at Daedalus. What was Daedalus like then? Was it the same as it is now?”

“It hasn’t changed much in the field and the buildings all are as they were then. And the runways as well.”

“So what was your involvement with the rest of the war? Did you continue flying to France?”

“During the rest of the war? One of my junior pilots said to me: ‘We keep going across to France to all these things. It would be better if we kept a flight in France.’ I said: ‘Yes, I agree with you entirely. You’ll be in charge of it.’ And he was Anglo-French, French mother and an English father. He was completely bilingual. I’m still in touch with him, in France. So he had charge of a flight, which followed the armies through - his first posting was up the Seine. First big town you come to. What is it?”

“Rouen?”

“Rouen? Yes, that would be it. And right into Germany in the end. And here was another very emotional thing. As my flight moved forward taking stores and aircraft parts and people, I went over there too. If I could go, I took them. I loved going. And as Germany was being beaten and they had prisoner of war camps, as the prisoners of war were released, the freed personnel were collected by my flight and brought back to Daedalus”. Here he documented them and sent them on their way “in two hours”.

“On D-Day itself [does he mean VE Day?], celebrations were terrific and a message from the Admiral came that, ‘there were three German POWs; would I get them away home by air as usual?’ It was virtually impossible. I said, ‘Yes, I think I can do that.’”

There was difficulty finding a serviceable aircraft. Also he was told, “‘Wherever you go in the country, you can’t land at any aerodrome with permission, you can’t take off with permission, and you’ll get no assistance whatever. You break down, they might have a fire crew, they might not. The whole country will be drunk!’ [Laughs] Well, certainly I was, in the morning. I was carried home and put to bed to recover and I had permission to take my two boys aged 12 and nine with me. My older boy, before the war he, at age five, had flown with me always. The ex-POWs were interested and I just expounded myself with all their questions. It was quite something. And having done all this I took my two boys over the invasion beaches to see what had been going on there. I was flying till after VJ day. Right up to 1946.”

“When did you actually learn of the invasion?”

“On D-Day. Mind you, we knew something was up, because every road from beyond Winchester, every minor road was full of army vehicles. And on the front at Lee-on-Solent, both sides, you could just drive one car at a time. A few gaps to let other people pass. All along there, full of vehicles. Gallons, vans, shell carriers, little vehicles. In fact, something big was happening here and we knew it.”

“So how did you feel when you knew it would actually happen?”

“Oh, terribly thrilled. It’s what we’d been aiming at, all the four years we’d been thinking of it and at one time, in the Orkney Islands, with seven weeks’ expectation of life, we had no hope of life. We thought Germany was going to win the war and we’d be killed anyway, so why bother. That was the attitude.”

“So the invasion was a great morale booster?”

“Ooh, terrific.”

“On the 6th of June, could you run through your first sortie of that day?”

“Well, we took off in pairs. Number one was the spotter pilot, number two, that was me, was the fighter pilot behind him, to keep enemy aircraft away from him. And while we were in France, we notified a ship, name of Sunshine: ‘We have arrived in France, What target, please?’ and it said to us ‘Target Number 1’. We’d been briefed as to what this target was, we both had maps, and as soon as my number one had found it - he was called Skylark and I was Skylark 2 - he called ‘Sunshine, I’m over the target now, what instructions?’ So the ship said: ‘Flash, 17 seconds.’ That means that in 17 seconds a pair of shells will hit the target, or miss it. Five seconds before it was due to hit the target, he says: ‘Flash, five seconds.’ That gives the spotting pilot time to tip his aircraft on the side and look out of the window at the target and look where the shells hit. The first shot he said, as best as I remember, ‘About 200 yards overshoot but direction good’. So Sunshine said, ‘Right. Stand by. We’ll try again.’ His next shot landed. And I wasn’t watching the shells until after they had burst. I could see from the smoke. Skylark 1 said, ‘Jolly good shot. Right on the target! I’ll go down and investigate.’ And he went down to investigate at a very low level … and, ‘Bloody Hell, they’re shooting at me. I’ll go up again. Give them some more!’ That is very literal. I think we had two more targets and after that we go home. I’ve no idea what the targets were. A farmhouse on the map. We were all good at map-reading.”

“Now, you were flying over the invasion fleet, so what was that like?”

“Oh, the Channel was full of ships going back and going forwards and anchored near the shore. The Mulberry harbours and the ships sunk along with them - we had full vision of all that. And tanks - a hell of a movement on the ground, we could see. But it wasn’t our job to look at that; our job was to do [what] we were told to do, and we did it. We were frightfully, frightfully, conscientious - and thrilled. We flew only one sortie that day, because an ex-CO’s squadron had been shot down and he decided that, as they’d been cannon fodder for the Germans, he’d not let the experienced pilots go in. And I was experienced fully in what I was doing. I mean, had I met a German aircraft - I did see a group of three but I shot at them a long way away, they would have seen the tracer bullets going past them. But they just didn’t swerve, they just go shshsh - gone. I didn’t think of chasing them either.

“I was on communications, taking people to and from France and landing in France. The Americans were all ready for it. They had little carpets they put down on the fields. There were metal carpets on which you landed. That was very clever. And then I was taking people and stores there and back and that sort of thing.”

“You actually flew to France?”

“Oh, yes, a lot. Two days after going there, a most extraordinary thing happened. They had WAAFs and Wrens and Army females and nurses, and they threw a dance in a big marquee, with floorboards and band and we were dancing there and shells were screaming overhead. All lights on and no thought of any danger, just dancing and - happiness.”

The navy was another service which saw the war transforming the lives and prospects of women recruits. At the beginning of the war, it seems that those called up for the WRNS were mostly used for traditionally female roles - as cooks, stewards, typists and to look after other people. As time went on, it becomes clear that a number of very young girls were given key jobs of strategic importance and coped. The first of these interviews are by the author, with later short extracts from interviews from ‘The Vital Link’ exhibition at the Royal Naval Museum by Dr Chis Howard Bailey, used courtesy of the Royal Naval Museum.

One such was Wren Patricia Balfour, born 1919

“On 3rd September, the day war broke out, I was on Portsdown Hill with my boyfriend and we heard the 11 o’clock news and within a few minutes there was an awful noise and we thought ‘My Goodness, they’d got here quickly!’ But it wasn’t [the enemy]. It was a thunder storm!

“I applied for the Wrens and they didn’t have a place for me at first, so I did VAD training at the Cottage Hospital in Emsworth. Then they called me up for the Wrens so I went to HMS Vernon in Portsmouth. I lived at home with my mother, so I had to travel in by train every day. They had the Hayling Billy then [steam train] to Havant. There was a bomb on the line once, Hitler bombed the Portsmouth line, you see, but I managed to get in to work, because somebody I knew from Hayling came along with a car, which was full but I managed to squeeze in. It got me to Portsmouth. I had to sit on a sailor’s knee! I got in to work all right. It was quite a long way. What did I get? About 12s.6d. a week, it may have been 15 bob. I think my friend had 12s.6d. a week because she was mobile. She lived in quarters. My mother helped me with the fare. I was 21 by then - I had my 21st, you see, in 1940.

“I hadn’t done a job before I went in the Wrens, to be perfectly honest. At Emsworth Hospital, I suppose they paid me my fare or something. I joined the Wrens in May and they gave me the uniform and I took it away and said I was having it made to fit, and come September, I put it on. It was rough naval material, ‘Pusser’s serge’, [Purser’s serge], you know? So I duly put it on and we had a heat wave! They were black cotton stockings, black shoes. As an officer I had brown gloves but I can’t remember what I had when I was a rating. When I was commissioned, I came back to Portsmouth to do my Cypher training and first of all I had to go to Chatham and the tunnel. Cyphering is encyphering words. First of all you put them into groups of figures and then you recypher them, with more, to keep it secret. It was hoped the Germans wouldn’t be able to de-cypher them, you see. They changed the cypher books regularly. I did coding first, as a rating, and when you get a commission then you go on to cypher.

“So I worked in Vernon. It was so nice at first, because, you know, the officers, they didn’t know how to treat us, really, so they used to open doors for us. I was the lowest form of animal life, a messenger, and it seemed … they were charming. I was in the SDO they called it - Signal Distributing Office. These messages came in by telephone, I expect, in those days and they were written down and you had to take them round wherever you had to go, in Vernon. Our Chief Yeoman, who ran the SDO, he was deaf, but he could hear on the telephone, whereas we couldn’t hear, because there was a noise going on in the office, so he could hear with one ear and didn’t bother about the other. I was only a messenger - I didn’t have to learn Morse - mostly I walked but I did have a bicycle. I think it must have been their [the Navy’s] bicycle.”

Pat recalls the day the Free French arrived: “I hopped on this bicycle and off I went - it had no brakes - and I saw this horde of men, you see, and they had sent me to ‘the Commander’, the English commander. So I went up to a nice looking commander and said, ‘Please could you tell me which is the Commander?’ and he said, ‘I am it!’ so I had picked the right one! The French were swarming all over the place. I didn’t take much notice of them …

“And then there was the other occasion when I was delivering the signals and I had to go to the mining shed and … I always go clockwise, so I went to the mining shed first of all, and then I went along to the quay, to deliver something, and I was walking back past the mining shed when there was a very loud bang. Part of a German mine they were taking to pieces to find out how it was made, exploded. If it had been the whole mine I think the whole of Vernon would have gone up, but as it was, it was only a part of it. So I’m afraid they were killed, poor devils, the men who had been doing it. I just left and went back to the office, to get another message to take.

“And when we went into the air raid shelter, which we didn’t do very often, I was known as the Wren with the calm face, because I didn’t show fear or anything. I didn’t really think a lot about it, to be perfectly honest. And I remember walking along the road from Vernon towards the station with, I think the Commander or Captain or something, and there was an air raid on but he didn’t bother much about it Just walked on.”

Similar experiences were shared by Margaret Lilian Wheatley, born 20th October 1919

Margaret joined the Wrens in the summer of 1941.

“I was a Messenger first, in the Wrens. And then I got up-rated to a Writer.” Born in Portsmouth, she was living on Somers Road when war began. “I lived with my mother and sister and grandmother. I was a machinist for a while. I wanted to be a librarian but my mother was on her own and she needed the money really, so I didn’t do what I really wanted. I did get on a little bit better in the Wrens.”

“Was Portsmouth being bombed by then?”

“Oh, yes. Yes. Badly that year, January 10th 1941.”

“Did it affect you personally?”

“It did. Eventually we did get bombed out. We moved more into Southsea.”

She was in Portsmouth when the D-Day landings took place. “I remember people went down to the Guildhall, because that was a focal point in those days. They’ve built all round it now - it was ever such a big space there - any big event, people would go to the Guildhall. I met some relatives when I got there. People just talked of one topic at the time, you know.?”

“Can you describe the day you joined up? What was it like?”

“Oh, there was a place called Bowlands in Southsea - it was a naval nursing home. Which I eventually went to when I had my second child - son. But I went there for training two weeks, then I went to the naval barracks in Queen Street, it was HMS Victory then - it’s HMS Nelson now. I went there and I worked in the mail office for a while. Then I went to drafting office and they had taken over several private houses (I think that belonged to naval officers - they had let them out to the Admiralty) and Woodford’s School, that’s not far off Palmerston Road. And I worked there for quite a while, moved from one house to another, and I was just a Writer ‘G’ which was ‘General’. I wasn’t a typist, you know. I did go to night school for a while but not for very long … That was the Navy, you didn’t have to pay, you could go and learn anything. I started French and didn’t stay long on that. I did it eventually in later life but … oh and typing. I didn’t keep that up.

Welcome news arrives, from home or family!

“I know something I did do while I was in the Wrens. There weren’t many staff on the telephonists - they had a couple of girls and so they taught some of us and we did that for a while and we were all a bit nervous …because it wasn’t our job, you know - but there was a nice Wren, I think she was a PO Wren, she was very patient and she got us all through it. We did all right. She was so patient and nice. If she’d bullied us into it we wouldn’t have done so well, but she was very good.

“I think we used to work [as telephonists] when we were on duty in the evenings. It wasn’t very often. And there was a direct line to the Admiralty and I was a bit nervous - ‘Will it ever go when I’m on duty?’ And it did! I managed to get through that all right. I didn’t deal with it, of course - the senior rating would have dealt with it, whoever was in charge on that duty night. I just had the call and then of course I passed it over to somebody senior …

“I became a Leading Wren. And I was offered to …for the officer course, but by that time I was engaged to my husband and when he became a PO I think the Wren officer in charge of us wanted me to come up as well, but I didn’t because I didn’t think I was qualified enough, really. I thought, ‘Oh dear, I’ll be in charge of people,’ and I was a little bit worried about that. I might have accepted it after, but then I got married in 1943 and there was over a year, I think, and then I became pregnant with my daughter and I left in 1945.”

“Did you have to leave when you were pregnant?”

“Well, yes. I used to get very sick, that was the trouble. I didn’t show. I think you could stay till you were five months, but if you… “

“You wouldn’t be doing any heavy lifting or anything?”

“Oh, no, I used to sit down. But I used to get so sick. So I left then.

“I’ve never met a Wren yet who didn’t like it [being a Wren]. I’ve met some very nice people, very nice. There’s only one that I know that worked where I was, we didn’t work together, either. You always hoped… friendships have been made since leaving the Wrens, with other ex-Wrens because they share the same background.”

This ex Wren Ship’s Cook, born in Portsmouth, prefers not to be named:

“I have lived in Portsmouth all my life, apart from going over to Lee-on-Solent during the war. I would have been called up, I was in private service as a cook but …I didn’t like the other uniforms, that was it. I didn’t like the khaki [ATS] or the blue of the Air Force, so I decided to apply to the WRNS. I went into the WRNS in 1942 as a cook and I didn’t actually work in barracks at all, because where I was at Lee on Solent, all the houses were commandeered for the Wrens’ Quarters, because they had too many men in the barracks and we used to have two houses either opposite each other or next door to each other that housed about 75 to 100 Wrens. One actually slept most of them and the others used to victual them, feed them. And there was two cooks and two ordinary waiting cooks and two officers’ cooks, because we had two officers sleeping there. They were WRNS officers. We used to work on shifts, there was the officer’s cook used to help us as well, but she was mainly to do the officers meals. I was only an ordinary - what they called a Ship’s Cook. I used to do one long duty day and one short duty day. Half past six in the morning to eight o’clock at night. And the short duty which was alternate days was half past six in the morning ‘til two. So it was more or less a day’s work every time.”

“Did the officers have different food?”

“No, it was the same as our food but it was presented differently. While we used to have ours on big trays they used to have theirs like you would at home, on a small tray. And of course, they had officer’s stewards to wait on them and that. They [the Wrens] had to come to the hatch to get their own food. But it was good fun. And we made a lot of friends there.”

She had never before worked with a large group of women. “It was a big shock when I first went in and when I came out in 1946, I was asked to go back to the same place as I was in service [before the war] and I refused. I couldn’t go back to being a ‘one person’. So I went into catering and I’ve been doing catering all the rest of my life. I was able to do restaurant cooking, and they used to do outside functions, you know?

“Well just before I went to Lee [Lee-on-Solent] it was when one of our own shells backfired and went right through the mess room of the girls having their supper. And of course - one of our own shells, went the wrong way. Kind of came back, sort of thing. That was about a couple of months before I went there. And that was pretty horrific.

“After doing a day’s work, being called to staff, we had to do the firewatching as well, so I am off duty at 8 o’clock, ten o’clock the sirens would go and you’d have to get up all night. You were very tired at the end of the time but you just coped.

Everybody else had to cope. Yes, we had quite a bit of gun-fire, not a lot of actual bombs over Lee because it was Portsmouth and Southampton, we would only get plenty bombs on those two big places, we did get the occasional one but nothing very much.” Asked about gun batteries nearby, she recalled, “Oh, yes! They were all round.”