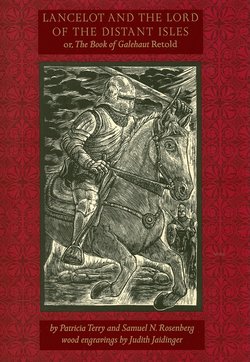

Читать книгу Lancelot and the Lord of the Distant Isles - Patricia Terry - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеOne of the greatest distinctions of the Arthurian legend is the widespread longing that it be real. If Arthur did, in fact, exist, he was probably the leader of the native people of Britain, at a time when their lands were being invaded and settled by Saxons and other Germanic groups. (These newcomers would later be called “the English.”) Sometime toward the end of the fifth century, the Britons began to fight back. There was a decisive battle, and then, for perhaps half a century, the Saxons were held at bay. The memory of the chieftain responsible for that victory would have lingered long after the Saxons’ ultimate success. There must have been nostalgia for a time when extraordinary valor, combined with a sense of being in the right, had prevailed over formidable, and foreign, opponents. Such was the stuff of legends carried through Wales and across the Channel into Brittany by descendants of the Celtic Britons. Even today, there are autonomy-minded Bretons in France who evoke their lost leader, “the once and future king.” Chroniclers did not give him a name until the ninth century, but long before that he had come to be known as Arthur.

In the early twelfth century, when King Arthur was well established in chronicles, stories, and local traditions, Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote, in Latin, a largely imaginary History of Britain. From this source the most familiar aspects of Arthur’s story were to be gradually elaborated, mainly in French: his birth, contrived by Merlin’s sorcery; the sword Excalibur, forged in Avalon; the Round Table and the knights who had their places at it; Gawain the loyal nephew and Mordred the rebellious son; Kay the seneschal; Guenevere, Arthur’s queen. To Arthur came knights from many countries, forming a company of the elite. Women, Geoffrey wrote, in a suggestion of enormous consequence, would give their hearts only to the brave.

Arthur, in Geoffrey’s telling, is a great monarch. He conquers Saxons, Scots, Picts, in his own island, often with great cruelty, then makes war on Gaul, and finally attacks even Rome. His preferred city is Carleon, where he is crowned in an impressive ceremony attended by four kings. Arthur’s armies are formidable, but he himself is always in the foreground, the greatest of warriors, capable of overcoming even a monstrous giant. He attracts worthy men by his reputation for valor, and is also celebrated for his generosity. When he ultimately falls in battle, it is only through the treachery of one of his own, Mordred, and it is suggested that there will be a wondrous healing of his wounds on the mythic isle of Avalon.

Geoffrey’s book, however fanciful, is in the form of a chronicle, purporting to be the translation of an ancient British source. Geoffrey is rightly credited, however, with being the father of Arthurian romance, fiction derived from his work as well as other sources and no longer composed in Latin. Chrétien de Troyes, writing in French verse, developed his own version of Arthur’s court as a setting for plots which reflected contemporary interest in elegance of manners, youth and beauty, ceremonial festivities, the quest for personal glory, and love. This is the modern vision of Camelot, although Chrétien almost always placed the court in Carleon.

Instead of armies in which individual exploits are subordinated to the glory of the king, Chrétien gives center-stage to the knights themselves. They leave the court in search of adventures to test their valor, and often their quest is complicated by the rival demands of love. They work out their destinies alone, sending messages back to let Arthur know their progress. While they pride themselves on being members of his court, the king himself is essentially inactive.

Thanks to the Norman Conquest in 1066, Chrétien knew France and the land beyond the Channel as a reasonably cohesive cultural entity. But King Arthur was British, the symbolic ruler of a race that prevailed before both Normans and Saxons. His knights and vassals, on the other hand, were diverse in origin, and often had lands of their own. Although some have suggested a political motivation for Arthur’s diminished role in Chrétien’s portrayal, that lesser role may simply reflect the need to choose between the past deeds of an already powerful monarch and the present feats of his knights. An individual, riding out on his own, ready to confront whatever challenge may come his way, is the characteristic figure of romance.

Geoffrey was Welsh and spun his tale, in part, from Celtic folk stories imbued with the magic of a pagan mythology. In his History, Arthur has two hundred philosophers who read his future in the stars, and a cleric who can cure any illness through prayers. Above all, Geoffrey created the prophet and magician Merlin, centrally important to the career of King Arthur. Still, he was chary in his relation of what the French would call marvels. Chrétien proves more receptive. He gives us strange fountains, mysterious maidens bearing messages, companionable lions, hints that there exists another realm independent of our own and more powerful. This inheritance from lost Celtic tales is fragmentary in Chrétien’s romances, but becomes more pervasive in the expansive French narratives that dominate vernacular romance in the early decades of the thirteenth century.

Chrétien seems to have been reticent about what later came to be called “courtly love,” a term invented by Gaston Paris in the nineteenth century. There is a faint trace of it in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s statement connecting “the brave” and “the fair,” but it was first elaborated, from yet ill-defined sources, by the lyric poets of southern France, the twelfth-century troubadours. Fundamental, and revolutionary, in this phenomenon is the belief that a man can be ennobled through striving for a woman’s love. A corollary – assumed rather than logically necessary – is that love is incompatible with marriage, because true love must be free of social constraint. Erotic passion, in antiquity, was considered a disaster, a curse from the gods, and the warriors of early medieval French epic poems had essentially no interest in women, except as a form of property. It was a radical transformation when, at least in literature, a knight could be regarded as lacking prestige unless he won the love of a noble lady. He would devote himself to performing heroic deeds, but at least as much to a discreet courtship of his beloved, in the hope that she would consider him worthy of her favor. Occasionally he might even be granted a transcendent physical proof of her acceptance. From this we derive the homage that Western literature has paid to passionate, adulterous, and, almost inevitably, tragic love ever since the twelfth century.

The Arthurian romances of Chrétien de Troyes, however, do not reflect this trend, since they most often are concerned with finding a means to reconcile the demands of a knight’s career with his desire for a happy marriage. The exception among his romances is a story of Lancelot called The Knight of the Cart, whose plot and meaning were both provided by the poet’s patron, Marie de Champagne, granddaughter of Duke William IX of Aquitaine, the first known troubadour, and daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine. It was she, presumably, who first imagined the exemplary knight in love with King Arthur’s wife, Guenevere. Chrétien does not relate the beginning of Lancelot’s love for the queen but concentrates on a later episode in their relationship: the queen has been abducted, and Lancelot abruptly appears, already on his way to rescue her. The abduction of the queen seems to be a Celtic motif, and the hero’s name, Lancelot du Lac, may have had a Celtic source as well. Chrétien writes briefly of Lancelot’s having been raised by a fairy who gave him a magic ring, capable of distinguishing enchantments from realities. The fairy will come to help him whenever he is in need.

The cart mentioned in Chrétien’s title suggests the guiding principle of the story: the true lover must be ready to sacrifice even his honor for the sake of his beloved. In this first test of his devotion, Lancelot can only rescue the queen if he agrees to ride in a vehicle considered shameful because it was used for the transport of criminals. The knight hesitates, though only for a few seconds. When her freedom has been restored, the queen refuses to see him, outraged by this evidence of imperfection in his love. Later, he is given a chance to redeem himself during a tournament. Guenevere requests that he behave like a coward, and he does so, with no sign of distress.

The intensity of Lancelot’s love causes him almost to lose his mind; he is so lost in adoration that he notices nothing of the world around him; he is so determined to reach his beloved that he can find the strength to wrench iron bars apart; he is so moved by finding the queen’s comb, with some of her hairs caught in it, that he venerates it like a holy relic. The queen acknowledges her own passion only when she believes that Lancelot has died. The tale is filled with odd and marvelous adventures and with much that can be seen as unsympathetic caricaturing of “courtly” love. Chrétien left it to be finished by a colleague, whether from disapproval or simply loss of interest is not known. But the adulterous relationship of Lancelot and Guenevere had now found a permanent place in Arthurian legend.

The work with which we are concerned here is an anonymous series of early thirteenth-century French prose romances collectively called the Lancelot-Grail, or Arthurian Vulgate Cycle.1 It narrates in elaborate and leisurely detail the rise and fall of King Arthur, intertwining a chronicle of politics and warfare, chivalry and love with the sorcery of Merlin and the quest for the Holy Grail. It is a broadly ranging fiction, expressive of the ideals, realities and underlying questions of its time, uncomfortably caught between a Christian imperative and the vibrant memory of a pagan past. Of the five romances – The History of the Holy Grail, The Story of Merlin, Lancelot, The Quest for the Holy Grail, The Death of King Arthur – Lancelot is by far the longest and most luxuriantly filled with character and incident. The story of Lancelot and the queen is fully developed here and in the fifth romance, where it will reach its unhappy end, along with the downfall of the kingdom.

Many motifs connect The Knight of the Cart with the Prose Lancelot, among them the hero’s discovery of his eventual tomb, and the extreme deference that he shows to the queen, but the spirit of the prose work is entirely different. Two factors are particularly important: magic and a new understanding of love.

The helpful fairy mentioned by Chrétien has now become the Lady of the Lake. Named Niniane, or Viviane, she has a prior history connected with that of Merlin, who attempted to seduce her. Knowing that Merlin’s father was a devil, she only pretended to accept him, trading illusory favors for his knowledge of sorcery. In the end, she has learned enough to confine the magician in an invisible tomb from which he will never emerge. Among the gifts she has learned from Merlin is an ability to foretell the future.

Thus it can be assumed that when the Lady of the Lake carries off the infant Lancelot, to raise him in her magical kingdom concealed by the semblance of a lake, she does so as an agent of his fate. He grows up believing her to be his mother, and even after he has apparently been released from her influence and fallen in love with the queen, the Lady of the Lake still shapes his life. In times of danger she sends him magical weapons, she heals him when a fit of madness has brought him close to death, and she encourages Guenevere in her illicit love. She is not deterred by her foreknowledge that that love will ultimately destroy the Arthurian kingdom. On the contrary, it would seem that she has extended her hatred of Merlin to include his protégé King Arthur, born thanks to Merlin’s sorcery. In our retelling of the story, the final gesture of her own magic is to slip Excalibur, which has been Arthur’s sword, into Lancelot’s tomb.

Lancelot lives in exile from a land he has never known, from a royal birthright he has never made an effort to recover. His real homeland is the Lady’s domain, and it seems indeed to be real in every way. But it is an otherworldly, enchanted place, and no one who meets him in later life can fail to find him correspondingly extra-ordinary. His exceptional beauty is always mentioned – and beauty, in medieval times as well as today, was regarded as a sign of a person’s moral worth. There is a radiance about Lancelot as a child, and a physical ease, so that everything comes naturally to him, whether it be reading or riding fine horses or jousting. The intensity of emotion that will characterize him as an adult is shown, in his early years, by his response to perceived injustice. When the Lady, for a moment, seems somewhat remote, he is ready to gallop away in the direction of King Arthur. He does not notice that she is in distress, having realized that her cherished ward has reached the age when he must leave her and become a knight. Later on, he will not always notice the grief of others.

A certain insensitivity is useful in a hero. Lancelot, when he fights, is more a force of nature than a man. He is impersonal also in his ignorance of his past, of his lineage. The Lady, bidding him farewell at Arthur’s court, reveals that she is not his mother, but tells him little more about his identity. In the white armor she had given him, he goes out alone into the world looking for trials of his prowess. The greatest of these is his conquest of Dolorous Guard, a victory not only over forces that had defeated many famous knights, but also over the supernatural. In the aftermath, he discovers not only the tomb where he will be buried but also learns his very name, and that he is the son of King Ban. The discovery is to remain his secret, however, until much later.

Perhaps this revelation seems to him merely abstract. Or perhaps he feels unworthy of such a heritage, despite his extraordinary accomplishments. The Prose Lancelot offers no speculations. What is clear is that when he turns once again toward King Arthur’s court, the White Knight, who might be recognized, takes on a new persona as the Red Knight, whose valiant performance on the battlefield will be surpassed on a subsequent occasion by the even more impressive Black Knight. No one imagines a connection between the Lady’s beautiful youth dressed in white and this warrior on whom King Arthur’s very survival has come to depend.

Before Lancelot’s return, King Arthur was challenged by Galehaut, Lord of the Distant Isles, a realm almost as mysterious as the domain where Lancelot had spent his childhood. Galehaut’s mother, we are told, was a giantess, and we learn, from another thirteenth-century source, that his father imposed such cruel customs on visitors as to make his son prefer a life of exile. Galehaut’s ambition was nothing less than conquest of the world, and so far he had known nothing but success. By the time he sent his challenge to Arthur, he had conquered twenty-eight kingdoms, whose rulers, recognizing his inherent nobility, had then become his devoted allies.

Such was Galehaut’s sense of personal honor that he broke off his first engagement with King Arthur, whose forces were so weak that he seemed an unworthy opponent. That they had not been immediately overthrown was due solely to the presence of a stranger, identified only as the Red Knight. Arthur was given a truce to increase the strength of his army, but the Red Knight had disappeared. Without him, there seemed to be no hope of defeating Galehaut. When the fighting resumed, a year later, both armies were larger than before. Again an unknown knight, this time in black armor, fought for Arthur, and prevented a total rout on the first day. This time he had the assistance of Galehaut himself.

The Lord of the Distant Isles had seen countless great warriors in battle, but in Lancelot he witnessed something completely unprecedented. Men of both armies had described him as “winning the war all by himself.” Now the last of Lancelot’s horses had been killed under him, and he stood “like a battle flag on the field,” surrounded by dead and wounded knights, yet seeming himself invincible; those who would have attacked him, alone and on foot as he was, drew back. The sight, for Galehaut, had the force of a revelation. The whole course of his life turned around at that moment; no kingdom, he thought, would be worth the death of such a knight.

Lancelot, being mortal, might well have died that day, had Galehaut not supplied him with horses and ordered his men not to attack when the knight was on foot. We do not know what Galehaut intended by inviting Lancelot to his camp after the battle, but presumably it had to do with his desire to give expression to his admiration. He might have wondered how closely the Black Knight was attached to King Arthur. We also do not know the nature of Galehaut’s reaction when he discovered that the valiant helmeted warrior, once disarmed, was also a paragon of manly beauty. What is certain, however, is that he did not hesitate to grant Lancelot’s wish that he surrender to Arthur; moreover, he would have done so immediately, without staging a dramatic renunciation of victory only after having proven his might in battle. But any plan desired by Lancelot was a plan that Galehaut was prepared to execute, and Lancelot wanted King Arthur not only saved from defeat but saved through his intervention. Henceforth, Arthur would owe his realm to the Black Knight. And Galehaut would have yielded all the grand ambitions of his life in exchange for having Lancelot as his companion.

To Guenevere the young knight responded as both fearless warrior and timid lover. She, however, perceived nothing of either. Seeing the disguised black-armored defender, she would scarcely have remembered the youth dressed in white whom she once dismissed with a kind but meaningless word; and later she was more amused than impressed on learning that, when Lancelot conquered Dolorous Guard, and then held back the huge armies of Galehaut, the memory of that word loomed large as his inspiration. A simple mistake! She can hardly be faulted for being what she was: a queen, experienced in the world, perhaps disenchanted, the most beautiful of women, of whom it was said she ennobled all who came into her presence. If the king had loved her once, little of that was left but ceremony, and now affairs of the heart seemed to her an inconsequential game. Thus, having accepted Lancelot’s love in the tale’s remarkable scene of avowal, she could assign the Lady of Malehaut to his friend, simply to make a foursome, and to have a confidante. Fear and sorrow would eventually change her, but, almost always, she would let herself be ruled by expediency.

If King Arthur could be said to do the same, it was in his instinctive refusal to perceive Lancelot as a threat to his marriage. No doubt he relied on Lancelot too much: Lancelot the greatest warrior in the world, Lancelot who made the peace with Galehaut, Lancelot who could defend his realm from endless threats of invasion. Arthur only thought to draw him closer to his court, to keep him there as a knight of the Round Table. One could say that he was credulous, or, convinced of his own greatness, could not imagine a rival for the queen’s love. He himself, however, was easily and frequently seduced. He was also given to hasty, and damaging, decisions. When he had a last chance to save his kingdom, he lost it out of pride, or perhaps out of dignity. There was dignity, at least, in his final moments, and ambiguity as well. Whether the king has foreseen it or not, the hand that rises from the lake to seize his sword Excalibur will place it in Lancelot’s grave, suggesting that the weapon always identified with Arthur more truly belongs to the younger warrior. Arthur himself is borne away by his half-sister Morgan. Her appearance at this point is darkly disturbing, for she has been, throughout the romance, an agent of evil, attempting to use Lancelot in order to destroy the queen. Now she takes possession of Arthur, who goes with her willingly; his mortal wounds will perhaps be healed in Avalon. Whatever we may think of this alliance, it could hardly surprise the Lady of the Lake. For her it can only be a final justification of her enmity.

The trajectory of the fictional King Arthur reproduces that of the early Britons when the chaos of Saxon invasions gave way to a time of peace and confidence, only to be reduced to chaos again, and finally defeat. When Uther Pendragon, Arthur’s father, died, his son was too young to dominate the kingdom. The barons fought for the kingship, and there was no safety for anyone, anywhere. With Merlin’s help, Arthur prevailed. The kingdom was powerful, its borders secure, and King Arthur’s court became a source of reliable justice.

At the time of our story, this is no longer true. Lancelot provides a kind of last hope, a vision of a knight as knights were imagined to be. But he alone cannot defend the realm against an enemy as powerful as Galehaut. And Galehaut, deflected from his conquest by his love of Lancelot, then spurred by that very love to satisfy Lancelot’s yearning for the queen, makes possible the adultery that will eventually destroy the court of Arthur from within.

After King Arthur, as the Lady of Malehaut says in the end to Guenevere, the kingdom is even worse off than it was when Uther died, since Arthur leaves neither son nor heir. Excalibur lies magically in the grave with Lancelot, the grave he shares with Galehaut, and of all the participants in the drama, only one, the Lady of the Lake, remains undiminished.

The story of Lancelot and Guenevere has, since the twelfth century, been part of every significant account of King Arthur. The second, overlapping, love story related in the Prose Lancelot, in which Galehaut, Lord of the Distant Isles, sacrificed his power, his happiness, and ultimately his life for the sake of Lancelot, has been wholly forgotten.

Lancelot is the book that Paolo and Francesca have been reading in the fifth canto of the Inferno when they yield to their love. Dante mentions Galehaut in passing as the intermediary between Lancelot and the queen, and Boccaccio, moved by the great lord’s generosity, uses his name as the subtitle of his Decameron (“Il Principe Galeotto”). But in later imaginings of the Arthurian saga itself, Galehaut, for all his prominence in the original narrative, was rapidly marginalized and even eclipsed. The greatest retelling in English, the fifteenth-century work of Thomas Malory, reduced the character to one of no significance, leaving Guenevere without a rival for Lancelot’s affections, and subsequent novels, plays, poems – now films as well – have accepted that simplification of the tale. Indeed, so obscure has Galehaut become that modern readers sometimes take the name to be a mere variant of Galahad – a gross mistake. Galahad is the “pure,” the “chosen,” knight who achieves the quest for the Holy Grail in a part of the Arthurian legend quite distinct from the story that concerns us here. There is no connection between the two figures.

What accounts for the fate of Galehaut since the Middle Ages is not at all clear, though one may certainly suspect political embarrassment: the character is, after all, King Arthur’s outstanding adversary and would have defeated him easily, had he not fallen in love with Lancelot. Moral disapproval may also explain it, since the Old French text is wholly sympathetic to the homoerotic relationship. Certainly, in the case of Malory, various factors may be adduced, including the writer’s general inclination to concentrate on tales of chivalry rather than love, treating love with a prudish aversion not characteristic of the French romance; and his readiness to draw from several sources – not only the Prose Lancelot – with a consequent de-centering of Lancelot by the inceasingly salient figure of Tristan. Moreover, Malory was surely aware of the need for caution in handling conflicts and alliances that might too readily be taken to reflect, perhaps with dangerous partiality, the troubled state of Britain in the latter half of the fifteenth century. Galehaut, powerful and ambitious, taking aim at Arthur’s England from a region readily perceived as Wales, would too strongly have suggested contemporary tensions between the Crown and its Welsh adversaries for the writer not to fear charges of supporting the wrong side. Nor could Malory ignore the perils of seeing his narrative interpreted in the light of the ongoing dynastic struggles between Lancastrians and Yorkists, the so-called Wars of the Roses.

Whatever the cause of Galehaut’s fading, it was obvious to us that the character deserved to be rescued from oblivion – or, for some, from the opprobrium attached, wrongly, to his action in bringing Lancelot and Guenevere together. Ours has been a work of restoration. The masses of detail and the labyrinthine complications of the original obscure, for modern readers, the great double love-story which we have tried to bring to light. To the best of our knowledge, in all the broad corpus of modern fiction derived from the Arthurian legend no such attempt has hitherto been made. Isolating the major strands of Lancelot and, to a lesser extent, The Death of King Arthur, we have rewoven them into a spare recounting for our time. Such treatment has the further advantage of making apparent the central irony of the plot: Lancelot proved indispensable to King Arthur but also became the instrument by which the Arthurian kingdom was destroyed. Without Galehaut’s solicitude, the fateful adultery would not have occurred.

Like the original, our retelling concentrates on character and incident, with little concern for the explicit depiction of milieu common in modern novels. Description of persons and places remains minimal and suggestive, just as the flow of time is noted without consistent precision. In the same spirit, we have often presented dialogue bare of comment or, as happens frequently in the medieval text, in fragments emerging directly from the narrator’s prose. We have, of course, preserved the supernatural elements as integral parts of the tale and so inherent to its universe that they appear continuous with the natural. In our retelling, as in its source, there are thus crucially important otherworldly beings and dwellings, enchantments and magical events, and fabulous enhancements of reality. These may even be said to shape the story.

We have preserved, as well, characteristic modes of behavior that may be unfamiliar to modern readers, whose understanding of chivalry tends to emphasize its idealistic aspects. When people today think of the strong protecting the weak, or the transformation of warfare by the imposition of rules – such as the obligation to show mercy to an opponent who surrenders, or the equation of true nobility with generosity and refinement of manners – they tend to forget that knights live as warriors in a context of violence. Knights are always in a state of readiness for battle, and scarcely know what to do in a time of peace; thus Galehaut’s men regret the imposition of a truce, and Lancelot, on Galehaut’s isolated island, complains that they are wasting their time. In the intensity of warfare they find their truest way of being, and it leads to a kind of forthrightness in the expression of emotion. Warriors in epic poems, as well as in the literature of romance, readily shed tears, and even faint. But modern athletes, too, may have tears in their eyes, whether at moments of victory or defeat.

Another aspect of epic poetry preserved in chivalric romance is the theme of male companionship. Like Achilles and Patroclus in the Iliad, Roland and Oliver in The Song of Roland know nothing of the courtly idea that a man can be ennobled by devotion to a woman. Galehaut and Lancelot would have been just like them, had it not been for Guenevere. Indeed, an important aspect of our story is its playing out of the conflict between that ancient warrior tradition and the emergence of a new, competing ethos. It should be noted in passing that, whatever else in the narrative may give evidence of homoeroticism in the relationship of Lancelot and Galehaut, the sharing of a bed does not by itself point in that direction, for such sharing, by men or by women, seems to have been common enough in the Middle Ages as an expression of friendship (or practicality) with no erotic overtones.

It may be useful to point out as well a central trait of the feudal society depicted in our book: it was a polity held together by bonds of reciprocal obligation. Lancelot’s first adventure after becoming a knight offers an example. If the Lady of Nohaut calls upon King Arthur for protection, it is because he is her “liege lord.” She, as his “vassal,” “holds” her “fief” from him, meaning either that he gave her title to her land in return for economic and/or military service, or that she pledged such service from her estate in return for royal protection. In either case, if her own people cannot defend Nohaut against invaders, it is the king’s duty to provide the defense – which here takes the form of Lancelot’s engagement as her champion. It will be in essence a trial by combat, and it will be but the first in Lancelot’s career.

In such confrontations, it is understood that, however uneven the contending forces may be, God will guide the right side to victory. This was an integral part of the medieval judicial system, a way of resolving disputes when an accused person had no clear proof of innocence. The practice was not infrequently used to settle even disputes concerning Church property, although it was periodically condemned by conservative clerics. A well-ordered appeal to divine judgment clearly marked an advance over undisciplined violence or the arbitrary imposition of seigniorial power. Trials presided over by a disinterested human judge and subject to the deliberations of a jury were not yet the norm at the time of our story. And the possible contradiction between an apparently God-sanctioned combat and a Christian doctrine opposed to fighting seems not to have troubled too many people. In literary works, a trial by combat frequently entails such an imbalance of contending forces that the protagonist’s victory will appear inexplicable if not for the beneficent will of God. In the trial at Nohaut, Lancelot is young and inexperienced, his opponent a formidable warrior. Later on, when he fights for Guenevere, Lancelot will insist on facing three opponents at once.

Unlike our Old French source, we have stripped the legend of everything not closely related to the development of Lancelot’s affective life and the role of Galehaut in that evolution. Thus, various subplots and missions involving one or another knight of the Round Table have been omitted, including some exciting magical adventures and, most notably, all traces of the quest for the Holy Grail (an episode that occurs after Galehaut’s death). We have eliminated a host of characters, reduced the presence of others, and even reshaped the trajectories of a few.

All changes have been made in the interest of tightening the story without distorting the fundamentals of the original narrative. In any case, it was our intention, not to prepare either a translation or an abridgment of the Old French source, but to retell the central love-drama in such a way as to restore its complexity and emotional depth for the modern reader.