Читать книгу The Movement for Reproductive Justice - Patricia Zavella - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

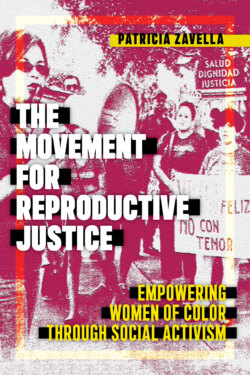

Voicing Our Power: Soy Poderosa

ОглавлениеAs part of the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health’s strategic culture shift work, the organization has conducted a “soy poderosa and my voice matters” campaign for several years, highlighting it annually during early August. NLIRH defines its strengths-based approach this way: “A civic engagement campaign created to engage, organize, and lift the voices of the Latina community, regardless of immigration status and ability to vote, as we continue to mobilize a broad constituency in support of reproductive justice and work across movements to create sustainable change.”43 Diverse participants take their photos with a sign that says, “soy poderosa and my voice matters” and “I am powerful because”—and they fill in the blanks: “because I’m a human being,” “porque soy feminista [because I’m a feminist],” “porque tengo una voz [because I have a voice],” and so on. The images of those who claim “soy poderosa” include women and men of diverse racial-ethnic backgrounds: Latinas, African Americans, and whites.

When NLIRH posts photographs of demonstrations or other events on social media where demonstrators are wearing tee-shirts with the organization’s logo, often its supporters include young Latino men. These images disrupt our expectations about race and gender by having those who are not Latina post “soy poderosa” and leads this viewer at least to reflect on how and why those who are not Latinas post these photos. Are the women who appear to be Black or white actually Latinas? Does the man who appears white and posted “soy poderosa porque soy feminista” (I am a powerful woman because I’m a feminist) claim a feminine identity? Are those who are not Latina expressing their solidarity with NLIRH? I asked executive director Jessica González-Rojas about the diversity of participants represented in the organization’s “soy poderosa” campaign. She smiled as she recalled, “For us it was about demonstrating support and being an ally to us. ‘Soy poderosa’ is a Latina claim, but it’s part of our philosophy and values with a ton of alliances and collaboration and publishing work. So, engaging our partners in saying ‘soy poderosa’ was important.” The “soy poderosa and my voice matters” campaign also illustrates intersectionality, according to González-Rojas: “Online women will say, ‘I’m queer and I’m an activist and I’m an immigrant,’ and like whoa, intersectionality! We try to really create the space to allow people to bring their whole selves to the movement. So that was really important.” I asked a young man in South Texas how he felt wearing a “soy poderosa” tee-shirt, and he smiled and then shrugged and explained that the gender-bending language did not bother him because he was interested in supporting women.

The idea of “soy poderosa” came out of a survey that NLIRH conducted with the Reproductive Health and Technology Project on Latinxs’ views on abortion. The organizations administered the survey to six hundred Latinx registered voters in twenty-five states, and half of the respondents used the Spanish version. The survey generated unexpected findings since the pollsters knew that the majority of Latinxs are Catholics and that the Catholic Church condemns abortion.44 However, 68 percent of the survey participants agreed with the statement “Even though Church leaders take a position against abortion, when it comes to the law, I believe it should remain legal.” Furthermore, 74 percent of the respondents agreed with the statement “A woman has a right to make her own personal, private decisions about abortion without politicians interfering.”45 Eighty-one percent agree that abortions should be covered by private or state-funded health insurance.46 González-Rojas explained the significance of these findings: “From that poll we learned that you can’t ask that four-way question; there’s a standard way for asking: ‘Do you think abortion should be legal all the time, legal most of the time, illegal sometimes, illegal always?’ You’ll get the ‘illegal most of the time’ when Latinos are asked that question that way. But when you say, ‘No matter how you feel about the procedure, do you think women should make the decision for themselves?’ You’ll get like 70 percent of Latinos agree. So it’s about language and framing.” Later she emphasized that the survey was “a game changer”: “The results were very complicated though and nuanced. And then about half the respondents were in Spanish, so it wasn’t translated literally; it was ‘what’s the essence of the question?’ and capturing that essence in Spanish, so it was a ‘transcreation.’” As NLIRH researchers were analyzing the survey data, they categorized the respondents and began calling those in the category of being engaged and vocal as “las poderosas” and developed the campaign. González-Rojas stated, “We envision ‘soy poderosa’ as a civic engagement strategy: say, ‘I am powerful and I vote. I am powerful and I support health care. I am powerful and I x, y, z.’ So, the primary objective was to lift up our community by showing partners in cross-movement collaboration.”

This research about abortion was instrumental in helping Young Women United and Strong Families New Mexico to lead the effort to defeat the proposed municipal ban on abortion in Albuquerque in 2013.47 California Latinas for Reproductive Justice conducted similar research on abortion with 898 respondents. According to Ena Suseth Valladares, CLRJ’s director of research: “We wanted to know what Latinos really think about abortion. We wanted to move away from the whole pro-choice/pro-life stance: Should it be restricted? Should it not be restricted? We wanted to ask in a completely different way, because the way that we understood it and the way that people talked about it was that it was a lot more complicated than just categorizing it as an either/or label. Also, we felt that pro-choice/pro-life was not something that was really translatable. I mean in Spanish what do you say?” CLRJ commissioned its survey with a research firm recommended by NLIRH and also had unexpected findings, according to Valladares: “We found that participants strongly believe that abortion should be an option for women; that tested really well. We also found that participants agreed that the information shouldn’t be shaming or trying to change women’s minds, so that was very heartening. We also found that over eight in ten participants strongly agree that every woman should have a right to decide for herself the number and spacing of her children.” CLRJ uses these findings in its reproductive justice workshops and position papers.48

NLIRH sponsors Latina Advocacy Networks in Florida, New York, Texas, and Virginia with low-income Latinas, many of whom have limited opportunities for schooling. I witnessed how the organization promotes “soy poderosa” discourse during its leadership training in Texas. It makes the community meetings and trainings attractive and fun by offering food, playing games and holding raffles in which women win household items or notebooks, and playing popular music and showing film clips with political messages. Women who attend regularly receive a shirt that says “soy poderosa” on the front in royal blue and yellow colors with NLIRH’s logo. When I was gifted one of the shirts, I felt welcomed into the fold. In addition, they normalize poderosa discourse when welcoming participants or asking how they are feeling; the response is always, “¡Poderosa!” When playing bingo, the winner yells out “poderosa” to signal that she has won. Women seem to delight in proclaiming that they are powerful, and several disclosed that coming to embrace their poderosa identity was a major departure from their previous experience. During the Leadership Training Institute, for example, Maria Bustamante felt compelled to share the reflections she wrote after learning about systemic causes of social problems: “As we empower ourselves through consciousness, we prepare ourselves with value and without fear. We continue the struggle, opening roads and transforming lives. In this great country that is formed by emigrants, we are part of this society. And we want the same rights to liberty and justice.”

González-Rojas reflects on the overall importance of culture shift work: “I think that is the essence of power, knowing that you have a voice and you can use that voice in ways that could create change. Power is the use of your bodily tools, your autonomy, to be able to effect change in society and break down the structural barriers that prevent our community from being healthy.”