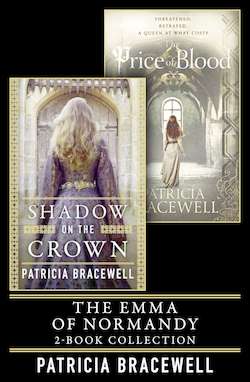

Читать книгу The Emma of Normandy 2-book Collection: Shadow on the Crown and The Price of Blood - Patricia Bracewell - Страница 27

August 1002 Winchester, Hampshire

ОглавлениеÆthelred stood beside a light-filled window embrasure in his private chamber and greeted the arrival of his eldest son with a grunt. He half anticipated another outburst of resentment like the one he had had to endure before he’d banished the pup to St Albans, and he did not relish the prospect.

Christ, he was weary of it all – the restless, sleep-troubled nights, the days of wrangling with councillors and churchmen, and underneath it all the incessant rumour of trouble that he knew was far more than rumour. He had dispatched this recalcitrant son of his to gather information, and now, eyeing Athelstan as he bent the knee with sober regard, Æthelred took heart. Perhaps the whelp was beginning to learn humility. Perhaps he would be of some use after all.

‘You followed my instructions?’ Æthelred asked, coiling himself into his chair and gesturing for his son to stand.

‘Yes, my lord.’

‘And do you understand the problem that I face?’

Athelstan inclined his head. ‘Some years ago you forged an alliance with Viking raiders who were ravaging our lands, you bade them serve you as mercenaries, and rewarded them with gold and properties. Now you have bands of well-trained, well-armed Vikings, most of them Danes, settled throughout your kingdom.’

Æthelred scowled. His son had grasped the situation well enough, if not the policy behind it.

‘I had little choice at the time,’ he said, ‘nor am I the first ruler to settle mercenaries in his realm. The Frankish king did it. Even the great Alfred was forced to allow Danes to settle north of the River Humber.’

‘But in Alfred’s time,’ his son said, his expression carefully bland, ‘the Danes settled in lands where few of Alfred’s people dwelt. Your mercenaries are in Devonshire, Hampshire, and Oxfordshire – in the very heart of your kingdom.’

His son did not say it, but Æthelred heard the unspoken accusation. He had placed a pack of wolves in the sheepfold.

‘I gave them estates,’ he growled, ‘and they gave their oaths that they would not turn against me.’

Yet they had done so, and with a vengeance. After several years of abiding by the pledges they had made to him, the dogs of war had been loosed upon England.

Æthelred, remembering, grimaced, and rubbed at a suddenly painful temple with his fingertips.

One of those dogs, Pallig, was wed to the half sister of Swein Forkbeard, and when Forkbeard had attacked the southern coast last year, Pallig and his men had joined in the assault. They had pillaged and burned all across Wessex, and the English host that rallied against them had failed to stop them.

He’d had no choice but to bribe the lot of them yet again to leave his realm in peace. Forkbeard had taken his gold to his ships and sailed east, but Pallig had merely made new pledges of peace and retreated to his estates. He and others like him were like boils upon the land that would, one day, erupt to plague him once more. He could not trust them.

‘You spoke to Pallig?’ he asked.

‘I spoke with Pallig and with his wife, Gunhild.’

‘Think you he will keep his oaths to me?’ He watched his son closely and spotted the hesitation before the answer was given. So the lad, too, saw the threat.

‘My lord,’ Athelstan said, ‘Pallig is no farmer. He is a mercenary down to his soul – an adventurer who thrives on danger and excitement. If you do not put him to some use, he will make more mischief in spite of his pledges to you.’

Æthelred waved the suggestion away.

‘Once before I set the fox to guarding the chickens and I paid the price. I will not make that mistake again. Pallig may be living on estates that I granted him, but he is Swein’s man at heart. He is like a knife at my throat.’

‘No, my lord,’ his son objected. Æthelred glared at his presumption but let him have his say. ‘Pallig is more like a kingdom unto himself,’ Athelstan went on, ‘not bound to any man. He takes whatever he feels is his by right and by force of arms. It is not the having that he loves, it is the getting. If you could but find a way to bend him to your will—’

‘Men like Pallig do not bend!’ he snarled. ‘Best you learn that now, boy. If money will not sway him, nothing will.’ Good Christ, he had dealt with vermin like Pallig for two decades; he knew them far better than this cub of his, who had not yet seen eighteen summers.

Athelstan frowned at his father, sympathy for the king’s dilemma warring with exasperation. That England was beset by enemies from within as well as from without was the king’s own doing. Granted, the marriage to Emma might stem the tide of Viking raids, but Æthelred had made a devil’s bargain when he had given land to men like Pallig. They were like feral dogs that must be tamed and muzzled. He could think of only one way to do it.

‘Pallig has a son, my lord,’ he said urgently, ‘newly born. Take the boy as hostage for his father’s good behaviour.’ If the boy were raised at court, he would become English and no Dane. Build trust with one child, and others, no doubt, would follow.

‘Hostage?’ Æthelred almost spat the word. ‘It is far too late for that now. We might have made it a condition in March, before we made the gafol payment, but now we have nothing with which to bargain. Pallig will not willingly hand his son over to me.’ He fingered his beard, his face brooding and dark. ‘He is safe on his own lands, surrounded by his warriors, a law unto himself. Nor is he the only one. There are a dozen more like him, spread across the southern shires. Who is to say what schemes they may be plotting?’

Listening to his father’s groundless suspicions, Athelstan’s exasperation finally overcame his sympathy.

‘Who is to say that they are plotting any schemes at all?’ he demanded. ‘What if they are not? What if Pallig merely craves action? He is a shipman! Can you not put together a fleet and charge him with guarding our coast? My lord, what other choice have you?’

His father made no answer, and Athelstan, looking into a face that he suddenly realized was haggard and far too pale, felt a sudden chill along his spine, as if a blade had been drawn through ice and laid against his skin. The king was staring, red-rimmed eyes fixed and frightened, at something behind Athelstan. He whipped around, fearing to see some horror there, yet he saw nothing save a bank of candles whose meagre flames trembled in a shadowy corner, where the daylight did not reach.

He turned back to the king, and still his father stared, his face working as he mouthed a soundless cry, knuckles whitening as he clutched the carved dragon heads beneath his hands.

‘My lord!’ Athelstan cried. Was this some fever of the mind sprung from the cares that beset a king? Some disease that struck suddenly and left nothing but the shell of a man in its wake?

He reached out and clasped his father’s hand, and he was stunned by how cold the taut flesh felt beneath his palm. His own blood seemed to freeze in response, and he felt suddenly afraid that he was watching his father die.

He grasped the king’s shoulders and shook him, not knowing what else to do. In response the watery blue eyes came to rest upon his own, but the king’s distress seemed to become even more acute. His father bent forward, his body rigid as he beat his breast and moaned a wordless cry, tortured by some invisible enemy.

‘My lord!’ Athelstan cried again, raging at his helplessness. Why did no one hear him, no one come to offer aid?

Yet even as he formed that thought, his father’s body relaxed, and the bent head dropped into the king’s slender hands. Athelstan’s panic eased, and he felt as if he had just wakened from a nightmare.

Slowly his father raised his head, and now his face was creased and grey as the wide eyes fixed purposefully on Athelstan.

‘What did you see?’ the king demanded in a hoarse, urgent whisper.

Athelstan hesitated, unnerved by the intensity of his father’s gaze, his mind groping desperately for a response that would appease the king.

‘I saw shadows, my lord,’ he replied at last. ‘Only shadows.’ And I saw a king half mad with fear, he thought. But of that he dared not speak.

His father drew a long breath and released it as he repeated Athelstan’s response.

‘Only shadows,’ he whispered, and he pressed his hands against his eyes, as if he would banish whatever baleful vision lingered there.

Athelstan roused himself to fetch wine from the nearby table that held cups and a flagon. He watched while his father drank, and a hundred questions formed in his mind.

‘Were you in pain?’ he asked. ‘Has this’ – he searched for some way to describe it – ‘affliction struck before?’

His father, much revived, it appeared, by the wine, threw him a dark, almost furtive glance.

‘It was but weariness, nothing more,’ he murmured. ‘It has passed now. There are far weightier matters to occupy both my mind and yours. You will forget it.’ He left his chair and began to pace, restless and distracted. ‘There have been signs,’ he said heavily, ‘of trouble to come. I have seen portents—’ He flung up an arm as if to sweep away his own words. ‘Nay, I need no portents to know that Pallig is dangerous. As you say, he is no farmer. Neither are the men who answer to him. They will become restless, and then they will strike.’

The next moment the chamber door opened, and his father’s steward, Hubert, entered carrying a packet of documents. The king raised a hand to forestall whatever Hubert might say and looked gravely at Athelstan.

‘Did you see any indications that Pallig was preparing for battle?’

‘No, my lord,’ he said, mystified both by what he had just witnessed as well as by his father’s apparent determination to ignore it.

The king grimaced, as if that was not the answer he had anticipated. ‘Then there is nothing more to do, for now.’ He brushed past Athelstan as he made for his chair and beckoned to the steward. ‘Leave me. I have business with Hubert.’

Athelstan stood there for a moment, troubled, unwilling to leave before he had gained a better understanding of what he had just seen. But both men ignored him, and he knew better than to disobey his father’s command. He strode slowly from the chamber and, glancing back, he saw his father’s eyes now fixed hard upon him, and in those eyes was a warning that it would be perilous for him to ignore.

As he made his way through the great hall, something that Bishop Ælfheah had said to him in the spring came back to him: The king is troubled in his mind. Had the bishop been witness to a similar occurrence, then? Ælfheah had not explained himself, and Athelstan dared not question him about it now. That threatening glance from his father had commanded his silence. He stepped from the royal apartments into the sunshine of late summer, his mind still wrestling with the king’s strange behaviour and his talk of signs and portents.

Yet he, too, had been given a sign by the seeress near Saltford – albeit one he was unwilling to believe. And last winter there had been rumours from the north that men had seen columns of light shimmering in the night sky – fierce angels with swords, it was said, come to punish men for their sins.

Truth to tell, his father was not the only one disturbed by such portents, yet what steps could anyone take to vanquish foreboding or to prevent some cataclysm that was lurking in the future? And then, recalling his interview with the king, he knew with certainty that his father must be planning steps of some kind. Why else had he been sent to speak with Pallig? Yet if his father did have some presentiment of disaster might not his very efforts to avert it bring about the misfortune that he so dreaded?

Try as he might, Athelstan could not penetrate the mysterious workings of the king’s mind any more than he could unravel the dark threads of the future spun for him by the cunning woman beside the standing stones. It was a futile endeavour, and when he heard the shouts of children’s laughter, he willingly relegated his father’s troubling words and actions to the back of his mind. He had forgotten that the children would have returned to Winchester, and he followed the sound of laughter into the queen’s garden. There, the sight of his brothers and sisters playing at dodge the ball seemed innocent and blessedly carefree. He was astonished, though, to see that the queen had joined them in their game. It was not something that their own mother had ever done.

He glanced around the garden, noting the absence of any of the English noblewomen who should have attended the queen. So the rumours that had reached him at Headington were true. There were two courts at Winchester, one made up of the king’s retinue, the other of Emma’s mostly Norman entourage. That, he guessed, was the result of his father’s dissatisfaction with his bride. The king had expected to wed a child who would speak only Norman French, and so could be kept ignorant of the currents of information swirling around the hall and the palace – information that she might impart to her brother and, through him, to the king’s Danish enemies. Emma’s skill at English had astonished them all and must have infuriated his father.

But if the queen could be a conduit for information going from England to Normandy, and thus to Denmark, then she could be a conduit in the other direction as well. His father, so focused on Pallig and the enemies he perceived within his borders, had probably made no effort to learn anything from Emma about Duke Richard – about his ambitions or his allies. But someone ought to do it, and soon – before the king’s misguided animosity towards his bride made her despise all of them.

Emma scooped up the leather ball, took aim at Edgar, and threw, but the lithe nine-year-old easily dodged her poorly aimed missile.

His brother Edward taunted her cheerfully from his position next to her in the circle. ‘You throw like a girl.’

Emma laughed. ‘I did not have any brothers to teach me how to throw.’

‘But you have a brother, do you not?’ Edward asked, deftly using his foot to stop the ball that skipped towards him. ‘Is he not the king of Normandy?’ He hurled the ball at Edgar, but he, too, missed.

‘He is the duke,’ Emma corrected him. ‘Normandy is a part of France, and so my brother’s overlord is France’s king.’ Not that her brother ever took much notice of the opinions of the French king. ‘But my brother, like your father, rules a great land filled with many people, very much like a king. He is much older than I am, though. When I was a girl he was already a grown man and had no time to teach me to throw a ball. I am very good on a horse,’ she said, hoping to impress Edward, who was regarding her sceptically. ‘I learned to ride when I was quite, quite small,’ she said, catching the ball that Wymarc, in the centre of the circle, had nimbly sidestepped.

‘Then we must go riding this afternoon,’ Edward urged, his face lighting with enthusiasm. ‘It is much better than playing with a ball.’

Emma frowned, wondering if she should attempt it. She longed to ride, but every time she had even approached the stables here, which lay just outside the palace compound, her guards had turned her aside. They were courteous enough, but they had their orders, and she could guess what they were. The queen must not be allowed outside the palisade – for her own safety, of course.

If she attempted to visit the stables with Æthelred’s children and was turned away, they would quickly realize that she was a prisoner, and from that deduce that she was an enemy. The bonds between them – so fragile, so carefully forged during their time together in Canterbury – would melt like ice in the sun.

‘Perhaps we can go tomorrow,’ she hedged, ‘if the weather remains fine.’ She would have to try, once again, to speak to the king. If she were in the company of the children, their attendants, and a score of guards, perhaps he would let her go.

She reached to her left to catch the ball that the boys’ tutor had hurled from the other side of the circle, but it bounced against her hand and went off at an angle. Emma turned to retrieve it but drew up abruptly at the sight of the young man who captured the ball with easy grace.

‘My lord,’ she said, unsettled by the steady gaze of Æthelred’s eldest son.

‘I advise you to take advantage of the sunshine, my lady,’ he said. ‘You cannot count on fine weather for the morrow. I, for one, wish to try one of the excellent mounts that accompanied you from Normandy.’ He tossed the ball to his brother. ‘What do you say, Edward? Shall we take the queen for a ride?’

‘Yes!’ Edward said, the ball game forgotten. ‘Edgar must come, too. We do not have to bring the girls.’ His tone became suddenly imperious. ‘They are too little. They would only slow us down.’

He smirked at his sister Edyth, who wrinkled her nose at him and stuck out her tongue.

‘We don’t like horses, anyway,’ she said. ‘They smell. And boys smell even worse. We’re going to play with the kittens.’

She marched off to her nurse, nose decidedly out of joint, her sister Ælfgifu in tow. It appeared that the ball game was over.

Emma turned back to Athelstan, who, with a quick jerk of his head, sent his two younger brothers pelting for the stables. The sun lit his tawny hair with golden highlights, but that was the only thing warm about him. He did not smile, merely waited politely for her reply.

She did not know what to make of him, or of his invitation.

‘The guards,’ she said, hesitating, ‘will not allow me to—’

‘I will take responsibility for your safety,’ he said.

She understood then. She would still be a prisoner, escorted by the ætheling and his men rather than her Norman hearth troops. Nevertheless, she would be outside the city walls for a time, on her own mount, in the sun and the gentle summer air. It might not be freedom, but it was as close as she was likely to get.

‘Do not leave without me,’ she said. ‘I will be with you directly.’ She beckoned to Wymarc and made for the passage that led to her apartment.

As she hastened to her chamber, her mind was busy. What had prompted the ætheling’s generosity? On the few occasions that she had attempted to converse with Athelstan, he had been civil but hardly warm. She had given up trying to placate any of them – the king’s grown sons, the ladies of the court, the king himself. She felt like a pariah at the table and in the hall, for the king ignored her, and everyone else followed suit. What, then, had prompted Athelstan to seek the company of his father’s reviled queen?

She could not guess, yet she was certain that he had some hidden motive. Every word, every act, every gesture made at court was laced with cryptic intent. The very walls held secrets. And the king’s eldest son had reason to mislike and mistrust her, for she might one day bear a son to supplant him. She wished that it were not so, that she could ride today with a carefree heart. But she knew better. She would have to be wary.

Soon the cluster of riders was making its way past the mill, stringing out in smaller groups when they turned south to follow the path of the River Itchen. Emma found herself at Athelstan’s side, with Wymarc and Hugh – summoned by Emma because she wanted at least one of her Norman hearth guards with her – immediately behind them. Edward and Edgar, their rambunctious spirits kept in moderate check by two grooms, rode some way ahead, while the ætheling’s well-armed outriders trailed at a discreet distance.

As she rode Emma studied the young man beside her, looking for traces of his father. Their colouring was the same – hair as golden as ripe wheat, although Athelstan, like most English youth, wore his cropped roughly about his ears, in contrast to his father’s longer, perfectly groomed locks. They had the same high forehead as well, but there the similarity ended. Athelstan’s dark brows, broad nose, and full, sensuous lips bore no resemblance to his father’s thinner, more sharply sculpted features.

She studied his mouth and tried to recall if she had ever seen him smile. Not at her, certainly, which made her question again why he was riding beside her at this moment.

‘I am grateful for your kindness, my lord,’ she said. ‘The palace garden is quite beautiful, but I have longed to explore the countryside.’

‘My mother, who designed the garden,’ he said, ‘did not ride. She had a contemplative nature, and the garden seemed to satisfy all her needs.’

Emma considered what little she knew of his mother. The king’s first wife, it seemed, had lived like a nun, except for the very secular task of conceiving and bearing eleven children. Her personality seemed to have had all the impact on the king’s court of a finger drawn through water. Had she truly been content to live such a cloistered life, or had she been forced into it by the king? Emma could imagine that well enough. But perhaps the woman had never known any other kind of existence. Perhaps she had been raised in such a sheltered environment that she found the world beyond the garden walls terrifying and forbidding.

‘Your mother came from the north, I believe,’ she said. ‘You lived there for some little time, did you not? Does it look very different? Are the people different?’

‘The land,’ he said, ‘the people – even the language is different. They speak an odd mixture of English and Danish there, with occasional Norse thrown into the mix just for flavour. It is a harsher land, though, than this.’ He nodded towards the rolling green hills of the downs. ‘Not as rich. There are jagged peaks in the north, rising sheer sided, as if they’d been thrust up out of the bowels of the earth. To the west the land is gentler. That is the district of the lakes – God knows how many. They are cradled in green valleys, and when the sun shines they are as blue as sapphires. Towards the eastern coast, near Jorvik, the land is different yet again, for it is flat, but not without its own kind of wild beauty. In the spring it is a tapestry of flowers.’

Emma, astonished at this sudden spate of near poetry from one who had barely spoken a word to her until now, said, ‘Your eloquence, my lord, makes me long to see for myself these northern vistas. Perhaps the king’s progress will take me there some day.’

Athelstan shook his head. ‘My father went that far north only once, and then he had an army at his back. It is a dangerous place. The folk there are often restive under the rule of Wessex. Our strongholds, our history, lie here in the south.’

She recalled that Elgiva’s father was ealdorman of the northern lands. A dangerous place, Athelstan had said. And dangerous men and women were bred there, it seemed.

‘Is Elgiva a northerner?’ she asked.

‘Yes,’ he said hesitantly, ‘and no. Elgiva’s family owns half of Mercia, most of their lands lying in the area below the Northumbrian border. It’s what we call the Midlands, but the very northern edge of it. Mercia once had its own kings before it was conquered by Wessex, but that was in the distant past. Elgiva, though, often forgets that Mercia is no longer a kingdom, and that she is not a king’s daughter.’

Or a king’s wife, Emma thought. But if Elgiva’s family was so powerful, it would go some way to explaining why Æthelred singled her out for his favour.

‘What are the Northumbrians like, then?’ she asked. ‘The folk further north?’

He frowned.

‘Fifty years ago there was a northman named Eric Bloodaxe who ruled Northumbria and called it the Kingdom of Jorvik. He was driven out, but the folk there still maintain strong ties to the lands across the Northern Sea.’ He was not looking at her but kept his eyes firmly planted on the path ahead, so that his next words seemed casually offhand. ‘You have ties there as well, I think – of family and trade.’

Sensing danger in spite of his apparent disinterest, Emma replied flatly, ‘My mother’s people came from Denmark,’ she said, ‘but she grew up in Normandy.’

They were treading perilously close to a conversational landscape where she had no wish to venture. She believed that the king’s mistrust of her was rooted in her Danish forebears as well as in her brother’s lucrative trade with Viking shipmen. Had the king confided his suspicions to Athelstan? If so, then she had just given them credence by showing such an avid interest in the north. She wished that she had kept silent.

‘It is no secret,’ he said slowly, ‘that the Danish king, Forkbeard, has been entertained at the ducal palace in Normandy. I have never seen him, although I have heard a great deal about him. Were you there when your brother greeted him? Did you see the king?’

He looked at her now with steady blue eyes, but she saw no guile there, only curiosity. Still, she hesitated, uncertain what to say. She had no wish to emphasize her brother’s connection to Swein Forkbeard, but if Athelstan already knew that Swein had been in Normandy at Christmas, it would be foolish of her to lie.

‘I saw him last Yule-tide,’ she said, ‘but only briefly. My mother kept all the women of her household well away from the king and his shipmen.’

‘Ah,’ he said. ‘Yet he and his men were there at your brother’s invitation.’

She looked at him, irritated by his smug assumption that he understood her brother’s motives.

‘Indeed, my lord,’ she said. ‘And what would you do if an armed host, vastly outnumbering all your hearth troops and with a reputation for taking by force anything they wanted, appeared at your door demanding shelter?’

It was his turn to stare now, brows raised in surprise. Then he smiled.

‘I would invite them in,’ he said.

So she had made him smile at last. It lit his entire face and softened the hard edges of that square jaw. She had told him more than she would have wished, but, all in all, she thought that the result was worth the risk.

The conversation became less pointed after that. Emma questioned him about his brothers, eager to know more of Edmund and Ecbert in particular, whom she had had little opportunity to observe. He asked about her own brothers and sisters, and was curious about the training that her brother Richard had devised for his horses.

It seemed to Emma that the time passed all too quickly, and she was sorry when they halted before the king’s great hall.

‘Perhaps,’ Athelstan said, as he helped her to dismount, ‘we might ride together again. I would learn more of Normandy, if you would be willing to instruct me.’

He stood facing her, his hands still at her waist exerting a gentle pressure to steady her. Only his touch did not steady her. It did the opposite, and when she looked into his eyes, far bluer than the sky, she felt dizzy, as if she were falling from some great height.

‘I do not know if the king would give me leave,’ she answered, backing away from him, seeking solid ground.

‘I will speak to him. He should have no objection, so long as he is assured that you will be safe.’

Safe? Was there anywhere in this realm where she could be truly safe? It was a world peopled with men and women scheming for power and preferment, and her marriage had bred resentment towards her that could one day turn to enmity, and against which she had little defence.

As she watched him lead the horses towards the stable, she pondered the wisdom of riding out with him again. She still did not know why he had made this overture towards her, but, dear God, she longed to escape the suffocating world within the palace walls. Why should she not attend him, if the king allowed it? She needed to forge alliances within the court. Perhaps this was a beginning.

Or perhaps, she argued with herself, it was a trap of some kind, devised to destroy her already precarious relationship with the king. How was she to tell?

She turned to follow Wymarc, who was shepherding the younger boys into the private apartments. There was no one at court, she reminded herself, whom she could truly trust, except her own people. She must remember that.

But as she made her way up the stairs, slowly, for her legs ached from their unaccustomed exercise, she was troubled by a too vivid memory of piercing blue eyes and the sudden shifting of the earth beneath her feet.