Читать книгу Lempicka - Patrick Bade - Страница 2

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление* * *

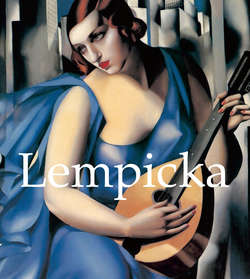

Self-Portrait in the Green Bugatti, 1929

Oil on panel, 35 × 27 cm

Private Collection

Biography

1898

Born Tamara Gurwik-Gorska in Warsaw to wealthy, upper-class Polish parents. Her father, Bolris Gorski, was a lawyer with a French firm. Her mother was Malvina Decler.

1911

A trip to Italy with her grandmother helps Tamara discover her passion for art.

1914

Tamara moves in with her aunt Stephanie in St Petersburg, resenting her mother’s decision to remarry. She meets her future husband, Tadeusz Lempicki, a handsome lawyer from a wealthy Russian family.

1916

Tamara and Tadeusz marry in Petrograd in the chapel of the Knights of Malta.

1917

Russia is engulfed in revolution after the rise of the Bolsheviks and the new regime.

1918

Tadeusz is arrested as a counter-revolutionary. Tamara enlists the help of the Swedish consul to help him escape. They both manage to flee the country and are reunited in Paris, their home for the next 20 years.

1920

Birth of Kizette de Lempicka. Tamara takes classes with Maurice Denis and Andre Lhote. She takes the name Tamara de Lempicka and begins to develop her worldly, modish and erotic style.

1922

She sells her first paintings from the Gallerie Colette Weill, later exhibiting her work for the first time at the Salon d’Automne in Paris.

1925

De Lempicka makes a name for herself with a one woman show at the Bottega di Poesia in Milan and at the world’s first Art Deco exhibition, held in Paris. The German fashion magazine Die Dame commissions one of her most famous paintings, the Self-Portrait in the Green Bugatti.

1926

The great Italian poet and playwright, Gabriele d’Annunzio, makes a failed attempt to seduce de Lempicka at his villa on the Italian coastline.

1927

De Lempicka completes several controversial paintings of her daughter Kizette. She meets the beautiful Rafaela in the Bois de Boulogne who inspires some of her most sensuous and erotic works.

1928

She begins work on her Boucet family commissions and paints a portrait of her husband Tadeusz before their divorce later in the year. She meets Baron Raoul Kuffner and moves into a spacious apartment in rue Méchain designed by the fashionable modernist architect Robert Mallet-Stevens.

1929

De Lempicka becomes Kuffner’s mistress and makes her first trip to America.

1933

She marries Baron Kuffner. Her work and creativity suffer after the sobering realities of Hitler’s ascension to power in Germany and the Wall Street Crash. She enters a long period of depression.

1939

De Lempicka and Baron Kuffner move to America and settle in Los Angeles after Kuffner sells off most of his Austrian and Hungarian estates. De Lempicka continues to paint and slips easily into the glamorous world of Hollywood high society.

1942

Tired of their life in Hollywood, Kuffner insists they move back to New York. Kizette joins them in America where she meets her husband, Harold Foxhall, a geologist from Texas.

1943

Her new life as a New York socialite detracts from her art. Her figurative paintings and experiments with abstract expressionism fail to attract any interest. Her career begins to stall and she fades slowly into obscurity.

1962

Baron Kuffner dies. A distraught de Lempicka moves in with her daughter and husband in Houston.

1973

A renewed interest in her work leads to a hugely successful retrospective show of her work at the Galerie du Luxembourg.

1974

Her fame restored, she moves in with her daughter in Cuernavaca, Mexico, living the rest of her life marred by her irascibility in her dealings with her family and the rest of the world.

1980

Tamara de Lempicka dies on March 18th leaving instructions for her ashes to be scattered over the crater of the volcano Popocatepetl.

* * *

Tamara de Lempicka created some of the most iconic images of the twentieth century. Her portraits and nudes of the years 1925–1933 grace the dust jackets of more books than the work of any other artist of her time. Publishers understand that in reproduction, these pictures have an extraordinary power to catch the eye and kindle the interest of the public. In recent years, the originals of the images have fetched record sums at Christie’s and Sotheby’s. Beyond the purchasing power of most museums, these paintings have been eagerly collected by film and pop stars. In May 2004, the Royal Academy of Arts in London staged a major show of de Lempicka’s work just one year after she had figured prominently in another big exhibition of Art Deco at the Victoria and Albert museum.

The Chinese Man

c. 1921

Oil on canvas, 35 × 27 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts du Havre

The public flocked to the show despite a critical reaction of unprecedented hostility towards an artist of such established reputation and market value. In language of moral condemnation hardly used since Hitler’s denunciations of modern art at the Nuremberg rallies and the Nazi-sponsored exhibition of Degenerate Art, the art critic of the Sunday Times, Waldemar Januszczak, fulminated “I had assumed her to be a mannered and shallow peddler of Art Deco banalities. But I was wrong about that. Lempicka was something much worse. She was a successful force for aesthetic decay, a melodramatic corrupter of a great style, a pusher of empty values, a degenerate clown and an essentially worthless artist whose pictures, to our great shame, we have somehow contrived to make absurdly expensive.”

Woman Wearing a Shawl, in Profile

c. 1922

Oil on canvas, 61 × 46 cm

Barry Friedman Ltd, New York

According to Januszczak, de Lempicka did not arrive in Paris in 1919 as an innocent refugee from the Russian Revolution but on a sinister mission, intending “an assault on human decency and the artistic standards of her time”. One cannot help wondering what it was about de Lempicka’s art that should bring down upon it such hysterical vituperation. There is a clue perhaps in his waspish observation “Luther Vandross collects her, apparently. Madonna. Streisand. That type.” The hostility is perhaps more politically than aesthetically motivated and what really got under the skin of certain critics was the glamorous life style of Tamara’s collectors as well as of her sitters.

Bouquet of Hortensias and Lemon

c. 1922

Oil on canvas, 55.2 × 45.7 cm

Barry Friedman Ltd, New York

Both the place and the date of de Lempicka’s birth vary in different accounts. According to some, de Lempicka changed her birth place from Moscow to Warsaw which could be more significant. There has been speculation that de Lempicka was of Jewish origin on her father’s side and that the deception over her place of birth resulted from an attempt to cover this up. Certainly the ability to reinvent oneself time and again in new locations, manifested by de Lempicka throughout her life was a survival mechanism developed by many Jews of her generation. The prescience of the danger of Nazi Germany in a woman not usually politically minded and her desire to leave Europe in 1939 might also suggest that she was part Jewish. The official version was that Tamara Gurwik-Gorska was born in 1898 in Warsaw into a wealthy and upper-class Polish family.

The Fortune Teller

c. 1922

Oil on canvas, 73 × 59.7 cm

Barry Friedman Ltd, New York

Following three partitions in the late eighteenth century, the larger part of Poland including Warsaw was absorbed into the Russian Empire. The rising tide of nationalism in the nineteenth century brought successive revolts against Russian rule and increasingly harsh attempts to Russify the Poles and to repress Polish identity. There is little to suggest that Tamara ever identified with the cultural and political aspirations of the Polish people. On the contrary, she seems to have identified with the ruling classes of the Tzarist regime that oppressed Poland. It is telling that in 1918 when she escaped from Bolshevist Russia she chose exile in Paris along with thousands of Russian aristocrats rather than to live in the newly liberated and independent Poland. From what Tamara herself later said, she seems to have enjoyed a happy childhood with her older brother Stanczyk and her younger sister Adrienne.

Portrait of a Young Lady in a Blue Dress

1922

Oil on canvas, 63 × 53 cm

Barry Friedman Ltd, New York

The wilfulness of her temperament, apparent from an early age, was indulged rather than tamed. The commissioning of a portrait of Tamara at the age of twelve turned into an important and revelatory event. “My mother decided to have my portrait done by a famous woman who worked in pastels. I had to sit still for hours at a time…more…it was a torture. Later I would torture others who sat for me. When she finished, I did not like the result, it was not… precise. The lines, they were not fournies, not clean. It was not like me. I decided I could do better. I did not know the technique. I had never painted, but this was unimportant. My sister was two years younger. I obtained the paint. I forced her to sit. I painted and painted until at last, I had a result. It was imparfait but more like my sister than the famous artist’s was like me.”

Portrait of a Polo Player

c. 1922

Oil on canvas, 73 × 60 cm

Barry Friedman Ltd, New York

If Tamara’s vocation was born from this incident as she suggests, it was encouraged further the following year when her grandmother took her on a trip to Italy. Visits to museums in Venice, Florence and Rome lead to a life long passion for Italian Renaissance art that informed de Lempicka’s finest work in the 1920s and 30s. A torn and crumpled photograph of Tamara taken in Monte Carlo shows her as a typical young girl de bonne famille of the period before the First World War. Her lovingly combed hair cascades with Pre-Raphaelite abundance over her shoulders and almost down to her waist. She poses playing the children’s game of diabolo but her voluptuous lips and coolly confident gaze belie her thirteen years. It would not be long before she would be ready for the next great adventure of her life – courtship and marriage.

The Kiss

c. 1922

Oil on canvas, 50 × 61 cm

Private Collection

Played against the backdrop of the First World War and the death throes of the Russian monarchy, the story as passed down by Tamara and her daughter is, as so often in de Lempicka’s life, worthy of a popular romantic novel or movie. When Tamara’s mother remarried, the resentful daughter went to stay with her Aunt Stephanie and her wealthy banker husband in St. Petersburg, where she remained trapped by the outbreak of war and the subsequent German occupation of Warsaw. Just before the war when Tamara was still only fifteen, she spotted a handsome young man at the opera surrounded by beautiful and sophisticated women and instantly decided that she had to have him. His name was Tadeusz Lempicki.

Nude, Blue Background

1923

Oil on canvas, 70 × 58.5 cm

Private Collection

Though qualified as a lawyer, he was something of a playboy, from a wealthy land-owning family. With her customary boldness and lack of inhibitions, the young girl flouted convention by approaching Tadeusz and making an elaborate curtsey. Tamara had the opportunity to reinforce the impression she had made on Tadeusz at their first meeting when later in the year, her uncle gave a costume ball to which Lempicki was invited. In amongst the elegant and sophisticated ladies in the Poiret-inspired fashions of the the day, Tamara appeared as a peasant, goose-girl leading a live goose on a string.

A Street at Night

c. 1923

Oil on canvas, 50 × 33.5 cm

Private Collection

Barbara Cartland and Georgette Heyer could not have invented a ploy more effective for catching the eye of the handsome hero. In an account that has the ring of truth to it, Tamara admitted that the brokering of her marriage to Tadeusz by her Uncle was less than entirely romantic. The wealthy banker went to the handsome young man about town and said “Listen. I will put my cards on the table. You are a sophisticated man, but you don’t have much fortune. I have a niece, Polish, whom I would like to marry. If you will accept to marry her, I will give her a dowry. Anyway, you know her already.”

Seated Nude in Profile

c. 1923

Oil on canvas, 81 × 54 cm

Barry Friedman Ltd, New York

By the time the marriage took place in the chapel of the Knights of Malta in the recently re-named Petrograd in 1916, Romanov Russia was on the verge of collapse under the onslaught of the German army and on the point of being engulfed in revolution. The tribulations of the newly married couple after the rise of the Bolsheviks belong not so much to the plot of a novel as of an opera, with Tamara cast in the role of Tosca and Tadeusz as Cavaradossi. Given the background and life-style of the couple and the reactionary political sympathies and activities of Tadeusz, it was not surprising that he should have been arrested under the new regime. Tamara remembered that she and Tadeusz were making love when the secret police pounded at the door in the middle of the night and hauled Tadeusz off to prison.

Seated Nude

c. 1923

Oil on canvas, 94 × 56 cm

Private Collection

In her efforts to locate her husband and to arrange for his escape from Russia, Tamara enlisted the help of the Swedish consul who like Scarpia in Puccini’s operatic melodrama, demanded sexual favours. Happily the outcome was different from that of Puccini’s opera and neither party cheated the other. Tamara gave the Swedish consul what he wanted and he honoured his promise, not only to aid Tamara’s escape from Russia but also the subsequent release and escape of her husband. Tamara travelled on a false passport via Finland to be re-united with relatives in Copenhagen.

The Sleeping Girl

1923

Oil on canvas, 89 × 146 cm

Private Collection

Refugees from the Russian Revolution fanned out across the globe, but Paris which had long been a second home to well-healed Russians, became a Mecca for White Russians in the inter war period. Inevitably Tamara and Tadeusz were drawn there along with Tamara’s mother and younger sister (her brother was one of the millions of casualties of the war). Unlike so many refugees who arrived there penniless and friendless they could at least rely upon help from Aunt Stefa and her husband who had managed to retain some of his wealth and to re-establish himself in his former career as a banker.

Perspective

1923

Oil on canvas, 130 × 162 cm

Musée du Petit Palais, Genève

From the turn of the century the political alliance between Russia and France – aimed at containing the menace of Wilhelmine Germany – encouraged the growth of cultural links between the two countries. The great impresario Sergei Diaghilev took advantage of this political climate to establish himself in Paris. In 1906, Diaghilev organised an exhibition of Russian portraits at the Grand Palais that pioneered a more imaginative presentation of paintings and sculptures. Following this success, he arranged concerts that for the first time presented to the French public the music of such composers as Glazunov, Rachmaninov, Rimsky-Korsakov, Tchaikovsky and Scriabin.

The Gypsy

c. 1923

Oil on canvas, 73 × 60 cm

Private Collection

Diaghilev’s designers, notably Leon Bakst, played a vital role in developing the Art Deco style with which de Lempicka became associated. In particular Bakst’s designs for the 1910 production of Sheherazade had an extraordinary impact on fashion and interior design. For the next generation, fashionable Parisian hostesses dressed themselves and decorated their salons as though for an oriental orgy. Even in the late 1920s, photographs of Tamara de Lempicka’s bedrooms show decors which, though much pared down from the lushness of Bakst’s designs, make them look as if Nijinsky’s sex slave would not be out of place as an overnight guest.

Woman in a Black Dress

1923

Oil on canvas, 195 × 60.5 cm

Private Collection

Paris in the inter-war period was teeming with Russian refugees. It was jokingly said that every second taxi driver in Paris was either a real or pretend Grand Duke.

De Lempicka’s early years in Paris were not happy. Though never reduced to the penury of so many of her refugee compatriots, she was nevertheless dependent upon the largesse of her wealthier relations. Despite the birth of her daughter Kizette, Tamara’s love match with Tadeusz was turning sour as a result of her own infidelities and his frustrations. He refused as demeaning the offer of a job in her uncle’s bank. According to her own account it was out of this grim situation and a desire for financial and personal independence that de Lempicka’s artistic vocation was born.

Double “47”

c. 1924

Oil on panel, 46 × 38 cm

Private Collection

Tamara confessed her plight to her younger sister Adrienne, resulting in the following conversation between the sisters; – “Tamara, why don’t you do something – something of your own? Listen to me, Tamara. I am studying architecture. In two years I’ll be an architect, and I’ll be able to make my own living and even help out Mama. If I can do this, you can do something too” “What? What? What?” “I don’t know, painting perhaps. You can be an artist. You always loved to paint. You have talent. That portrait you did of me when we were children….” The rest, as they say, was history. Tamara bought the brushes and paints, enrolled in an art school, sold her first pictures within months and made her first million (francs) by the time she was twenty-eight.

Portrait of Kizette

c. 1924

Oil on canvas, 135 × 57 cm

Private Collection

Tamara took herself for tuition to two distinguished painters in succession: Maurice Denis (1870–1943) and André Lhote (1885–1962). De Lempicka later claimed that she did not gain much from Denis. It is indeed difficult to imagine that the intensely Catholic Denis would have been much in sympathy with the worldly, modish and erotic tendencies that soon began to display themselves in Tamara’s work. Nevertheless Denis was an intelligent initial choice as a teacher for the aspiring artist. For a brief period in the early 1890s Denis had been at the cutting edge of early modernism as a leading member of the Nabis group that included Vuillard, Bonnard, Serusier, Ranson and Vallotton.

Rhythm

1924

Oil on canvas, 160 × 144 cm

Private Collection

Inspired by the Synthetism of Gauguin’s Breton paintings, Denis and his friends broke with the naturalism of Salon painting and the very different naturalism of the Impressionists who were tied to sensory perception and painted small pictures in flat patches of bright, exaggerated colours. However the firm linearity and smooth modelling of the forms in Denis’ later works as well as his attempts to marry modernity with the classical tradition can hardly have failed to influence the young de Lempicka. The aesthetic expressed by Denis in his 1909 publication From Gauguin and Van Gogh to Classicism was surely one with which she would have agreed. “Art is not simply a visual sensation that we receive… a photograph however sophisticated of nature. No, it is a creation of the mind, for which nature is merely the springboard.” This is surely true of de Lempicka’s strangely cerebral and abstracted portraits of the 1920s.

Irene and Her Sister

1925

Oil on canvas, 146 × 89 cm

Irena Hochman Fine Art Ltd, New York

De Lempicka was far more ready to acknowledge the influence of her second teacher André Lhote. Whilst Denis must have seemed like a relic of the nineteenth century, Lhote, born in 1885, was not much more than a decade older than de Lempicka herself and was much closer to her modern and worldly outlook. Lhote had been associated with cubism since 1911 when he exhibited at the Salon des Independents and the Salon d’Automne alongside artists such as Jean Metzinger, Roger de La Fresnaye, Albert Gleizes and Fernand Leger. Rather than following the radical experiments in the dissolution of form in Picasso and Braque’s Analytical Cubism, he was attracted to the brightly coloured and more representational Synthetic Cubism of Juan Gris, Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger.

Nude on a Terrace

1925

Oil on canvas, 37.8 × 54.5 cm

Private Collection

For Lhote, painting was a “plastic metaphor…pushed to the limit of resemblance”. In words not so different from those of Denis, he maintained that artists should aim to express an equivalence between emotion and visual sensation, rather than to copy nature. What made Lhote particularly useful to de Lempicka as an example and as a teacher was the acceptance of the decorative role of painting and also his attempt to fuse elements of cubist abstraction and disruption of conventional perspective with the figurative and classical tradition. If the artist de Lempicka did not spring to life fully formed and fully armed like Athena from the head of Zeus as she would have us believe, the gestation period of her mature art was remarkably short – lasting two or three years at most.

Seated Nude

c. 1925

Oil on canvas, 61 × 38 cm

Private Collection

Her Portrait of a Polo Player painted around 1922 already shows her predilection for the smart set but could otherwise have been painted by any competent artist trained in Paris in these years. It has a looseness of touch and a painterly quality that would soon disappear from her work. The modelling of the face in bold structural brush strokes shows an awareness of Cezanne that would undoubtedly have been encouraged by both Denis and Lhote. Similarly lush and painterly is the portrait of Ira Perrot later re-titled Portrait of a Young Lady in a Blue Dress. In its original form, as exhibited at the Salon d’Automne and photographed at the time with the model in front of it, it showed Ira Perrot seated cross-legged in front of cushions piled up exotically in the manner of Bakst’s Sheherazade designs.

Seated Nude

1925

Oil on canvas, 61 × 38 cm

Private Collection

More prophetic both stylistically and in subject matter than these two portraits is another canvas of the same period entitled The Kiss. The erotic theme, played out against an urban back-drop, the element of cubist stylisation that gives the picture an air of modernity and dynamism and the metallic sheen on the gentleman’s top hat all anticipate de Lempicka’s artistic maturity. The crudeness of the technique is as yet far from the enamelled perfection of her best work. Naivety is not in general a quality we associate with de Lempicka but this picture has the look of a cover for a lurid popular novel.

The Model

1925

Oil on canvas, 116 × 73 cm

Barry Friedman Ltd, New York

The following year we find de Lempicka working on a series of large scale and monumental female nudes that might be described as cubified rather than Cubist. These works reflect an interest in the classical and the monumental that was widespread in Western art following the First World War and throughout the inter-war period.

The entire history of Western art from the Ancient world onwards can be seen in terms of a series of major and minor classical revivals. In an essay of 1926 entitled The Call to Order, Jean Cocteau presented the post-war return to classicism as a necessary reaction to the chaos of radical experimentation during the anarchic decade that had preceded the First World War. There was undoubtedly some element of truth in this, though the roots of inter-war classicism can be traced back much further.

Group of Four Nudes

c. 1925

Oil on canvas, 130 × 81 cm

Private Collection

A specifically French version of classicism can be seen as a continuing thread in French art running back as far as Poussin in the seventeenth century. The classicist most often cited in connection with de Lempicka is the nineteenth century painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867). The taste for hard, bright colours and enamelled surfaces, the combination of abstraction and quasi-photographic realism, the eroticising of the female body through the radical distortion of anatomy and the love of luxurious and fashionable accessories link the female portraits of Ingres and de Lempicka.

Two Little Girls with Ribbons

1925

Oil on canvas, 100 × 73 cm

Dr George and Mrs. Vivian Dean’s Collection

Baudelaire’s bitchy comment that Ingres’ ideal was “A provocative, adulterous liaison between the calm solidity of Raphael and the affectations of the fashion plate” could apply equally well to de Lempicka. What is perhaps more surprising is the way de Lempicka follows Ingres’ example in treating women as passive sex objects. Like Ingres she shows virtually no interest in the individual psychology or personality of her female sitters. De Lempicka’s female nudes are still more closely linked to Ingres. Her chained and swooning Andromeda with her upturned eyes and head thrown further back than anatomy should allow, against a cubified urban backdrop, is clearly an updated version of Ingres’ Angelica. Her groups of female nudes piled up like inflatable dolls, descend from Ingres’ notorious Turkish Bath.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Купить книгу