Читать книгу Mucha - Patrick Bade - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSince the Art Nouveau revival of the 1960s, when students around the world adorned their rooms with reproductions of Mucha posters of girls with tendril-like hair and the designers of record sleeves produced Mucha imitations in hallucinogenic colours, Alphonse Mucha’s name has been irrevocably associated with the Art Nouveau style and with the Parisian fin-de-siècle.

Gismonda

1894

Colour lithograph, 216 × 74.2 cm.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

Artists rarely like to be categorised and Mucha would have resented the fact that he is almost exclusively remembered for a phase of his art that lasted barely ten years and that he was regarded as of lesser importance. As a passionate Czech patriot he would have also been unhappy to be regarded as a “Parisian” artist.

La Dame aux camélias

1896

Colour lithograph, 205 × 72 cm.

Richard Driehaus, Chicago.

Mucha was born on July 14, 1860 at Ivancice in Moravia, then a province of the vast Habsburg Empire. It was an empire that was already splitting apart at the seams under the pressures of the burgeoning nationalism of its multi-ethnic component parts. In the year before Mucha’s birth, nationalist aspirations throughout the Habsburg Empire were encouraged by the defeat of the Austrian army in Lombardy that preceded the unification of Italy.

Journée Sarah (La Plume)

1896

Colour lithograph, 69 × 50.8 cm

Posters Please Inc., New York.

In the first decade of Mucha’s life Czech nationalism found expression in the orchestral tone poems of Bedrich Smetana that he collectively entitled “Ma Vlast” (My country) and in his great epic opera “Dalibor” (1868). It was symptomatic of the Czech nationalist struggle against the German cultural domination of Central Europe, in that the text of “Dalibor” had to be written in German and translated into Czech.

Biscuits Champagne Lefèvre-Utile

1896

Colour lithograph, 51.4 × 32 cm.

Mucha Trust.

From his earliest days Mucha would have imbibed the heady and fervent atmosphere of Slav nationalism that pervades “Dalibor” and Smetana’s subsequent pageant of Czech history, “Libuse”, which was used to open the Czech National Theatre in 1881 and for which Mucha himself would later provide set and costume designs.

Cassan Fils

1896

Colour lithograph, 203.7 × 76 cm.

Mucha Trust.

Mucha’s born into relatively humble circumstances, as the son of a court usher. His own son, Jiri Mucha, would later proudly trace the presence of the Mucha family in the town of Ivancice back to the fifteenth century. If his family was poor, Mucha’s upbringing was nevertheless abundant with artistic stimulation and encouragement.

Self Portrait

1899

Oil on cardboard, 21 × 32 cm.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

According to his son Jiri, “He drew even before he learnt to walk and his mother would tie a pencil round his neck with a coloured ribbon so that he could draw as he crawled on the floor. Each time he lost the pencil, he would start howling.” His first important aesthetic experience would have been in the Baroque church of St. Peter in the local capital of Brno where, from the age of ten, he sang as a choir-boy in order to support his studies in the grammar school. During his four years as a chorister he came into frequent contact with Leoš Janácek, who would later come to be known as the greatest Czech composer of his generation with whom Mucha shared a passion to create a characteristically Czech art.

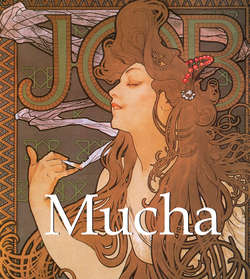

Poster for “Job” cigarette paper

1898

Colour lithograph, 149.2 × 101 cm.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

Poster advertising the Salon des Cent Exposition at the Hall de la Plume

1896

Colour lithograph, 64 × 43 cm.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

The luxurious theatricality of Central European Baroque with its lush curvilinear and nature-inspired decoration undoubtedly coloured his imagination and inspired a taste for “smells and bells” and religious paraphernalia that remained with him throughout his life. At the height of his fame, his studio was described as being like a “secular chapel… screens placed here and there, that could well be confessionals; and then incense burning all the time. It’s more like the chapel of an oriental monk than a studio.” While earning a living as a clerk, Mucha continued to indulge his love of drawing and in 1877 he gathered together his self-taught body of work and attempted unsuccessfully to enter the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague.

Spring (from the Seasons series)

1896

Colour lithograph, 28 × 15 cm.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

Summer (from the Seasons series)

1896

Colour lithograph, 28 × 15 cm.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

After two more years of drudgery as a civil servant, he lost his job, according to Jiri Mucha, because he drew the portraits of a picturesque family of gypsies instead of taking down their particulars. In 1879 he spotted an advertisement in a Viennese newspaper for the firm of Kautsky-Brioschi-Burghardt, makers of theatrical scenery who were looking for designers and craftsmen.

Autumn (from the Seasons series)

1896

Colour lithograph, 28 × 15 cm.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

Mucha sent off examples of his work and this time he was successful and received an offer for a job.

As a country boy who had been no further than the picturesque (but still provincial) Prague, Vienna in 1879 must have looked awesomely grand.

Winter (from the Seasons series)

1896

Colour lithograph, 28 × 15 cm.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

It had recently undergone what was, after Haussmann’s Paris, the most impressive scheme of urban renewal of the nineteenth century. Each of the great public buildings lining the Ringstrasse, which replaced the old ramparts that had encircled the medieval town centre, was built in a historical style, deemed appropriate to its purpose.

Study for Zodiac

1896

Pencil, ink and watercolour on paper, 67 × 48 cm.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

The result was a grandiose architectural fancy-dress ball. The Art Nouveau style, of which Mucha would later become one of the most famous representatives, reacted directly against this kind of pompous wedding cake historicism. For the moment though, Mucha was deeply influenced by the showy and decorative art of Hans Mackart, the most successful Viennese painter of the Ringstrasse period.

Zodiac

1896

Colour lithograph, 67 × 48 cm.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

After barely two years, Mucha’s Viennese sojourn came to an abrupt end. On December 10th, 1881, the Ringtheater burnt down. In a century punctuated by terrible theatre fires, this was one of the worst, claiming the lives of over five hundred members of the audience. The Ringtheater was also one of the principal clients of the firm of Kautsky-Brioschi-Burghardt and in the aftermath of the disaster, Mucha lost his job.

Flower

1897

Colour lithograph, 66 × 44 cm.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

Mucha moved to the small town of Mikulov and fell back upon the time-honoured artistic tradition of making ends meet: making portraits of local dignitaries. His unusual way of attracting a clientele is related in his memoirs. He booked a room at the “Lion Hotel” and managed to sell a drawing of some local ruins to a dealer called Thiery who displayed it in his shop window and quickly sold it on.

Fruit

1897

Colour lithograph, 66 × 44 cm.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

So I got busy drawing again, not ruins this time, but the people around me. I painted the head of a pretty woman and brought it to Thiery. He put it into the window and I began to look forward to the cash. When there was no news from Thiery for two and even three days, I went to ask him myself. The good man wasn’t pleased to see me. Mikulov society was filled with indignation, and my picture had to be taken out of the window.

Vin des Incas

1897–1899

Colour lithograph, 13.6 × 36 cm.

Mucha Trust.

The young lady I had painted was the wife of the local doctor, and Thiery had put a notice next to the portrait saying, ‘For five florins at the Lion Hotel’. The scandal was duly explained and in the end worked out to my advantage. The whole town knew that a painter had come to live at the Lion. In the course of time, I painted the whole neighbourhood – all the uncles and aunts of Mikulov.

Monaco – Monte-Carlo

1897

Colour lithograph, 110 × 76 cm.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

It was while he was living in Mikulov that Mucha encountered the first of the two patrons who were to transform his career. One was a wealthy local landowner called Count Khuen, who invited Mucha to decorate the dining room in the newly-built castle of Emmahof with frescoes. This was Mucha’s first encounter with murals and initiated a life-long ambition of paint large-scale decorative work.

Salon des Cent: Exposition de l’Œuvre de Mucha

1897

Colour lithograph, 67 × 47 cm.

Mucha Museum, Prague.

Even the posters of the 1890s, on which Mucha’s fame now largely rests, can be seen as reflecting this desire to decorate walls. Such a desire was common to many artists of the fin-de-siècle. The large scale decorative paintings of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, the most widely-admired and influential artist of the period, were commonly referred to as “fresques” though they were in fact oil paintings on canvas that simulated the effect of frescoes.

Bières de la Meuse

1897

Colour lithograph, 155 × 104.5 cm.

Park South Gallery at Carnegie Hall, New York.

The manifesto of the Symbolist “Salon de la Rose-Croix” set up in 1892 by “Sar” Joséphin Péladan, stated “The Order prefers work which has a mural-like character as being of superior essence”. The paintings of Edvard Munch’s “Frieze of Life” and the flat, stylised canvases of Gauguin could be regarded as “fresques manquées”.

Brunette

1897

Colour lithograph, 34.5 × 28 cm.

Mucha Trust.

Albert Aurier, the very first critic who attempted to introduce Gauguin’s work to the French public wrote “You have among you a decorator of genius. Walls! Walls! Give him walls!”. We can only judge Mucha’s murals for Count Khuen from dim black and white photographs as the originals were destroyed in the final days of the Second World War but they were no doubt fairly conventional and academic as all his work would be for the next few years.

Blond

1897

Colour lithograph, 56 × 34.8 cm.

Mucha Trust.

When the first set of murals was finished at Emmahof, Count Khuen passed Mucha on to his brother Count Egon, who lived in the ancestral castle of Gandegg in the Tyrol, who in turn sent Mucha off for a period of study in Munich.

La Plume

1897

Colour lithograph, 25 × 18 cm.

Mucha Trust.

After Bavaria was raised to the dignity of a kingdom early in the nineteenth century, King Ludwig determined that his capital should become the cultural capital of central and German-speaking Europe. The public buildings he commissioned in Neoclassical and Neo-Renaissance style made his desire that Munich be seen as the Athens or the Florence of the North clear to the world.

Cover for Chansons d’aïeules

1897

Colour lithograph, 33 × 25 cm.

Collection of Victor Arwas, London.

By the end of the century, Munich was regarded by many as a serious alternative to Paris. Amongst the aspiring artists who were attracted to Munich were Lovis Corinth, Wassily Kandinsky, Alexei von Jawlensky, Paul Klee and Giorgio de Chirico. Even the young Picasso briefly considered going to Munich in preference to Paris.

Decorative Plate with Symbol of Paris

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Купить книгу