Читать книгу Walking in the Ochils, Campsie Fells and Lomond Hills - Patrick Baker - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPRACTICALITIES

How to Use this Guide

The walks are divided into three sections, one for each range of hills, and each section opens with an introduction to the area. All the route descriptions begin with a summary of information, along with an overview of what can be expected on the walk, including any significant details concerning terrain and navigation. The summary includes the distance, height gain and approximate time required for the walk (the time estimated for each walk is calculated at a walking speed of 5km an hour, using Naismith's Rule for ascent, and does not include time taken for breaks), as well as the required map and a difficulty rating.

The maps in the guide are from the OS 1:50,000 Landranger series, but it is highly advisable to also carry the relevant OS 1:25,000 Explorer or Harvey's 1:25,000 maps (identified in the summary at the start of the walk), as many routes require intricate map referencing unavailable on the larger 1:50,000 maps. The difficulty rating takes into account navigation, terrain and time spent on the hill, and ranges from 1, which is an easily manageable route such as Walk 24, Dungoil in the Campsie Fells, to 4 for routes such as Walk 20, the Round of Nine in the Ochils, which involves long distances, some difficult terrain underfoot and potentially complicated navigating.

A basic level of ability in macronavigating is assumed, as is the understanding of grid references, map orientation, gradients, map symbols and estimation of distances. For more challenging routes the ability to use a compass in setting and walking on bearings is crucial, as are micro-navigational skills involved in timing and pacing distances.

Quite often route descriptions will refer to ‘attack points’. These are obvious features that are aimed for en route to a less visible destination point near the ‘attack point’. Many of the routes also use obvious linear features in the landscape – such as a burn, the edge of a forest or a fenceline – as useful ‘navigational handrails’ that lead the walker on to the next obvious feature on a route.

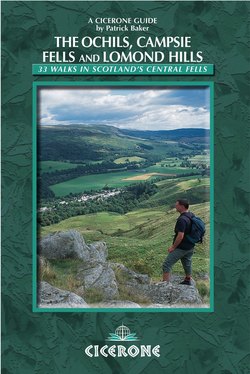

A view of Dumgoyne in the Campsie Fells (Walk 21)

Planning and Preparation

An element of risk is inherent in all the hills and wild places visited in this guide. Fortunately, careful planning and preparation can minimise potential risks, and the hills can be enjoyed safely and respectfully.

Before setting out, careful consideration should be given to whether the demands of a particular walk can be met by the fitness, equipment, experience and skills of those undertaking it. For example, it would be foolish for a walker with only basic map reading skills to attempt a route through featureless terrain in poor visibility.

When a walk has been selected, a ‘route card’ (a simple description of the route to be taken, along with an estimated time to arrive back and a note of the number of people in the group) should be left with someone who can anticipate your return.

Weather conditions should also be taken into account before starting out – obtain accurate, up-to-date local forecasts where possible. The route descriptions assume summer conditions prevail, but our maritime climate means that extreme weather is possible at any time of the year, and it should be assumed that a variety of conditions may occur in one day. When planning a walk the effects of weather should factored into the demands of the route, as strong winds and driving rains can be both energy sapping and demoralising, although hot and still days may have equally debilitating effects. Clothing and equipment should also be planned in advance to match the prevailing and expected conditions.

As well as being prepared with essential equipment (listed in the section below), some dietary preparation before and during a walk will be of benefit. The complex carbohydrates in starchy foods such as pasta, rice and wholemeal bread take longer to be broken down into an energy-giving form, so these are excellent for releasing energy evenly over longer periods, and are best consumed some time before a walk.

On the hill, a mix of different food groups will result in a sustained release of energy. Some typical foods to be packed in the rucksack could consist of those high in carbohydrates and fat, such as peanut butter wholemeal sandwiches, as well as those that supply natural sugars, such as dried fruit, proteins from seeds and nuts, and quick-release energy foods such as chocolate.

It is also important to replace the large amounts of fluid lost from the body during hillwalking. Burns and rivers are encountered on almost every walk in this guide, but the large amount of livestock found in most areas means that water collected during a walk may well be contaminated, so it is essential for enough water (1–1.5 litres is as an initial guide for an average-length walk) to be carried and consumed throughout a walk, with the principle of drinking ‘small amounts often’ to avoid the effects of dehydration.

Essential Equipment

Appropriate clothing for the conditions likely to be experienced is key to an enjoyable and safe day's walking. Scotland is subject to the fickle nature of our climate more so than many other areas of Britain, so even in summer, clothing needs to be able to adapt to sudden changes in weather. Despite recent innovations in the use of single, multipurpose garments, the most reliable method of combating changeable conditions is the layering principle, allowing the walker to achieve insulation and warmth, as well as protection from the elements, by combining different layers of clothing for specific purposes.

An excellent viewpoint along Endrick Water from Dunmore (Walk 26)

For the base layer, next to the skin, synthetic material such as polypropylene provides good insulation while transferring or ‘wicking’ perspiration away from the skin through to the layers of the outer garments. (Cotton t-shirts have the opposite effect – of storing moisture – and are thus unsuitable for colder conditions where they chill the body easily.) On top of the base layer, thicker, insulating garments, such as a fleece or woollen jumper, should be worn for heat retention, after which the outer layer or ‘shell’ should be a waterproof and windproof fabric that is also breathable, allowing moisture to escape to the outside.

The layering principle is relevant for both summer and winter conditions, as layers are added or removed to adapt to the work-rate (and heat generation) while walking, and the external weather conditions experienced. Other items to be carried year-round are a warm hat and gloves, while in summer a wide-brimmed hat is essential to protect against the sun. In addition to the clothing worn on the day, it is advisable to carry a warm, lightweight fleece inside a waterproof bag in the rucksack.

Choice of footwear generally comes down to personal preference, but the mixed terrain encountered on these walks means that proper hillwalking boots rather than shoes or trainers are required. Assuming non-winter walking conditions apply, the boots should be reasonably flexible, waterproof with a bellowed tongue, have good ankle support but allow for enough movement over different gradients, and have a sole with grips that are thick enough for moving over rocky ground. To avoid blisters, new boots should be ‘broken in’ gradually before being used on long walks.

Personal equipment should be carried in a well-fitting rucksack, with items that need to be kept dry stored in a waterproof liner, such as a plastic bin bag. Amongst the essential items to be carried on any of these walks are:

a survival bag

torch

whistle

map

compass

waterproof map case

first aid kit

mobile phone

pencil and paper

food and water

spare fleece.

Walking in larger groups or more testing conditions may also require a group shelter to be carried, but as with any walk, a balance should be struck between necessity and the weight of items carried. A particularly useful piece of equipment is adjustable walking poles, which can not only be used to reduce the strain on legs and knees while walking, but are also very handy for judging the conditions of soft and boggy terrain ahead.

Hillcraft

Despite being relatively low compared to the larger ranges in the Scottish Highlands, the hills covered in this guide present challenges that require similar levels of skills and experience – or ‘hillcraft’ – to those that would be needed in more mountainous regions. Typical characteristics such as high areas of featureless terrain, steep slopes and occasional large crags, will at times require confidence in personal ability, and good judgement.

Navigation

Competent navigation is the primary skill required for anyone wishing to enjoy safe hillwalking. While navigational skills will take time to master and maintain, familiarity with map reading undoubtedly helps in selecting walks, and enhances confidence, enjoyment and safety on the hills. The route descriptions in this guide assume a basic level of navigational understanding (detailed in the How to Use This Guide section). Courses, books and spending time on the hills with competent friends are all good ways to begin learning navigation.

Sickness and Injury

Common sense, planning and good navigation should mean most difficult situations on the hill are avoided. However, in situations where an individual hillwalker or a member of a hillwalking party are immobilised due to sickness or injury, some basic procedures will ensure circumstances do not get out of control.

Firstly, find some shelter in the immediate vicinity (which in these hills may be difficult). Even the most minimal cover from wind and rain, such as a peat hag or drystone dyke, will help.

Maintain body heat by adding any extra clothes and climbing inside a survival bag (and then the group shelter if one is available).

Treat medical conditions or injuries as well as you can using the first aid kit, considering these as an ongoing concern. Focus also on maintaining personal and group morale.

If a signal is available on a mobile phone, call for help from the Mountain Rescue services by first dialling 999 and asking for the police. Be ready to inform Mountain Rescue of your location, ideally by giving a six-figure grid reference. Mountain Rescue may also need to know details such as the number of walkers in the party, any medical conditions or injuries sustained, a description of the surrounding area, and the time and location at which the walk began. If no phone or signal is available, the above details should be written down and given to the most able person if they are in a position to seek help. The importance of leaving a route card is obvious (in particular for the individual walker) when emergency situations arise.

Once help has been requested it is important to stay at the exact location. Signal for help using the recognised rescue code of six long blasts with a whistle and/or six flashes of a torch every minute, listening out for three whistles or flashes as a response from the rescuers. Continue using the code until you have been reached by Mountain Rescue.

First Aid

An appropriate first aid kit and a basic knowledge of first aid will help to relieve some uncomfortable minor injuries. Blisters are perhaps the most common problem experienced by hillwalkers, but can be avoided by wearing well-fitting boots that have been broken in over a period of time. If blisters occur it is best to treat them as soon as possible. In the early stages of a blister, applying Vaseline will help reduce the friction that creates sore points on the soft tissue of the foot. Alternatively, rather than bursting any swelling it is preferable to simply cover the blister with a plaster or other dressing to avoid further rubbing.

Other common complaints such as sprains are also largely preventable with appropriate footwear and careful placement of the feet while walking. Inevitably, when sprains do occur they are painful, and severely restrict the pace of walking, so providing support to the injured area by snugly binding it with gaffer tape (carried in the first aid kit or taped around a walking pole) is often the ideal treatment. Walking poles are extremely useful in relieving pressure on sprains and twists.

Less preventable and more difficult to deal with, fractures are often the result of falls or slips. Fractures to the legs or ankles will almost certainly require rescue assistance, while fractures to the arms or wrists may well be supported by creating a sling from a triangular bandage kept in the first aid kit, or by improvising with an item of clothing.

Perhaps the most serious medical conditions to be aware of result from environmental factors affecting the body's core temperature. Walkers who are unprepared for the effects of heat loss, due to inadequate clothing or a lack of equipment to cope with an enforced stop, may quickly become susceptible to hypothermia. The very serious effects of hypothermia are felt in a relatively short space of time and are initially hard to recognise. Feelings of fatigue, listlessness and irritability are some of the vague symptoms common at the onset of ‘exposure’, which if not spotted early on can quickly spiral into the later stages of hypothermia. Thankfully, good planning and preparation should eliminate most circumstances where hypothermia may arise.

Walkers on Andrew Gannel Hill with King's Seat in the background (Walks 11 and 20)

As with hypothermia, heat exhaustion is also easily preventable, but if left untreated can also lead to more serious conditions. Heat exhaustion occurs gradually due to a loss of water and salts from the body as a result of vigorous exercise in warm, still temperatures. The body becomes less able to dissipate heat effectively, leading to feelings of fatigue, light-headedness and muscle cramps. Heat exhaustion is best prevented by a regular intake of liquid and by regulating body temperature while walking. However, at the first symptoms the walker should seek shade and rest, take on board fluids, and eat sweet and salty foods.

The effects of sunburn should also be prevented on hot days by covering exposed skin with clothing or sunscreen, which should always be carried in the first aid kit in the summer months. Other recommended items in the first aid kit may include:

crepe bandages

lint dressing

triangular bandage

plasters

blister kit

wound closure strips

saline wash

disposable gloves

antiseptic wipes

gaffer tape

scissors

emergency high-energy food.

Access and the Environment

Most land in Scotland and the areas covered in this guide is privately owned. The long-standing tradition of freedom of access to the hills in Scotland was formalised through legislation in February 2005, giving hillwalkers statutory rights of responsible access within the guidelines of the Scottish Outdoor Access Code.

SCOTTISH OUTDOOR ACCESS CODE

The main points of the code relevant to responsible hillwalking are summarised below.

Take personal responsibility for your own actions.

Respect people's privacy and peace of mind.

Help land managers and others to work safely and effectively.

Care for your environment.

Keep your dog under proper control.

The guidelines of the code should translate into responsible action, with an awareness of the particular environment walkers find themselves in.

Some specific advice that hillwalkers should consider for the areas covered in this guide is as follows.

Minimising disturbance to sheep, especially during lambing season (March–May). Dogs should be kept on leads at all times near sheep and efforts should always be made not to unduly upset them.

Carry a plastic bag in your pocket to collect any litter you see. Don't just take your own litter home with you; walking past the litter left by the ignorant few is almost as bad as dropping it in the first place.

Be aware of the grouse-shooting season (12 August – 10 December). Also be aware of work carried out near farms and on forestry tracks, observing any reasonable request from land managers. It is respectful to ask permission to use the land if the landowner is met, and they will often be able to give you good advice on areas to avoid or good routes.

A lot of the routes in this guide cross fences. Wherever possible use the stiles provided or walk around fences. If a fence does need to be crossed, avoid applying weight to the fence, in particular by taking off heavy packs before crossing.

Stick to paths when possible, keeping to the middle of the path to avoid further widening it.

Minimise the environmental impact of your walking by using public transport or one car for transporting several friends to the start of a route.

Do not disturb wildlife or the environment by picking plants/flowers or interfering with the habitats of birds and animals.