Читать книгу Say Nothing: A True Story Of Murder and Memory In Northern Ireland - Patrick Keefe Radden - Страница 24

Оглавление9

Orphans

One day in January 1973, a television crew from the BBC arrived at St Jude’s Walk. They were looking for the McConville children. Jean had been gone for more than a month. The local press had become aware of the story after an initial article was published in the newsletter of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association. Under the headline WHERE IS JEAN MCCONVILLE, the article described how the widowed mother of ten had been missing since 7 December, ‘when she was unceremoniously removed from her home’. Picking up on that original item, the Belfast Telegraph ran a short article on 16 January, ‘SNATCHED MOTHER MISSING A MONTH’, which noted that none of the children had reported the abduction of their mother to the police. The next day, the paper appealed for help in solving the ‘mystery disappearance’.

The BBC crew discovered Helen and the younger children living alone in the flat. After the cameras had been set up, the children sat huddled on the sofa, framed by a backdrop of striped yellow wallpaper, and described their ordeal. ‘Four young girls come into the kitchen. They ordered all the kids up the stairs and they just walked in and took my mummy,’ Agnes said quietly. ‘Mummy walked out in the hall, she put on her coat and left.’

‘What did your mummy say when she left?’ the interviewer asked.

‘She had a big squeal,’ Agnes said.

‘Do you know why your mummy was taken away?’

They didn’t. Helen was a lovely-looking teenager, with the same pale and narrow face as her mother, her dark hair swept to either side. She sat with Billy on her lap and nervously averted her eyes from the camera. The boys were fair and ginger. Tucker was sitting on Agnes’s lap, wearing a blue turtleneck and shorts, though it was the dead of winter, revealing his knobbly knees. The kids were twitchy, their eyes roving all over the place. Michael sat to Helen’s side, nearly cut out of the shot. He stared at the camera, blinking.

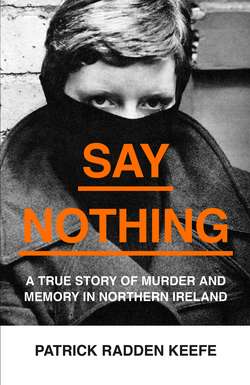

Michael, Helen, Billy, Jim, Agnes and Tucker McConville (Still from BBC Northern Ireland news footage, January 1973)

‘Helen, I believe you’re looking after the family,’ the reporter said. ‘How are you managing to cope?’

‘Okay.’

‘When do you think you’ll see your mummy again?’

‘Don’t know.’

‘Nobody’s been in touch with you at all?’

Agnes mentioned that they had seen Granny McConville.

‘She must be a fairly old lady by now,’ the reporter said.

‘She’s blind,’ Agnes said. Agnes was thirteen. She noted, hopefully, that her mother had been wearing red slippers when she was taken away. It was like an image from a fairy tale. A clue. Agnes said that the siblings would ‘keep our fingers crossed and pray hard for her to come back’.

Granny McConville may have been part of the reason that the children had not reported Jean’s disappearance to the police. She told people that she was afraid to, though she did not spell out precisely why. The children believed, fervently, that their mother would soon come home. But things began to look bleak. They were able to draw on Jean’s pension. But where one might expect the close-knit community in Belfast to rally around and care for such a family, dropping by with a hot meal or assisting Helen with the children, nobody did. Instead, it was as if the whole community in Divis simply chose to ignore the flatful of abandoned children on St Jude’s Walk. It might simply have been that this was a time of crisis in Belfast and people had worries of their own, or there could have been some darker reason. But in any case, nearly everyone in the community simply looked the other way.

A social worker did visit the children not long after Jean was taken. The authorities had received a call about a pack of siblings who had been looking after themselves. A bureaucrat created a new file and indicated that the children’s mother appeared to have been abducted by ‘an organisation’ – shorthand for a paramilitary group. The social worker spoke with Granny McConville, who did not seem overly perturbed. According to notes from the meeting, Jean’s mother-in-law asserted, primly, that Helen was ‘a very capable girl’ and seemed to be managing with the children. Helen did not get along with Granny McConville any more than Jean had. ‘No fondness there,’ the social worker wrote.

This was not exactly a healthy environment for young children, and the social worker recommended putting them into care – turning them over to the state, to be brought up at a group home. But the McConville children flatly refused. Their mother would be returning any day now, they explained. They needed to be at home when she got back.

They held on to one another, marooned inside the flat. Bedtime was suspended and dishes piled up in the sink. The neighbours, rather than help, started to complain to the authorities that they couldn’t sleep at night because the children were making so much noise, with nobody to supervise them, and you could hear the racket through the walls. Even the Catholic Church declined to intervene. One report from the social worker, just a week before Christmas, noted that a local parish priest was aware of the children’s predicament but was ‘unsympathetic’. As other local children were composing Christmas lists, the McConvilles were running out of food. They didn’t have much money coming in. Only Archie, who worked as an apprentice roof tiler, had a job. The children started getting into trouble. Michael would stay out late and shoplift food. Eventually he was caught, along with one of his brothers, stealing chocolate biscuits from a shop in town. Asked by the police why he had done it, he said that he and his siblings had not eaten in several days. They were starving. Michael was eleven years old. When the authorities questioned the McConville kids about their parents, Jim told them, ‘My daddy is dead and the IRA took my mummy away.’

There is no record in the files of the Royal Ulster Constabulary of any investigation into the disappearance of Jean McConville. She was abducted at the end of the most violent year of the conflict, and this sort of incident, horrible though it was, may not have risen to such a level that the police felt the need to concern themselves. A detective from Springfield Road police station did stop by the flat on 17 January, but the police were not able to offer any substantive clues and do not appear to have pursued the matter. Two local Members of Parliament, when they discovered what had happened, decried the kidnapping as ‘a callous act’ and appealed for help in finding Jean. But nobody came forward with information.

Belfast could sometimes feel more like a small town than a city. Even before the Troubles, the civic culture of the place was clotted with unsubstantiated gossip. Almost as soon as Jean McConville had disappeared, rumours began to circulate that she had not been kidnapped at all – that, on the contrary, she had absconded of her own free will, abandoning her children to shack up with a British soldier. The children, who were already seized with worry, became aware of these stories. They would hear people whispering, feel the hot glare of judgement when they saw their neighbours in the shop or on the street. Back at the flat, some of them would wonder aloud if it could be true. Could she really have left them? It didn’t seem possible. But how else to explain the fact that she had not returned? Archie McConville would later conclude that all that pernicious whispering amounted to more than just salt in the wound. It was a kind of poison, he decided, ‘an attempt to wreck our minds’.

One by-product of the Troubles was a culture of silence. With armed factions at war in the streets, an act as innocent as making enquiries about a vanished loved one could be dangerous. One day that February, a posse of boys from the youth wing of the IRA seized Michael McConville. They took him to a room where they tied him up and stabbed him in the leg with a penknife. They let him go with a warning: Don’t talk to anyone about what happened to your mother.

The interlude of freedom did not last. By February, social services had initiated the process of relocating the children to orphanages. One day, three women turned up at the flat and declared that they had been granted tenancy and were ready to move in. This was happening all the time in Belfast, a cruel expediency of wartime. It was like an awful game of musical chairs: no sooner was one family uprooted than another uprooted family would take their home. The children refused to leave. But the state had decided, and ultimately the kids were made wards of court.

The act of disappearing someone, which the International Criminal Court would eventually classify as a crime against humanity, is so pernicious, in part, because it can leave the loved ones of the victim in a purgatory of uncertainty. The children held out hope that they had not been orphaned, and that their mother might suddenly reappear. Perhaps she had developed amnesia and was living in another country, unaware that she had left a whole life behind in Belfast.

But, even then, there was reason to believe that something terrible had happened to Jean McConville. About a week after she was kidnapped, a young man whom the children did not know had come to the door of the flat and handed them their mother’s purse and three rings she had been wearing when she left: her engagement ring, her wedding ring, and an eternity ring that Arthur had given her. Desperate for information, the children asked where Jean was. ‘I don’t know anything about your mother,’ the man said. ‘I was just told to give you these.’

Years later, Michael McConville would look back and isolate that encounter as the moment he realised that his mother must be dead.