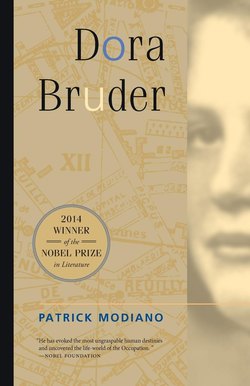

Читать книгу Dora Bruder - Patrick Modiano - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление.................

IN 1924, ERNEST BRUDER MARRIED A YOUNG WOMAN OF seventeen, Cécile Burdej, born 17 April 1907 in Budapest. I don’t know where this marriage took place, nor do I know the names of their witnesses. How did they happen to meet? Cécile Burdej had arrived in Paris the year before, with her parents, her brother, and her four sisters. A Jewish family of Russian origin, they had probably settled in Budapest at the beginning of the century.

Life in Budapest and Vienna being equally hard after the First World War, they had had to flee west yet again. They ended up in Paris, at the Jewish refuge in the Rue Lamarck. Within a month of their arrival, three of the girls, aged fourteen, twelve, and ten, were dead of typhoid fever.

Were Cécile and Ernest Bruder already living in the Avenue Liégeard, Sevran, at the time of their marriage? Or in a hotel in Paris? For the first years of their marriage, after Dora’s birth, they always lived in hotel rooms.

They are the sort of people who leave few traces. Virtually anonymous. Inseparable from those Paris streets, those suburban landscapes where, by chance, I discovered that they had lived. Often, what I know about them amounts to no more than a simple address. And such topographical precision contrasts with what we shall never know about their life—this blank, this mute block of the unknown.

I tracked down Ernest and Cécile Bruder’s niece. I talked to her on the telephone. The memories that she retains of them are those of childhood, at once fuzzy and sharp. She remembers her uncle’s gentleness, his kindness. It was she who gave me the few details that I have noted down about their family. She had heard it said that before they lived in the hotel on the Boulevard Ornano, Ernest, Cécile, and their daughter, Dora, had lived in another hotel. In a street off the Rue des Poissonniers. Looking at the street map, I read her out a succession of names. Yes, that was it, the Rue Polonceau. But she had never heard any mention of Sevran, nor Freinville, nor the Westinghouse factory.

It is said that premises retain some stamp, however faint, of their previous inhabitants. Stamp: an imprint, hollow or in relief. Hollow, I should say, in the case of Ernest and Cécile Bruder, of Dora. I have a sense of absence, of emptiness, whenever I find myself in a place where they have lived.

Two hotels, for that date, in the Rue Polonceau: the tenant of one, at number 49, was called Roquette. In the telephone directory he appears under Hôtel Vin. The other, at number 32, was owned by a Charles Campazzi. As hotels, they had a bad reputation. Today, they no longer exist.

Often, around 1968, I would follow the boulevards as far as the arches of the overhead métro. My starting point was the Place Blanche. In December, a traveling fair occupied the open ground. Its lights grew dimmer the nearer you got to the Boulevard de la Chapelle. At the time, I knew nothing of Dora Bruder and her parents. I remember that I had a peculiar sensation as I hugged the wall of Lariboisière Hospital, and again on crossing the railway tracks, as though I had penetrated the darkest part of Paris. But it was merely the contrast, after the dazzling lights of the Boulevard de Clichy, with the black, interminable wall, the penumbra beneath the métro arches . . .

Nowadays, on account of the railway lines, the proximity of the Gare du Nord and the rattle of the high-speed trains overhead, I still think of this part of the Boulevard de la Chapelle as a network of escape routes . . . A place where nobody would stay for long. A crossroads, where everybody went their separate ways to the four points of the compass.

All the same, I made a note of local schools where, if they still exist, I might find Dora Bruder’s name in the register:

Nursery school: 3 Rue Saint-Luc

Primary schools for girls: 11 Rue Cavé, 43 Rue des Poissonniers, Impasse d’Oran