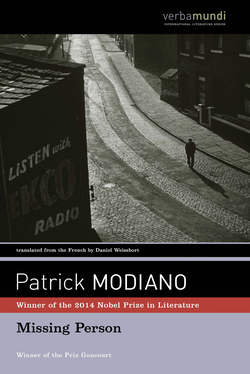

Читать книгу Missing Person - Patrick Modiano - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4

ОглавлениеIT WAS NOT very hard to follow him: he drove slowly. At the Porte Maillot, he ran a red light and the taxi driver did not dare follow suit, but we caught up with him again at Boulevard Maurice-Barrès. Our two cars pulled up side by side at a crosswalk. He glanced across at me absentmindedly, as motorists do when they find themselves side by side in a traffic jam.

He parked his car on Boulevard Richard-Wallace, in front of the apartment buildings at the end, near the Pont de Puteaux and the Seine. He started down Rue Julien-Potin and I paid off my taxi.

“Good luck, sir,” said the driver. “Be careful . . .”

And I felt his eyes following me as I too started down Rue Julien-Potin. Perhaps he thought I was in some danger.

Night was falling. A narrow road, lined by impersonal apartment buildings, built between the wars, which formed a single long façade, on each side and all the way along Rue Julien-Potin. Styoppa was ten yards ahead of me. He turned right into Rue Ernest-Deloison, and entered a grocery store.

The moment had come to approach him. But because of my shyness it was extremely hard for me, and I was afraid he would take me for a madman: I would stammer, my speech would become incoherent. Unless he recognized me at once, in which case I would let him do the talking.

He was coming out of the grocer’s shop, holding a paper bag.

“Mr. Styoppa de Dzhagorev?”

He looked very surprised. Our heads were on the same level, which intimidated me even more.

“Yes. But who are you?”

No, he did not recognize me. He spoke French without an accent. I had to screw up my courage.

“I . . . I’ve been meaning to contact you for . . . a long time . . .”

“What for?”

“I am writing . . . writing a book about the Emigration . . . I . . .”

“Are you Russian?”

It was the second time I had been asked this question. The taxi driver too had asked me. And, actually, perhaps I had been Russian.

“No.”

“And you’re interested in the Emigration?”

“I . . . I . . . I’m writing a book about the Emigration. Some . . . someone suggested I come to see you . . . Paul Sonachidze . . .”

“Sonachidze? . . .”

He pronounced the name in the Russian way. It was very soft, like wind rustling in the trees.

“A Georgian name . . . I don’t know it . . .”

He frowned.

“Sonachidze . . . no . . .”

“I don’t want to be a nuisance. If I could just ask you a few questions.”

“I’d be happy to answer them . . .”

He smiled a sad smile.

“A tragic tale, the Emigration . . . But how is it you call me Styoppa? . . .”

“I . . . don’t . . . I . . .”

“Most of those who called me Styoppa are dead. The others, you can count on the fingers of one hand.”

“It was . . . Sonachidze . . .”

“I don’t know him.”

“Can I . . . ask . . . you . . . a few questions?”

“Yes. Would you like to come up to my place? We can talk.”

In Rue Julien-Potin, after we had passed through a gateway, we crossed an open space surrounded by apartment buildings. We took a wooden elevator with a double latticework gate and, because of our height and the restricted space in the elevator, we had to bow our heads and keep them turned toward the wall, so we didn’t knock brows.

He lived on the fifth floor in a two-room flat. He showed me into the bedroom and stretched out on the bed.

“Forgive me,” he said, “but the ceiling is too low. It’s suffocating to stand.”

Indeed, there were only a few inches between the ceiling and the top of my head and I had to stoop. Furthermore, both he and I were a head too tall to clear the frame of the door leading into the other room and I imagined that he had often bumped his forehead there.

“You can stretch out too . . . if you wish . . .” He pointed to a small couch, upholstered in pale blue velvet, near the window.

“Make yourself at home . . . you’ll be much more comfortable lying down . . . Even if you sit, you feel cooped up here . . . Please, do lie down . . .”

I did so.

He had switched on a lamp with a salmon-pink shade, which was standing on his bedside table, and it gave out a soft light and cast shadows on the ceiling.

“So, you’re interested in the Emigration?”

“Very.”

“And yet, you’re still young . . .”

Young? I had never thought of myself as young. A large mirror in a gold frame hung on the wall, close to me. I looked at my face. Young?

“Oh . . . not so young as all that . . .”

There was a moment’s silence. The two of us, stretched out on either side of the room, looked like opium smokers.

“I’ve just returned from a funeral,” he said. “It’s a pity you didn’t meet the old lady who died . . . She could have told you many things . . . She was one of the real personalities of the Emigration . . .”

“Really?”

“A very brave woman. At the beginning, she opened a small tea-room, in Rue du Mont-Thabor, and she helped everybody . . . It was very hard . . .”

He sat up on the edge of the bed, his back bowed, arms crossed.

“I was fifteen at the time . . . When I think, there are not many left . . .”

“There’s . . . Georges Sacher . . .,” I said at random.

“Not for much longer. Do you know him?”

Was it the old gentleman of plaster? Or the fat bald-head with the Mongolian features?

“Look,” he said, “I can’t go over all these things again . . . It makes me too sad . . . But I can show you some photographs . . . The names and dates are there on the back . . . You’ll manage on your own . . .”

“It’s very kind of you to take so much trouble.”

He smiled at me.

“I’ve got lots of photos . . . I wrote the names and dates on the back, because one forgets everything . . .”

He stood up and, stooping, went into the next room.

I heard him open a drawer. He returned, a large red box in his hand, sat down on the floor and leaned his back against the edge of the bed.

“Come and sit down beside me. It will be easier to look at the photographs.”

I did so. A confectioner’s name was printed in gothic lettering on the lid of the box. He opened it. It was full of photos.

“In here you have the principal figures of the Emigration,” he said.

He handed me the photographs one by one, telling me the names and dates he read on the back: it was a litany, to which the Russian names lent a particular resonance, now explosive like cymbals clashing, now plaintive or almost mute. Trubetskoy. Orbelyani. Sheremetev. Galitsyn. Eristov. Obolensky. Bagration. Chavchavadze . . . Now and then, he took a photo back and consulted the name and date again. Some occasion. The Grand Duke Boris’s table at a gala ball at the Château-Basque, long after the Revolution. And this garland of faces on a photograph taken at a “black and white” dinner party, in 1914 . . . A class photograph of the Alexander Lycée in Petersburg.

“My older brother . . .”

He handed me the photos more and more quickly, no longer even looking at them. Evidently, he was anxious to have done with it. Suddenly I halted at one of them, printed on heavier paper than the others, and with no explanation on the back.

“What is it?” he asked me. “Something puzzling you?”

In the foreground, an old man, stiff and smiling, seated in an armchair. Behind him, a blonde young woman with very limpid eyes. All around, small groups of people, most of whom had their backs to the camera. And toward the left, his right arm cut off by the edge of the picture, his hand on the shoulder of the blonde young woman, an extremely tall man, in a broken check lounge suit, about thirty years old, with dark hair and a thin moustache. I was convinced it was me.

I drew closer to him. Our backs leaned against the edge of the bed, our legs were stretched out on the floor, our shoulders touched.

“Tell me, who are those people?” I asked him.

He took the photograph and looked at it wearily.

“That one was Giorgiadze . . .”

He pointed to the old man, seated in the armchair.

“He was at the Georgian Consulate in Paris, up to the time . . .”

He did not finish his sentence, as though its conclusion must be obvious to me.

“That one was his grand-daughter . . . Her name was Gay . . . Gay Orlov. She emigrated to America with her parents . . .”

“Did you know her?”

“Not very well. No. She stayed on in America a long time.”

“And what about him?” I asked in a toneless voice, pointing to myself in the photo.

“Him?”

He knitted his brows.

“I don’t know who he is.”

“Really?”

“No.”

I sighed deeply.

“Don’t you think he looks like me?”

He looked at me.

“Looks like you? No. Why?”

“Nothing.”

He handed me another photograph.

It was a picture of a little girl in a white dress, with long fair hair, at a seaside resort, since one could see beach-huts and a section of beach and sea. “Mara Orlov – Yalta” was written in purple ink, on the back.

“There, you see . . . the same girl . . . Gay Orlov . . . Her name was Mara . . . She didn’t yet have an American first name . . .”

And he pointed to the blonde young woman in the other photo which I was still holding.

“My mother kept all these things . . .”

He rose abruptly.

“Do you mind if we stop now? My head is spinning . . .”

He passed a hand over his brow.

“I’ll go and change . . . If you like, we can have dinner together . . .”

I remained alone, sitting on the floor, the photos scattered about me. I stacked them in the large red box and kept only two, which I put on the bed: the photo in which I appeared, next to Gay Orlov and the old man, Giorgiadze, and the one of Gay Orlov as a child at Yalta. I rose and went to the window.

It was night. The window looked out on to another open space with buildings round it. At the far end, the Seine, and to the left, the Pont de Puteaux. And the Île, stretching out. Lines of cars were crossing the bridge. I gazed at the façades of the buildings, all the windows lit up, just like the window at which I was standing. And in this labyrinthine maze of buildings, staircases and elevators, among these hundreds of cubbyholes, I had found a man who perhaps . . .

I had pressed my brow against the window. Below, each building entrance was lit by a yellow light which would burn all night.

“The restaurant is quite close,” he said.

I took the two photos I had left on the bed.

“Mr. de Dzhagorev,” I said, “would you be so kind as to lend me these two photos?”

“You can keep them.”

He pointed to the red box.

“You can keep all the photos.”

“But . . . I . . .”

“Take them.”

His tone was so peremptory that it was impossible to argue. When we left the apartment, I was carrying the large box under my arm.

At street level, we proceeded along the Quai du Général-Kœnig.

We descended some stone steps, and there, right by the side of the Seine, was a brick building. Above the door, a sign: “Bar-Restaurant de l’Île.” We went in. A low-ceilinged room, and tables with white paper napkins and wicker chairs. Through the windows one could see the Seine and the lights of the Pont de Puteaux. We sat down at the back of the room. We were the only customers.

Styoppa groped in his pocket and placed in the center of the table the package I had seen him buy at the grocer’s.

“The usual?” asked the waiter.

“The usual.”

“And you, sir?” asked the waiter, turning to me.

“This gentleman will have the same as me.”

Very swiftly the waiter brought us two servings of Baltic herring and poured some mineral water into two thimble-sized glasses. Styoppa extracted some cucumbers from the package in the center of the table and we shared them.

“Is this all right for you?” he asked me.

“Do you really not wish to keep all these souvenirs?” I asked him.

“No. They’re yours now. I’m passing on the torch.”

We ate in silence. A boat passed, so close, that I had time to see its occupants, framed in the window, sitting at a table and eating, just like us.

“And this . . . Gay Orlov?” I said. “Do you know what became of her?”

“Gay Orlov? I believe she’s dead.”

“Dead?”

“I believe so. I must have met her two or three times. I hardly knew her . . . It was my mother who was a friend of old Giorgiadze. A little cucumber?”

“Thanks.”

“I think she led a very restless life in America . . .”

“And you don’t know anyone who could give me any information about this . . . Gay Orlov?”

He threw me a compassionate look.

“My poor friend . . . no one . . . Perhaps there’s someone in America . . .”

Another boat passed, black, slow, as though abandoned.

“I always have a banana for dessert,” he said. “What would you like?”

“I’ll have one too.”

We ate our bananas.

“And this Gay Orlov’s . . . parents?” I asked.

“They must have died in America. One dies everywhere, you know . . .”

“Did Giorgiadze have any other relatives in France?”

He shrugged his shoulders.

“But why are you so concerned about Gay Orlov? Was she your sister?”

He smiled pleasantly.

“Some coffee?” he asked.

“No, thanks.”

“I won’t either.”

He wanted to pay the bill, but I forestalled him. We left the restaurant “de l’Île” and he took my arm as we climbed the steps of the quay. A fog had come up, soft but with an icy feel to it. It filled your lungs with such cold that you felt you were floating on air. On the quay again, I could barely make out the buildings a few yards off.

I guided him, as if he were a blind man, to his apartment building, with the staircase entrances yellow blotches in the fog, the only reference points. He clasped my hand.

“Try to find Gay Orlov even so,” he said. “Since it means so much to you . . .”

I watched him entering the lighted entrance hall. He stopped and waved to me. I stood, motionless, the large red box under my arms, like a child returning from a birthday party, and I felt certain at that moment that he was saying something else to me but that the fog was muffling the sound of his voice.