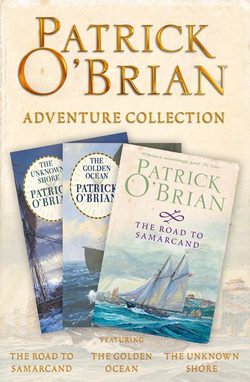

Читать книгу Patrick O’Brian 3-Book Adventure Collection: The Road to Samarcand, The Golden Ocean, The Unknown Shore - Patrick O’Brian - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Nine

ОглавлениеThrough the bleak lands beyond the great marshes the column pursued its steady road. Day after day they went straight over the high steppe or the half-desert where the cold sand blew perpetually over the dun earth: they no longer dug in the minor sites that the Professor had marked, and although he said that there were still three or four places where they must certainly stop, he said it without conviction. He was in a ferment about the jade, and his chief wish was to get it safely back to the museum: he carried the pick of the collection about his person, and the rest he confided to Li Han, who sewed the pieces into his quilted cotton clothes and walked about as though he were treading on eggs. The Professor had already begun a rough catalogue of the jades, and every night the lamp burnt until after midnight in his yurt. He said, ‘Our aim must now be to reach Samarcand as early as possible: fortunately, the worst of our journey is over, and we have only the Takla Makan to traverse or to circumvent, and then, I understand, the rest of the road is comparatively simple.’

‘Only the Takla Makan!’ exclaimed Sullivan, thinking of that howling desert. ‘Only the Takla Makan.’ But seeing the Professor’s anxious face he added, ‘Yes, you are quite right. Once we have got that behind us, the rest should not be too difficult.’

When he was alone with Ross he said, ‘Are they still there?’

‘I saw them at break of day,’ said Ross, ‘but I have not seen them since. It may be that we are wrong – growing over-anxious and seeing boggles behind every door, like bairns.’

‘I hope so,’ replied Sullivan, scanning the horizon. Ever since they had left the swamps he had had the impression that they were being followed. Sometimes it was a group of horsemen who kept so far away that they might have been antelopes or the tall wild asses of the steppe, and sometimes it was a single rider; but Sullivan and Ross had powerful glasses, and the form that might have been a distant antelope to a naked eye showed up as a Tartar in the binoculars, a Tartar with the head-dress and the lance of a Kazak.

Yet when some days later they met with the immense herds of the Churungdzai and camped for the night with the tribesmen, they heard nothing of the Kazaks; they felt that their suspicions had been mistaken, and they were glad that they had not mentioned them to the others. The Churungdzai were a tribe related to the Kokonor horde: they were as friendly as could be, and they gave news of Hulagu Khan. He was a week’s journey to the north, on the edge of the Takla Makan, and they thought that he might come south to cut their route near the place called the Kirgiz Tomb.

It took them nearly the whole of the next day to pass through the innumerable herds of the Churungdzai, although they were but a tenth part of the tribe’s wealth, but by the evening they were alone on the steppe again, and in the days that followed, the old, calm routine settled down as though there had been no change.

Derrick had traded some ammunition for a hawking eagle with one of the Churungdzai, and with the great bird on his arm he rode out with Chingiz to see what they could find for the pot. The eagle was big enough to strike down an antelope, and Derrick, at intervals of working out the problem in trigonometry that Ross had set him for his morning’s task, had thought that he had seen some on the far edge of the sky.

‘You must ride with your right arm across your saddle-bow,’ said Chingiz, and Derrick quickly realised that he was right. He had been trying to imitate the Mongol’s way of carrying his falcon with his arm free at his side, and each time that his arm had moved under the much greater weight of the eagle, the huge talons had gripped his muscles through the thick glove that he wore as the hooded eagle stirred to keep its balance.

They had gone almost out of sight of their caravan, and Derrick was riding more easily, when they heard the drumming of horse’s hooves: it was Sullivan, coming up fast to join them.

‘I thought I would come and see how your new purchase behaves,’ he said, drawing alongside. ‘Is it any good, Chingiz?’

‘I hope so,’ said Chingiz, looking at the eagle with his beady eyes narrowed still further. ‘But it is very small.’

‘Small!’ cried Derrick, thinking of the steely grip of those talons, and how they had gripped him to the bone when the bird was merely sitting there, with no intention of doing harm. ‘Small! What do you think we are going to hunt? Elephants?’

‘My father has an eagle twice that size,’ said Chingiz, stroking his little peregrine.

‘Yes,’ said Sullivan, ‘but your father is a Khan, and drinks the milk of white mares. Naturally he has a larger eagle than anybody else.’

‘And my ancestor,’ said Chingiz, who was not altogether pleased about Derrick’s eagle, ‘had one four times the size of my father’s.’

‘That must have been difficult to carry,’ observed Derrick.

‘Not for my ancestor,’ replied Chingiz, firmly. ‘He had two on each arm.’

Derrick was about to say something, but he checked himself. He had learnt by now that if he pulled Chingiz’s leg the results were likely to be rapid and bloody.

‘Did your ancestor ever have any trouble with the Kazaks?’ asked Sullivan.

‘No,’ said Chingiz. ‘He built a tower of ten thousand Kazak skulls – Maiman Kazaks, they were – and then he never had any trouble with them at all.’

‘Ten thousand?’ asked Derrick.

‘Yes,’ said Chingiz, ‘ten thousand. You will see them when we come to the rocky country soon: they are still there, at the place called the Kazak Tomb.’

Sullivan nodded. He had seen it.

Suddenly Chingiz shouted, ‘Loose, loose, loose!’ While they had been talking an antelope had sprung up out of a single patch of shade, and now it was flying towards the horizon. Derrick tore at the jesses, the leather thongs that held the eagle to his arm, but he was unhandy with his left hand, and his pony was too excited to stand.

‘Cast off,’ cried Sullivan. ‘Look alive, boy.’

Chang barked, the pony shied, and it was minutes before Derrick had the eagle in the air. By this time the antelope was no more than a swiftly-moving mist of flying sand.

The eagle towered, its huge wings making a bar of shadow over them, and circled high, with its wing-tips flaring in the wind. It seemed to take some time to make up its mind, and they could see its head turned from side to side as it scanned the plain; but then, with no perceptible movement of its wings, it began to travel down the sky, faster and faster, as if it were sliding down an oiled groove. They galloped at full stretch below it, with their reins loose and their horses racing at the height of their speed, but it left them as if they were standing still. On and on it went, growing smaller in the distance; then Derrick saw it mount again and stoop.

Chingiz was up first, but the eagle had already lifted, and it was floating easily in the sky. ‘Call him,’ Chingiz shouted to Derrick, and when Derrick had called the eagle without effect, the Mongol cried, ‘Lure him, lure him as fast as you can.’

Derrick unslung the lure from his saddle, a stuffed piece of felt on a short length of rope, and he whirled it in the air, calling still. The eagle looked, dropped twenty feet, hesitated and rose again.

‘He sees something,’ said Chingiz. ‘We must follow.’ He stopped for a moment to hoist the little antelope across his saddle-bow – the eagle had broken its back with one gripe of its claws – and they rode slowly after the towering eagle, calling and luring, but in vain.

They were so busy watching the bird that they did not see the men until they were quite near them. They were two, one mounted and watching the eagle, and the other looking at his horse’s hoof. They were fully armed, with slung rifles, curved swords hanging at the left side of their saddles, and in his right hand the mounted man held a lance.

Sullivan motioned Chingiz and Derrick to a halt and rode slowly forward.

‘Peace be with you,’ he said.

‘And on you be peace,’ replied the mounted man.

At this moment the eagle came down to Derrick’s arm, and he was too busy hooding it to catch what was being said. But when the bird was quietly on his arm again he heard the mounted man say, ‘Are you in the company of the idolaters?’

‘We are people of the Book also,’ answered Sullivan.

Derrick noticed that the dismounted man had his rifle unslung, and for a second he thought there was going to be trouble, but Sullivan swung his horse about, and saying over his shoulder, ‘A good journey and peace, in the Name of God,’ he rode back to them.

The Tartar’s deep reply, ‘In the Name of God, peace and a good journey,’ came over the sand, and each group rode away from the other.

Sullivan went on silently for some time, and although Derrick looked questioningly at him he said nothing until they were nearly up to the column.

‘They were Kazaks,’ he said in an off-hand tone. ‘They are Mohammedans, you know. They are probably on a journey. Can you tell what horde they belong to, Chingiz?’

‘They were not Kirei Kazaks,’ said Chingiz, ‘nor Uwak. They might have been from the Altai, though that is far away. But they were Kazaks, and they must have had my father’s permission to be here.

‘And yet,’ said Chingiz, as they rode up to the halted column, ‘if they were going on a journey, it is strange that they had no led horses. The Kazaks always lead two or three if they are far from home.’

Derrick thought it strange, too, but the camp was just forming, and as they hurried to the kitchen tent to deliver the antelope to Li Han, he forgot all about it.

Li Han was doling out a measure of rice to Timur, a lame, one-eyed, dog-faced Mongol to whom he had delegated nearly all the work of cooking for the past few weeks.

‘Come on, Li Han, you’ve got to do this yourself,’ cried Derrick, bringing in the antelope. Timur was an expert in loading camels, but his one idea of cooking was thin, rubbery strips of flesh, as nearly raw as possible.

‘That’s right,’ said Olaf, suddenly appearing from behind a mound of provisions. ‘You turn sea-cook again for a day, Li Han.’

Li Han sniffed, and turned to light the fire. The Professor had more and more entrusted him with duties as far from those of a sea-cook as could be imagined. For a long time now he had copied Chinese inscriptions and had arranged the Professor’s notes, taking endless pains and writing with beautiful neatness: he had thrown himself into it heart and soul, and all day long, as they rode, he was to be seen gazing into a book, in order, as he said, ‘to fit himself for service and society of august philosophical sage’. But all this, though it pleased the Professor, pleased nobody else. Both Derrick and Olaf regretted the days when Li Han would turn out a succulent dish at a moment’s notice. They reminded one another of the meals aboard the Wanderer, wonderful meals that came in rapid succession from the galley stove; and that evening, when the keen air and the long day’s march had given them a needle-sharp appetite, they looked forward eagerly to something very good indeed from the antelope.

But as they sat round the fire, Li Han appeared from the Professor’s tent, carrying a fresh sheaf of papers: he pointed to the iron pot and sat on a box, frowning over the written sheets. Olaf helped himself and stirred moodily in his dish: it contained an evil mess prepared by Timur by way of an experiment. The antelope was still untouched. Li Han sipped at his tea-bowl, staring thoughtfully into the distance.

‘You going to eat any of this duff, eh?’ growled Olaf.

‘By no means,’ replied Li Han. ‘Have already partaken of egg with learned Professor.’

‘Humph. Ay reckon you ought to try some of this stuff. What you say, Derrick, eh?’

‘It is horrible duff,’ said Derrick, offering a little to Chang, who refused it apologetically. ‘Why don’t you cook us some decent chop, Li Han?’

‘When engaged in learned pursuits, cannot bend mind to menial tasks.’

‘Don’t you like to eat good food yourself?’

‘For disciple of philosopher, preserved egg suffices. I no longer worship belly, as in former days of besotted ignorance.’

‘You ban getting too high-hat,’ said Olaf, angrily. ‘Who are you calling besotted ignorance, anyway? You mouldy son of a half-baked weevil, if you was in the Wanderer’s galley right now, Ay reckon we would wipe the dishes with you, eh, Derrick?’

‘Abusive language invariable mark of cultural backward person,’ said Li Han.

‘Relax, Li Han, and turn us out something we can eat. Look, there’s a nice clear fire, and there’s that antelope all ready at hand,’ said Derrick, persuasively.

‘Regret am otherwise engaged. Also, certain personal remarks add touch of obnoxious compulsion. Shall remain in vindictive immobility.’

There was a short silence, in which Olaf came to a slow boil. ‘Skavensk!’ he cried, suddenly throwing down his bowl and leaping to his feet. ‘Lookit here, you cook-boy, you cook us a meal right now, or Ay ban going to tie you up in a knot like you’ve never seen before.’

‘Steady, Olaf. You can’t beat him up: he’s too small.’

‘Well, is he going to sit there like a heathen image just because he’s small, eh? Too high-hat, he is, see? Besotted ignorance, eh? You heard what he said? Ay sure got a mind to turn him inside out. Maybe he’d look better that way.’

Derrick whistled softly, and Chang thrust his muzzle against his knee. ‘Listen, Chang,’ he said. ‘You grab a hold of Li Han and make mincemeat out of him. Seize him, Chang! Break him and tear him then. Bring me his liver and lights, Chang.’ Chang rumbled like thunder in his throat, waving his tail.

Li Han started up. ‘Physical violence is mark of barbarian mind,’ he said apprehensively. ‘I will dissociate self from distasteful brawlery.’

‘High-hat, eh?’ cried Olaf. ‘You dissociate yourself from that!’ Olaf swung the iron pot in a high arc. Li Han dodged, but too late. The mess came down squelch on top of his head and the pot slammed down over his ears. At this moment Chang joined in, leaping delightedly for the seat of Li Han’s trousers and roaring like a bloodhound.

Li Han sprawled into the fire, sprang out, spinning like a teetotum, and shrieked curses in a high-pitched yell. Derrick tripped him up and sat on his stomach. ‘You’d better pull the pot off, Olaf,’ he said, ‘it might be hot.’

‘Ay reckon we ought to leave it on for ever,’ said Olaf. ‘That ban a fine high hat, eh?’ Olaf had rarely made a joke of his own, and now he was so pleased with it that he could hardly stand for laughing.

When he could stop he pulled once or twice at the pot, but it was immovable. Muffled bellows came from Li Han.

‘Crack it, Olaf,’ said Derrick.

‘That won’t never crack. It’s iron, see?’

By now the bellowing from inside had assumed a pleading tone.

‘No. Ay reckon there’s nothing but a winch will ever unship this pot,’ said Olaf. ‘Or maybe a monkey wrench,’ he added thoughtfully.

‘I’ll hold him by the shoulders and you pull,’ said Derrick. ‘I think he’s drowning.’

‘Drowning a thousand miles from the nearest creek!’ exclaimed Olaf. ‘Cor stone the crows, that ban funny.’ He howled with laughter, but he grasped the pot again and heaved. But suddenly he changed his mind, rapped smartly on the sounding iron and hailed Li Han within, ‘Ahoy, Li Han. Will you cook if we let you out?’

‘Yes, yes. Me cookee top-chop one-time. Let out, plis,’ came the muffled voice, and Olaf heaved again. They pulled, grunting. Li Han shrieked like a stuck pig. Suddenly the pot came off with a loud plop: Olaf fell backwards into the fire, and Chang, charmed with the game, pinned Li Han to the ground, baying wildly.

Between them they made such an appalling din that they never heard the approaching thunder of the Mongols. The camp was filled with Kokonor tribesmen before Derrick could get up for laughing.

As they came in Hulagu and his brothers ran from the horse-lines, where they had been doctoring a sick mare. The leading tribesmen leapt from their horses, saluted Hulagu and spoke rapidly for a few moments. Hulagu ran to Sullivan’s yurt: in a minute he was out again, running for his horse, and before the dust of his going had settled down he was out of sight, together with his brother Kubilai and the other tribesmen.

Chingiz stood staring after them, fingering the dagger at his belt. ‘What’s the matter?’ asked Derrick.

‘The Altai Kazaks have come down from the north,’ replied Chingiz, with a savage grin. ‘They have come for their revenge for the tower of skulls, and they have joined with the Uruchang horde. They are raiding our yurts and killing whatever they can find. They have driven some of our herds into the Takla Makan, and they think they can destroy us, because my father is away. We are going to try to lead some of them into an ambush beyond the Kazak Tomb.’

Sullivan came quickly out of his tent and passed down the lines, giving his orders quietly and distinctly. An indescribable bustle filled the camp for half an hour, and then, out of the apparent confusion, a well-armed, well-mounted and well-prepared troop rode westward after Hulagu. Chingiz rode on Sullivan’s right hand to show the way, and once again Derrick was impressed by the way in which the Mongol seemed to carry a compass and a chart in his head. He was never at a loss, although the bare steppe seemed always the same, and as they rode fast through the gathering night he said that they were coming near to a single rock that stood out of the plain, and that there they were to stop. Hardly had he spoken when out of the dusk loomed the rock, straight ahead of them: he said that in the light of the dawn they would see broken country beyond, and that was to be their goal for the hour of the rising of the sun.

They lit no fire, for no light was to be seen, but they sat in a circle as though a fire had been there, and they ate their horse-flesh cold.

‘This is very instructive,’ said the Professor, as he wiped his lips. ‘As I understand it, the tribes beyond the Altai have been pushing the Kazaks to the south, and now the Kazaks in their turn are attacking our friends: it is surely a repetition of those great waves of barbarians who came one after the other to destroy the Roman Empire. And there are many other instances which will occur to you. One sees the evidence of these successive invasions so clearly in the excavation of any archaeological site, but to see the whole thing in present action is to have history brought to life in the most vivid manner – more vivid even than the most pronounced differentiation of the culture strata at, let us say, Beauplan’s classic excavation at Chrysopolis.’

‘I am sure you are right,’ said Sullivan, ‘but speaking as a layman, I must say that for my part it is a demonstration that I could do without. Living history has an awkward way of separating you from your head, and I would rather reach Samarcand all in one piece. For the moment I could wish that history would keep in its proper place – between the covers of a history book.’

By the time the eastern sky began to lighten they were in the saddle again, making their way towards a region of abrupt rocks and twisted ravines, a great stretch of country that seemed to have been torn apart by an almighty earthquake in the past.

Li Han took a gloomy view of the whole affair: he was riding behind, between Derrick and Olaf who kept near to him to pick him up when he fell, for although they had now traversed hundreds and hundreds of miles of Northern China, Inner and Outer Mongolia and Sinkiang on horseback, so that even Olaf could navigate his mare efficiently, Li Han had never become more than a most indifferent rider, and he was apt to pitch off on one side or the other whenever they went faster than a walk. ‘Surely,’ he gasped, clutching again at his horse’s mane, ‘surely peaceful negotiations will suffice? Soothing remarks and well-turned compliments will assuage the barbarians: or if not, a small present, accompanied by promises of more, will turn their wrath.’

‘These guys ban tough eggs,’ said Olaf. ‘They ain’t out for no parlour-conversation. Ay reckon the best kind of present ban one ounce of lead, right between the eyes, see?’

‘But suppose the barbarians should shoot first, with two ounces of lead? Or leap upon us with horrible cries?’ Li Han shuddered. ‘But doubtless,’ he added, to comfort himself, ‘philosophic Professor will dissuade both sides from actual blows at the last moment by honeyed words and sage-like example.’

‘Not at all, Li Han,’ cried Professor Ayrton, who had caught these last words, ‘I am all for blows in this emergency. If these invading Kazaks try to come between me and the Wu Ti jade, I shall endeavour to deal out the shrewdest and most painful blows that I can manage, with no honeyed words at all. You must remember the precept of Chih Hsü, “In a sudden encounter with a tiger, a double-edged sword of proved temper is of a greater material value than the polished manners of Chang-An.”’ He raised his voice, and speaking to Ross and Sullivan, he said, ‘I feel quite like the warhorse in Job. Have we much farther to go?’

‘A fair distance yet. Did you say a warhorse, Professor?’

‘Yes. “He saith among the trumpets Ha, ha; and he smelleth the battle afar off, the thunder of the captains, and the shouting.” I believe you people have corrupted me by your example: why, when I return to the museum, they will call me the Scourge of Bloomsbury.’

‘The Professor says that he feels like a warhorse,’ said Derrick to Chingiz.

‘Hum. Well, perhaps his learning will be of some use to us with spells and incantations.’

‘Don’t look now, Professor,’ said Ross, quietly, ‘but I think your principles are slipping.’

‘My principles? Oh, yes: I apprehend your meaning. But, my dear sir, do you not appreciate the difference between attack and defence? Here are we, in the middle of our good friends’ country, and we find them being annoyed, harassed and put to serious inconvenience by a pack of invading ruffians. Are we not to show our displeasure? Furthermore, Sullivan assured me that the Kazaks will undoubtedly associate us with the Kokonor horde, and that if they are not discouraged by firm action on our parts, they will certainly molest us, even to the point of taking away our belongings. And thirdly as the Kazaks are Mohammedans, and there is an element of religious fanaticism in their attack, they may, if victorious, go so far as to destroy the Wu Ti jades, many of which, I am glad to say, are graven images, and anathema to these bigots. All these things being considered, therefore – loyalty to our friends, a due regard for our own safety, and the preservation of these artistic treasures – I feel wholly justified in crying “Forward, with the greatest convenient speed, and smite them hip and thigh.”’

Chingiz pushed his horse up to Sullivan, and when the Professor had finished, he pointed. ‘There is the Kazak Tomb,’ he said. On a high rock before them there was a low, crumbling mound: once it had reached up in a steep-sided pyramid; the centuries had brought it down, but as they came nearer they could still see that the whole erection had been made of hundreds upon hundreds of skulls.

‘We will add to that before dawn,’ said Chingiz, ‘either with their heads or our own.’

Beyond the Kazak Tomb the way grew harder. On either hand the broken, weathered rocks leaned over their path: they rode in single file, picking their way with care. From the shadow of a great boulder came a single man, a Kokonor Mongol who was waiting for them. Down through a steep canyon he led them, and there the shadow of the night lingered still: they tethered their horses in a place where there was a thin sprinkling of grass, and began to climb. They came up into the light over a difficult shoulder of moving shale, and as the first red glow of the sunrise appeared they reached the skyline.

They were at the top of a cliff that overlooked a narrow valley, almost a ravine, with sheer sides: the valley led out into the distant plain, in the open country far beyond; but anyone who tried to pass through the tumbled ridge by this valley would find themselves brought up short by the perpendicular cliff at the hither end of it. The plan was that the Kazaks should be lured up this ravine to its very end, and that there they should be caught by rifle-fire from the heights.

They strung themselves out along the sides, finding good hiding-places among the boulders. They would have several hours to wait, but as it was impossible to say for certain when Hulagu and his men would lead their pursuers into the trap, they must remain hidden, silent and motionless for the whole of the long wait. When they had been there an hour Chang barked. ‘Put a strap round that dog’s muzzle,’ snapped Sullivan. Some minutes later there came a soft whistle, to which Chingiz replied, and they saw another group of Mongols creeping among the rocks on the other side, taking up places opposite to them.

The hours passed slowly, very slowly, and the sun crept up the sky. A wind blew up from the farther steppe: it increased in strength, and as it howled and whistled through the rocks and down the narrow gully, it became very difficult to listen for the sounds they hoped to hear.

Derrick was changing from one cramped position to another when he saw the heads of the three men to his left all whip round at the same moment; they were listening intently down the length of the ravine. He froze motionless, and he heard the crackle of many rifles, far away and whipped from them by the wind.

Sullivan nodded and winked his eye: at the same instant Derrick became aware of the Professor’s lanky form stretched out behind him and creeping towards Sullivan.

‘Forgive me, Sullivan,’ whispered the Professor, ‘if this is an inopportune moment – I should have thought of it before, but it slipped my mind. What I wished to say was that although I am conversant with the general principles underlying the use of firearms, I have never actually –’

‘Get down,’ hissed Ross, pulling the Professor off the skyline. ‘Here they come.’

Derrick flung himself flat and rammed home his bolt: he heard the same sharp, metallic sound to his right and his left. From where he lay he had a perfect view of the whole of the gulley, and he saw Kubilai and Hulagu with some twenty of their men coming into sight at the far end. Behind them came the Kazaks. It was difficult to see how many there were, because of the number of spare horses that galloped with them, but they were many; and as they raced nearer Derrick saw among them a white horse whose rider carried a lance with a yak’s tail flying like a pennant.

‘That is the son of the Altai Khan,’ murmured Chingiz, staring down his sights.

‘Quiet,’ whispered Sullivan. ‘Wait for it, wait for it.’

Now Hulagu and his men put on a great burst of speed: as they passed the silent watchers, Hulagu took the reins in his teeth, turned in his saddle and fired back. He scanned the rocks anxiously, and raced by.

The Kazak lances swept nearer and nearer, and above the wind came the thundering of their horses’ hooves. ‘Just a little closer,’ whispered Sullivan, cuddling the stock into his shoulder, ‘and you’re for it.’

A shot rang out behind them. The bullet spat rock six inches from Derrick’s heels, and the Professor said, ‘Dear me, it went off.’

The Kazaks pulled up in a cloud of dust. Ross and Chingiz fired together and two men fell. There was confusion in the ravine, some pushing on and some turning back. Sullivan waited a moment and then fired six shots so fast that it sounded like a burst of machine-gun fire. On the other side the Mongols opened up, and Hulagu’s men from the foot of the cliff kept up a rapid fire.

‘One,’ said Olaf, calmly reloading. Li Han aimed at the white horse and fired at last: he struck an escaping man fifty yards in the rear.

In the van of the Kazaks the yak’s tail banner tossed and waved. There was a piercing shout from below and the banner rushed forward, with fifty men behind it, charging for the dismounted men at the foot of the cliff. In a moment they had swept by the withering fire from the heights, and they were engaged in a battle at hand to hand, so close that the men above could not fire without hitting their own friends.

The Kokonor men were outnumbered more than two to one: the sheer cliff was behind them, and they could not fly.

‘Professor, stay here with Derrick and Chingiz. Pick off the Kazaks down the valley,’ said Sullivan, as he lowered himself over the side. Ross was already going down before him, and Olaf followed fast. On the far side the Kokonor Mongols were also climbing down. One fell, and rolled the whole length of the steep slope to a Kazak lance.

Ross was the first down, but Sullivan out-paced him to the fight. Two horsemen came at him, and running he missed his shot, but he leapt aside from the nearer lance and sprang for the horse’s head. He wrenched horse and rider to the ground, and the second man came down in the threshing legs. The Kazaks bounded free and came for him again, but before they could strike he hurled his rifle at them. He was within their guard, and in each hand he held a Kazak by the neck. With a crack like a rifle-shot he smashed their heads together: the helmets rang and fell, and the Tartars dropped senseless from his hands.

Sullivan gave a bellow like an angry bull and dashed into the fight. A horseman, wheeling, cut the shoulder off his coat: as the horse reared Sullivan gripped the rider by the leg and jerked him down. The Kazak fought like a wild-cat: Sullivan raised him, hurled him down on the rocks and then flung his body into the knot of swordsmen surrounding Hulagu. He followed right behind the hurled body, roaring and striking right and left.

The battle was more even now. Ross, using his rifle as a club, was over on the right, taking the Tartars from behind: Olaf was by his side, with a boulder in each great hand that converted his fists into two deadly maces. A rush of horsemen from the farther end was checked by the men above: the Professor had the hang of his weapon now, and now even Li Han could hardly miss. Only four men got through.

In the middle of a ring of Kazaks, Sullivan fought like a man possessed. He had no weapons, but he held a man by his feet, and whirling him round he drove the Kazaks before him. They scattered, and he threw the body with all his force, knocking three of them down. From one of the fallen men he snatched a sword, and for a moment he stood alone. It was a long blade, heavy and straight: he shifted it in his hand. It was a brave man who came against him, Attay Bogra, the son of the Altai Khan. The blades leapt in the sunlight, hissing against each other, hissing and clashing so that the noise was like the noise in a smithy when two men hammer on the iron. They went to and fro, and men fell back from either side of them. The red wound from a half-parried blow sprang open on Sullivan’s forearm, and the blood flowed fast. He gave back a step, but as he stepped the Tartar lunged, slipped in a pool of blood and almost fell. He straightened, saw Sullivan’s sword whip up in both hands to the height above him, and flung up his sword against the blow, but in vain: the sword flashed down, a blinding arc of light, and through helmet, skull and bone the sword bit to the ground. The Tartar fell, clean cut in two. There was a great cry, and a moment of sudden panic among the Kazaks. At this instant the Kokonor Mongols from the farther cliff reached the bottom – they had had a longer and a steeper climb, but now they flew into the fight.

Sullivan wiped the blood from his eyes and glanced around to find the thickest of the fray. There was none. The Kazaks were already horsed, and the survivors were racing down the gulley.