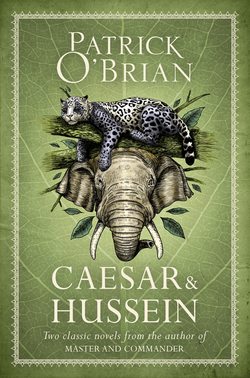

Читать книгу Caesar & Hussein: Two Classic Novels from the Author of MASTER AND COMMANDER - Patrick O’Brian - Страница 5

Foreword

ОглавлениеIt is a curious experience looking back from a distance of more than seventy years at the little creature who shared one’s name, bones, and indeed a good deal of one’s essential being, as far as it can be made out at all objectively. Curious and by no means entirely agreeable: I doubt if my present self would have liked the twelve-year-old boy who wrote this tale — he was certainly not very popular among his brothers and sisters. Nevertheless, that remote being and myself, his aged descendant, are linked by a common delight in reading: the boy read voraciously, often in bed, by the light of an electric torch. And when he was very young his stepmother, the kindest of women, took him to see her sister, who gave him the Reverend Mr Wood’s Natural History, a mid-nineteenth-century edition illustrated with a fair number of engravings. Since he was already something of a naturalist (an admired, much older brother had practically invented birds), the boy devoured the book, which was written by a sensible, well-informed, scholarly man. The boy was also something of an invalid, which interfered with his education and worried his father, a bacteriologist in the early days of vaccines and electrical treatment: the young fellow (pre-adolescent: a sort of elderly child) therefore spent long sessions in the incubator room, sitting at a glass-topped metal table and doing the simple tasks set by his tutor. But the tasks left a good deal of time unoccupied, and since it was obviously unthinkable to bring a book to read, the boy, by some mental process that I can no longer recall, decided to write one for himself, thus discovering an extraordinary joy which has never left him — that of both reading and writing at the same time.

It may seem absurd and pretentious, above all apropos of this piece of juvenilia, to say that writers, once they have experienced this intense delight, live fully only when they are writing fast, at the top of their being: the rest of the time only the lacklustre shell of the man is present, often ill-tempered (deprived of his drug), rarely good company.

I cannot remember the genesis of Hussein with great clarity, but I rather think that it derived from a tale I wrote for one of the Oxford annuals, to which I contributed fairly often: Mr Kaberry, an amiable man who ran the annual, said that it would be a pity to publish no more than the abbreviated form I showed him, and suggested that I should expand it to a book.

This I did: I was living in Dublin at the time, in a boarding-house in Leeson Street kept by two very kind sisters from Tipperary and inhabited mostly by young men studying at the national university with a few from Trinity. What fun we had in the evenings: the Miss Spains from Tipperary danced countless Irish dances with wonderful grace, big-boned Séan from Derry sawing away at his fiddle and the others joining in as well as they could. On Sundays we would go to a church where, without impropriety, the priest could say his Mass in eighteen minutes; then we would ride to Blackrock to swim; and all this time the book was flowing well, rarely less than a thousand words a day and sometimes much more. I finished it on a bench in Stephen’s Green with a mixture of triumph and regret.

Although I had known some Indians, Muslim and Hindu, at that time I had never been to India, so the book is largely derivative, based on reading and on the recollections, anecdotes and letters of friends of relations who were well acquainted with that vast country; and it has no pretension to being anything more than what it is called, an Entertainment. But it did have a distinction that pleased my vanity: it was the first work of contemporary fiction that the Oxford University Press had published in all the centuries of its existence.

It was fairly well received, and in the writing of the book I learnt the rudiments of my calling: but infinitely more than that, it opened a well of joy that has not yet run dry.

PATRICK O’BRIAN

Trinity College, Dublin 1999