Читать книгу When They Call You a Terrorist - Patrisse Khan-Cullors - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеintroduction

WE ARE STARDUST

I write to keep in contact with our ancestors and to spread truth to people.

SONIA SANCHEZ

Days after the elections of 2016, asha sent me a link to a talk by astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson. We have to have hope, she says to me across 3,000 miles, she in Brooklyn, me in Los Angeles. We listen together as Dr. deGrasse Tyson explains that the very atoms and molecules in our bodies are traceable to the crucibles in the centers of stars that once upon a time exploded into gas clouds. And those gas clouds formed other stars and those stars possessed the divine-right mix of properties needed to create not only planets, including our own, but also people, including us, me and her. He is saying that not only are we in the universe, but that the universe is in us. He is saying that we, human beings, are literally made out of stardust.

And I know when I hear Dr. deGrasse Tyson say this that he is telling the truth because I have seen it since I was a child, the magic, the stardust we are, in the lives of the people I come from.

I watched it in the labor of my mother, a Jehovah’s Witness and a woman who worked two and sometimes three jobs at a time, keeping other people’s children, working the reception desks at gyms, telemarketing, doing anything and everything for 16 hours a day the whole of my childhood in the Van Nuys barrio where we lived. My mother, cocoa brown and smooth, disowned by her family for the children she had as a very young and unmarried woman. My mother, never giving up despite never making a living wage.

I saw it in the thin, brown face of my father, a boy out of Cajun country, a wounded healer, whose addictions were borne of a world that did not love him and told him so not once but constantly. My father, who always came back, who never stopped trying to be a version of himself there were no mirrors for.

And I knew it because I am the thirteenth-generation progeny of a people who survived the hulls of slave ships, survived the chains, the whips, the months laying in their own shit and piss. The human beings legislated as not human beings who watched their names, their languages, their Goddesses and Gods, the arc of their dances and beats of their songs, the majesty of their dreams, their very families snatched up and stolen, disassembled and discarded, and despite this built language and honored God and created movement and upheld love. What could they be but star-dust, these people who refused to die, who refused to accept the idea that their lives did not matter, that their children’s lives did not matter?

Our foreparents imagined our families out of whole cloth. They imagined each individual one of us. They imagined me. They had to. It is the only way I am here, today, a mother and a wife, a community organizer and Queer, an artist and a dreamer learning to find hope while navigating the shadows of hell even as I know it might have been otherwise.

I was not expected or encouraged to survive. My brothers and little sister, my family—the one I was born into and the one I created—were not expected to survive. We lived a precarious life on the tightrope of poverty bordered at each end with the politics of personal responsibility that Black pastors and then the first Black president preached—they preached that more than they preached a commitment to collective responsibility.

They preached it more than they preached about what it meant to be the world’s wealthiest nation and yet the place with extraordinary unemployment, an extraordinary lack of livable wages and an extraordinary disruption of basic opportunity.

And they preached that more than they preached about America having 5 percent of the world’s population but 25 percent of its prison population, a population which for a long time included my disabled brother and gentle father who never raised a hand to another human being. And a prison population that, with extraordinary deliberation, today excludes the man who shot and killed a 17-year-old boy who was carrying Skittles and iced tea.

There was a petition that was drafted and circulated all the way to the White House. It said we were terrorists. We, who in response to the killing of that child, said Black Lives Matter. The document gained traction during the first week of July 2016 after a week of protests against the back-to-back police killings of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge and Philando Castile in Minneapolis. At the end of that week, on July 7, in Dallas, Texas, a sniper opened fire during a Black Lives Matter protest that was populated with mothers and fathers who brought their children along to proclaim: We have a right to live.

The sniper, identified as 25-year-old Micah Johnson, an Army reservist home from Afghanistan, holed up in a building on the campus of El Centro College after killing five police officers and wounding eleven others, including two protesters. And in the early morning hours of July 8, 2016, he became the first individual ever to be blown up by local law enforcement. They used a military-grade bomb against Micah Johnson and programmed a robot to deliver it to him. No jury, no trial. No patience like the patience shown the killers who gunned down nine worshippers in Charleston, or moviegoers in Aurora, Colorado.

Of course, we will never know what his motivations really were and we will never know if he was mentally unstable. We will only know for sure that the single organization to which he ever belonged was the U.S. Army. And we will remember that the white men who were mass killers, in Aurora and Charleston, were taken alive and one was fed fast food on the way to jail. We will remember that most of the cops who are killed in this nation are killed by white men who are taken alive.

And we will experience all the ways the ghost of Micah Johnson will be weaponized against Black Lives Matter, will be weaponized against me, a tactic from the way back that has continuously been used against people who challenge white supremacy. We will remember that Nelson Mandela remained on the FBI’s list of terrorists until 2008.

Even still, the accusation of being a terrorist is devastating, and I allow myself space to cry quietly as I lie in bed on a Sunday morning listening to a red-faced, hysterical Rudolph Giuliani spit lies about us three days after Dallas.

Like many of the people who embody our movement, I have lived my life between the twin terrors of poverty and the police. Coming of age in the drug war climate that was ratcheted up by Ronald Reagan and then Bill Clinton, the neighborhood where I lived and loved and the neighborhoods where many of the members of Black Lives Matter have lived and loved were designated war zones and the enemy was us.

The fact that more white people have always used and sold drugs than Black and Brown people and yet when we close our eyes and think of a drug seller or user the face most of us see is Black or Brown tells you what you need to know if you cannot readily imagine how someone can be doing no harm and yet be harassed by police. Literally breathing while Black became cause for arrest—or worse.

I carry the memory of living under that terror—the terror of knowing that I, or any member of my family, could be killed with impunity—in my blood, my bones, in every step I take.

And yet I was called a terrorist.

The members of our movement are called terrorists.

We—me, Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi—the three women who founded Black Lives Matter, are called terrorists.

We, the people.

We are not terrorists.

I am not a terrorist.

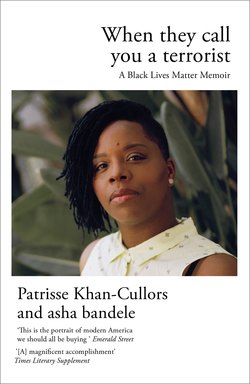

I am Patrisse Marie Khan-Cullors Brignac.

I am a survivor.

I am stardust.