Читать книгу Beyond Paris - Paul Alexander Casper - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3.

Going East to Meet the Czar

Оглавление10:15 PM, April 13, 1970

Our excitement and anticipation levels were off the scale as we dragged our bags through the train’s hallowed hallways. Funny, I thought, not the hallways or compartments that I had been imagining. “How ya doing, Doug? I’ve had enough; these bags sure don’t get any lighter the longer you carry them, do they? We’ve gone through about a thousand cars so far. I’m tired and, by the way, haven’t seen any of your movie stars or anyone who might look like a spy. I can’t go another step—how about this compartment?”

“Okay, why not,” Doug responded.

We collapsed into ornate-looking couch-sized seats facing each other. As we were about to experience repeatedly, even though our Orient Express was supposed to depart Gare de l’Est at some time in the early evening, we didn’t leave until closer to 11:30. For the last couple of hours, we had tried to check out more of the train. We just weren’t finding any interesting characters—as I saw it, we were the most interesting people on the train.

Unfortunately, at 3:00 a.m., as I was finally starting to fall asleep, a non-English speaking conductor didn’t find us interesting at all.

What was supposed to be a simple ticket and passport check as we crossed into Germany almost had us thrown off the train. Our conductor was furious and wildly throwing his arms around, making it known this was not a compartment for us as he threw our baggage into the hallway. We finally understood; we were in a first-class compartment, and we most certainly were not first-class travelers. We followed him through numerous train cars until he finally stopped at one containing a young German who looked somewhat like a fellow traveler.

The remainder of the night went fast, with hardly any sleep. Early the next morning we entered the huge main train and switching stations in Munich, Germany. We had to exit the train with all our baggage for an eight-hour layover. After changing some money, we bought some food and walked around Munich for a while after we put our baggage in a rented locker.

Back at the station in one of its many cafes, having a regular beer in a glass that looked a foot tall, we met a student from Denmark. He was trying to decide whether to go back to the university or keep traveling. He’d been gone six or seven months. We were on our way to Istanbul; he had just been in Istanbul. His English was fair, sometimes hard to understand. But what caught our attention was his warning about traveling from Turkey east to India. India was great, he said, but watch out for Iraq and Iran; gun battles seem to spring up in every town. He also alerted us that because the conditions were so miserable in those desert countries, many of the gangsters were moving west to exactly where the Orient Express was headed next—Yugoslavia and Bulgaria.

We bought him another beer in hopes of finding out more about—I couldn’t believe I was saying this: “Gangsters!”

Before we could continue to give him the third degree, we heard an announcement over the public address system, luckily in English, that our train was going to be leaving shortly from track 27.

And again, we had no sooner picked what seemed to be a very nice and cozy compartment when a conductor was at our door asking to see our tickets, motioning us to follow him as he shook his head from side to side mumbling to himself in German. Many cars later, there was no doubt in my mind that not only were we leaving first-class accommodations, we were apparently not stopping in second class either. In each car, the compartments looked worse. Finally, he stopped and signaled us into a beat-up compartment already occupied by what appeared to be an elderly Yugoslavian couple with a ton of luggage.

Okay, I thought, we had gotten used to having the space to ourselves, but why not, this was more interesting. We could manage, we could do this, it was how the compartment was designed. Two people on one side, two on the other—but why did they have to have so much baggage?

As we got closer to the Yugoslavian border, the train started making many more stops. Doug and I scouted some other cars. Many of the compartments were filling up; some, it appeared, were too full. I started to wonder, could—and before I finished that thought, we turned the corner to our compartment. A new German guy was sitting on our side.

It was now kind of uncomfortable, but tomorrow morning we would be in Istanbul. We could manage this, even though now it had been thirty-something hours with very little sleep and sitting up the whole time. But in talking to the German guy, we discovered to our disbelief that no, not tomorrow morning, but not until sometime the day or night after tomorrow would we arrive in Istanbul. The feeling was indescribable. I laughed to keep from crying.

Another hour passed. The farm couple had opened some bags of food that seemed by their odor to be way past their expiration dates, assuming they even had such things in the small villages and towns where we stopped. By now, there was no room for many of the villagers, and they just dropped their bags in the corridor and sat next to or on them. Walking between compartments had become nearly impossible.

A hulking Turk suddenly barged into our compartment, very drunk and wanting to befriend anyone who would look his way. The German couldn’t take it anymore and fled.

Not long after the Turk also left, and we thought we had caught a break. But no. He came back with three of his friends, a teenage girl and two guys—and all had been drinking heavily.

Now we had eight instead of the recommended four people in our compartment. The girl sat across from us, and two of the more sinister-looking Turks bookended Doug and me, with the original Turk, Mehmet, sitting on a suitcase in front of the window.

“Swede…no, English,” remarked Mehmet as he cut pieces from a rotten-looking piece of fruit he had taken out of a bag. Was he cutting it with a knife? Nah, more a machete.

Confused, Doug and I looked at each other, and I answered, “No, American.”

“Oh, Americano,” Mehmet said with a sly smile. The two bookend Turks nudged us and nodded their heads and grinned.

“Tourists, how you say, para? Money? Tourists,” he said, rubbing two fingers together on the other hand not holding the very big knife. “Where you from?”

“Chicago and New York,” Doug whispered, hoping not to encourage this line of questioning.

Mehmet smiled. “Very much money. Tourists, I think.”

“No, no, we are just students—just poor students.”

The conversation continued, but I was starting to notice the young girl sitting directly across from me. Her body was swaying, and her hand frequently came up to rub her eyes or hold back belches, as if a hand could do that. She—we’ll call her Jane for lack of a better name—was starting to be in trouble. Her eyes were roaming, moving up in their sockets. She had been drinking, of course, but the odor wafting from our passengers and their food was enough to make anyone nauseous.

I thought, how can this be? This was not the prisoner train from Dr. Zhivago; this was the Orient Express! Where was Sean Connery; where was 007; where were the beautiful heroines or evil-but-gorgeous female foreign spies? This was the Orient Express; I should be having dinner in the club car, sipping expensive wine and listening to furtive whispered conversations at the other tables. And my dinner partner should be Greta or Ursula, not Mehmet.

And as I was starting to fantasize about Ursula—think Ursula Andress, the 1960s movie star—Mehmet changed places and sat beside me. He put his arm around my shoulder as he said, “You Americanos should come with us. We Gypsies. We take you for…I mean, we, bok”—that was clearly an expletive—“how you say… we show you a good time. No problem, we have money; you have money. How much money you have?”

At that moment, much to my relief, Jane jumped up, screamed three words in Turkish, and dove for the door, barely managing to slide it open before she heaved her guts into the hallway. The contents of her stomach landed between two huge Yugoslavian ladies, who seemed to not only not notice but not care. They continued arguing with anyone who would speak to them.

Somehow, one of the conductors cleaned up the mess. Before he could disappear, Doug and I begged him for relief, any relief. He motioned again with his fingers, as many Europeans seemed to do in our company, signaling, It’ll cost you, but get your bags and follow me. He took us to a sleeper with two English girls. Morning was almost upon us, and we were just falling asleep when a new conductor burst in asking for our passports and visas. The train was entering Communist Yugoslavia.

He stood in front of us, yelling and gesturing. “I know, I know,” I said. “No visas.” Having gained wisdom from recent experience, I thought it appropriate to hold out my hand and rub my thumb and forefinger together as I repeated the word “visa” in pigeon Yugoslavian. We walked into the hallway, the conductor negotiated payment with the border guard, and we were given two slips of paper with stamps on them—they looked official.

The conductor indicated we were lucky. We could have been taken off the train and even jailed: we were lucky to get that guard. As we were walking away, we heard the conductor talking to himself, “Bulgaria won’t be as easy, and I will not be here to help you; you’ll have another conductor.”

Back in our compartment, I think we would have started to do some major worrying if we weren’t so tired—but within ten seconds, we were out cold.

We woke up mid-morning to the girls holding hot pastries under our noses. They had jumped off the train and gotten food items from vendors like those we had seen on the platforms as we passed through so many small, dismal-looking Eastern European towns.

The girls, Chelsea and Alice, were on holiday to meet one of their grandmothers in Istanbul, a woman whose late husband had been a British attaché to Turkey about thirty years earlier. They were going to travel south along the seacoast for a couple of weeks.

The train wound through the dreary Yugoslavian countryside slowly, but we were grateful to have a day so calm after the chaos of the night before.

Doug and I jumped out a couple of times when we stopped—what seemed like fifty times, in every town we passed through—to buy food from a vendor. Most of the vendors were selling the same indeterminate meat between slices of the same stale-looking gray bread.

The drinks were all takeoffs on American soft drinks like Coke and Pepsi, but the tastes were very different and highly suspect. The endless hours looking out our windows as we chugged up hills and rolled down the other side were so desolate, they prompted me to write a poem about the very mysterious Orient Express.

As I continued to draw our travel line on my map, starting in Luxembourg, then to Paris and now leaving the large Belgrade station, it became clear to me that I had to find another map. This one, although perfect and large, only went as far east as Istanbul. I needed one showing Iran, Iraq, Pakistan and Afghanistan—the entire route to India. As I read my map and scratched my face something else became clear: I was growing a beard. This was a first for me.

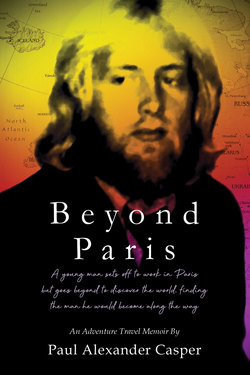

Yes, it wasn’t much of one, but after more than a month not shaving, I had more than stubble. I glanced at my reflection in the window and decided I liked it. It looked rugged and adventurous, appropriate for this time in my life. The idea of a different look appealed to me, and I had started to comb my hair, which I had grown considerably since I left the States, straight back. My new life would be devoid of modern bath facilities and mirrors, I guessed, and low-maintenance would be best. I reminded myself of a blond, younger Barry Gibb, think early Bee Gees. My hair was more than creeping over my collar, but I managed to control it by frequently dampening it with water, often raindrops. No matter where we went in what country we passed through, it was raining. When we did a food run, it inevitably poured more heavily. It had rained all or part of every day we’d been in Europe—hopefully, the gateway to the East, Istanbul, would have some sunshine for us.

The rain finally did end; it began to snow. For some of the afternoon and into the evening, that consistently gray landscape was slowly but surely whitening with falling snow. It looked so cold outside. I sure hoped Istanbul was far enough south that we wouldn’t have to worry about snow. I consoled myself by thinking about all the sheepskin coats we would buy in India. We would have plenty of furs to protect us from any degree of chill—and plenty of money to put in our pockets, which would also shield us from the cold.

As we turned in, we all talked about Istanbul. Incredible, we thought, the gateway to the East, the jumping-off point of the Crusades. Historic Paris was different from anything I had ever experienced—it had been the thrill of my lifetime. But now we would be going even further back in time, to the land of warriors of old and the sultans of the desert.

It seemed we had no sooner fallen asleep when we heard that familiar, “Attention! Attention! Messieurs and Mademoiselles, passport inspection.” It was three o’clock in the morning. I could hear the train puffing outside the window; the metal beast was impatient. It didn’t want to stop; it wanted to run. I could feel that restlessness vibrating in the compartment. Our new conductor agreed; he wanted to make this border stop a quick one. I was impressed with Doug’s ability to stay asleep while he found his passport and passed it to the conductor without opening his eyes. As I lay there waiting for the conductor to return with our passports, I did wonder if we had taken the prospect of last night’s calamity happening again seriously enough. This was a Russian territorial partner; we were in the grasp of the Communist empire.

My worry was not unfounded; whatever last night was, this was starting to feel much worse. Moments later numerous guards, conductors and even passengers were crowding into our compartment and yelling at us to get up and follow them. They took Doug and me out onto the platform. There was no negotiating. This was rough; no one was speaking English, and there were many more guards coming from around the corner, all with machine guns. I watched our conductor as all this was happening. He was quiet and showed no emotion. Some passengers tried to come out onto the platform, but a few guards pushed them back, with everyone yelling in multiple languages. The guard who looked to be in charge was talking on a hand-held radio device, I assume to his superiors. He kept saying what sounded like “American CIA.” That may have been my imagination. As he talked he pointed towards the station house. I looked inside and saw bars on the window—and in a dark corner of the room what looked like bars from the floor up to the ceiling. Was their next move to put us behind bars? The border guards had an entrance far down the line from the station door entrance. I muttered to myself, This is it, and it is bad. We are in Bulgaria; these guys are probably meaner than the Russian guards. This is a dark country; not good. I bet Bulgarians don’t even like other Bulgarians, let alone foreigners. The one guard kept on saying, “Net visa, net visa!” I wondered what the word for spy was. Had he said it many times already?

I wondered what nationality our conductor was. I hadn’t heard him speak at all since Doug and I had begun pleading for leniency. Doug never stopped trying to get us out of this; he even got down on his knees. It was impressive; I believe he tried words in languages he didn’t speak, to no avail. Just then, the border guard leaned his semi-automatic against a pillar. I was sure he was in the process of getting a pair of handcuffs out, to cuff Doug. Okay, it had just gone from bad to very bad to no way; we were going to be arrested in Bulgaria. My mind started to fly—jail, then what—do they even have a judicial system, or do they just throw people immediately in dark, dingy Communist prisons? My imagination was out of control. Were there places worse than bad prisons where they lock up the spies and throw away the keys?

A second border guard ran up, yelling and motioning for the guards harassing us to come quickly. I couldn’t understand what the problem was, but it appeared to be more serious than the need to detain the two American spies. At that moment, our previously silent conductor jumped in and handed one of the border guards our passports, apparently saying he’d take responsibility for the two spies, making sure they would never touch Bulgarian soil again. He appeared to ask his friend Borislav if he could okay us quickly, as the train had been held up way too long? The guard looked at the conductor, looked at us, looked at his partner, looked at the new, approaching guard and threw up his hands. Swearing up a storm in Bulgarian, he stamped our passports and ran off to solve whatever the new crisis was.

As we boarded the train our conductor admonished us in perfect English: “You fools are very lucky; they were going to transport you up to Sofia (the capital of Bulgaria.) They have a terrible prison there. Who knows when they would have remembered you were even in there!”

Yes, we were lucky, but the unpleasantness wasn’t over yet. Over the sound of my heart racing, I heard furious comments from other passengers and saw the dirty looks aimed at Doug and me. The train was very off schedule now, and the two American idiots were to blame.

Sleep was out of the question. Eventually, I couldn’t take it anymore and quietly moved out into the hallway, where I sat down on the floor next to a dim hallway light. It was the middle of the night, but the huge train was just now quieting down. It had been an hour or so since the Paul & Doug Spy Variety Show.

I fell asleep in the passageway, waking when I was gently kicked by our friend and savior, the conductor. We had another border check as we crossed into Turkey.

At our stop in Edirne, the border town, I woke up Doug. We ran out to find something to eat on yet another train platform. Folded dough sandwiches stuffed with something unidentifiable was the best we could do, but we were hungry, and they disappeared fast.

Standing in the hallway next to the open windows, Doug and I talked about getting off this hell on wheels and onto, we hoped, a much better sister train that could take us east to Afghanistan and India. We would stay overnight in a hotel and leave again the next morning, arriving in India, hopefully, in a few more days.

About an hour away from Istanbul, I stood in the hallway smoking my cigarette, watching camels, unbridled and wandering free, dotting the landscape. The wonder of that made all the trauma with the border guards almost worth it. Yeah, I was entering another world for sure.

My reverie was interrupted by Doug, who came around the corner and asked if he could have a couple of cigarettes for himself and a guy he had just met. Introductions were made. “As-salamu alaykum,” nodded the nicely dressed gentleman as I lit their cigarettes. (I only had two Marlboros left. Would I have to start smoking foreign cigarettes?) Our new smoking buddy, Dr. Sevim, was a doctor, of what I did not know. He was about forty years old and better dressed than anyone else I had seen on the train. Born and raised in Istanbul, he had traveled extensively east and west during and after schooling. He was much more interested in us than he was in talking about himself and was especially interested in Doug’s updates on New York City, where he had studied ten years ago.

After a few minutes, the conversation still on NYC, I started to drift, wondering what the next couple of days would bring. I almost wished we were planning to spend more time in Istanbul, one of the world’s oldest and most mysterious cities.

I raised my hand. “Doctor, pardon me, if I may, you greeted us just before with a phrase I’ve heard numerous times on this train. I believe it was something like ‘salum alaken.’ What does it mean, and should we be using it as we make our way into Muslim lands?”

He responded, “The Muslim greeting ‘As-salamu alaykum’ means ‘Peace be upon you.’ And then the usual response would be ‘Wa-Alaikum-Salaam,’ which means ‘And unto you peace also.’” I seemed to have hit an important chord with this question, and he continued. “Islam is a wonderful way of life; the way of it is so wonderful. The norm of specifying how it should be put forth: ‘As-salamu alaykum’ meaning ‘peace be upon you’ or more perfectly: ‘Assalamu alaikum wa rahmatullahi wa barakatuh,’ meaning peace, mercy and blessings of Allah be upon you.’ In this regard, Allah says in the Qur’an: ‘And when you are greeted, greet (in return) with one which is better than it or (at least) return it (in like manner).’ For Allah is ever taking account of all things. The greeting Allah is referring to here is generally understood to be ‘As-salamu alaykum.’”

I asked about the hand movements he had previously used addressing us and he explained “salaam,” which he described as “a greeting from Allah, blessed and good.” He clarified how it is done: “The full salaam is a traditional greeting in Arabic-speaking countries and Islamic countries. It is made by sweeping the right arm upwards from the heart to above the head. It begins by placing the hand in the center of the chest over the heart, palm to chest, then moving upwards to touch the forehead, then rotating the palm out and up slightly above head height in a sweeping motion. In the abbreviated salaam, the head is dropped forward or bowed, and the forehead, or mouth, or both, is touched with the fingertips, which are then swept away. Now having just said that, the gesture is losing popularity. I prefer it and always have. I will always use it myself as a sign of respect.”

The doctor asked where we were headed after Istanbul. Doug explained our plan to continue to India and get rich by becoming clothing industry entrepreneurs. He thought the idea had merit; he knew of the burgeoning popularity of sheepskin coats in the West, but his voice trailed off as he turned and looked out the window. He said, “I sure don’t envy the journey you have left.” That caught my attention.

“What do you mean—we heard it was only another couple of days.”

And so, before he left to pack his belongings a couple of cars ahead, he proceeded to demolish our best-laid plans.

Yes, he said, to India was about two days but only by airplane. For the last six months there had been not only no direct train but no continuous train travel at all between Istanbul and Baghdad, which was close to the border with Iran. He had heard from some relatives that just as you entered Iraq, all train tracks were out. Now, that might sound ridiculous, he cautioned us, but not if you knew the government in Iraq. You had to travel by bus and, he warned, this was not a bus like any we’d ever ridden or that he’d ever want to take. Even worse, as you reached the eastern edge of Iraq and started to make your way into Iran, you had to watch out for gangsters. Unfortunately, he added, human life is not what it is in America, so beware. Warming to his theme, he implored me to dye my hair. A blond would stand out...my golden locks would be like having a spotlight following me wherever I went. Blond would mean I was either English or Swedish or—even more mouth-wateringly inviting to the bandits—a rich Americano. These gangsters thought nothing of shooting people just to shoot them. As a final warning, he added, if I were you, I’d figure between five and seven days to get there, depending on the weather, because we’re getting close to the sand-storm season in Iraq.

Seven more days of traveling in much worse conditions than we had experienced for the last three and a half days.

There was no way, both of us exclaimed after Dr. Sevim left.

We couldn’t even begin to imagine seven more days of sitting up day and night in trains and buses and God knows what else before we got there, if we ever got there. And what did he mean, gangsters? It was 1970, but he had warned us that many parts of these two huge countries, Iraq and Iran, were lawless. He explained that sometimes they come on horses, sometimes in trucks and sometimes they just appear out of nowhere. There definitely was no sheriff in town or evidently anywhere in either country.

These were our choices? Give up our perfect plan of getting to India, going into the clothing business and becoming rich, or spend the next week traveling in who-knows-what type of conditions? And experience had taught us that there would be much more time required to get all the proper visas and papers and special inoculations we would need.

Well, the worst that could happen were about a million and one things and all of them very bad. Yes, Dr. Sevim had said I would always be greeted with a smile if when meeting anyone in the East I first greeted them with “As-salamu alaykum,” Peace be upon you. I planned to do this, but I was afraid that if someone addressed me first with ‘As-salamu alaykum’ I would completely forget what to say in response.

Doug touched my arm and looked at the skeptically and I tried to read his mind: If we are really stopped somehow by middle-eastern gangsters do you think what we say to them will mean anything? And before we even opened our mouths, they would probably have already taken all our clothes and gone through our pockets looking for anything of value. I remember you talking earlier on our trip about how much you liked those old black & while road movies with Bob Hope & Bing Crosby. Well I’ll tell you, we are not on the Road to Rio—we could be on our way to the Road to Big Long Knives. Could there be anything worse?

And then, of course, there were the gangsters. What would be the worst that could happen?

Doug cut to the chase: “The worst is we get drilled with holes or worse, that’s the worst and forget it—forget all of it.” I agreed. That was that; we would not be going to India. We would not be going into the clothing business. We would not be getting rich, at least not that way. But as the train slowed down, coming into Istanbul station, I wondered, if not that, if not there, then what? We were almost halfway around the world—what would be next?