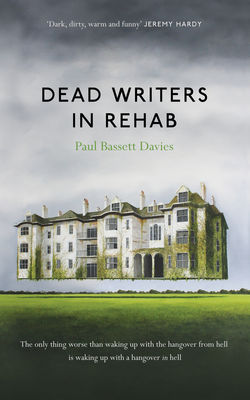

Читать книгу Dead Writers in Rehab - Paul Bassett Davies - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Patient FJ

Recovery Diary 2

ОглавлениеThe bastards. My friends, those bastards. And at least one bitch of a wife could be involved, almost certainly my first, as I’m pretty sure the second one wouldn’t go along with something like this. Unless someone managed to convince her she’d be doing the right thing, and genuinely helping me in some unfathomable way. That’s always been the trouble with Paula: she’s far too trusting. But there again, she’s not naïve, and people who assume her sweet nature is a sign of gullibility are making a big mistake, especially if they try to use her to hurt me. But they might have convinced her to play along, the people responsible for putting me in here, whoever they are. My friends, colleagues, rivals, enemies – all of the above, or none – this is their doing. The bastards.

Okay, I accept that both those other times, when it was all over, I could see they’d been right. I hated it at the time of course, especially the first one, when the whole concept of an intervention made me physically sick as they cornered me in the kitchen, in my pyjamas, and explained it to me. I was probably going to be sick anyway, given my condition, but ever since then I can’t hear that word, intervention, without feeling the bile rising in my throat. I stood there with my back to the sink, gazing at them like some poor, dumb, bewildered badger about to be torn to pieces by a pack of slavering hounds who’ve somehow learned to speak a special smug, sanctimonious language all about denial and responsibility and co-dependency.

But they were right. It probably really did save my life. Especially the first time, when I woke up in what turned out to be The Priory. The second time was a bit different, as I knew what was happening and where I was being taken (which turned out to be a less expensive facility, because I wasn’t selling so well by then, and the TV series hadn’t been recommissioned, and the screenplay had been given to someone else, to be ‘improved’ in the way that a heretic is improved by being burned at the stake).

But that was rehab. This time the bastards have put me in a fucking nuthouse.

Why? I’m not nuts. I’m not even drunk any more. Clean and sober for five years. During which my behaviour has been exemplary, by my standards. It’s been a long time since I had a fight or broke something valuable, like a Ming vase or a marriage, or caused a major embarrassment in public or told someone what I really think of them. I’m still a cunt but that’s just me. In fact there’s a good case for not giving up any of your bad habits, because when you do you’ll discover you’re just the same only now you’ve got nothing to blame it on. However, I gave it all up, and whatever makes me intolerable now isn’t drink or drugs. And not mental disorder, either. I’m probably the sanest person I know. So what’s all this about? Who has put me in here and why?

After my encounter with Hatchjaw I went back to sleep.

When I surfaced again I had no idea how long I’d slept. My mind was a blank.

I decided not to panic. I’d tried that before and it had never worked.

Slowly I began to remember a couple of things. Unfortunately it didn’t help much, because the couple of things I remembered were that I knew very little about where I was except that I didn’t like it, and I knew nothing at all about what the hell was going on.

I became aware that it was daylight and I was starving. I hadn’t been fed, and I expect they thought it was the easiest way to lure me out of my room.

No one was loitering outside my door so I set off down the passage in the same direction as before. An easy choice, as my room is the last one in the corridor so they didn’t exactly need to lay a trail of cheese. I walked past doors on either side of me that were identical to my door, all painted blue, and all closed. I reached the point where I’d turned back last time. I paused to listen for telltale sounds of confessional drivel, which is what had stopped me in my tracks on my first expedition. I didn’t hear anything this time so I carried on.

The corridor led to a doorway. The door was open. I walked through into a large room, tastefully decorated, mainly in blue. Some big French windows were letting in a generous helping of daylight and fresh air. All very pleasant. But you could strap me into an orange jumpsuit and deprive me of all sensory stimuli, like some trembling peasant suspected by the CIA of harbouring unwholesome thoughts about democracy, and lead me into a room like this and whip the bag off my head, and I’d know exactly where I was. It takes more than a few coats of Dulux Blue Lagoon and some rubber tree plants to disguise an institution. There’s something in the DNA of a building like this, whether it’s a school, a prison or an old people’s home. Bad vibes.

I looked around. I couldn’t see any food but I could smell something cooking somewhere. There were three doorways out of the room, including the way I’d come in, and the French windows. A faint scent of something I recognised but couldn’t name drifted in from the garden and mingled with the aroma of distant cooking. The food smelled good and I wondered which was the quickest route to its source.

I became aware of someone breathing heavily behind me. I turned to see a burly, grizzled man slumped in an armchair near the door I’d just come through. He was glaring at a woman who was sitting as far away from him as she could get while still remaining inside the room. She was about 40, with big eyes, and she looked tired. She was studiously ignoring him. The grizzled man, who had a scrubby beard and looked as though he might have mislaid a trawler somewhere nearby, turned his gaze slowly away from the woman and looked up at me. I thought for a moment there was something familiar about him, but when he spoke I could hear he was American, and I don’t know any Americans who look like him – although I know a Scottish barman with similar facial hair and the same mottled, rosy complexion of someone who likes to get drunk quickly and uses spirits to do it. The American squinted up at me and shaded his eyes with his hand as if I were an enemy aircraft coming out of the sun. He growled at me:

‘How is it going with you?’

‘I’m rather hungry.’

‘That’s a good sign.’

The woman on the other side of the room gave a clearly audible snort. The American glared at her again. He seemed to lose interest in me. I heard a cough, and I noticed a person standing beside the French windows, apparently admiring the view. He turned towards me, took a few steps forward and performed a curt little bow.

‘Sir, permit me to direct you to the commissary,’ he said.

I stared at him. He was a short, balding man with peculiar little glasses and an immense, bushy beard. He was wearing a kind of frock coat made of corduroy, with a waistcoat to match, and a pair of chequered trousers.

He walked up to me and held out his hand.

‘May I introduce myself? I’m Wilkie Collins.’

I shook his hand. ‘Foster James. Pleased to meet you.’

‘The pleasure is mine, sir. You are newly arrived among us, I believe?’

‘Oh, yes,’ I said, grinning inanely, ‘fresh meat.’

He frowned and seemed about to ask me something but then his face cleared. ‘Fresh meat in search of fresh meat!’ he said, and laughed. He had rather a nice laugh, for a raving lunatic.

I laughed back at him politely, terrified that he might turn violent. He suddenly thrust out his arm and I sprang away from him, nearly falling over a low stool. He shot me an odd look. ‘Allow me to escort you,’ he said. He bent his elbow and waggled it at me. I understood what was expected of me so I took his arm like a shy debutante and allowed him to guide me to the door opposite the one I came in through. As we left the room I heard someone mutter something in which I caught only the word ‘asshole’.

As the nut job who thought he was Wilkie Collins led me along another corridor and towards the smell of food, he kept up a constant stream of pseudo-Victorian chatter about ‘assuaging the pangs of hunger’ with ‘revivifying comestibles’ and ‘fortifying refreshments’. I must say he did it all very well, and not just the language; his whole deportment, which was formal but chummy, seemed completely authentic, and much more convincing than most of the actors you see in films or TV adaptations of Victorian classics. He even smelled slightly musty.

After the bit about ‘fortifying refreshments’ he stopped abruptly. I stopped abruptly too, as my arm was still linked to his. He turned to me. ‘I must tell you,’ he said earnestly, ‘that you shouldn’t expect to find anything in the way of beverages that tend to intoxicate if taken unwisely, or, indeed, any unwholesome stimulant.’

I told him I knew far too much about this kind of place to expect to find any booze here. I was an old hand at this game, I said. For some reason he seemed very impressed by this remark. He narrowed his eyes and tilted his head back, as if taking the measure of me. After a moment he nodded sagely, patted my hand, and we set off again.

We reached what was clearly a dining room of some kind. There was a serving counter with steel shutters behind it, which were closed. The smell of cooking came from behind the shutters. I sighed.

‘Another hour or so until we lunch, sir,’ the little madman said, ‘but fear not; help is at hand for the hungry vagabond.’ He pointed to a large vending machine in the corner. We wove our way towards it between the tables and chairs that filled the room. The tables were round and each one seated four. There were about a dozen of them.

The machine contained soft drinks, chocolate bars and pre-packed rolls and sandwiches. ‘Fresh every day, I can vouch for it, sir,’ my new friend said. ‘Quite remarkable.’ He beamed at me behind his little steel-rimmed oval spectacles. His eyes were grey with tiny flecks of amber in them. I rummaged in my trouser pockets and came up with some change, but he put out his hand to stop me. ‘I see you are unaware of the system in place here, sir. Permit me.’ He reached into his coat pocket and produced a small, round token of some kind. It was vivid purple. He came up with another, smaller one that was green. He handed both the tokens to me. ‘That should suffice for a sandwich and a cordial.’

‘Thank you very much. Very kind.’

‘I trust you will repay me when you’ve become acquainted with the system.’

‘Absolutely,’ I said.

He put his hand on my arm and gave me a worried look. ‘I’m sorry to press the point, but I would be obliged if you do so at your earliest convenience.’

I looked at him. He was serious. This was definitely a loan. I nodded and treated him to a reassuring smile, then I got a cheese and tomato roll and a can of Diet Coke out of the machine. I unwrapped the roll and took a bite. Not bad. My companion watched with satisfaction. He bounced up and down on his toes a couple of times. His boots creaked. ‘Would you care to take a stroll in the grounds?’ he said. ‘I’ll gladly show you around.’

He watched me expectantly as I chewed another large mouthful. I swallowed it with a big, painful gulp. ‘No, thanks,’ I said.

He looked crestfallen. After glancing around quickly, he lowered his voice. ‘As a matter of fact I believe a confidential discussion between us would be of mutual benefit. We can talk as I show you around; that will also serve to allay suspicion.’

I took a swig of Coke. He frowned at me, and I was suddenly aware I was being rude, even if he was a lunatic. The little man’s formal courtesy, assumed or not, made me feel like a lout. I inclined my head briefly and placed my hand on his arm. ‘That’s very kind of you,’ I said, ‘but I’m rather tired now and I’d prefer to go back to my room. But I’ll take you up on the offer another time. Thank you.’

‘Very well. Can you find your own way back?’

I nodded, with my mouth full again.

So they’ve put me in the loony bin. I knew it wasn’t a normal rehab. Some of these joints have pretty strange ideas, but the whole point is to get some kind of grasp on reality. A man who’s firmly convinced he’s a dead Victorian writer, and has got the whiskers to prove it, is delusional and belongs in a mental institution. Which is obviously what this place is. Which means I must have done something that made whoever put me here believe I was insane. Which is very worrying because I still can’t remember a fucking thing.

It’s interesting, though, that Wilkie Collins was a notorious opiate hound. Addicted to laudanum in a big way, like a lot of the Victorians, including Victoria herself, according to some people. It’s certainly true that for most of the nineteenth century half the House of Commons and most of the Lords, including a lot of the bishops, were laudanum addicts, along with thousands of doctors, lawyers, teachers, governesses, and a vast, twittering army of spinsters who’d faint at the merest hint of depravity but found great relief from all manner of maidenly ailments in the little brown bottle of comforting medicine. To say nothing of the poor, if they could get it. So, if there had been such a thing as rehab in Wilkie’s day he would have been a good candidate for it. I wonder if the nutter who’s impersonating him here has gone to the extent of developing a real-life opiate habit. Not that I plan to ask him. What I plan to do is to get out of this place.

But what if I can’t? What if whatever I did was serious enough for me to be sectioned, and detained under the Mental Health Act?

Unless it’s more sinister than that. What if someone wants to get me out of the way, or punish me? An old enemy taking revenge. Christ, there are enough candidates. It could be a conspiracy, and they might have paid this place to certify me and when I try to leave I’ll find I’m a prisoner. Fuck, what am I saying? That’s basically the plot of a Wilkie Collins book. Get a grip. As soon as I feel a bit better I’m going to walk out of here.