Читать книгу Prison Break - True Stories of the World's Greatest Escapes - Paul Buck - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

OVER THE WALLS AND FAR AWAY

ОглавлениеAs the prisons of Britain grow desperately overcrowded, now is the time to consider escape. In fact, it would be morally irresponsible not to consider it, for when the authorities state that they must break the rules, the safety limits, to house all their miscreants, it becomes necessary to talk about escape as a way to safeguard the mental and physical wellbeing of those incarcerated in our prisons.

Unless, that is, you wish merely to damn them and leave them to their lot. If so, this is not the book for you.

Perhaps, too, we should reconsider the point of additional sentences for those recaptured after their escapes, unless they have committed other offences in the process. In some countries, it is legally acceptable to seek to escape because it is regarded as only human to do so.

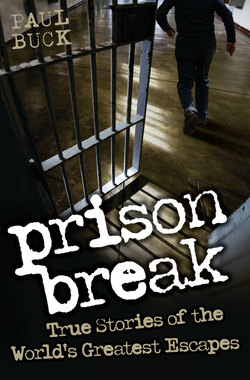

The focus of this book is notorious escapes, or ‘great escapes’, but only those of civilian prisoners. The idea is not to document escapes from the PoW camps of World War Two, for example, no matter how spectacular and heart-stopping many of them happen to be. Undoubtedly, we think of the Great Escape itself, Colditz and the Wooden Horse as part of our history, so much so that the accounts of civilian escapees since 1946 regularly refer to those historic wartime episodes, either because they were inspired to take on board particular details for their own escapes, or because the spirit and courage of the wartime escapees have fired successive prisoners with a sense of their own personal challenge. Steve McQueen in The Great Escape echoes through so many of their stories that his image, leaping the first fence on a motorbike, would not have been out of place on this book’s cover – even if no one here has taken that course of action as a mode of escape.

That said, I have included the IRA (Irish Republican Army) because, though a paramilitary organisation, their crimes were resolutely regarded as criminal rather than political, and thus, on the British government’s own terms, they have every right to be included here. (Another approach might have included those who escaped over the Berlin Wall during the Cold War, as one could view the Eastern Bloc on the whole as a prison.)

Our focus on civilian prisoners indicates that the escapees are those incarcerated for crimes, mainly robbery or murder. However, in general, I have rarely dwelt on the details of how those included found themselves in custody, unless it becomes necessary to the narrative. Likewise, the structure of London gangland, for example, is barely taken into account, as these matters are not particularly relevant to this work.

My intention has been to explore how the prisoner escaped, not to pursue the reason why. That would be another book in itself, and would include such reasons as: refusal of permission to attend a family funeral; to spend a few days with the family, wife or girlfriend, particularly if there was turbulence in the relationship; to prove one’s innocence; or to carry out a job that’s been lined up which will set the prisoner up for life (or so he hopes) – as well as the fundamental reason that people do not want to be imprisoned. Such a book would also have to explore strategies and stratagems to prevent escape.

This is a book about the escapee who thinks of little other than escape from the moment he is confined, as well as those who take the opportunity when it arises … be it a rope dangling over the prison wall or a door left unlocked, or open.

Why some people should escape while others do not is far from discernible. Some prisoners have observed that if someone is imprisoned for short spells they tend not to try to escape, whereas those same people may react more dramatically against a long sentence. Perhaps there is no real answer, but we can glean an insight or two as we examine individual cases.

Alfred Hinds, a master of escaping, summed up his observations thus: “The vast majority of prisoners are resigned if not content to do their bird. Some will escape if the chance is handed to them on a plate. But all they want is a brief taste of freedom; for instance, the chance to spend a few days with their wife or girl-friend. It usually is a brief taste, because they have no organisation and it’s almost a relief to them when they’re recaptured. Then there’s a small hard core of determined men who will plan an escape and go through with it. These are usually prisoners with long sentences of P.D. [preventive detention] but nothing to come out to. If a professional criminal has managed to salt away some loot, he’ll accept a sentence of five years or even more. If he hasn’t, he’ll want to get out and pull off a big job, after which he won’t mind too much being re-arrested. In his curious logic, he accepts his sentence as a just reward. The snag is that, if caught, he gets another and longer term of imprisonment.”

This book has primarily been an adventure in unravelling the different approaches to escape. I am not sure that, like many an escapee, I knew where it would lead, if I would draw any conclusions, or if I would end up back at the beginning. But I suspected that, in the process, I would discover something about my attitude to the issues raised. Perhaps one cannot ask for more. Perhaps this is what I want for the reader.

Here you will find escapes that begin in the cell, the showers, the laundry, the mailroom, the yard. Here you will discover those who go over the wall, under the wall, through the gate. Here you will see helicopters at work, or transit vehicles brought to a halt. Here you will find the planned escape, as well as the opportune escape. And you will witness the escape of the loner who does not require the involvement of others – or that of the escapee who requires help from fellow inmates, or from an insider, like a corrupt officer providing tools or weapons. Or from the friends and relatives who smuggle in requested items, or provide getaway cars.

Any notion of strict categorisation does not work, for the encyclopaedic method hinders readability. One slight regret is that I had to cut back for the sake of length, to take away some of the details of the planning, the frustration, the perseverance noted by the escapees themselves, even if the sheer number of cases does convey a further dimension. It has not been my job to plot every move until recapture … or, indeed, the lives afterwards of those who are not recaptured.

One of the remarkable factors to emerge time and time again is the amount of care, attention and energy given to an escape, only to see it fizzle into a sketchy series of possibilities once the escapee gets his leg over the wall. Not everyone has plans, beyond the plan to get away. They may not know where they will hide, where they will run to, or how they will continue to stay out. Some, as noted, are really only going out for a short break, perhaps only intending to see their families, knowing they will be quickly recaptured. Some have money available from their crimes to flee abroad, for there are still countries where no extradition treaties are fully operational. For many years it was the Spanish coastline, the ‘Costa del Crime’, although that is not officially the case today. But extradition has not been retrospectively applied, and it is still a popular residence for escapees – probably because they can blend in more easily amongst the world of former criminals, as well as the general British contingent of ex-pats.

The use of the masculine ‘he’ is quite noticeable too, for all but a few escapes are by men. This is no gender bias on my part. I have included the few women I unearthed, though I could probably have found others. However, the intent was not to excavate for the sake of it, but rather to demonstrate the breadth and the resourcefulness of the escapees. Whilst I focus on some because of their distinctive aspects, I offer others to provide context. Likewise, whilst this study draws from a wealth of British cases, I give some perspective on other escapes from all around Europe and the rest of the world.

And whilst I didn’t want to delve through history in any great depth, I felt that a handful of comparisons from the past would add another dimension. To escape today, in a practical sense, is very different from escaping thirty years ago – let alone three hundred years ago, even if, on another level, it is still the spirit of Man that is making that bid for freedom.

This is not an endless list of escapes all subjected to the same degree of analysis. What I wanted was to show the sheer bravado, the courage, the daring, that comprises the strength of the human spirit, which is to be cherished. And yes, I am aware that there are escapes that have led to further murders – indeed, I was horrified by some of the events as I read through them. But it is the spirit of Man that I am celebrating, through all his triumphs and adversities, without which mankind may well not survive.

I have refrained from getting too technical by categorising prisoners as A, B, C … or the varying levels of risk classification, as ‘standard escape risk’, ‘high escape risk’ or ‘exceptional escape risk’, as these have changed over the years and across the different countries. In general, those who feature are prisoners who have escaped before and have the ‘escape risk’ label attached to their name, if not to their prison apparel. The term ‘E-list’ – ‘escape-list’ in UK Home Office terminology – is not intended as a restricting or defining term, as the ground covered goes way back before such official terminology was employed. However, these are all people who would have been on an ‘E-list’, people who made it their aim, or in some cases claimed it was their duty, to escape.

Though I am drawing on many angles for my information, the viewpoint that interests me the most has to come from those who have experienced escaping from prison. Whether their crimes are seen as horrendous, or more mainstream (albeit perhaps major); whether we have admired them for it, or been aghast at their further offences. But, at the end of the day, we, as readers, were not there, did not experience the fear and violence that stemmed from some of these men’s actions. As Tommy Wisbey’s daughter, Marilyn, notes in her autobiography, it’s very romantic to read about them, but if you are in the midst of a robbery, whether being committed with guns or coshes, you never know if those weapons are going to be used.

This may come across as an intense book, because I’ve tried to trim away some of the frills; yet, at the same time, I wanted to preserve some of the character of those involved. There are no rules as to what I left in and what I took out. My desire was to keep you reading, to view the tragedies along with the humorous aspects, to add probable annoyance as well as offering possible justification.

But I did want to lean toward the side of the escapee, though not for any moralising purpose. Most criminals are not proud of being criminals. Some had a raw deal. Most knew what they were doing. That is not my concern. I wanted to give their stories because they were the ones locked in a cell for years on end. Many gave every waking hour, unless distracted, to focusing on escape.

We may pass comment on the neighbour who locks their dog in a kitchen whilst they go to work. We might empathise with the poor beast whining away. And yet we don’t want to give much thought to the human being who is locked away, and who does not make much noise … or, if he does, we find ourselves unsympathetic. But if you condemn this man, then you condemn part of your own spirit.

The idea of escaping, or absconding, from prison – or indeed any form of custody, like transport vans, police stations, law courts – has been etched into our psyche in modern times by television and cinema, often making the event more spectacular, more thrilling, perhaps somewhat romantic. All the heroes are rugged and handsome, and it is probably no good for the real men in our prisons, who we cannot see – the gangsters, criminals, ‘villains’, hardmen – to be confused with film fantasies. For once they are out of prison, whether by escape or official release, they face the agonising temptation to continue as a recidivist rather than seek legitimate employment.

Walter Probyn turned away from the limelight. He may well recognise that he has become a famed escapee, but he says he was not a competent criminal and shouldn’t be emulated. Unlike many others, Probyn wished his talents could have been developed and put to better use.

Bruce Reynolds (not an escapee himself, unlike some of his fellow Great Train Robbers) has a different perspective: “Perhaps it was like what happens when a footballer or mountaineer comes to the end of their career. They live their entire life on the edge, but what happens when it’s all over, when you have to stop? It was very hard for … us when we quit. When we came out of jail we were old men, and too well known. We knew we had to stop for our families’ sake. But you never stop missing the buzz.” (My emphasis.)

Today’s prisoners are faced with more sophisticated technology to prevent their escape. Everyone knows it will be more difficult. But then, at least one of the escapes in this book occurred less than six months ago as I write. If there is a weakness in the system, then the prisoner who is fixed on escaping, who is watching and scheming, will take advantage of it.

And the greatest weakness will always be the human element, the guards and officials who go about their job in a routine way and who slacken at their peril. Equipment might become faulty, a camera may go on the blink, but it is invariably the guard who just pops off to the toilet, who falls asleep, who engages in convivial conversation and is lulled into a false sense of security, who recurs repeatedly throughout these cases. The people who are employed as guards are hardly likely to be among the brightest, and the probability is that some of the prisoners are of substantially higher intelligence. Television programmes feed us a diet of crime fiction where video cameras are properly maintained and operated, which does not equate with reality. Talk to people who live near a prison and they will tell you that there are periods when escapes over the wall can become quite prolific. Those at fault fight hard to cover up their inadequacies in not having prevented them.

It’s not that many years ago since the Chief Constable of Durham was offering scare headlines in relation to the Great Train Robbers housed in Durham Prison, suggesting these men and their associates would stop at nothing, “even to the extent of using tanks, bombs and what the Army describes as limited atomic weapons. Once armoured vehicles had breached the main gates there would be nothing to stop them. A couple of tanks could easily have come through the streets of Durham unchallenged.” How flattering to the convicted men. One has the impression that the police chief was starring in his own movie: “If that happened there would be a pitched battle and a lot of people would be killed.” He could have appeared alongside Robert Duvall on the beach in Apocalypse Now. Soldiers were posted with fixed bayonets. Extra police patrolled with dogs. But nothing materialised. No helicopters came swooping in. And he said he was trying to strip the criminals of their glamour!

In the first chapter, with Charlie Wilson, I’ve given greater detail to create some sense of the atmosphere and the conditions. But it has not been my intention to give all the details all the time. I have created rules, and I have transgressed those rules at every turn. I make no apologies. Books have been written by escapees like Hinds and Probyn not only to relate their habitual escapes, but also to explore the reasons behind them. This book has to make their cases brief in order to encompass many others. Some names have become famous by virtue of one escape, whilst others, like Patsy Fleming and Georgie Madson, are regularly mentioned but rarely given coverage. (Perhaps they were pleased to be out of the public eye, as it could have been an obvious hindrance at the time.)

Sometimes one has to suspend belief at some of the details, for fact has often been more extraordinary than fiction. Reading about some of those who appear within, notwithstanding some of their crimes, the spirit of these people in escaping from incarceration has been far more inspirational than any of the splurge of biographies that our celebrity culture pours out daily.

But our age of celebrity affects villains as much as anyone else. They are no different. The criminal is as much a part of society as a film star, a politician or a lawyer. (Or even a debt collector.)

The master escapologist Harry Houdini is the perennial reference point for everybody who escapes more than a couple of times from prison, and who, like Houdini, is working at the limits and does what seems to be the impossible. But, just as most of us couldn’t imagine ourselves as a Houdini, we also cannot begin to imagine being placed in prison for twenty years. You know that all of your life will change in that time; if you have family, and they stick by you, they too will have changed in ways you may not even recognise; the children will have grown up and left the nest … You will want to escape, even if the chance to do so is negligible. But where to go? Even with money stashed away, who is prepared for this? Are you?

But it is no good us sentimentally thinking we can feel for the prisoner. Or even feeling sorry for them. Most criminals know the risks they take, know the punishments, know that, if they get recaptured, they’re going to be beaten up and mistreated by the guards. Because they’ve been beaten for less in the past, particularly if they have a reputation as a hardman.

Today we read about the imprisonment and rape of Elisabeth Fritzl by her father in Austria, and think of the horror of twenty-four years underground, or of Natascha Kampusch, the Viennese schoolgirl who was kidnapped, aged ten, and held for eight years in her captor’s garage before her escape. We think of the terror that they were submitted to, both physical and mental, but we barely equate any of that with being in one of society’s prisons. For prisoners are there through some fault of their own, and, of course, some prisons are more lenient than others.

But any prison is a prison, though some are worse for all types of reasons – whether it is the physical conditions of the place, the level of restrictions, the management and officials who guard the inmates, or the brutality. For we cannot identify with the brutality as a whole, on every level, unless we have actually been there.

It should be pointed out that there is still some confusion over data with some cases, and, despite endless checking of conflicting reports, it is not always feasible to sort fact from fiction, truth from lies or fantasies. Indeed, some accounts have probably gone beyond the bounds of ever being resolved, as myths have become reality. In some places I’ve made the variations plain, and in at least one case I’ve made what left me incredulous read as incredible. But, generally, the other points don’t affect the modus operandi of the escapes, which is the point of this book, after all.

No one side is ever correct when collecting information. The official versions from within the system are as capable (if not more so) of fudging, erasing or misleading as the criminals themselves. Each side has different things to hide at some time or another, or different individuals to protect.

But because testimony comes from the criminal side, that does not make it ‘black’ to the police’s ‘white’. How could it? (I was brought up in a house, where I am now sitting, not a stone’s throw from the former home of a Flying Squad officer who was jailed for corruption in the 1970s.)

In prison there is often little to do but talk. So they tell each other stories, invent a little bit, or change the bits that weren’t as good. And later, perhaps, they forget what is real and what is fabricated. It happens to everyone else, so why not to criminals? Why should all that you read here be the truth? Whose truth? The media’s? Authors like me, who pen it? Or the villains who lived it, who may still wish to write down the truth but find that they can’t? Somewhere amidst this sea of anecdotes there is a mass of exciting life stories … and many sad ones. But all these stories have been lived, and paid for, the hard way.

I concur with the French director Barbet Schroeder, who recently said of his film Terror’s Advocate, “When I am doing a documentary I want the freedom of fiction. I cultivate everything that is fiction … People often think documentary is truth. Obviously, it is not. The minute you choose one shot instead of another you are entering fiction.”

Despite the idea that to escape from prison is to leap into freedom, it is rarely forever. The more one reads of the cases, the more one knows that, even if the escape is meticulously planned and successfully carried out, the freedom gained may well be short … often only hours, if that. And one senses that the escapees know it too, even as they bid for their freedom. To escape brings with it all manner of problems; problems that may make many question the worth of such a tremendous effort. As is so often the case, one may well be replacing one prison with another, sometimes in the shape of one room, always watching one’s back, fearing betrayal or worse. And yet to bid for that freedom, even with all its doubts, highlights how our very spirit and essence as human beings is otherwise at stake.

So what does one say to Walter Probyn, with his very singular attitude? “You don’t need a lot of patience to plan an escape because you’ve got nothing else. Something like that is something to cherish while you’ve got it, it’s a labour of love, something you really enjoy doing so you take your time doing it. It’s like a hobby.”

One final thought.

Throughout my research, I continually read of enormous leaps from one building’s roof to another, or from one roof to another on a lower level. Having the opportunity to wander around a block of flats, I ventured onto building tops, estimating similar gaps, similar leaps … and wondered not only how brave, or how stupid, one would have to be to accomplish it, but how anyone could land without breaking bones, let alone twisting joints, even if that person was fit and knew how to roll on impact, assuming he cleared the distance in the first place.

Ankles broken, wrists sprained, backbones jarred, not only from leaps, but from drops over the walls – all these feature here, along with those who make it unscathed. Don’t underestimate what is required to make those death-defying leaps across gaping spaces, or those heart-stopping drops down the sides of high walls.