Читать книгу Collectors - Paul Griner - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE CHURCH BELLS STRUCK THREE for the hour, then began ringing in celebration, so loudly that at first it was impossible to talk, and outside the church it was hot and windy. Dust blew down the street and over all their heads, the women’s dresses clung to their bodies, Claudia’s veil was billowing. It whipped in her face, distracting her, and then her cousin Jean appeared in the line, looking collected and cool despite the wind and the midday heat, wearing a sleeveless mint-green dress and heels. Under her arm was an elegant bag. Claudia clasped her to herself briefly, intrigued but not surprised to detect the scent of Fracas—her own perfume—and then passed Jean on to Boyd, her new husband.

“And this is my cousin Jean,” she said, her hand on Jean’s bare shoulder.

Boyd had been talking to the blond in front of Jean, flirting really, and now he turned to Jean and tilted his large head to the side. “Sorry,” he said. “I didn’t catch your name.” Smiling, he took Jean’s offered hand in both of his.

He was beefy and broad, but his touch lacked force, and even at his full height, Jean guessed, he wouldn’t be as tall as she. She straightened and felt Claudia’s fingers leaving her skin one after the other, like a string of pearls being plucked from wax, and forced herself to speak.

“Jean,” she said. “Jean Duprez.”

Boyd had already glanced beyond her. She watched him prepare his vague smile for the next person in line and noted that the mention of her full name did not spark his interest. She wasn’t sure what she’d expected—a raised eyebrow, a look askance, mock horror, a wink—something, she supposed, that would indicate Claudia had spoken to him about her, but he gave her hand a pallid squeeze and she moved on.

Bland, bland. How could her cousin have married him? Well, it had been years since they’d spent time together; perhaps Claudia was vastly different from the fierce girl she remembered. Her heel caught and she glanced down at the gray cobbles, the rivers of crimson rose petals running between them. Children had been placed across from the bride and groom in a shaft of sunlight, throwing the petals at all the well-wishers; a few blew around her ankles and one clung to her calf.

Someone was standing beside her, waiting for her to go on. A man, she noticed, tall and dark-haired; he seemed to be staring.

The church bells were still ringing, passersby in cars were waving and calling out their congratulations; a flock of pigeons flew low overhead, cooing, their wings beating with a sound like fluttering fabric, and Jean watched them, the way their iridescent necks shone in the sun, until she lost them as they arced around the steeple.

Ahead was the minister, tomato-faced and smiling, and beyond him Sally, Claudia’s mother—Jean’s aunt. Happiness had the odd effect of making her ugly, it seemed; her face was tear-stained and swollen. She busied herself with a bow at the side of her fussy dress as Jean approached, and Jean thought Sally planned to snub her, but at the last moment Sally turned and gave her a quick, false smile.

“Jean,” she said. “So Claudia did invite you.” Her voice was full of the old Gallic chilliness, but even aimed at her, Jean found its familiarity oddly reassuring.

“Yes. So nice of her to remember, wasn’t it?”

“What beautiful shoes,” Sally said, looking down.

“Thank you.” Jean lifted one foot and tilted the shoe into sunlight. “Unusual, don’t you think? And amazingly comfortable.”

“And so last year,” Sally said. “I can tell by the straps.” Jean swiftly reached the end of the line.

The reception was at Sally’s lake house, with its broad, sloping lawn, where the lush grass was as soft as powder beneath Jean’s shoes, and teal green in the canted afternoon sunlight. A waiter crossed the grass in front of her, holding aloft a silver tray of champagne flutes, the glasses flashing in the sun, and Jean plucked two as he passed; cornered by someone irritatingly persistent, she could wave the extra and claim she had to be off. She drank half of one, then slipped through the shrubbery to the shore, thinking that to Claudia, at least, the wedding must have seemed a grand success. It was warm and sunny, people were dancing and laughing, and all along the water a sinuous band of fruit trees were in bloom—crabapple or cherry, Jean thought—their pink blossoms pale against the black bark of the trunks. Very late this year; it had been a cold spring.

By the shore stood two men, a boy of about eighteen wearing a rolled blue bandanna as a headband and an expensive but stained suit, and beside him, on a rock, a middle-aged man in bare feet and khaki shorts, wearing a mocha-colored velvet tuxedo jacket. Both were smoking cigars. She thought they looked foolish, trying too hard to be hip, and it amused her to watch and judge, since she knew almost no one at the wedding, and those she did, she remembered only distantly, from the seemingly endless hours she’d spent along this very shore as a child.

She and Claudia had played daily when they were younger, until they were twelve; their names for each other had been She and Me. Then their parents stopped seeing one another, some argument she barely remembered concerning the two of them, the obsessive nature of their play, their made-up language. It had been an irrevocable break, and now, years later, her cousin had written to her out of the blue and announced she was marrying and wouldn’t Jean please come? It would mean so much.

And so here she was. They’d barely had time to say hello, though Jean arrived an hour early for the service, and now the reception was halfway over. Checking her watch, she decided it would be another hour before she could leave gracefully, and when she looked up she glimpsed her aunt’s blue dress passing behind the white and coral azaleas, the dress such a beautiful blue, Jean thought, one hardly noticed the gray in Sally’s hair against it. She seemed on her way somewhere, as she had all afternoon; the caterers needed checking up on, perhaps. Weddings weren’t for the bride and groom, of course, but for their parents, and Sally was ignoring Jean completely and Uncle Teddy was dead, and Boyd’s parents seemed merely happy to be there, as if they hadn’t quite believed Boyd would pull this off. Boyd. She drank more of the champagne. Even his name sounded foolish.

The cigar smoke from the men beside Jean was heady, too strong, really, but in the warm sunshine she found herself attracted to it and moving closer to its source. Soon her allergies would kick in: her temples would throb, her eyes fill with water, and every breath would become a struggle, but for now the scent was pleasurable. She listened to the buzz of the quiet conversation and wondered briefly if the two men might be her distant relatives, if she’d seen them years ago at family Christmas parties, perhaps made fun of them with Claudia. One year she and Claudia had carved the initials of all their least favorite relatives into her aunt’s kitchen wall, a task that had taken half an hour.

Music and echoing laughter reached her from over the water, and she turned to watch the approach of the barge with the bride and groom and many of the guests. They had gone out on it earlier, and now they were dancing to the tunes of a jazz trio, women in pastel dresses floating in the arms of tuxedoed men, their bright, indistinct faces uniformly happy. Jean searched for Claudia and Boyd in the crowd. The barge was right in front of her, at the midpoint of its orbit around the lake, so close she could see the rust-red paint peeling on its hull and hear the quiet chug of its engine below the strains of the music, but even so she couldn’t make out the bride and groom. They must have been hidden in the center of the throng, the core of happiness around which the happiness of others gathered, like bees around a honeycomb. Listening to the waltz, an up-tempo number she recalled from dancing lessons long ago, boys’ sweaty palms clasping her gloved one, she regretted her decision to stay ashore.

“It wasn’t a choice, really,” she said, to comfort herself, and when the middle-aged man standing on the rock glanced up and smiled around his cigar, she realized she’d spoken aloud. At work it didn’t matter, there they were used to her ways, but among strangers the habit embarrassed her. She felt the rims of her ears redden and finished the first glass of champagne, then turned to face the lake.

She had since childhood harbored a vague foreboding about deep water. It had not kept her from learning to swim, but when she’d been asked earlier to go on the boat it had held her back as surely as a physical restraint, yet she’d made a choice, she knew that. Everything was a choice. Ashore there was champagne, and a long meal of chilled gazpacho and grilled shrimp and smoked salmon, and the buzz of slightly drunken conversation all around her, and she’d chosen safety and satiety over the press of a stranger’s hand, urging her to come aboard and dance, though she wouldn’t have, younger. She and Claudia had never opted for security as children. They’d squirted trails of lighter fluid on their forearms and lit them; dropped bricks ever nearer to their bare toes from higher and higher, eyes closed, aiming by feel and not by sight; ridden their bicycles down steep, curving hills in utter darkness, their bare, dirty feet propped on the handlebars in order to keep from braking. But all of that seemed long ago.

She worked to dislodge a rock from the shore with the toe of her shoe, continuing at it even after scraping the leather, and toppled it into the water, where the dropped pink blossoms from the fruit trees bobbed in its wake.

Sensing movement nearby, she looked up to see the boy with the headband detach himself from the man, and as he neared, his eyes rose only to her breasts. Her Inappropriate Date Magnet appeared to be on at full force, and she did not bother to stifle her sigh. The magnet had been off, briefly, when she’d been asked to go out on the water, and turning down the stranger’s invitation had been foolish. This proved it.

He took the cigar from his mouth, its end sodden and horribly misshapen, as if it was something dredged from the bottom of the lake, and she felt like asking if he knew he wasn’t supposed to eat it. When he smiled at her, showing nice teeth, sex was clearly on his mind, but judging by his swagger, it would be of the quick and unmemorable kind.

“Someone as lovely as you shouldn’t be lonely,” he said, “today of all days.”

“I’m not lonely,” she said, “just alone. And someone as old as you ought to have a better line.”

He blanched, and she realized how she must have sounded, the scolding, dismissive edge to her anger, and she felt a momentary pang of regret, but then she decided she shouldn’t care. He’d approached her uninvited, after all, and not the other way around, and the proprietary air he exuded was annoying. Still, it was a wedding, people were in a festive mood. She raised the second champagne flute, still full, by way of explanation. “I’m waiting for someone,” she said, hoping to sound diplomatic.

“Obviously not me.” His face had lost its color, and his voice was rising to a whine, which irritated her.

“Obviously,” she said.

When he turned back, he was so angry that she could almost hear him ticking.

The man relighted the boy’s cigar and they leaned together and began to talk. She heard the slight hissing of their words, a snatch of laughter, something guttural like a grunt, and then the man sneered and shook his head. They were discussing her, her skin prickled with the knowledge, and the air in her lungs suddenly thickened, as if she were breathing mud.

She strained to hear the waltz as the barge moved away over the water, but the boy’s voice grew louder, almost boasting, and when the man said something to make the boy tilt his head back and laugh and then stared at her over the boy’s shaking shoulder, she knew what would happen next; men in pairs were so transparent. She had always hated that, the pack mentality. He slapped the boy’s back and came toward her.

It angered her. She hadn’t asked for this, why couldn’t they let her be? Nonetheless she gave him the full radiance of her smile. She knew it worked; years before, one of her doctors had suggested she smile more. It’s free, he said, and inspires people to like you. But I don’t want them to like me, she’d replied. I want them to leave me alone.

“I hope my nephew wasn’t rude,” the man said, holding out a hand. “Austin Harding.”

“How do you do.” She let him hold her hand longer than required, and when he noticed that, he stepped a foot closer. It did not surprise her that his cologne was Brut, or that she could smell it even over the cigar.

“Don’t you think it’s a perfect evening for a walk?” he said, pointing the cigar at the far end of the lake.

“A walk would be just the thing,” she said.

He started along the shore, bare feet padding on the stones, and when she didn’t follow he turned back to her and smiled. “Coming?”

“No. I was hoping you’d just walk away.”

Before he could reply, she drained the second glass of champagne and began moving up the lawn, putting a stand of fragrant blooming viburnum between them. In case he followed, thinking of his bare feet, she dropped the flutes in the trampled grass.

A bridesmaid in a lemon-colored dress was talking to an usher, their faces red in the late-afternoon light, and Jean watched them from across the lawn, seated on the grass, the skin across her cheekbones tight from the day’s sun, her eyes tired. The woman moved back and forth in front of the usher, talking, animated, and now and again the man nodded or shrugged, but mostly he was impassive, and when he spoke, his responses seemed monosyllabic. After a few minutes the bridesmaid left him, but before going she held up one finger, wagged it, and put her other hand out, urging him to stay. The third time she did it he nodded.

When the bridesmaid returned, holding two white coffee cups on their saucers, the man was gone. She swiveled her head from side to side, then rose up on her toes trying to find him, without luck. Soon she approached another usher in his swallowtail coat and offered the coffee to him.

A man came and stood beside Jean.

“Pitiful, isn’t it?” he said.

Jean could not make out his face, as the sun was just above his shoulder, but she gathered he was speaking about the bridesmaid. She wished she hadn’t laid her hat beside her on the grass; putting it on now would be too obvious. As it was, she could look no higher than his chest.

“It is rather sad,” she said, glancing back across the lawn. The usher held up his hand in refusal of the coffee, and without a word the bridesmaid spun away. A third usher, balding and ponytailed, was making his slow way toward the porch, and the bridesmaid moved to overtake him.

“I suppose if I wore a swallowtail coat, I’d be more popular,” the man said to Jean.

“Would you really want to be?”

The man laughed. “No. I think not. That coffee’s got to be cold by now, and I can’t imagine the conversation is much better. Have you heard her voice?”

Jean said she hadn’t.

“She sounds like Gomer Pyle’s sister.”

Jean shielded her eyes, trying to see his face, and when he shifted, the long straight line of his nose became distinguishable. She had the odd, passing sensation that he enjoyed watching her struggle, which irritated and intrigued her, and she was about to ask him to move when he crouched beside her, steadying himself with one hand on her knee. She still couldn’t see his face. When he ducked she’d been left staring into the sun, and now she had to close her eyes and turn away.

“You’re Jean, Claudia’s cousin.” It was not a question. “Steven.”

“Steven.” On her closed eyelids she saw a single burning sun, yellow against a black background, which after a few seconds bisected into two black balls, the area around them turning orange. She squeezed her eyes to clear her vision.

“Steven Cain.”

She opened her eyes and looked at him. The name meant nothing to her, of course, though she didn’t let on. He held his hand out, shook hers firmly, then dropped it back on her knee, and she liked that, the ease of his affection. His hand was warm and dry and lighter than she would have guessed, as if it were stuffed with feathers, but his touch felt vital and electric.

“Claudia’s told me quite a bit about you. I hope you won’t think me too forward. You’re the one person I hoped to meet from the entire party.”

“How flattering.” She meant it, pleased that Claudia had spoken of her, and she became aware of her dress clinging to her chest and thighs in the heat, as if the day had suddenly grown hotter. She breathed deeply to calm herself, taking in the smell of crushed grass and the scent of his cologne, which was unusual, a blend of smells and colors, cinnamon and sienna and burnt amber, she thought, something ancient and earthy and enduring. The exoticism made it attractive. His shoes were tightly woven flats, made of buttery leather.

“Good thing you found me now,” she said. “I’m afraid I was getting ready to leave.”

“Yes, I thought you might be. I let it go rather too long, didn’t I?” He shook his head at his own foolishness. “I knew if I didn’t come over now I’d lose my chance.”

“You don’t seem the shy type.”

“Oh.” He waved dismissively. “I’m not.”

When he lifted his hand from her knee it was as if her skin had been peeled away, she felt suddenly exposed, and she wished he’d put it back.

“To be honest,” he said, shifting his weight from one leg to the other, “I was watching you for a while.”

“Oh really?” She slid her hands down her calves and grasped her ankles, folding herself in half. Her cheek rested on her knee, where the smooth skin was still warm from his touch.

“To be sure.” He nodded, looking out over the lake, the bright plane of copper-colored water. “Claudia said you were unusual, but one never knows.”

“You mean, I might have been like that bridesmaid.”

“Exactly.”

Now it was her turn to laugh. She leaned back on her palms, wondering how long he’d been watching, and what exactly he’d seen. “And I passed?” She worked her fingers into the warm grass until they reached dirt.

“Certainly. I should have trusted Claudia.”

From beside him he produced a glass of champagne, strings of thin bubbles rising to its surface.

“I’d offer to get you one,” he said.

“But you’re afraid I’d leave?”

“No.” He sipped the champagne, and she watched his throat move as he swallowed, and then he pressed the glass into the grass near her feet. He seemed to inspect her shoes, the complicated straps enveloping her arches and ankles, the scrape across the right one. “I’m sure you wouldn’t. I believe everything Claudia’s told me is true. You’re an only child, like Claudia, and you two share the same birthday, don’t you, like twins?”

Jean nodded.

“So you’re not a flirt. She said you wouldn’t be. But you will be leaving the party soon, and you don’t want to get hurt. You have to drive.”

“And you don’t?”

“I’m an overnight guest.”

“A slumber party. I didn’t know. I’d have wangled an invitation.”

He pulled back a bit, as if offended, and tensed his jaw, but she wasn’t sure what she’d said wrong; beginnings were always so rocky. Of course, she’d found that endings could be even worse: Oliver Brisbane had called her for five or six months after she’d broken up with him, discovering her number each time though she changed it continually and had it unlisted, and always he left the same message, “Brisbane calling. I’ll try again.” Eventually he’d given up, but by then she’d met Pavel Hammond, whom she thought might be the one, until the night she’d awoken to find him sitting on the floor beside her bed, watching her sleep, the planes of his angular Slavic face distinct, pale wedges in the dark. He’d climbed the fire escape to reach her.

She shivered at the memory, those tiny, dark eyes, then touched Steven’s arm. “You must live a long way off.”

He drank the rest of his champagne, observing her hand on his arm, and put the glass down beside her calf. She realized she’d been watching him closely, studying him, really, because she sensed that she could not afford to make a mistake this time. At last he stood, and from his face he seemed to have reached a decision.

She shielded her eyes again, looking up at him, her pulse throbbing at her temples and throat. His hair was short and very black, but she couldn’t see his eyes, and she still didn’t have a good mental picture of his face. She did not want him to leave.

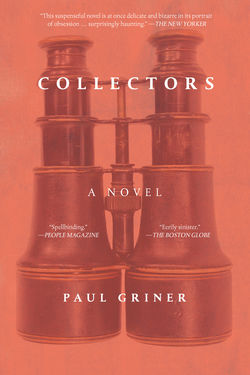

“I live nearer the city.” He produced a small pair of nickel-plated binoculars from a jacket pocket, turned them over in his hands, and pocketed them again. “I have a boat.”

She looked toward the docks, the swaying, forested masts, where halyards were clanking against the aluminum and a few gulls sat perched high up among the flapping pennants and flags.

“Not here. On the ocean, just north of Boston. I’d like you to come out on it with me. Do you sail? That’s the one thing Claudia didn’t tell me.”

Her stomach hollowed at the thought, just a few boards between her and all that water, but she did not allow herself to contemplate it, or why her desire for his presence reminded her—vaguely, but insistently—of other desires she could not at the moment name.

“I haven’t sailed,” she said. The briefest of pauses, she barely knew him, yet Claudia had spoken to him about her, and he had sought her out. “But I’d love to.”

“Good. You’ll hear from me next week, then. I look forward to it.”

“As do I.”

He bent over her. Perhaps he would touch her shoulder; her skin tingled in anticipation, and she believed she could distinguish each freckle and pore, and that, after, she’d be able to recall the exact spot on which his fingers had rested.

But he straightened. “You’ll be a natural on the water.” With his shoe he tapped the glass he’d left behind, making it ring. “You might take that, in case anyone else bothers you.”

That he’d been watching her so long surprised her. She’d been about to give him her phone number, which was unlisted again, but by the time she recovered he’d turned and walked away. She started to reach out after him, stifled the gesture, took up her hat, stood, and smoothed her dress while she watched him go.

The wedding photographer had come upon them and snapped a few shots. He caught the motion of her reaching hand, and though Jean never saw the picture, Claudia did, yet it was the one he’d taken earlier, just before Steven stepped away, that Claudia would always remember. It showed the two of them in profile, Jean seated on the grass and Steven looming above her, the long swell of the lake rising between them, their faces blotted out by the sun. The barge with the dancers had just floated into the top of the frame, black because it was backlit, and it seemed to be a mistake in the photograph or a flaw in the negative, a dead spot. This was the one picture from her own wedding that Claudia never forgot.

She threw out the print early on, even before her divorce, but its image appeared to her quite often, especially during the warm days of late spring when the spicy vanilla scent of viburnum drifted into her open bedroom window and the afternoon sunlight slanted across the maple floorboards, turning them a butterscotch orange. At night, dreaming, she saw herself taking the picture, though of course that was impossible. When it had been snapped, she’d been far out on the lake, dancing over the placid water.