Читать книгу Dostoevsky's Incarnational Realism - Paul J. Contino - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Beauty and Re-formation

ОглавлениеEarly in the novel, Mitya confesses to Alyosha: “I always read [Schiller’s] poem about Ceres and man. Has it reformed me? Never! . . .” (96). But if we look at the scene more closely, we do see signs of Mitya’s reform. His confession—which next draws on Goethe—becomes a prayer, a bow to God: “Let me be vile and base, only let me kiss the hem of the veil in which my God is shrouded. Though I may be following the devil, I am Thy son, O Lord, and I love Thee, and I feel the joy without which the world cannot stand” (97). The beauty of poetry propels Mitya’s desire for metanoia, and a recognition of his continuing capacity for joy. Robert Louis Jackson puts it well: “Precisely in his keenly felt sense of ignominy, . . . in [Mitya’s] moral despair at what he discovers in himself and in man, lies the measure of the possibility for change” (Form 64). Mitya’s encounter with poetic beauty—and the ideal to which it points—elicits his sense of sin and still-inchoate resolve to change. “An apparent enthusiasm for the beautiful is mere idle talk when divorced from the sense of a divine summons to change one’s life” (Balthasar, “Revelation” 107). Mitya senses this summons. By the end of the novel he will give it moral and spiritual form as his “consciousness of a new man within himself is accompanied by an aesthetic awareness of himself as an ‘image and likeness of God’” (Jackson, Form 65).

Mitya faces many challenges, and one of them can be found here, in the way he bifurcates beauty into two “ideals”—one divine, one demonic. He desires the human person to be less “broad” in his capacities, but in achieving that aim, would remove flesh from spirit, and thus cripple his apprehension of beauty’s analogical potential. Specifically, he doesn’t yet recognize the sanctifying potential in his desire for Grushenka:

Beauty is a terrible and awful thing. . . . I can’t endure the thought that a man of lofty mind and heart begins with the ideal of the Madonna and ends with the ideal of Sodom. What is still more awful is that a man with the ideal of Sodom in his soul does not renounce the ideal of the Madonna, and his heart may be on fire with that ideal, genuinely on fire, just as in his days of youth and innocence. (98)

Mitya rightly retains the ideal of Mary, the Madonna whose free consent made possible the incarnation. But his emphatic “either/or” severs the saintly receptivity modelled by Mary—“Let it be done to me according to your word” (Luke 1:38)—from human eros. He imagines an internal war in which spiritual beauty (represented by God) battles the beauty of fleshly form (represented by the devil): “The awful thing is that beauty is mysterious as well as terrible. God and the devil are fighting there and the battlefield is the heart of man” (98). For the gnostic or Manichaean, the battlefield presents armies equally matched. For the Christian realist, the Creator remains invulnerable to the wiles of demons, who are, after all, creatures. Out of love for creatures, the Creator enters bodily, created reality and thus hallows it. The person, made in the Creator’s image and likeness, can exercise freedom, and draw upon the Creator’s grace to do so fully. Christian realism is incarnational: body and soul are integrally related; desire can be well-directed or dis-ordered. Rightly, Mitya rejects the lust and violence captured in the image of “Sodom.” But his desire for Grushenka—who is very much on his mind in this discourse with Alyosha—can’t be reduced to “Sodom.” Sodom surfaces when Mitya reduces and reifies her personhood to her “supple curve” (107). Misapprehending her personal reality, Mitya allows himself to be consumed by lust and the disordered rage he imposes on his father Fyodor and others: Snegiryov, Ilyusha, Grigory. Even after he becomes a “new man” and has “taken all [of Grushenka’s) soul” into his own (501), he becomes jealous when she’s kind to other men (477).

Mitya remains human, a work-in-progress. But through his difficult descent into finitude—still in process at the novel’s close—he slowly learns to integrate eros and agape. Even in his marriage with Grushenka, he will find beauty’s most “mysterious and terrible” (98) form in the “precious” (276), kenotic image of Christ.83 His marriage will entail a cross of its own; he does not “run away from crucifixion” (502) in his commitment to the woman whom he passionately loves and will serve as a husband. “The humiliation of the servant only makes the concealed glory shine more resplendently, and the descent into the ordinary and commonplace brings out the uniqueness of him who so abased himself” (Balthasar, “Revelation” 114).84 Mitya comes to accept his particular cross through a “descent into the ordinary and commonplace”—flight to America—as I will elucidate fully in Chapter 5.

Mitya provides one example of the way the novel imagines Christ as the novel’s paragon of transformative beauty. In the 1854 letter mentioned in the previous chapter, Dostoevsky declared that he knew “nothing more beautiful” than Christ.85 He then boasted: “if someone succeeded in proving to me that Christ was outside the truth, and if, indeed, the truth was outside Christ, I would sooner remain with Christ than with the truth.” Twenty-five years later, as he wrote The Brothers Karamazov, he saw no need to pose such a hypothetical: here Christ, and all that he stands for, coincides with the truth. With full artistic freedom, Dostoevsky “powerful[ly]” challenges Christ’s truth through Ivan and his Inquisitor (“Notebooks” 667).86 But read as a whole, his final novel fully reflects his faith in the Word made flesh, in Christ who calls persons to conform to the beauty of his image.87

The Beauty of the Icon

The Christian tradition has long understood “beauty” to be one of the names of God.88 Along with goodness and truth, beauty forms a trinity of “transcendentals” intrinsically related with each other and their source in “the hidden ground of love.” As they developed the doctrine of Christ, the church fathers emphasized this interrelationship:

Corresponding to that classical triad, though by no means identical with it, is the biblical triad of Jesus Christ as the Way, the Truth, and the Life, as he described as having identified himself in the Gospel of John (John 14:6). . . . As one ancient Christian writer [St. Gregory of Nyssa] had put it in an earlier century, “He who said ‘I am the Way’ . . . shapes us anew to his own image,” expressed as another early author [Gregory of Nyssa] said, in “the quality of beauty”; Christ as the Truth came to be regarded as the fulfillment and the embodiment of all the True, “the true light that enlightens every man” (John 1:9); and Christ as the Life was “the source” for all authentic goodness [Augustine]. (Pelikan 7)

As von Balthasar insists, beauty can never be separated from “her sisters” goodness and truth without “an act of mysterious vengeance. We can be sure that whoever sneers at her name as if she were the ornament of a bourgeois past . . . can no longer pray and soon will no longer be able to love” (Form 18). Denigrated in modernity, Dostoevsky retrieves the beautiful in its integral relation to the good and the true. He depicts its radiance in the visage of those who iconically reflect the beauty of Christ.89

In the Orthodox tradition, the icon reminds the viewer of her participation in divine beauty by virtue of her creation as imago Dei, and the divine call to recover her divine likeness. Dostoevsky’s earliest memory—akin to Alyosha’s—was of reciting a prayer before the icon of the Mother of God (Kjetsaa 1). As an adult, Dostoevsky’s Sunday worship was apparently irregular, although it may have become more consistent in later years, perhaps inspired by Anna’s patient example. But from childhood, he would have known the entrance prayer of the Divine Liturgy according to St. John Chrysostom, in which the priest and deacon “go before the icon of Christ, and kissing it, say: ‘We venerate Thy most pure image, O Good One, and ask forgiveness of our transgressions, O Christ, our God’” (5). An appreciation of the icon can help us better understand the role of beauty in the novel, and specifically Zosima’s insistence that “On earth, indeed, we are as it were, astray and if it were not for the precious image of Christ before us, we should be altogether lost, as was the human race before the flood” (276; emphasis added).

The icon lends tangible, visible form to the trans-figured image of the human person. As theologian Leonid Ouspensky observes, the icon “forms a true spiritual guide for the Christian life and, in particular, for prayer” (180), for “holiness is a task assigned to all men . . .” (193).90 Whether the prayerful setting be communal, liturgical prayer or solitary, devotional, the beauty of the icon calls its prayerful beholder to recover her own beauty, to restore her image—in Russian, her obraz, a word Dostoevsky employs often. The icon fixes the viewer’s attention on that which the incarnation has made possible: Christ becomes flesh—lives, dies, rises, ascends, and sends the life-breath of the Spirit. Through Christ, persons recover their divine likeness. The icon affirms the goodness of the created world, but opens “a window” to the uncreated, infinite kingdom, in which human passions are purified and rightly ordered. The icon represents the beauty of the transfigured Christ and the saints who conform to his image.

In his eighth-century defense, St. John of Damascus emphasized that the incarnation provides the foundational warrant for venerating icons. Christ’s embodiment sanctifies all physical reality. Thus, the icon’s material substance of wood and paint can mediate the divine presence, and the image it represents be venerated, not worshipped: “I do not worship matter; I worship the Creator of matter, who became matter for me, taking up His abode in matter, and accomplishing my salvation through matter. ‘And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us.’ It is obvious to everyone that flesh is matter, and that it is created. I salute matter and I approach it with reverence, and I worship that through which my salvation has come. I honor it” (Divine Images 61). Analogous to the sacraments, the icon visibly, tangibly communicates an invisible, intangible grace. In an Orthodox church the iconostasis between nave and sanctuary represents the heavenly community of Christ and the saints. It charges the liminal space between the congregation and the priest who consecrates the bread and wine in the Anaphora or Eucharistic prayer. The Brothers Karamazov can itself be read as a “narrative icon” (Murav 135) as it points to the person’s eternal telos, even as it recalls and sends her back into this life, with all its mundane responsibilities.

As novelistic creator, Dostoevsky is analogous to the divine Creator. He respects the freedom not only of his “creatures,” his characters, but of his readers as well. Thus the many, varied interpretations of a novel in which those like Zosima and Alyosha, who represent their creator’s values, are powerfully challenged by others, like Ivan. In a letter to his editor, Dostoevsky described the Elder Zosima as “a tangible real possibility that can be contemplated with our own eyes” (Letters 470). One approaches the icon contemplatively, receptively. Dostoevsky hoped the reader might be receptive not only to the “iconic” images of Zosima and Alyosha, but to the novel as a polyphonic whole, and that his final work of art would elicit a free response.91

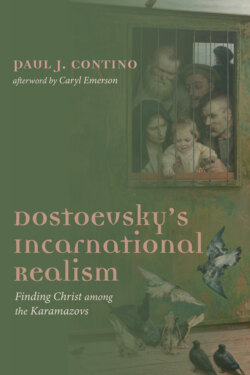

The icon calls its viewer to conversion and renewal: turning, re-turning to God. It calls its viewer to sanctity, to serve as a living icon for others. In understanding this sanctifying process—and its both/and dynamism—I find the sixth-century Sinai icon of Christ Pantocrator (reproduced on the following page) to be uniquely illuminating. This icon was painted in the sixth century, not long after the Council of Chalcedon (451) had forged the definitive statement on the incarnation: Christ is both man and God, finite and infinite, “without separation or confusion.” In it, Christ’s face gazes upon the viewer’s with both gift and summons. Please take a moment to view the icon attentively:

Christ Pantocrator, St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai (used with permission)

Observe the asymmetry of Jesus’ face. From the viewer’s left, Jesus’ face is open, receptive. His eyes gaze into the viewer’s with tenderness, acceptance, and mercy. Here is the redemptive Christ whom Alyosha affirms, just after Ivan’s insistence that no one dare forgive the torturer of an innocent child. Alyosha responds “suddenly, with flashing eyes”: “there is a Being [who] can forgive everything, all and for all, because he gave his innocent blood for all and everything” (213; emphasis in original). But on the viewer’s right side, Jesus’ face seems different: his lip turns slightly down, and his eye seems to judge the viewer and find him wanting. On this side, we are responsible for the violence that blights our world; Jesus’ eye interrogates: what have we done, and what have we left undone? “There is only one means of salvation, then take yourself and make yourself responsible for all men’s sins . . .” (276; emphasis added): Zosima articulates this imperative just before he affirms the “precious”—and salvific—image of Christ. The viewer—and reader—feels a simultaneous release from and imposition of a burden.

We are each responsible to all and for all. Zosima’s refrain, with its emphasis upon the phrase “for all,” draws from the Eucharistic Prayer of the Divine Liturgy:

Remembering this commandment of salvation,

And all those things which for our sakes were brought to pass,

The Cross, the Grave, the Resurrection on the third day,

The Ascension into Heaven, the Sitting on the right hand,

The Second and glorious Advent—

Thine own of thine own we offer unto Thee,

In behalf of all and for all . . . .

(cited by Schmemann, 41; emphasis added)92

“For all”: the phrase is crucial in understanding how the salvific image of Christ is represented in the novel. Alyosha’s and Zosima’s utterances link two complementary claims: first, Christ offers redemption for all; second, we must respond to Christ’s work by working in active love for all.

Christ forgives all and yet we are responsible for all. How can the weight of redemption be removed and imposed at the same time? Zosima clarifies the paradox by pointing to the “precious image of Christ” which stands “before us” (276) as both sublime model and gracious ground. In his invective, Ivan refers to Christ as “the Word to Which the universe is striving” (203). His tone is bitter but his words are true: the Word creates, enters, and sustains the world in all its groaning and travail. Through grace, “in contact with other mysterious worlds” (276), our responsible example may challenge others to go and do likewise. Responsibility entails the work of active love, including the work for justice for the weak victimized by the strong. Grace fosters persevering through that work, and the suffering it often entails. Furthermore—and given Ivan’s description of tortured innocents, this is crucial—suffering retains an integral meaning when understood as a participation in the salvific suffering of Christ (see Col 1:24).

Recall Charles Taylor’s imperative: “We have to struggle to recover a sense of what the Incarnation means” (Secular Age 754). Earlier in his book, Taylor had suggested that a Christocentric understanding of suffering remains a live option, a “divine initiative” available even in our “secular age.” Like Dostoevsky, he recognizes that the invitation can be willfully rejected or willingly accepted:

God’s initiative is to enter, in full vulnerability, the heart of [human] resistance to be among humans, offering participation in the divine life. The nature of the resistance is that this offer arouses even more violent opposition, . . . a counter-divine one.

Now Christ’s reaction to the resistance was to offer no counter-resistance, but to continue loving and offering. This love can go to the very heart of things, and open a road even for the resisters. . . . Through this loving submission, violence is turned around, and instead of breeding counter-violence in an endless spiral, can be transformed. A path is opened of non-power, limitless self-giving, full action, and infinite openness.

On the basis of this initiative, the incomprehensible healing power of this suffering, it becomes possible for human suffering, even of the most meaningless type, to become associated with Christ’s act, and to become a locus of renewed contact with God, an act that heals the world. The suffering is given a transformative effect, by being offered to God.

A catastrophe thus can become part of a providential story, by being responded to in a certain way. . . . (Secular Age 654; emphasis added)

Unflinchingly, The Brothers Karamazov represents a world of “human suffering.” But the Sinai icon illuminates the ways in which a “providential story” can be discerned in that world. Both ancient icon and modern novel suggest that the person who would conform to “the precious image of Christ” must nurture both trust in divine grace and the responsive work of love. To borrow terms from Bakhtin, the icon calls its viewer to respect the unfinalizability of the other person, to retain a hope in the other’s capacity to change, to surprise (Problems 63). But it also insists that persons must embody intentions in concrete, responsible deeds (Act 51–52).

Given human fallibility, such deeds often commence in the action of confessing past faults to confessors. In their deep respect for the personhood of their confessants, both Elder and “monk in the world” are able to integrate the openness promised by mercy with the closure demanded by responsibility. In so doing they mediate “the precious image of Christ.”

Dostoevsky’s Theodrama: The Open and Closed Dimensions of Personhood

Dostoevsky depicts what von Balthasar calls the great “theo-drama” of salvation: gifted with finite freedom, persons are called to respond to God’s infinitely free initiative with either receptivity or refusal, either cross or gallows. When characters resist, the door remains open: the beauty of another’s Christ-like action may inspire a conversion that begins with the resolve to confess.93 In Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, Bakhtin recognizes the “enormous importance in Dostoevsky [of] the confessional dialogue” (262), and observes the way the novelist’s best confessors respect the freedom of those whom they counsel.94 They resemble their author, who refuses to stand in a controlling position above his characters, but treats them as persons, descending and dwelling among them. Dostoevsky “affirms the independence, internal freedom, unfinalizability, and indeterminacy of the hero” (63). But he is not a relativist. He has his own voice (often channeled through his narrator) that “frequently interrupts, but . . . never drowns out the other’s voice” (285). Dostoevsky’s polyphony reflects his incarnational realism: like God, he respects the open freedom of his characters, his “creatures.”

But he is also rigorously unsentimental in depicting the consequences wrought by his characters’ decisions. Like his author, Alyosha respects the unfinalizability of persons,95 but also insists that they must, finally, decide, and accept responsibility for that which they decide upon. Alyosha’s mercy attracts others to him: “There was something about him which said and made one feel at once (and it was so all his life afterwards) that he did not want to be a judge of people, that he would never take judgment upon himself and would never condemn anyone for anything” (22). He takes up Zosima’s mantle, and as a “monk in the world,” serves as a confessor to many.

Alyosha is often compared with Prince Myshkin, hero of The Idiot, Dostoevsky’s earlier attempt at creating a Christ-like character. I see the two characters in stark contrast. Myshkin’s “stubborn reductive benevolence” sees only the open: the inner potentiality for good in others.96 Myshkin refuses to decide between Nastasha and Aglaya and accept the closure of commitment. Myshkin lacks realism, and brings disaster upon himself and others. In contrast, Alyosha is “more of a realist than anyone” (28). He grows in discernment and decisiveness, and thus learns to better assist others who experience anguish in their “freedom of conscience” (221).97 Through Zosima’s example, and his own experiences of failure, Alyosha learns to practice “active love.” He learns to see, accept, and act within the contours of reality. Active love can’t simply be imagined or accomplished in a single, epiphanic moment, “some action quickly over” (270). Of course, at unexpected moments, Dostoevsky’s characters do receive the gifts of sudden illumination and unbidden ecstasy. But active love prepares the ground for such moments—the slow, habitual grind over the rough ground. It tills the soil and sows seeds yet to sprout. Zosima stresses this reality when he counsels doubt-stricken Madame Khokhlakova:

Strive to love your neighbor actively and indefatigably. Insofar as you advance in love you will grow surer of the reality of God and the immortality of your soul. . . . It is much, and well that your mind is full of such dreams and not others. Sometime, unawares, you may do a good deed in reality. . . . Love in action is a harsh and dreadful thing compared with love in dreams. Love in dreams is greedy for immediate action, rapidly performed, in the sight of all. . . . But active love is labor and fortitude, and for some people too, perhaps, a complete science. (54–55)

Active love is hard; it takes time. A person can’t practice it while anticipating applause or obsessing over the fruits of his actions.98 And active love is impossible without grace, as Zosima makes clear: “just when you see with horror that in spite of all your efforts you are getting further from your goal instead of nearer to it—at that very moment I predict that you will reach it and behold clearly the miraculous power of God who has been all the time loving and mysteriously guiding you” (55–56; emphasis added). Like Jesus’ image in the Sinai icon, active love balances the open and closed: it attends to this particular moment with this person (the closed) and remains receptive to the infinite freedom of God’s grace and to the possibility that a small act, in “great time,”99 may eventually bear fruit (the open). The novel depicts this closed yet open reality of active love. As an artist, Dostoevsky represents the reality of “the open” in his polyphonic relation to his characters, and his portrayal of Zosima’s and Alyosha’s ethically exemplary treatment of other persons: persons are finite yet always free to receive the infinite freedom of divine grace. But Dostoevsky also represents the reality of “the closed” by portraying characters who turn potential into actuality through decision and action. Dostoevsky’s balance of both “the open” and “the closed” is integral to his incarnational realism, and is especially embodied in the novel’s dramatic scenes of confessional dialogue which, as we’ll see, Bakhtin illuminates.

Bakhtin was a both/and thinker, with a keen sense of both the open and closed dimensions of human experience.100 His early work, Toward a Philosophy of the Act, developed a philosophy of personal responsibility that emphasizes closure: To act ethically, one must refuse the realm of theoretical system and ideal, inner potential, and embody decisions in imperfect acts. Every day, people face ethical decisions—usually small, occasionally big. Universal principles may apply to such situations, but only with a concomitant sense of particular circumstance. Bakhtin’s early philosophical work draws upon neo-Kantian and Schelerian ideas,101 but his emphasis upon the particular aligns with the classical Christian conception of prudence or phronesis. As discussed earlier, prudence applies universals to the complex contours of specific situations. Bakhtin employs the helpful metaphor of “signature” in describing a person’s responsibility to discern, act, and “sign”—not only for her actions, but also the particular and perhaps painful circumstances that she is simply given. By refusing to “sign,” a person dwells in a static realm of empty potential, fantasizing any number of possibilities. Dwelling in an eternal realm of “maybe” allows nothing to “be”: love in dreams must be embodied in actual deeds of active love. Signature-refusers are akin to Kierkegaard’s aesthete, floating in an airy yet paradoxically suffocating realm, flying from commitment, ever-ready with an evasive, self-rationalizing “loophole.” Such a life is “non-incarnated” (Act 43).

In contrast, when a person signs for her actions and situation, she becomes “visible,” to use a helpful word that recurs in Rowan Williams’s brilliant study (Dostoevsky 117, 119, 130).102 Persons are unavoidably communal: when a person acts, it’s likely that others will see the act and perhaps be affected by it. For the moment the viewer will “finalize” the person in the light of that act. But such “finalizing” can be liberating. In another early work, Bakhtin celebrated the boundaries that the viewer offers to the acting person. Such boundaries lend a person the form of “rhythm.” As Bakhtin writes, “the unfreedom, the necessity of a life shaped by rhythm is not a cruel necessity, . . . rather, it is a necessity bestowed as a gift, bestowed with love: it is a beautiful necessity” (Author 119). For Sartre (and some contemporary theorists), “the look” the other casts upon me objectifies me, pins me down: thus “hell is other people.” For Bakhtin, the other’s apprehension of my personhood comes as a gift around which my sense of self takes form. Bakhtin is a personalist.103 He recognizes that a person flourishes to the extent that he “signs” for his circumstances and deeds, and accepts the “rhythm” bestowed by others. In his Dostoevsky book, Bakhtin does not employ the specific terms he employed in his earlier philosophical work. But these terms are helpful in observing the ways in which Dostoevsky’s characters resist applying their “signature” or accepting the “rhythm” bestowed by others: the Underground Man in Notes, Raskolnikov until the end of Crime and Punishment, Prince Myshkin in The Idiot, Stavrogin in Demons. Recuperating these earlier terms serves a heuristic purpose by illuminating Dostoevsky’s own personalist vision.

For Dostoevsky’s robust realism points to the possibility of fully realized personhood. Recent studies seek to recover the concept of “person,” and recognize the word’s roots in the Christian tradition. “Person” stands in stark contrast to modernity’s model of the autonomous, voluntaristic subject.104 Philip A. Rolnick analyzes the ways a robust understanding of personhood has been dissolved in the acids of modernity, specifically in neo-Darwinian naturalism and the deconstructive denial of logos and transcendence. Rolnick recovers the patristic conception of the person as it developed in the early church’s understanding of the Trinity, and the outpouring of trinitarian love in Christ’s incarnation. Later, Thomas Aquinas roots his integration of reason and will in these trinitarian and christological sources. Created in the Trinity’s image and likeness, each person is particular—she is unique, differentiated, irreplaceable. But, in her personhood, she is like all other persons in being rationally, lovingly oriented toward both God and neighbor.

For Dostoevsky, to assert solitary, autonomous subjectivity is to refuse personhood as a given, inherently interpersonal reality.105 Like fellow personalist Jacques Maritain, both Dostoevsky and Bakhtin envision the givenness of an embodied person who “tends by nature to communion” (Person 47; emphasis added). By nature, the person is teleologically oriented toward both the common good and communion with God. Thus Bakhtin’s description of Dostoevsky’s ontology: “To be means to communicate.” A person is “nonself-sufficient”: “To be means to be for another, and through the other, for oneself. A person has no internal sovereign territory, he is always and wholly on the boundary; looking inside himself, he looks into the eyes of another or with the eyes of another” (“Reworking” 287). For Bakhtin, the words one speaks are necessarily shared, infused not only with the speaker’s sense of his listener but by the chorus of speakers he’s heard throughout his life. Persons change. And yet an essential, created “true self” remains real. When confessional dialogues succeed, they manifest what Bakhtin calls an encounter of the “deepest I with another and others” and reveal “the pure I from within oneself” (“Reworking” 294; emphasis added).

What is this “deepest I” or “true self”? I read Bakhtin here as elliptically signaling106 Dostoevsky’s Christian belief that a person remains grounded in the loving being of her Creator. Her “deepest I” reflects the divine image. Her pilgrim hope is to recover her divine likeness.107 The deep, “pure I” that Bakhtin discerns in Dostoevsky is not a Platonic form, divorced from material and social realities. It is not Descartes’s “I am” asserted through solitary introspection. Rather, the “deepest I” signifies a person who accepts his ordinary life among others, both receptive and available to others, and who sustains a “good taste of self” and a “realistic imagination” (Lynch, Faith 133), capable of “spiritually relevant [and] morally productive communicative efforts” (Wyman 4). Such a person accepts the twin realities of freedom and necessity, and the “third,” the ever-present reality of grace. Lynch writes that “some good taste of the self, as it is now, no matter how small the taste . . . will help bridge the gap between the actual and the promise” (Faith 130; emphasis added). The deepest, truest self is a graced gift, both actual and promised.

The Brothers Karamazov suggests that the patristic and monastic traditions offer indispensable practices that abet the recovery of one’s “deepest I” or “true self.” The novel’s narrator describes the monastic means of “self abnegation” in order “to attain the end of perfect freedom.” The narrator specifies that end: to find “their true selves” (30). Here too the work of Thomas Merton, well-known twentieth-century Cistercian monk (and lover of The Brothers Karamazov), can be illuminating—especially in an understanding of the novel’s description of Alyosha as “a monk in the world” (247). Merton wrote for countless readers outside the monastery, and understood that the “true self” could be discovered only in a person’s dying and rising and life in Christ. The person thus recovers the likeness into which he was created. Like Zosima—who, he admitted to Dorothy Day, “can always make me weep” (Ground 138)—Merton also believed that all are called to such self-abnegation, to be “monks in the world,” “contemplatives in action.” As he writes in Contemplative Prayer, “the Zosima type of monasticism can well flourish. . . even in the midst of the world” (28). Merton’s description of the “true self,” “the ascetic and contemplative recovery of the lost likeness,” entails small spiritual victories that any person may seek in the goal of “overcoming of conflict, anxiety, ambivalence, compulsiveness and the radical, repressed psychological claim that every individual harbors to a kind of omnipotence, a tendency to absolutize oneself” (Carr 52).108 I read the phrase that Bakhtin uses—“deepest I”—as congruent with Merton’s conception of the “true self,” and with “the person in the person”109 that Dostoevsky sought to portray in his novels. The “deepest I” is recovered through the grace of the Godman, Christ, not in pursuit of “mangodhood.” It is rooted in the kenotic Christ and participates in the self-giving life of the Trinity. Incarnational realism is grounded in and directed toward this embodied ideal: “the ideal,” as Father Paissy puts it, “given by Christ of old” (152), revealed in “the precious image of Christ” (276), whose face is mediated by icons like that from Sinai.110 The saint reflects Christ’s image and descends into the prosaic particulars of responsibility with a pilgrim hope of eventual ascent and homecoming. The scriptural saints—Abraham, Moses, Isaiah, Mary—hear God’s call and answer “Here I am.” Each responds not with an assertion of autonomous, imperial subjectivity (Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am”) but with an acceptance of finite, particular circumstances—“Here”—and a willingness to conform to the infinite Divine—the God whose name is “I am” (Exod 3:14), who became flesh and dwelt among us. The saint’s “hineni,” “Here I am,” bespeaks the “deepest I,” the “true self.”

“On earth” (276) persons remain pilgrims—viator, “on the way.” Fully recovering the “lost likeness” and “deepest I” transpires on a farther shore. But “bound for beatitude,” persons are here granted analogies of “paradise” (259) in the “good taste of self” experienced in relationship with others and the Other, in the “joy” for which Mitya rightly claims we are compelled to give thanks (499–500). When a person’s self-respect is secure,111 the gazes and words he shares with others need not deteriorate into the “vicious circle” of “sideward glances” and self-justifying “loopholes” so often represented in Dostoevskian dialogue. He can speak without “cring[ing] anticipation” of the other’s judgment (Problems 196). Lacking such security, a person seeks validation in the eyes of others, and can do so in excruciatingly self-defeating ways. Fearing the judgment he imagines in the other’s eyes, he hates both himself for seeking it and the other for imposing it. The will of the “true self” is sufficiently grounded in a rational intellect and creaturely confidence in the love of his Creator, in whose image he is made. In contrast, the false-self reacts to the other person absurdly. He asserts his will perversely and hurts both himself and others. Like no previous or subsequent novelist, Dostoevsky depicted these capricious assertions of will, and exposes their compulsivity and falsity.

But, especially in his final novel, he also depicted the recovery of “the deepest I,” the “true self.” Dostoevsky believed that “the person in the person,” in all his or her particularity, shares with “all” a common grounding in God’s oceanic love. Zosima observes that “all is like an ocean” (299); sharing in common creatureliness, each person is sustained by the overflowing of trinitarian love, and called to participate in that love.

Confessional Dialogue and Kenotic Attentiveness

Given the reality of sin, a “good taste of self” can be difficult to achieve and sustain in ordinary life. Dostoevsky portrays characters who fail, and who experience the guilt and shame that separate them from others through projection, fear, and egotism. The novice reader of Dostoevsky can be baffled by the absurd contortions into which these characters disfigure themselves.112 Confession offers an exit, but it “cuts both ways” and is a “two-edged sword” (31).113 Dostoevsky sees the pathological turn confessional dialogue can take. But he also recognizes confession’s crucial role in recovering health, the root meaning of “salvation” (Ford 1). He portrays the possibility of interpersonal—or intercreatural114—relations marked by enlivening mutuality.

Salvific confessions evince incarnational realism in their integration of openness and closure. The confessant experiences openness by exercising freedom, both in choosing to confess and in the way that he confesses. He articulates his fault without the pressure of inquisitorial coercion. He reveals himself with a clear sense of both his limits and potential. He can acknowledge and thus quell the anxiety that may arise in the “visualization of the self from the eyes of another” (Bakhtin, “Reworking” 294). If the other seems to be looking at him with judgment—and the good confessor strives not to—the confessant need not internally conform to that judgment. For example: imagine that I’ve done something cruel, confessed it to you, and then catch your eyes looking into mine. I think, “You’re looking at me as if I were really cruel. I guess it must be true: I’m nothing but a cruel person.” Apart from the projection that may be distorting my apprehension of the confessor, such a conclusion would be false in its univocal closure, its too-easy submission to the “form” imposed in your attention to me. As Morson and Emerson note: “I can be enriched by the other’s ‘rhythmicizing’ of me because I know that a particular image of me does not define me completely. But I can only be impoverished if I try to live as if another could rhythmicize me completely; such an attempt would be another path to pretendership” (Prosaics 194)—that is, a flight from responsibility. I remain responsible for my cruel deed, but it doesn’t utterly define me. To say that it does so is to utter “a false ultimate word” (“Reworking” 294).115

Another way of finalizing oneself, and ruining a confession, is by wearing a mask formed by “visualiz[ing] the self from the eyes of another” (294). The mask-wearer knows that his personhood can’t be reduced to a single characteristic. But the mask proves hard to remove when he habitually wears it and plays the role others expect. The family’s patriarch, Fyodor Pavolovich, exemplifies this habit. Even in Zosima’s cell, Fyodor relishes center stage, playing the role of buffoon, and then “confessing” it to all. When Zosima “pierce[s]” Fyodor with his insight into the old man’s motivation—“above all, do not be so ashamed of yourself, for that is the root of it all” (43)—Fyodor responds with a rare moment of truthfulness: “I always feel when I meet people that I am lower than all, and that they all take me for a buffoon. So I say, ‘Let me really play the buffoon. I am not afraid of your opinion, for you are every one of you worse than I am’” (43).116 Fyodor is smart—but he’s also lazy and stubborn. He refuses to humbly resolve, “I’ve been a buffoon. I’ll stop.” He immediately reverts to his “deceitful posturing” (43) and, later, bursts into the Father Superior’s dinner, smashes the mask to his face in wild revenge: “His eyes gleamed, and his lips even quivered. ‘Well, since I have begun, I may as well go on,’ he decided suddenly. His predominant sensation at that moment might be expressed in the following words, ‘Well there is no rehabilitating myself now, so I’ll spit all over them shamelessly. “I’m not ashamed of you,” I’ll show them and that’s that!’” (79). Ivan differs from his father in many ways, but Smerdyakov cannily observes that in his shame, Ivan is “more like [Fyodor] than any of his children” (531). In court, Ivan will publicly confess—but then, in a defensive posture born of shame, falsely and publicly affix to himself the mask of full-fledged “murderer” (as we’ll see in Chapter 6). Old habits are hard to break; new ones kick in only after arduous work. Fyodor has worn a mask for years; sustaining an honest confession may be beyond his capacity.117 But with Ivan, as we’ll see, there’s hope.

In confessing, one must also accept closure by taking responsibility. Imagine a man confessing to his wife without evasion, using the active voice, “Two weeks ago I lied to you. I take responsibility for that lie, and I’m sorry.” The husband enacts two “signings”: the first for the lie he told, and the second for the present confessional utterance. In this sense confessional utterance is “performative”: the words do something by enacting a person’s taking public responsibility for a particular deed.118 Consider Raskolnikov’s public confession in Crime and Punishment: his words comprise an efficacious deed. They restore—or begin to restore—a communal bond his murders had severed.119

A true confession rejects “loopholes.” But like so much else in The Brothers Karamazov, loopholes can “cut both ways.” On the positive side, there’s a loophole of personal growth, that which enables me to exercise my unfinalizability. If I’ve been a coward in the past, and others justly see me as a coward, I need not act cowardly now. “Forgetting” the way others view me, I can utilize the “loophole” of my freedom to act bravely and thus grow in a new and healthy direction.120 But if I employ a loophole in order to evade responsibility, it corrodes my confession. Perceiving what I take to be judgment, I strain to pull off the mask of “coward.” I begin my confession accurately: “I deserted my comrades in battle.” The trouble starts when I catch your gaze from the corner of my own, and interpret it—accurately or not—as labelling me as a “coward,” branding my very being. I feel shame and react. What began as a genuine attempt to sign for my failing deteriorates into a power struggle—my insistence upon personal unfinalizability versus your finalization. With a firmer sense of personhood and a better “taste of self,” I wouldn’t be so sensitive. Bereft of it, I grab a loophole: “I saw others running away. Some of them needed my help.” Squirming to retain my unfinalizability—“I’m not really a coward!”—I deny the freedom I exercised when I chose to run. I erase my “signature” and lose the opportunity to bring closure to one part of my life. The more habitually I grab a loophole, the less free I become.

Dostoevsky depicts numerous such fractured confessions in his work. Although he offers no sustained analysis of The Brothers Karamazov, Bakhtin’s close analysis of the narrator’s confession from Notes from Underground offers a heuristic that can be applied to his final novel. Bakhtin observes that “from the very first the hero’s speech has already begun to cringe and break under the influence of the anticipated words of another . . .” (Problems 228). He thus flees reality. He begins with a self-description, a pause, and a second self-description: “I am a sick man . . . I am a spiteful man.” His first utterance is accurate: “I am a sick man.” But in his pause, the reader can imagine the Underground Man casting a “sideward glance” at his listener, anticipating her forming an evaluation (“poor man, he needs help”). The Underground Man does seek pity from his listener. But simultaneously he hates his listener (to whom he has now become “visible”) for the privileged position from which she offers her sympathy. He recoils, and tries to destroy his need for her by insisting that he alone can speak any final word about himself: “I am a spiteful man.” But this is a “false ultimate word” for again the Underground Man looks at his listener, and cringes in anticipation: what if she should agree, and respond, “Yes, you really are spiteful.” The Underground Man has his “noble loophole” (67) at hand as he asserts his capacity for his “lofty and beautiful dreams” (65).

The Underground Man refuses to simply acknowledge his deeds and resolve to change. He could say: “I’ve been spiteful in the past, but would like not to be in the future.” “[S]uch a soberly prosaic definition [of himself] would presuppose a word without a sideward glance, a word without a loophole . . .” (Problems 232). By refusing to admit his ordinary human imperfection, the Underground Man refuses to live healthily with others. Perversely, he asserts his freedom by ranting that only he himself can have the final word about himself, even as he compulsively glares at the other from the corner of his eye. He is “caught up in the vicious circle of self-consciousness with a sideward glance . . . obtrusively peering into the other’s eyes and demanding from the other a sincere refutation. . . . The loophole makes the hero ambiguous and elusive even for himself. In order to break through to his self the hero must travel a very long road” (Problems 234; emphasis added). The “very long road” to his “true self”—his “deepest I”—requires humility, the virtue that grounds love. Liza offers him love, and he rejects her cruelly. Willfully, he persists in scrawling his notes, which an outside editor cuts off arbitrarily.121

Other characters in Dostoevsky’s fiction employ confession as a meretricious means toward self-justification, punishment, aggrandizement, or exhibition. Robin Feuer Miller analyzes these and uncovers Dostoevsky’s implicit critique of Rousseau, whose Confessions stands in stark contrast to St. Augustine’s: “In Dostoevsky’s canon . . . the literary—bookish—written confession most often tends to be, to seem self-justification, or to aim at shocking the audience. But Dostoevsky does concede that the choice of an audience is important, and successful, genuine confessions do occur—witness Raskolnikov with Sonya, or ‘the mysterious visitor’ with the elder Zosima” (“Rousseau” 98). Julian Connolly highlights Dostoevsky’s “characteristically multifaceted way [of showing] both the shining potential of an effective confession and the frustration and suffering that result from a perversion of the confessional impulse” (“Confession” 28). Fellow novelist J. M. Coetzee concludes that “Dostoevsky explores the impasses of secular confession, pointing finally to the sacrament of confession as the only road to self-truth” (230).

But Dostoevsky never depicts the actual sacrament of confession. In fact, Father Zosima is actually accused by “opponents” of “arbitrarily and frivolously degrad[ing]” the sacrament of confession by attending to the many who come to the monastery “to confess their doubts, their sins, and their sufferings, and [to] ask for counsel and admonition” (31), apart from the sacrament’s traditional form. Nevertheless, Zosima’s encounters with his visitors are portrayed as sacramental. They are penetrated by divine grace. Zosima and Alyosha help their confessants to step out of their vicious circles, to humbly accept their “visibility” before others, and to speak with clarity and resolve. To each, they bring a Christ-like authority.

Their authority lies both in their faith and in their profound capacity to be attentive to others. In stressing the “penetrative” quality of their authoritative words, Bakhtin draws from Ivanov’s Freedom and the Tragic Life, which emphasizes “proniknovenie, which properly means ‘intuitive seeing through’ or ‘spiritual penetration’ . . . . It is a transcension of the subject. In this state of mind we recognize the Ego not as our object, but as another subject. . . . The spiritual penetration finds its expression in the unconditional acceptance with our full will and thought of the other-existence—in ‘thou art’” (26–27). The confessor’s attentiveness allows him to discern the “pure I from within” the confessant; his authoritative discourse penetrates and is received by the confessant as “internally persuasive” (Discourse 342).

Deep attention requires the relinquishment of distraction and self-absorption. In her seminal essay on “School Studies,” Simone Weil stresses the kenotic dimension of attentiveness: “The soul empties itself of all its own contents in order to receive into itself the being it is looking at, just as he is, in all his truth. Only he who is capable of attention can do this” (115; emphasis added). Ivanov also employs the Greek word kenosis: “If this acceptance of the other existence is complete; if, with and in this acceptance, the whole substance of my own existence is rendered null and void (exinanito, κένωσις) then the other existence ceases to be an alien ‘Thou’; instead, the ‘Thou’ becomes another description of my Ego” (27). But as Bakhtin would insist, and as Alina Wyman extensively demonstrates, kenotic, Christ-like love or “active empathy” does not entail self-obliteration: “Incarnation is seen as a model of an active existential approach to one’s neighbor” (Wyman 6).

The concept of kenosis is, of course, central to the theological understanding of Christ’s incarnation, and is especially pronounced in the Russian Orthodox tradition.122 The locus classicus is the letter to the Philippians in which Paul commends Christ’s “self-emptying” as exemplary:

Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus,

who, though he was in the form of God,did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited,but emptied himself,taking the form of a slave,being born in human likeness. And being found in human form,he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death—even death on a cross.

Therefore God also highly exalted him and gave him the name that is above every name,so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father. (Phil 2: 5–11)123

In The Russian Religious Mind, George P. Fedotov stresses the importance of kenotic spirituality in Russian Orthodoxy and traces its roots to two eleventh-century sources: first, to the cult surrounding the politically motivated murder of the Princes Boris and Gleb, who treated their murderers with humility and “forgiving nonresistance” (101), and so were canonized as saints; second, to the life of Saint Theodosius, who was born rich but willingly wore poor clothes and worked in the fields with slaves. As a monk, he opened up relations between the monastery and the lay world; he began the long tradition (of which Zosima is exemplary) of monks serving as confessors for lay people.124 Dostoevsky wrote, “‘In childhood I heard these narratives myself, before I even learned to read.’ These stories of the lives of the saints were no doubt steeped in the special spirit of Russian kenoticism—the glorification of passive, completely non-heroic and non-resisting suffering, the suffering of the despised and humiliated Christ—which is so remarkable a feature of the Russian religious tradition” (Frank, Seeds 48).

In their relinquishing of self, and willingness to enter into the suffering of others, Zosima and Alyosha reflect the “attitude that is also [theirs] in Christ Jesus.”125 Thus, they elicit the conversion of others, helping them move from willful assertion to willing receptivity. And thus the recurring resonance of the novel’s epigraph. Paradoxically the “deepest I” of the confessor who, through attention, “dies to himself” emerges as most fully himself and authentically authoritative. And for Christ’s kenosis the Father gives him “the name which is above all other names” (Phil 2:9). Analogously, Dostoevsky’s confessors emerge as truly authoritative by relinquishing the power others may project when they plead, “Decide for me!” The confessor never decides for the person struggling under the burden of conscience. Instead, without manipulation or coercion, he or she guides.

The novel’s counter-image to Christ, the Grand Inquisitor, does decide for others: “we shall allow them even sin” (225). As Roger Cox observes, the Inquisitor’s authority is actually tyranny, his miracle sorcery, his mystery mystification (Terras 235). The Inquisitor claims to love humanity but sees persons only as “impotent rebels” (222, 223), “pitiful children” (225), and “geese” (227). Zosima and Alyosha see persons, and help them to recover “a good taste of self.”

The authoritative words of Zosima and Alyosha reverberate with divine inspiration. In the phrase “penetrated word” Caryl Emerson aptly translates Bakhtin’s proniknovennoe slovo by suggesting its two dimensions: the word penetrates the one who hears it, but is itself “penetrated” and authored by the authority of God. It is thus “capable of actively and confidently interfering in the interior dialogue of the other person, helping the person to find his own voice” (“Tolstoy” 156). Bakhtin’s illustration is Prince Myshkin, who admonishes Nastasya after she taunts Rogozhin in Ganya’s crowded apartment, provoking melodrama and violence. She is wearing a mask, “desperately playing out the role of ‘fallen woman,’” and “Myshkin introduces an almost decisive tone into her interior monologue”:

“Aren’t you ashamed? Surely you are not what you are pretending to be now? It isn’t possible!” cried Myshkin suddenly with deep and heartfelt reproach.

Nastasya Filippovna was surprised, and smiled, seeming to hide something under her smile. She looked at Ganya, rather confused, and walked out of the drawing-room. But before reaching the entry, she turned sharply, went quickly up to Nina Alexandrovna, took her hand and raised it to her lips.

“I really am not like this, he is right,” she said in a rapid eager whisper, flushing hotly; and turning around, she walked out so quickly that no one had time to realise what she had come back for. (The Idiot, Part One, ch. 10, cited in Problems 242)

For a moment Nastasya speaks clearly and resolutely, without a mask; she seems “to find her own voice.”126 But in the events that follow, Myshkin flies from the finitude of decision. He responds to others, especially Nastasya, with a kind of boundless pity and reveals a “deep and fundamental horror at speaking a decisive and ultimate word about another person” (Problems 242). In fact, in the scene cited above, his words are “almost decisive” in displaying both an appreciation of Nastasya’s potential—“surely you are not what you are pretending to be now”—along with a judgment of actions for which she ought to take responsibility: “Aren’t you ashamed?” he cries “with deep and heartfelt reproach” (242). But Myshkin grows increasingly indecisive, and his affect upon others proves violent and tragic. By the novel’s end, he emerges as a Christ-manqué.

By contrast, Zosima and Alyosha do speak decisively and image Christ. Deeply attentive, they reject the univocal pity “which wipes out the need and the agony of all partial and analogical choices of the good” (Lynch, Christ and Apollo 172). Their utterances—sometimes “spoken” in the forms of bow, blessing, or kiss—accrue beyond their initially penetrative effect. They serve as healing presences for those tempted toward destruction and help them to sustain integral personhood.

With this conceptually laden prelude behind us, we turn to a close examination of the persons whom Dostoevsky creates—Zosima and Alyosha—and the persons to whom they lovingly attend.