Читать книгу The Adoption Machine - Paul Jude Redmond - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

In August 2011, I visited my birthplace, Castlepollard Mother and Baby Home, in the company of six other people adopted from there. We had met on Facebook and another lady and I had organised the visit. Years later we realised that we were the first known group of adoptees to return to their old home as a group.

My childhood fantasy was of an old Georgian house with my young mother in an oversized chair that was covered with warm, colourful throws, by a window where golden sunshine streamed in as I lay swaddled in her arms. Gentle nuns fluttered around, cooing and happy.

The reality in 2011 was a cold, grey, ugly institution. Empty rooms and peeling paint. Our group visited the Angels’ Plot and stood on the narrow strip where unknown hundreds of babies and children had been buried just a few feet below where we walked around. We planted a tree in their memory.

That forgotten plot affected me deeply. It was life-changing. I left as a survivor determined to do ‘something’. In the days and finally years that followed, I hunted down every scrap of information I could find about Castlepollard and particularly the Angels’ Plot, and then I broadened my attention to the other Mother and Baby Homes in Ireland. More Angels’ Plots. More horrors. I became an activist by default. The ‘something’ I wanted to do, I realised afterwards, included never letting people forget. I wanted to ram hard facts and figures down Ireland’s throat.

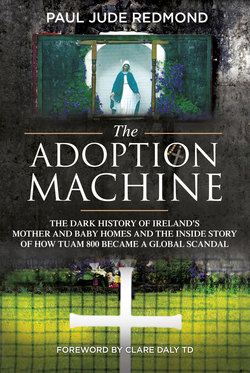

I published all my research, nearly 100,000 words, across the various adoption groups. I did a little unpaid citizen journalism about the Homes and our campaign for truth and justice. Over the years, my family, friends and fellow activists increasingly nagged me to write a book and tell the story properly, and I finally cracked and agreed to do it in early 2017. I took four months off work over the summer and simply sat down and wrote. And I couldn’t stop. The book grew to twice its intended size before I was finished, and I still feel it is not enough.

Approximately 100,000 girls and women lost their babies to forced separation since independence in 1922. Church and State considered the illegitimate babies as barely human. At least 6,000 babies died in the nine Mother and Baby Homes where some 35,000 girls as young as 12, and women as old as 44, spent years of their lives, and almost no one cared. Even now, mothers and babies still cry out for remembrance and justice. Their cries from beyond the grave are ignored by Irish society, just as the cries of their short poignant lives were ignored in the Homes.

The Adoption Machine is not just a book. It is also an activist tactic and part of our ongoing campaign to ensure that the last, dirty secret of Holy Catholic Ireland is finally dragged into the light. It is a rage against the machine. A voice in the wilderness. A memorial to my fallen crib mates.

And, as I write from the deepest part of my heart, I still hear the voices of the angels crying for justice. And remembrance. And love.

There are many villains in this story. There are a handful of heroes too. These heroes are all too human; flawed, stubborn products of their time. Yet they all share one feature: they had good hearts. Whether they succeeded or failed is not important, they tried their best. They too should be remembered: Aneenee FitzGerald-Kenney, Alice Litster, Dr James Deeny, June Goulding, among others.

This story begins with such a hero, Captain Thomas Coram ...