Читать книгу Sustainable Luxury - Paul McGillick Ph.D - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

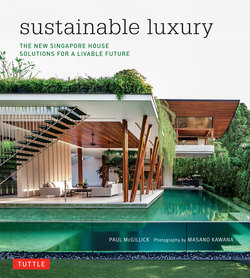

ОглавлениеSUSTAINABLE LUXURY: IS IT A CONTRADICTION IN TERMS?

This book presents some of the very best and most luxurious new homes in Singapore. Each of them, in one way or another, represents a response to the challenges of creating luxurious yet sustainable homes in one of the world’s most expensive cities—and in a sweltering tropical climate!

You may assume that luxury is inherently self-indulgent and, therefore, non-sustainable. But is it? The architects of these homes, together with their clients, demonstrate that this is emphatically not the case. This book reveals the many innovative solutions they found in doing so, illustrating in the process how Singapore has become an incubator of innovative residential design.

Crucially, each home achieves its own special kind of luxury through the creativity and imagination of its designers working in close collaboration with their clients. As architect Mark Wee, puts it, ‘Designing a house for a client is, for them, a highly emotional thing … it is not just money invested, it is meant to be a setting for them to live for a long time.’ In fact, with most of the homes in this book, the marriage of luxury and sustainability has been achieved not by spending huge sums of money but by the application of some simple, imaginative and well thought out strategies.

Most of these homes are free-standing landed properties. In the tiny island state of Singapore, this means, by definition, that a lot of money is spent to acquire the land even before the design process begins. Money, though, is forever the elephant in the architectural room. Despite the many lessons learned from traditional architecture about how to live in a tropical climate, money has always provided the resource—as everywhere else in the world— that has enabled architecture to experiment, explore and innovate. Over time, the lessons learned from these ‘luxurious’ projects are applied across the board, including to medium- and low-cost housing.

Rather than viewing luxury and sustainability as being mutually exclusive, it may actually be that true innovation is driven by the desire for luxury, especially given that luxury and comfort mean such different things to different people. Let me give just one example of how a current trend in Singapore is bringing together the issues of luxury, sustainability, innovative design and financial capacity. This is the way in which architects are currently experimenting with multi-generational houses. They are responding to the desire to maintain the extended family, to the high cost of real estate (that encourages adult children to remain at home longer) and to changing social mores which result in people, especially the younger generation, seeking greater independence and privacy. In other words, how do we reconcile privacy and community within the contemporary family home? The result is some very beautiful houses, but houses that are also highly sustainable—socially, culturally, economically and environmentally.

Sustainability: The Big Picture

‘Sustainability’ has become a somewhat rubbery term, so let us put things into perspective. There is a lot more to sustainability than simply throwing out the air-conditioner. Showing me over his Travertine Dream House (page 142), architect Robin Tan Chai Chong made himself very clear: ‘We don’t buy into the trendy new way of describing green architecture. We look at it in a holistic manner…. What are our limitations in Singapore? We don’t produce anything. We import everything. The task of architecture is to balance consumption.’

In this case, the client had worked his way up through a series of modest dwellings to this, his dream house. He wanted all marble finishes. Tan suggested travertine, just as beautiful but less expensive and less ostentatious. The client agreed and went off to Italy to source the travertine himself at a fraction of the cost. ‘That’, says Tan, ‘saved resources. Saving money is a kind of sustainability.’

The back story to this house is reflected in different ways in all the other homes in this book. Yes, there is money to play with and, yes, these homes are luxurious. But each home is luxurious in a way that is right for the people living in it, and each represents a thoughtful and innovative approach to the challenge of sustainability.

The true splendour of the Andrew Road House by A D Lab (page 54) lies below ground level where there is a lush, cool water garden court.

The Mandai Courtyard House (page 34), with its modestly scaled living/dining space and engawa deck, is the epitome of the ‘good neighbour’.

Just as important is the way the architects and their clients have viewed environmental sustainability as part of a bigger picture. The result is that residential architecture in Singapore is setting new benchmarks, not just in the tropics but throughout the world.

In my previous book, The Sustainable Asian House (2013), the word ‘sustainable’ was used in the broadest sense, and a number of readers commented that they appreciated the fact that I was not just looking at sustainability in a narrow environmental sense. In this book, I want to be clear from the outset how I define the term since it is often used too loosely and ends up being applied to things that are not even remotely sustainable.

The term ‘greenwashing’ is sometimes used to describe this sleight of hand, applied to design which only pretends to be environmentally responsible. Nonetheless, one can argue that a mixture of legislation and good intentions has resulted in an architectural agenda that is now broadly, and genuinely, sustainable. As Robin Tan also points out: ‘Architects have always been environmentally sensitive, socially sensitive… but we look at it in a holistic way. There needs to be a holistic view of sustainability.’

Today, sustainability looks less like a single aspect of design, for example, using specifically sustainable materials, and more like a systemic challenge that involves looking at how all the elements fit together as a whole. It may not be simply a case of using particular materials to conserve energy or reduce carbon emissions but more about examining the big picture. It is not so much the particular materials that are used but what is done with them!

There is much more to sustainability than the materials used and whether a house uses too much air-conditioning. It involves the entire habitus of the society, the aggregate of all the things that enable a community to sustain itself physically, socially and culturally over the longer term. It is what makes the community unique and encompasses the physical environment (including climate), the language, the cultural heritage and the memories of people, without which there would be no culture, language or competence in the performance of everyday tasks.

It is this broader context that frames this book. Sustainability consultants Leyla Acaroglu and Liam Fennessy have commented that ‘Sustainability is the equity of social, economic and environmental resources.’1 In other words, a sensible balance of these three core factors creates an ecology in which all the participating elements influence one another and work together to achieve a common end. As Acaroglu says elsewhere: ‘When you step back from the hype, sustainability is really about understanding and working with systems.’2

When I talk about sustainable living in the Singapore context, I am referring to a broad range of environmental, social, cultural and economic issues that are currently shaping this vibrant island nation as it approaches the fiftieth anniversary of its founding as a nation state, and specifically the way in which its residential architecture is responding to these issues. As architect Mark Wee says, ‘Singapore may still be less than fifty years old but there is a fair degree of nostalgia… the task of the architect in Singapore is to create new spaces that can add to the soul of the city.’

Architecture is not produced in a vacuum. It responds to the programmatic requirements of its clients, to the specifics of location and to regulatory constraints, which in turn reflect established societal goals and values. This makes up what the great anthropologist of the South Pacific, Bronisław Malinowski, referred to as the immediate context, the actual situation we find ourselves in. Beyond that, however, is what he terms the wider context, or the broadly cultural context which shapes our responses. Meaning, he said, was function in context, what we are doing at any given moment within the broader context.

While it may not be always apparent amongst the swirl of professional obligations, shopping lists, domestic chores and getting the kids to school on time, meaning is what drives our lives. Take meaning out of someone’s life and the result is alienation: psychological breakdown, anti-social behaviour and aimlessness. Our lives become unsustainable.

The primary factor in sustaining ourselves is the home; in other words, a house (or shelter) imbued with meaning. The home services Abraham Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs: physiological, safety, love and belonging, esteem and self-actualization. These needs have to be met if we are to sustain ourselves physically, personally and spiritually.

While we exist as individuals, we are also members of successively larger human clusters, from one-on-one relationships, families and social groups to entire nations. We cannot separate ourselves from the larger picture. Therefore, sustainability is about how we share this planet with everyone and everything else over the long term. Every dwelling has its own responsibility to contribute to the long-term sustainability of the planet so that this and subsequent generations of human beings can live effective and fulfilling lives.

The idea behind the Barnstorm House (page 150) is the image of a large-scale barn made from traditional materials and tailored for outdoor tropical living.

This book explores how the contemporary Singaporean home sustains its occupants physiologically while also contributing to the wider agenda, looking at a number of approaches to emotional, familial and cultural sustainability.

This is the immediate context. The wider context is Singapore itself. The island state can be viewed as an ongoing experiment in sustainability. Since deciding to go it alone in 1965, the key driver has been how to sustain itself economically given that its only resource is its people. This has required constant adaptation, largely in response to global economic change. However, other issues have emerged over time, in particular the question of how the island state sustains its people across all those other needs—housing them and providing for their non-material needs in order to sustain a stable and socially healthy community.

Sustainable Luxury looks at how recent changes have impacted on and been reflected in residential architecture: economic changes, the emergence of new professional categories and new kinds of clients with new kinds of expectations and lifestyles, the impact of housing affordability, and new approaches to traditional multi-generational living and changing family patterns (smaller families, singles and childless couples). Added to this is a growing sense of the nation’s own history and how it connects with the history and cultures of its neighbours and with a long tradition of coping with a tropical climate.

Sustainability: The Singapore Context

After a period of gradual evolution towards full self-government, the Federation of Malaysia was inaugurated on 9 July 1963, incorporating Malaya, Singapore, Sabah, Sarawak and Brunei. The life of this new country was, however, short-lived and Singapore separated from the Federation to become the independent Republic of Singapore on 9 August 1965.

Driving this separation was the issue of ethnic inequality. Article 153 of the Malaysian Constitution legislated affirmative action in favour of the ethnic Malays. Singapore’s Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, argued this was intolerably discriminatory towards other ethnic groups and reluctantly concluded that there was no alternative but for the countries to go their separate ways.

This non-negotiable principle has been crucial to the development of Singapore. It was, of course, a moral issue. But we need to remember that for Confucians the moral and the ethical are inseparable.3 As a result, there is always a powerful pragmatic corollary at work, namely, that what is right is also what ultimately benefits us.

What was ‘right’ was the principle of an inclusive multi-culturalism—a genuine pluralism—and an acceptance of the benefits of cultural diversity. Inclusiveness and diversity bring many benefits, including an openness to new ideas and an awareness of different ways of doing things and alternative ways of seeing things and resolving problems. In turn, this leads to a resilient and innovative economy and to a society with the texture that makes it worth living in. In other words, social equity or ‘equal opportunity in a safe and healthy environment’. Social equity has long been regarded as an aspect of sustainable development, which itself comprises three key elements: economic, political and cultural sustainability. While social equity may be seen as morally desirable, even to be a universal human right, the notable thing about Singapore is that from the beginning it was seen as a driver of prosperity.

Singapore regards social equity as a matrix of collective and individual responsibility rather than some kind of right. The Singaporean government is nothing if not pragmatic. Individuals are encouraged to take responsibility for their own lives rather than look to the state. Hence, they are required to contribute to a ‘provident fund’ to ensure their own health care and retirement income. On the other hand, through the Housing Development Board (HDB), established in 1960, the government undertakes to provide affordable housing for all citizens. Flats constructed by the HDB are priced according to affordability rather than construction costs or resale pricing. Accordingly, the risks associated with development—rising land prices, construction and labour costs—are borne by the HDB, representing a substantial subsidy. Likewise, the government invests heavily in high quality universal education, with a strong emphasis on producing an adaptable workforce geared to innovation.

Such measures, along with a progressive taxation system, have seen per capita income grow more than ten times since independence. Even allowing for growing income inequality and falling housing affordability, the achievement has been significant, making the country the most affluent in the region.

Architect Guz Wilkinson is known for his gorgeously luxuriant houses, such as The Coral House (page 86), which merge seamlessly with verdant tropical gardens and water features.

Even more significant is the fact that Singapore is also highly adaptive, which is another way of saying it has sustained itself very successfully during an era of rapid change in the global economy. The global economy is arguably more important to Singapore than any other country because Singapore, apart from its strategic location and deep water port, has no natural resources. It follows that social equity is more than simply a lofty ideal. For Singapore, it is a necessity because social equity means optimal participation by everyone in the economy and in social affairs. Without genuine social equity, Singapore would be unsustainable.

Singapore is an island of 714.3 square kilometres. Its current population is 5.3 million, which means a spread of 13,700 people per square kilometre. The population is projected to reach 6 million by 2020 and 6.9 million by 2030. This prompted a controversial White Paper, released in 2013, significantly titled A Sustainable Population for a Dynamic Singapore.

Growing public disquiet about population growth, which has contributed to a housing affordability and availability crisis, has resulted in new restrictions on expatriate workers. These currently make up 44 per cent of the workforce and the previous ratio of one expatriate worker for every four native Singaporeans has been replaced by a ratio of 1 : 8. This has contributed to a labour crisis, especially in the construction sector where the shortage of labour is now becoming a major impediment to development. Like other affluent societies, service industries have become dependent on expatriate labour to do the jobs local people are no longer prepared to do.

In response to an overheated property market, the government has introduced a number of dampening measures, including restrictions on mortgages. At the same time, the HDB has increased its construction of public housing apartments, from 58,731 under construction in 2011 to 72,737 under construction in 2012. Notwithstanding this increase, there was actually a fall in completed flats, contributing to long waiting times and leading to overcrowding as extended families squeeze into apartments of inadequate size.

Nor is population growth an ‘urban myth’. It is very real and is widely regarded as contributing to recent problems as seemingly unrelated as more frequent train breakdowns and urban flooding.

Alongside housing affordability, the cost of living overall is becoming a major concern in Singapore. It is now the eighth most expensive city in the world and the third most expensive in Asia. Again, this can be seen as partly an imported problem. As one architect remarked to me while researching this book, ‘Singapore is the new Monaco—a place to park money.’ It is certainly a tax haven with a low tax rate on personal income among a number of factors— such as other tax measures, Singapore’s location, the fact that it is almost entirely corruption-free, the availability of a skilled workforce and advanced infrastructure—attracting large amounts of foreign money. It is estimated that one in every six Singaporean households have at least $1 million in disposable income. Despite growing disparities in income, real economic growth continues.

Formwerkz typically brings nature into the home, often with mature trees providing indoor greenery, such as in the Tree House (page 78).

Because it is so exposed to shifts in the global economy, Singapore has also experienced demographic changes related to economic change and the emergence of new professional groups. Its highly diversified economy is a result of deliberate government policy to ensure that Singapore remains sustainable. It is now, for example, the fourth most important financial centre in the world, the fourth largest foreign exchange trading centre in the world and the world’s largest logistics hub. With new professional groups, an ever increasing level of education and the emphasis on maximum connectivity with the rest of the world, Singapore’s lifestyle is becoming increasingly diverse. This diversity, along with the economic issues discussed above, is having a fascinating impact on the residential architecture of Singapore.

Almost paradoxically given the seeming ‘internationalization’ of Singapore, it has an emerging identity that many once felt it would never achieve. After a period of frantic and indiscriminate demolition and reconstruction, Singapore rediscovered its built heritage and, with it, a cultural heritage. Consequently, precincts such as Tiong Bahru, Joo Chiat, Chinatown, even the raffish Geylang, which managed to maintain their cultural continuity, have become sites for the kind of cultural memory that is essential to a nation’s identity. As Singapore approaches its fiftieth birthday, there is a growing sense of the island state’s uniqueness. Even the much satirized ‘Singlish’ is a marker of this. Singapore English consists of more than quaint inflections like ‘la’. It has its own emergent lexicon and phonology, making it a distinct form of English. Mixed in with the other indigenous languages, supported by the government’s four official languages policy, this makes Singapore unique linguistically.

The Travertine Dream House (page 142) has a rooftop garden, which cools the master bedroom below it.

From Tropicality to Sustainability

A language does not stay the same. It is constantly evolving. Words come to mean different things over time without necessarily losing their history, and words can mean different things in different parts of the world because different places have different histories. English, for example, is not a single language but a whole variety of languages which may look the same on the surface but which vary considerably lexically and phonologically.

I have already mentioned how Singapore English is a distinct variety that is gradually becoming even more distinct. I also suggested that this is a pointer to Singapore’s emerging identity. Far from being an ‘instant city’ or just a giant shopping mall, Singapore has a unique character that goes back much further than 1965.

Pursuing the linguistic model for the moment, Iet us imagine the contemporary Southeast Asian home as an intersection of past and present, a combination of Malinowski’s immediate and wider context.

In her pioneering study of traditional housing in Southeast Asia, The Living House: An Anthropology of Architecture in South-East Asia (1990; 2009), Roxana Waterson comments that ‘Architecture involves not just the provision of shelter from the elements, but the creation of a social and symbolic space—a space which both mirrors and moulds the worldview of its creators and inhabitants.’4

Here we have the intersection of two functions that make the home sustainable. On the one hand, the home is a shelter and a refuge from the world, a place where we eat, sleep and raise our families, where we sustain ourselves as physical entities. On the other hand, the home is a repository of all our values and beliefs, accumulated over generations, and so sustains us emotionally and spiritually.

Waterson’s book not only describes the physical forms of traditional housing in tropical Southeast Asia but also demonstrates the important role it has played socially and symbolically. Two points are worth highlighting. First, unlike Western houses where walls were important both as enclosures and as supports for the roof, the vast majority of traditional tropical houses consisted largely of a platform supported by piles and a dominant roof, with only token walls made from perishable natural materials like palm fronds.

Secondly, the house, typically occupied by a number of related families, combined habitation and ritual. Indeed, ritual often predominated, meaning that there was less of a need for separate places or buildings for worship or public functions.

Is it casting too long a bow to suggest that these original characteristics of the Southeast Asian home linger on in the homes of today as they increasingly aspire to respond to their place in a tropical climate and as part of a tradition of tropical living?

Take, for example, the strong connection between the inside and the outside, with terraces extending out from the interior spaces. Especially notable in this respect is the growing enthusiasm for open bathrooms, which is partly a sensual indulgence involving the pleasure of bathing in outdoor tropical luxury but partly a pragmatic anti-mould strategy for airing the wet areas of the house. There are numerous examples in this book, but no better example of deliberately revisiting vernacular tradition than Randy Chan Keng Chong’s ‘windowless’ house, the Jalan Mat Jambol House (page page 128), which is almost completely open and effectively raised off the ground as though on piles.

Today, however, the ‘sustainable Singapore house’ has moved on from the 1990s explorations in ‘contemporary vernacular’5 and the quest to reconcile modernist principles with cultural history and a tropical climate. While these preoccupations remain, they have taken on more sophistication. Today, it is more accurate to speak of place-making, that is to say, a mix of geographic, cultural and temporal place. Moreover, sustainability is seen as a broader and more complex imperative involving not just passive strategies for cooling (cross-ventilation, breezeways, shading, use of greenery and water, etc.) but other things, such as recycling (of materials, and of entire buildings to avoid demolition and rebuilding), minimizing waste and incorporating flexibility for future reconfiguration.

The award-winning Namly Drive House (40) has a water garden in the living room, which draws and cools air through the entire house.

Sustainability: A Broader Agenda

Singapore is not unique in fretting about whether it has an identity or not. But, like other countries that also fret, it is probably just a case of not having noticed up until now that it has had an identity all along. I began by reviewing the circumstances of Singapore’s birth and by noting the importance of cultural diversity and inclusiveness—surely at the heart of the Singaporean identity— along with its position as a key entrepôt. It has always been a melting pot and it is even more so today with such a large percentage of its population made up of expatriates and permanent residents. This demographic diversity is increasingly reflected in greater urban diversity and lifestyles.

There is also the ongoing issue of space or, rather, the lack of it. The government has responded to this with the vision of Singapore as a garden state where the public realm is effectively also the private realm, thus compensating for the lack of private space. This merging of the public and the private is one thing that gives Singapore its distinctiveness.

Nonetheless, there will always be a need to separate the private from the public domains. The traditional Asian emphasis on family and the collective is increasingly required to accommodate a new individuality, a demand for more private space. The ongoing issue is how to be together and yet separate, played out both in the domestic context and in the wider urban context. Domestically, it is reflected in the planning of the home and in the various strategies for dividing and linking space—gardens, courtyards and promenades. In the wider community, it is a case of developing a sustainable urbanism where Singapore, as an intensely urban society, can nonetheless service the non-material needs of its citizens.

The homes in this book have been chosen to illustrate the various ways in which residential architecture is responding to all these issues. A particularly interesting example is the way in which high-density and high-rise living is increasingly seen as an opportunity rather than a drawback. In high-rise apartment buildings, this is signalled by emphasizing and enhancing the panoramic views and by vertical connection with nature—green walls and green terraces—to generate a sense of being connected with nature even when living many storeys up in the air. Inside, there are initiatives (currently being driven by the HDB) to rethink the planning of apartments to more effectively accommodate the multi-generational family.

This also reflects a new sensitivity to the needs of clients, an acknowledgement of the need to make multi-residential living sustainable in the social, familial and personal sense. While the HDB is encouraging new apartment configurations to accommodate the extended family in public housing, at the other end of the property spectrum developers are building open-plan apartments—’semi-white plans’—to allow occupiers to customize their personal space. As with the idea of vertical landscapes, the aim is to replicate the feeling of living in a landed house with all the individuality that implies and a shift away from the standardization of traditional apartment design.

Waterson points out that ‘Inhabited spaces are never neutral; they are all cultural constructions of one kind or another.’6 In other words, they embody meaning. But an ongoing issue is the tension between architects and their clients as to who decides the ‘meaning’. There is always a tendency for architects to ‘over-design’ in order to control the ‘meanings’ embodied in the home. The problem with this is that the meanings are the architects’ meanings, not those of the people who will be living in the home. This is not a sustainable way to go about things. Happily, the houses in this book exemplify a trend towards a sustainable collaboration between architect and client.

It may seem an obvious thing to do, to design a house that is right for the occupants, but actually houses are very often designed to reflect only what the architect thinks is important. However, there is now a marked trend in Singapore to highly customize residential design. It is, as architect Alan Tay says (see the Sembawang Long Houses, page 70, and the Tree House, page 78), a matter of asking ‘how the client would use the house’ and this can involve a lot more than the basic programme, with its number of bedrooms, etc. Occupiers have an annoying habit of filling and decorating a house with their favourite things, which can often result in a contradiction between the way the house has been designed and the way it is used. An obvious way to avoid this mismatch is to work closely with the client from the beginning.

This is a powder room in the basement of The Coral House (page 86) that no one wants to leave because of its view of the sunken swimming pool).

Clients now often insist on being part of a collaborative process. This book has many examples of clients being actively involved. With the remarkable shophouse conversion by Mark Wee in Neil Road (page 26), the client had a clear vision of a sustainable marriage of heritage and the contemporary and made it clear, saying ‘I didn’t want a house, I wanted a home.’ In Chang Yong Ter’s award-winning Namly Drive House (40), the client wanted ‘two homes in one house’. The client at Guz Wilkinson’s The Coral House (page 86) comments, ‘I was born in Singapore. This is the tropics. And I don’t like being cooped up in an air-conditioned room. When we were looking for an architect, we were very mindful that we wanted someone who would blend with our taste and style, not someone because he has a name.’ At The Cranes in Joo Chiat (page 200), the client, whose day job is in shipping and whose boutique developments are almost a hobby, worked closely with the architect to devise a multi-residential model that catered for a new demographic of professionals, but nourished by the rich, local urban heritage.

Indeed, there are architectural practices, such as eco:id, who only work on residential projects that are truly collaborative and where there is a natural empathy between architect and client.

This is not just a matter of clients briefing their chosen architects. This is a whole new paradigm for the client–architect relationship, which involves an ongoing conversation between the two that is intense and highly personal. Sustainability—environmental, personal and cultural—is a key driver for all parties and it is an approach which is drawing attention from all over the world.

Sustaining a Changing Singapore

Sustainability is not an option for Singapore, it is an imperative. In environmental terms, this means conserving water, looking for ways of moderating dependence on air-conditioning, attempting to restrict the use of private motor vehicles and making the best use of the available land. This, in turn, has implications for the social sustainability of the country. Land shortage and the cost of land—as one architect, Chu Lik Ren, said to me, ‘Space is a universal constraint’—imply high-density, high-rise and smarter ways of using space. If the use of private motor vehicles is to be discouraged by ownership restrictions and financial imposts, then an affordable, convenient and efficient public transport system has to be provided. Moreover, such a system has to be attractive and comfortable if it is to compensate for the lack of a private car. In the same way, to maintain social harmony the emotional well-being of the community needs to be ensured by providing communal amenities to compensate for the constraints of apartment living.

Economically, the country needs to be infinitely adaptive, constantly sensitive to shifts in the global economy and alert to new opportunities. Hence, the government has placed great emphasis on education, aiming for a highly skilled, flexible and innovative workforce, significantly aiming to make Singapore the design hub of Asia and a centre of creativity.

The key to sustaining an adaptive economy is diversity and inclusiveness, and with more than one-third of the workforce of non-Singaporean origin, not to mention its natural ethnic mix, Singapore is nothing if not diverse. The challenge will be to address certain contradictions, notably the perceived need for a stable consensus (which tends not to entertain deviant ideas) as against the need for a plurality of competing ideas and values if the country is to remain genuinely adaptive and innovative. This points to what some people believe is a fourth dimension to sustainability—political sustainability.

The Oliv Apartments (page 48) create a vertical landscape, the green common spaces providing natural cooling to the apartments.

New Homes for a New Society

The more things change, the more they stay the same. Despite the encroachment of a ‘global culture’ and its inherent stress on freedom, individuality and independence, in Singapore the family remains the foundation of society, and accommodating the extended family is a major preoccupation. Designing for the extended family, however, must now take into account changing cultural circumstances

As in other countries, escalating property values in Singapore make it increasingly difficult for younger generations to buy their own home. One solution has been to turn to the mass market, in particular the resale HDB apartment market where (as we see in the Dakota Apartment, page 156) there is a growing appreciation of the potential to renovate for a more up-to-date lifestyle, allied to an emerging sentimental attraction to a housing type once looked down upon. Another emerging solution is to buy into places like Johor Bahru and Sembawang in Malaysia, where land is more affordable, and to commute to the city.

Younger people living at home longer have provided a boost to the sustainability of the extended family and pleased the parents. But it comes with a rider because changing mores now require greater degrees of privacy and independence. The result has been a new form of multi-generational house, one which distinguishes far more clearly than before between the respective private domains. Adult children’s quarters now tend to be far more self-contained, often with their own entrances, allowing the children to come and go as they please without disturbing the rest of the household.

At the same time, greater flexibility is being designed into multi-generational houses, which is about designing for the next generation and for the future generally. On the one hand, the aim is to build in the ability to reconfigure the house as parents and grandparents age and as children grow up, and so allow for changing needs. Parallel to this is a preoccupation with resale value, leading to an avoidance of prescriptive design and enabling the house to remain attractive to future owners who might have different needs and values.

It may seem odd that decentralization should be a driver on such a small island. But as part of the strategy to spread density, relieve the pressure on both private and public transport and generally prevent Singapore from becoming an environmental pressure cooker, the government is constantly developing new and self-sufficient towns that complement a growing suburbanization. One result has been a more focused idea of urban living, especially among the younger generation.

The Bamboo Curtain House (page 162) opens up to the outside, as seen in the kitchen with its courtyard and greenery.

Again, this is impacting the direction of residential design, with people wanting to be part of the action and yet still having their own private refuge. For one market sector, conservation houses or other existing houses remain desirable, partly because of their proximity to urban attractions and partly because of their potential for interior redevelopment while retaining the aura of history and culture. For a less affluent part of the market, the resale HDB market is increasingly attractive, especially if it is in or near fashionable and well-located precincts.

We also need to consider the new kinds of clients who are emerging and whose residential requirements are different from an earlier generation. These include single people, couples without children or with only one or two children. There is also the expatriate market, not all of whom earn huge salaries but who have their own preferences. The Cranes (page 200) is one example of a possible new direction in catering to this sector of the market, while the Watten Residences (page 178) and The Green Collection (page 184) are two other distinctive terrace housing models that provide many of the amenities of a landed house but with cost offsets.

Models like these also represent new propositions for a sustainable balance between privacy and community. In Singapore, as elsewhere in tropical Southeast Asia, the relationship of privacy to community remains the single most important theme. If anything, the issue of balancing the two is even more important now than it ever was with the diversification of lifestyles reflecting the growth of cities and the continual development of a new world economic order.

Traditionally, of course, the issue has been how to attain a degree of privacy in a strongly communalist society. But the issue is now more nuanced. This more complex view of how privacy and community should coexist is well put by Tan Ji Ken, who worked with Mark Wee on The Cranes. In a note on the project he writes, ‘Privacy is an under-estimated catalyst for community. It creates security and a sense of having something of one’s own to fuel the courage and respite needed for productive and meaningful communal engagement. All the best community platforms have privacy settings.’

Another feature of Guz Wilkinson’s work is the tropical garden, which cools the house. Here in The Coral House (page 86), the garden is elevated off the ground.

For our lives to be sustainable, we need both privacy and community for a sense of belonging. At the very least, being part of a community helps us to shape our values and to define who we are. Historically, however, the emphasis has been on how we as individuals or as families can achieve a reasonable degree of privacy and refuge from the larger world without losing the benefits of belonging to the collective. The benefits are contingent on each of us bringing something to the table.

Arguably, we live in a world which is becoming more communal, more connected. With digital technology, it can seem as though there is no private space left and that we are all living in one gigantic public space. This begs the question: how meaningful is this connectedness, how genuinely engaged are we? Tan Ji’s point is important—productive and meaningful engagement in communal life is only possible when we approach it with the secure sense of self, which is generated in the private domain. In other words, it is a two-way street; we need both as privacy and community feed one another.

The opportunity to be together and yet separate is the big theme in tropical Southeast Asian residential design. For Singapore, it is especially crucial and key to the country’s sustainable future.

In this book, I offer a selection of projects ranging from free-standing houses to terrace houses and multi-residential projects to high-rise multi-residentials. Each is an example of one or more of the three key components of sustainability: environmental, social and economic. At the same time, the houses reflect a variety of changes taking place in modern Singapore.

My argument has been that sustainability is the key to Singapore’s future. In that sense, the high-quality luxury homes gathered together in this book illustrate how residential design is both contributing to and reflecting that sustainable agenda.