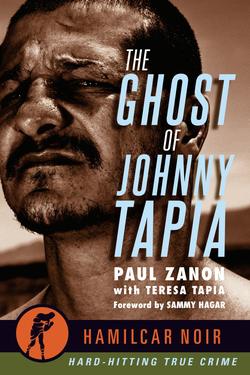

Читать книгу The Ghost of Johnny Tapia - Paul Zanon - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление

Foreword

My father boxed at bantamweight, featherweight, and lightweight, fighting under a variety of names, including Bobby Hagar, Bobby Burns, and Cotton Burns. He was always taking fights at the last minute, getting in trouble for being drunk in the ring and getting banned. He needed the money and would change his name every time he went to a new town to get a fight. When he started he was really good and had a strong punch, but he kept going downhill because he was an alcoholic.

As for me, from as young as I can remember, my dad would call me “Champ” and introduce me as that, telling everyone I was going to be champion of the world. He had a little gym set up in the garage, and I boxed all over the neighborhood. I was pretty much thinking that was what I was going to do with my life, although I do remember seeing Elvis Presley on TV and watching my older teenage sisters going crazy over him and thinking, “Maybe I'm going to be that.”

The turning point came when I was fifteen and a half. My dad took me to Los Angeles to the Main Street Gym, where Johnny Flores was training Jerry Quarry. We walked in and my dad said, “He's gonna be a fighter,” and Johnny said, “Let's see what he can do.” He put me in the ring with some Mexican guy, who'd had about thirty pro fights, and moments later this guy hit me. The moment it landed, I thought, “Man. I have never been hit like that in my life and I don't ever wanna be hit like that again!”

My dad had already applied for my professional boxing license and even lied about my age to get me the forms. After that sparring session, I went home and I was filling everything out, and my mom was crying as she watched. “You're not going to do that. You're not going to be like your father.” I stopped and said, “You know what. You're right.” My head was still ringing from that freakin’ left hook I took from this Mexican dude. That was it. I don't think I ever put on a set of gloves again.

• • •

Roll the clock forward to the 1990s and I'm at a David Tua fight in Vegas. Johnny Tapia comes up to me and says, “Hey. Sammy Hagar. The Red Rocker! I'm Johnny Tapia.” I replied, “I know exactly who you are!” Everybody knew who Johnny was. I then said, “Let's exchange numbers. It would be great to go to the fights together.” We exchanged numbers and he'd call all the time. Even at 4 a.m. “Hey brother. What's happening? You ain't giving me no love. I ain't heard from you for like a week.” He was always joking around, and you couldn't help but just love the guy.

Every time I'd meet with Johnny, there'd be a story to tell after. One time, I'm in Vegas, staying in a hotel and we're going to go to a fight together. I'm waiting in the lobby looking at my watch thinking, “Is he ever turning up?” About an hour later, his wife Teresa walks over and says, “We were here on time, but as Johnny was waiting in the lobby for you, some guy was giving the lady behind the desk some shit and Johnny went up to him and said, ‘Hey man. Stop being rude to the lady,’ and the guy said, ‘Fuck you.’ Johnny knocked the guy out in the lobby and his buddy took off running. Johnny took after him, then the cops arrived. So Johnny was late because he was filling out papers for the cops.” You had to love him for that.

Then in 2002, Johnny gave me the opportunity to do something I could have only dreamed of: working his corner. Not just any old corner though. I was alongside Freddie Roach, and Johnny was fighting the incredible Marco Antonio Barrera. When he asked me, I said, “Sure. But I don't know how to work a corner!” He said, “Don't worry about that, man.” I asked Freddie Roach what to do and he said, “Yeah. Don't worry. You just put the stool in there. You're gonna be the stool guy. You put it through the ropes, right before he comes over at the end of each round.” He gave me a little bit of coaching on how to do it and I thought, “Fuck it. Yeah. I'll work the corner.”

The problem was, Johnny wanted me there as a motivation guy to give him a pep talk in between rounds, because I'm high energy. I go to the dressing room where they are warming up for the fight and Freddie takes me aside and says, “Listen. Nobody says anything in the corner but me. You understand?” and I say, “Sure.” Johnny sees what's going on and loves winding Freddie up and says to me, “Sammy. When I'm in that corner, I need you to get me all pumped up.” Freddie's looking at me shaking his head saying, “I do all the talking.”

Johnny now starts his warm-up and is throwing his left hooks on the mitts. It was exhilarating to witness how fast and hard Johnny would throw those punches and how quick his feet were. I was like, “Holy shit.” I've been in a few dressing rooms before but I'd never seen anybody warming up like that. All of a sudden, bang, he dislocates his shoulder. Completely pops out of the socket. I'm thinking, “This fight is over.” Johnny moves his arm around, pops it back in. A minute later, it pops out again and Johnny once again pops it back in like it's a normal thing to do. I'm thinking, “This is crazy. I've never seen anything like this before.” I was so nervous and scared for him.

We then walk out into the crowd, which was incredible. The fight starts, and every time he came back to the corner he kept saying, “Sammy baby. You ain't showing me no love, man. I ain't feeling the love Sammy!” I'm looking at Freddie and then turned to Johnny a bit hesitant and said, “Go get him Johnny!” The truth is, I was thinking, “I really can't help this guy.” When you listened to one of the best trainers in the world in Freddie Roach and what he was saying, I just didn't feel I belonged there. My band was sitting ringside right behind me and I kept looking at them saying, “Oh fuck!” It's different being in the corner. Everything looks different than when you're spectating as a fan.

Back in the early days, in 1974, I opened with Montrose for The Who at Wembley Stadium, London, in front of about eighty thousand people. That was less nerve-wracking than being in the corner for Johnny. I've got goose bumps on my arms just talking about it right now. What an experience and what a privilege to have shared that time with Johnny.

• • •

The last time I ever spoke with Johnny was in 2009, when he was in the hospital in a coma from one of his binges. Teresa would call and put me on the phone to him, to see if he'd wake up. They'd even brought in a priest who was reading him his last rights, basically saying, “Yup. This is it. He's not going to pull out of it this time.” The doctors were ready to pull the plug, then about ten days into the coma, I'm chatting to him and he screamed, “I Can't Drive 55!” and he came out of his coma. That was the last time I spoke to Johnny, and that kind of summed up the man he was.

Johnny had incredible heart, was such a sweet man, but was also tormented. He had two sides to him. The sweetest, nicest guy, but then the other side that could probably kill you. He was tortured with his addictions, but Johnny was always pure emotion in that ring. In his heyday, with his speed and skill, he was one of the greatest bantamweight champs ever.

Sammy HagarSan Francisco, CaliforniaJanuary 2019