Читать книгу The Mourning Hours - Paula DeBoard Treick - Страница 9

Оглавлениеthree

The crowd dispersed, and the Hammarstroms reassembled in the infield, half of us sweaty and all of us satisfied.

“Watch out, shorty!” Johnny yelled, appearing from the dugout. I pretended to dodge his grasp, but he caught me by the arms and hoisted me to his shoulders. I shrieked while he ran the bases, my hands grabbing on to his neck for dear life.

“Be careful!” Mom called from somewhere, her voice lost in the darkness.

I screamed as Johnny gained speed, heading for home plate. I squeezed my feet against his chest, too terrified to look until he eased up and carefully deposited me on the ground. That was Johnny—rough and gentle at the same time.

It wasn’t until later, when we were gathered around the kitchen table dunking chunks of apple pie into bowls of soupy vanilla ice cream, that I remembered about Stacy. For a moment I hesitated to say anything, wanting to hold Stacy’s existence close, like a treasure gathered in my fist.

Johnny had finished giving Grandpa the play-by-play, and Grandpa was just about finished pretending to be interested in his analysis of Sandy Maertz’s triple, when I managed to get a word in.

“A girl named Stacy Lemke says to tell you hi,” I said.

“Who’s that?” Johnny asked gruffly, looking down into his bowl. His cheeks suddenly flamed pink.

I shrugged, trying to be casual. “Stacy Lemke. She has red hair and freckles.” She has creamy skin, the softest handshake in the world. She said I was adorable.

“That must be Bill Lemke’s daughter. He played for the other team tonight. Is she in your class, Johnny?” Mom asked.

“I don’t know,” he said, shrugging.

“Sure you do,” Emilie piped up. “Stacy Lemke? She used to go out with what’s-his-name, the Ships quarterback.”

I smooshed my finger into a drop of ice cream. “She says she goes to school with you.”

“Well, I don’t know. Maybe I’ve seen her around,” Johnny said. He brought his bowl to his lips, trying to drain the last of his ice cream into his mouth. Mom cleared her throat pointedly, and Johnny set the bowl back on the table.

“Bill Lemke, the tax attorney?” Dad asked.

“O-o-o-h, someone’s got a crush on you,” Emilie teased.

Johnny clanked his spoon against his bowl. “Shut up, that’s not true.”

Dad said, “He’s the guy who helped Jerry hold on to some of that land after Karl died. Decent guy.”

Emilie sang, “Johnny’s got a girlfriend.... Johnny’s got—”

“I said shut up, already.” Johnny stood up and Mom sent Emilie a warning look sharp as any elbow. I had to hand it to Emilie; she wasn’t a coward. She was a master at pushing Johnny right to his very edge.

“Look, she’s just some girl.” Johnny turned away from us. His bowl and spoon landed in the sink with a clang, and the back door slammed a few seconds later.

Mom called, “Johnny! You get back here!” but Johnny was already gone.

“What’s got into him?” Dad demanded, his voice caught between annoyance and amusement.

Mom shrugged, getting up to rinse out Johnny’s bowl.

Dad stood then and stretched, the same stretch he did every night when the day was just about over. “I guess it’s time for me to make the rounds one last time,” he announced. “I could use a bit of company, though.”

This was my cue. I stood, following Dad to the door for our nighttime ritual. Kennel trotted behind us to the barn, where I dumped out some cat food for our half-dozen strays and Dad walked up and down the calf pens, whistling and cooing to the youngest, reassuring them. “Hey, now, baby,” I heard him say, and the calves responded by tottering forward in their pens, all awkward legs and clunky hooves.

I waited for Dad in the doorway of the barn with Kennel rubbing against my legs. From this perspective, slightly elevated from the rest of our property, it seemed as if all we needed was a moat and we would have our own little kingdom. Our land, all one hundred-and-sixty acres of it, stretched away farther than I could see into the deepening darkness. On the north side of the property the corn grew fiercely, shooting inches upward in a single day. Beyond the rows of corn was our neighbor Mel Wegner, beloved because he let me feed apples to his two retired quarter horses, King Henry and Queen Anne. In the opposite direction, our cow pasture joined up with what had been the Warczaks’ property, until Jerry had had to sell most of it to cover legal and medical expenses. These days, the bank rented him part of the property for a chicken farm. Sometimes, when the wind carried just right, I could hear the confusion of a thousand chickens pushing against each other. Other times, days in a row might pass without us seeing any of our human neighbors.

Our house, beaming now with yellow rectangles of light from almost every window, was set back from the road by a rolling green lawn that Grandpa Hammarstrom tended faithfully. Peeking behind it, closer to the road, was Grandpa’s house, newly remodeled to be in every way more efficient than ours. On the east end, our property ended in a thick patch of trees that started just about at one end of the county and ended at the other, a green ribbon of forest that more or less tended to itself. In the middle of it all was our barn, which Johnny had been painstakingly repainting, plus our towering blue silo, the sleek white milk tank.

“Ready, kiddo?” Dad asked, appearing behind me. He cupped his hand around the back of my head, and my silky, tangled blond hair fell through his fingers.

“Race you,” I said, suddenly filled with the night’s unspent energy, and started back. Dad was a superior racing companion, pushing me to go faster and farther, but never getting more than a step ahead of me. We arrived breathless at the back door. Mom was alone at the sink now, and she turned to grin at us.

“Another tie,” Dad announced.

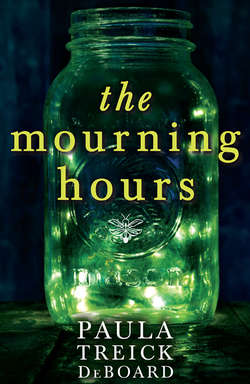

When I thought about this day later, I wished I could have scooped up the whole scene in one of Mom’s canning jars, so I could keep all of us there forever. I knew it wouldn’t last for that long, though—the fireflies I captured on summer nights had to be set free or else they were nothing more than curled-up husks by morning. But I had always loved the way they buzzed frantically in the jar, their winged, beetlelike bodies going into a tizzy with even the slightest shake. If I could have done it somehow, I would have captured my own family in the same way, all of us safe and together, if only for a moment.