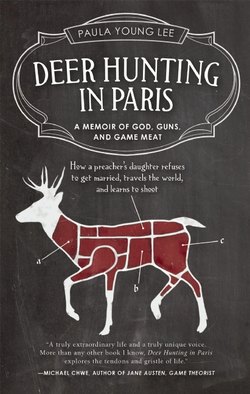

Читать книгу Deer Hunting in Paris - Paula Young Lee - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

“Keaton always said, ‘I don’t believe in God, but I’m afraid of him.’ Well I believe in God, and the only thing that scares me is Big Bird.”

—Verbal Kint, in The Usual Suspects, 1995

Parishioners believed he could heal them with his hands. As a kid, I knew my father was different, and it had nothing to do with the fact that he was a preacher. His legs were shriveled down to bone and he walked funny, sometimes with a cane. His face beamed. He forgot to eat. He liked Maine, because the rocky terrain reminded him of home. He and my mother came to the U.S. from Korea after the war. At first, there were four of us, and then there were five: my father, my mother, my brother, my sister, and me in the middle. My older brother and I fought mean and hard, locked in a death match from the day I was born. Oblivious to the slugfest, my baby sister sat back and let the adults admire her. She was the pretty one, and could never figure out why I was so furious all the time. She was born with grace. Predictably, her Korean name, Young-Mi, means “flower.” Mine is Young-Nan. It means “egg.”

Together, the three of us practiced our musical instruments, spoke English at home, and got straight A’s in school. We grew up ringing church bells every Sunday, pulling down the ropes and flying up into the belfry. My sister and I sang in the choir as my brother pummeled toccatas and fugues out of the organ. There was Sunday school, bible study, and neighborly visits to the nursing home, but the part I liked about church was Christmas, and the fancy food.

I could cook before I could read. I could read before I was four, because I was mad that my older brother was Sacred Cow Oldest Number One Son, and he got to do everything first. From birth, I knew the weight of karmic injustice, and I knew what that meant thanks to those theological discussions at dinner. Not only would I never be older than him, he would always be smarter. And a boy. His Korean name began with “Ho,” which in English means “Great.” Humph. What’s so great about him? “How come he gets to be a Ho?” I would howl, a pudgy ball of rage stamping angrily on tabletops. “It’s not fair! I want to be a Ho!” Sure, he could make electric generators out of Tinker Toy sets, but I could make layer cakes, and I had friends. So there. Cakes win.

With “Auntie” Ima the babysitter, I baked coffee cakes and apple pies. With my mother, I made mondu (dumplings) and nangmyun (noodles). The church ladies taught me how to knead dough and whip cream. I didn’t eat the goodies that I made. Nothing about me was sweet, including my teeth. My great food love was meat, the kind of meat that demands a sharp knife and a taste for blood. We never seemed to have much. I suppose we were dirt poor, but so was everyone else. Poor was normal. Poverty was too. Instead of plastic reindeer glowing on front yards, winter meant gutted deer hanging off porch roofs, hovering lightly in the blue air, black noses sniffing the ground. I’d extend a searching hand, flicking away flakes, and stick my nose in where it didn’t belong. Like magic, the deer’s length and heft became food and it was Good, the body and blood of Amen, a serving of flesh tying the community together through the violence of hunger.

Deer and hunter walked the same paths through the woods. I wanted to follow them.

Sunday dinners at the parsonage, guests would discard the gristle, the cartilage, the marrow, and the rind, all the stuff that pale priests and thickening colonels refused to touch in mixed company. I’d serve and clear the table, acting the perfect hostess as my baby sister sat quietly, basking in her cuteness, and my savant brother played young Christ before the Elders. Back in the kitchen where no one would see me, I’d grab bones off dirtied plates and gnaw off that bulbous white knob at the end, my favorite part, a tasty tidbit that only appeared after the commonplace had been excavated. Lollipops for carnivores. It wasn’t meat that I really craved. I loved liver and heart, along with the tangled tissues that connected the big sheets of muscle together. The offal fed to animals was the stuff I wanted to chew, because I was more contrary than Mary, not Mary mother of God but the stubborn one that ruled Scotland before she lost her head.

So, Mistress Mary, how does your garden grow?

Oh, very well, thanks to the corpse of my murdered husband fertilizing the marigolds.

Nursery rhymes mask vicious politics. So does a well-cooked meal.

A giblet was a meat pacifier, rubbery and melting at the same time. It resisted. It put up a fight. I cherished its toughness as I gnawed and glowered in the kitchen, a fat feral gnome surrounded by the aromas of love and yeast and holy ghosts I did not believe in.

“It does not matter if you believe in God,” my father said with infuriating patience. “Because God believes in you.”

“But I’m an iconoclast,” I protested loudly, trying out my interesting new word.

“So was Martin Luther,” my father responded placidly. “You’re a Protestant through and through.”

“No, I’m not!”

“Yes, you are.”

And so I was boxed into a corner.

At bedtime, my mom tucked me and my sister into our respective twin beds with matching quilts that she and the quilting bee ladies had made. Then she’d make me say my prayers. “Dear God,” I’d start obediently. And stop. Patiently, my mother waited while I struggled to free my arms from the leaden weight of white sheets so I could clasp my hands in the correct form, shaping them into a steeple pointing toward heaven. “Dear God,” I’d start again, with a heavy sigh. “Thank you for my mom, my dad, my baby sister,”—at which point, my baby sister would look like she just won a puppy—“and my brother who is the worst brother ever but I’m not supposed to say that so I’M NOT, and thank you for the really good turkey that we had for dinner tonight. Amen.” Satisfied, my mother would return my struggling arms back under the covers and re-tuck the sheets so tightly that I felt like a PEZ dispenser ready to poop out little turds of peppermint candy. Carefully, she’d turn out the light, plunging the room into darkness, and close the bedroom door behind her as she left to repeat the ritual with my brother, who got his own room, just like he got his own bike and his own underwear. Clutching her beloved stuffed animal to her chest, my sister would immediately close her eyes, fall asleep, and start drooling, not necessarily in that order. I would wait one, two, three seconds for her adenoids to be fully charged, and then I’d struggle free of my swaddling, grab the flashlight hidden beneath my pillow, reach for the books I’d stashed under my bed, duck under the covers, and start reading.

I slept on books too. To this day, I prefer a very hard mattress.

After regular services at our church, we’d sometimes drive out to visit the Bahá’ís because it was the neighborly thing to do. Who were the Bahá’ís? In 1900, a Maine woman named Sarah Jane Farmer had gone to Palestine by herself. When she returned, she established a religious retreat in Eliot, Maine, for the Bahá’í Faith. It’s the religious equivalent of cricket, the most popular professional sport in the world, but one that most Americans have never heard of and have no idea how to play. Bahá’ís believe in God, but their version has no gender. It’s basically what Christianity would look like if the Vatican hadn’t taken over the God business. Sarah Jane’s childhood home in Eliot, Maine, had been a mecca for the most progressive minds of the period, including Harriet Beecher Stowe and Sojourner Truth. Her father, Moses Farmer, invented the fire box pull and 99 other useful things including a useless toy called the “light bulb.” Along came this other guy named Thomas Edison, who had a genius for taking lame inventions and tweaking them so they could be mass produced and sold for a profit. This is what Edison did with the incandescent bulb, and he died a very rich man. Farmer believed that his gifts were God-given, and thus it was a sin to profit from them. Today, nobody’s heard of him.

What do we learn from this? Successful businessmen believe they are God’s gift to the world. They are correct.

To the great disappointment of my four-year-old self, the Bahá’í Faith congregation was made up of nice white folks with heavy Maine accents, same as the people who went to the Methodist church where my dad preached every Sunday. The grounds of the Bahá’í Faith retreat were magically beautiful, leading me to think that “Bahá’í” was the secret code word for “Narnia.” I was very disappointed when Mr. Tumnus the Faun did not appear, welcoming us with a turban on his head and a platter of Turkish delight in his hands. Apart from the fact that Edmund Pevensie liked to eat it very much, I had no idea what Turkish delight was, but it sounded very Turkish, and therefore I was keen to try it. I was hoping it was 100 percent giblets.

Even today, Turkish delight isn’t widely available in the U.S. I had to go all the way to France to discover that Turkish delight is a nut bomb of death disguised with a heavy dusting of confectioner’s sugar. By then, I was also old enough to have learned that C.S. Lewis, the Irish author of the Narnia chronicles, had been professor of English at Oxford University, and he’d nicknamed himself after his dead dog, Jack. He was also a theologian who’d infused the entire Narnia series with a Christian agenda aimed straight at convincing sweet, innocent children to believe in the Way and the Truth and the Life after Death for a large talking lion named Aslan. In case you’ve never noticed, “Aslan” is an anagram of “nasal,” which is another way of saying “nose,” which is to say, He who “knows” all. Oh . . . my . . . GOD. It’s a conspiracy! C.S. Lewis wrote a bunch of other books too, but those were for grownups. I’ll bet you can’t name one. Which just proves that the conspiracy theorists are correct, and God favors those who write fantasy books in His name.

“Aslan” is the Turkish word for “lion.” There is no lion meat in Turkish delight. There is no Turkish delight in the Aslan.

I read and re-read the Narnia books about a hundred times, because a set was in the library of just about every church my dad served. It was a lot. In small towns in Maine, churches are like Dunkin’ Donuts: there’s one on every corner, and they each have a membership of about a dozen. Because many of these churches were too small to support a full-time minister, some of my dad’s assignments turned him into a circuit preacher. I literally grew up in the church, but in my head, “church” was a collective set of white clapboard buildings that would have pitchers of red Kool-Aid and stale vanilla finger cookies in the kitchen refrigerators. As a little kid, I’d run around the vestry, hide in the pulpit, and stretch out and nap in the pews. Of course I knew I wasn’t supposed to, but God never reached down and smote me, even though I dared Him to. I took this as a sign He approved. The church was God’s house, but it was also my dad’s office and a building with a reliably flushing toilet. When dragged to visit the Catholics, usually because my dad had meetings with them, I’d grab a book and settle into an empty confessional. They were supposed to be locked when not in use, to prevent sinners from confessing to an empty box, but there’s that pesky road to hell separating the best of intentions from skeletons in the closet. Eventually, nuns would figure out where I was, and they always had this perplexed look on their faces, as if they couldn’t decide what I was really doing, sitting mostly in the dark with that musty old book about the Pilgrim’s progress on my lap. (Unacceptable answer: “Looking for Narnia.”)

These little escapades convinced me that nuns came with sagging stockings and wimples, which struck me as extremely appealing. I made up my mind to become one. This impulse didn’t last very long, because there was a war going on. There was also a war between the U.S. and Vietnam, and it was on the news every night.

“I’m going to become President of the United States!” I announced.

“Stop blocking the TV,” my brother complained.

“Make me,” I dared.

“Get out of the way,” my brother menaced. “Or else . . .”

“Nyah nyah!”

At which point, my baby sister would start crying, and I’d be sent to my room until my tantrum subsided. If I was the President, I reasoned darkly as I threw Barbie dolls across the room, no one could stop me from blowing up my brother. He was standing between me and my plans for world domination. To thwart me, he’d started booby-trapping the house so a loud buzzer would go off when I hit a hidden tripwire. BBBBBBBRRRRRRRGGG! Sometimes, for extra fun, the booby traps would zap me, so I’d shriek like a howler monkey and then hit the roof. He thought this was hilarious. I was not amused.

This is what happens when you have a mad scientist for an older brother. The adults admired him for being so clever, and I was ready to kill him.

It was just as well that my parents scuttled my political ambitions. I’m too short to win presidential elections. Plus, I’d never make it through vetting, because my mom’s name is wrong on the birth certificate. Being dead and all, she can’t sign a notarized affidavit stating that she’d given birth to me, no matter how many times the bureaucrats insisted that I drag her to city hall and make her deal with the paperwork. Since I don’t know any spells to raise the dead, I was left with the interesting proposition that, legally, I’m the child of a woman who didn’t exist.

With every passing year, I’m becoming more and more like her.

My father became a pastor because he’d been a Private First Class in the 9th Division of the Republic of Korea (ROK) Army, and he’d seen what the artillery fire had done to the land. The bombs ate everything green, and left nothing behind but ashes. The war was doing the same to the soldiers’ souls. My dad wasn’t a military chaplain, but he was a Christian, and soldiers who’d just lost their buddies in battle would ask him if he believed in life after death. If he did believe in the afterlife, what happens then? He responded by praying with them, and singing hymns, and studying the Bible, and resolving that he needed to deepen his understanding of God’s holy word. He followed his faith, and it brought him all the way from the Hermit Kingdom to Vacationland, USA.

Still walking on two legs, he traveled to the U.S. in order to study at a small Methodist university in Lincoln, Nebraska. Shortly after he arrived, he was invited to preach the gospel at a church in a town called Cozad. He didn’t have a car, so another student volunteered to drive him down that lonesome rural road on a frosty Sunday morning. By the time they saw the other car pulling out of an intersection that came out of nowhere, it was too late. The cars collided.

His friend escaped with a few cuts and scratches. My dad sailed out the front windshield and traveled fifty whole feet before landing. He was in a coma for a long time. When he woke up, the doctors told him he was a paraplegic, because his spinal cord was severed at the waist.

Despite the physical therapy, his legs shriveled due to muscle atrophy. He was in terrible pain. The morphine turned him into an addict. He wanted to kill himself but failed, because he couldn’t move without help. He became angry with God, protesting with rage. The hospital put him on suicide watch, and removed everything from arm’s reach that could be turned into a weapon.

He became even angrier and lost the will to live.

He was in the hospital for a year. It was a long, hard road, but eventually, for reasons that are his to tell, he made his peace with God, and now my father walks through the strength of that renewed faith. His physician said that my father’s recovery was beyond the reach of medical science, and his only explanation was some sort of divine intervention. The doctor was not a religious man. He didn’t believe in miracles, but what else was he supposed to call it? Me, I don’t think the miracle was the fact that my father regained the use of his legs, but that a young Korean man was spiritually adopted by the whitest bunch of white people that anyone could imagine in 1950s America, and they took him in, cared for him, and helped pay his medical bills. Students gave blood. Strangers pitched in. The entire community helped with his rehabilitation, as he went from mechanical bed, to wheelchair, to metal braces, to crutches, to a cane and finally to special boots that he still wears. If there was racism or bigotry in Nebraska, my father doesn’t recall it. That’s God working in mysterious ways. That, and a metal plate in his head.

He went on to study for the ministry at Boston University, where he met my mother, a Korean doctor’s daughter who’d come to BU to study nursing. She was pious, naïve, and problematically beautiful. They married in a traditional American white-dress ceremony, for she was Christian too, and carried on as stereotypical Asian graduate students. After a respectable amount of time had passed, they were blessed with my brother. He was the Only Begotten Son, a gift from the Heavenly Father, the answer to their heartfelt wishes and nightly prayers. Not only did he have all of his fingers and all of his toes, but he had an IQ so high that he was awake and aware straight out of the womb. Sort of like a cross between Chucky the Doll and Damien in The Omen.

About a year later, my mother knew she was pregnant again when she felt something kicking inside her belly with the fury of a trapped beast. Even as a fetus, I abhorred being stuck in one place, and I wasn’t going to let a partially formed brainstem interfere with my quest to be free.

For those who enjoy splitting hairs, I was neither born nor conceived in Eliot, but I can truthfully say I was gestated in that teeny town where my dad answered the call to serve the Lord. After being ordained in Boston, he accepted an appointment to a church that none of the other ministers wanted because even religious men have ambitions, and Maine is really cold in the winter. When he and my mother arrived in Eliot, they were an eager family of three. I was merely a pesky case of indigestion that, a few months later, popped out as a pesky case of indigestion with hair on its head.

Some of the congregation objected to my father being appointed to lead their church. Mind you, they were not racists. They had nothing against chinks, gooks, or slant-eyes, excepting, of course, the commie ones in ‘Nam. Without them Chinamen over there in Japan, MacArthur would have had to make do with fighting Russians, and they’re not nearly as much fun to shoot. They welcomed immigrants, just as long as they comes here legal and speaks good English. No, they objected to my dad’s . . . uh . . . his interpretation of the liturgy! They didn’t like the way he planned to run the service. Too many hymns. Not enough scriptural readings, plus he was using the Revised Standard Version of the Bible instead of King James. What are we, Unitarians?

Rather than compromise their religious principles, the objecting faction traipsed off, firm in their moral rectitude and taking their best church supper recipes for glazed ham. I imagine they started their own church, something like the “Rhythm Methodists,” because that would be a very American thing to do, starting your own denomination when the old one doesn’t suit you, and then making as many miracle babies as possible to fill up those pews. My father felt bad that some parishioners felt that way, but Jesus still loves you, and them, and as long as they were worshipping the Almighty, he had no cause to complain. He’d already been through an unpopular war, and had no interest in fueling another. God has a plan. It is not our place to judge His ways.

My mother, however, had her own feelings on the subject. She tended to get resentful. She talked to herself, and I have dog ears. I heard everything until I stopped listening. I still heard too much.

After my baby sister was born, Auntie Ima started helping my mother manage us kids. We were each a little over one year apart, and my brother was a state-certified genius who required full-time monitoring lest he dismantle the record player and build a satellite out of the parts. Because she could sit on him if necessary, Auntie Ima took charge of my brother, my mother watched my baby sister, my dad tended to his flock, and I was left to my druthers. In nearly every frame of my parents’ home movies, I’m the heel of a patent-leather shoe, a hem of a corduroy jumper, or just not in the picture at all. But when I came back from the twilight woods, I’d head to Auntie Ima’s house and launch myself into her bulk. She was very fat. Invariably, I’d find her and my brother planted in spindle chairs at the kitchen table, where he’d be munching a slice of homemade blueberry pie and working through equations. She’d be playing solitaire, keeping one eye on the cards and the other on his motorized doodads. She smelled like old lady lavender and her flesh was fresh bread dough, powdery soft and fluffy, as if pumped full of air. She didn’t mind that I’d pet her arm and play with the batwings as if they were kittens. She was over sixty, and had no use for vanity.

“I knew you before you were born,” she’d say to me. There is something very weird about that.

She and my Uncle Loren were German Protestants from Ohio. They were a childless couple and good church people, as my dad would say. My Uncle Loren was a bespectacled, retired GE man who was older than his wife. He’d been some kind of engineer, and he spent hours helping my brother perfect his sister-torturing devices. Not only did I end up harboring a visceral dislike of anything with an electrical current, I was banished from my brother’s basement laboratory after that time I tiptoed downstairs to peek, and all his gizmos exploded. This only served to increase my resentment, because he got new stuff for his lab, and I got in trouble even though I’d done nothing but stand on the steps and glare politely at him.

Still, despite the fact that I was hopelessly bereft of mechanical ability and quite possibly haunted by a poltergeist, I was Uncle Loren’s favorite, and he was mine. We were alike in our crabby natures and dislike of children. He didn’t want any, and neither did I. He was dour in the manner of a summertime Santa on a day when the elves were playing hooky, and he knew that I knew it and didn’t expect him to change. We were two grumpy old men sitting on the porch, drinking our glasses of ice water and watching the chickadees at the birdfeeder. It never really occurred to me that he was old. For that matter, it didn’t occur to me that he was a “he.” My Uncle Loren was the closest thing I had to a cat. I was four and he was bald, and we were best friends. I adored my Uncle Loren, because he never expected me to do anything. I didn’t even have to cook for him. He had Auntie Ima for that, and she was very good at it.

One day, he went to sleep and never woke up.

He’d died of a heart attack. I suppose he died without knowing he was dead. The adults were tiptoeing around the subject, trying to shield us kids, but of course I knew what death was. All kids do. On cartoons and television, people die by the dozens every day. I’d stared at paintings of crucifixions and martyred saints my whole life. I’d just never seen an actual human corpse. It was my first wake. He was lying in an open casket and I climbed up to inspect him. He was wearing an ill-fitting suit that struck me as being oddly formal for bedtime. There was a small smile on his face. He looked happy, which was not his usual expression, and that really confused me.

“He’s gone to Heaven,” my dad explained reassuringly, as my Auntie Ima sobbed loudly into a large embroidered hanky.

“No, he didn’t. He’s right here,” I complained. “If he’s gone to Heaven, shouldn’t he be Assumptioned?”

“That’s Catholic,” my brother corrected me, because he was a genius, and I was always getting my theological dogma wrong. “Protestants don’t believe in that.”

There’s a soul, and there’s a body. Unless you’re Mary, Mother of Our Lord Jesus Christ, or Christ the Savior himself, your body sticks around and gets stuffed full of embalming fluid so little kids can stare at you and wonder why you smell funny. I didn’t cry, because I wasn’t sad that my Uncle Loren had died. I was too angry at him. It was one more reminder that every positive comes with a negative, and every life demands death as its price. Uncle Loren was the one person I could count on to take my side. So God killed him, as if to say, “Defend yourself, already! What, you think being a little kid earns you a pass? A century ago, you’d be working full time in a factory and dead of dysentery by age six. So whine all you want. Boo hoo!” My dad had lived through two great tragedies, the Korean War and the car accident that destroyed his legs, which turned his life into Madame Butterfly meets The Sun Also Rises. I just had stupid allergies and an annoying older brother, whose very existence seemed to be God’s way of letting me know, “Yes, Little Egg, there is a Hell!” And then He cracks me on the head.

“He’s in Heaven,” my father repeated solemnly. “He was a good man.”

My Auntie Ima blew her nose loudly, and resumed blubbering.

The problem isn’t death. It’s the horrible feeling that something has been taken away. It’s Lucy van Pelt convincing Charlie Brown to kick the football, then—“AAUGH!”—she whisks it away. “You shouldn’t have trusted me, Charlie Brown,” she tells him smugly as he lands with a hard thump on the ground, mentally kicking himself for being such a chump. The joke is that he never learns. Again and again she persuades him with a sweet smile, “Kick the football, Charlie Brown!” and he keeps hoping that this time it will be different, and the ball will soar through the unseen goalposts, earning him cheers from the crowd and kisses from the Little Red-Haired Girl. He falls for the line no less than forty-two times. “You shouldn’t have trusted me,” Lucy reminds us. We know the outcome and yet, a teeny part of us still hopes that maybe, just maybe, forty-three is the charm . . .

AAUGH!

Sometimes I wonder how I would have turned out if my parents had raised me in Nebraska, a state that grimly warns you: “Equality before the Law.” This doesn’t mean equality in the eyes of Ms. Law, because she’s blind and therefore handicapped. Nope. It’s all about Procrustean justice, Tarantino-style, and if you don’t like it—go ahead, make my day: I’ll blow the head right off your oversized corn dog. Because my dad is a saint, his response to war was to pray for men’s souls. Me, if I was on a battlefield and my friends were being killed, I’d figure out an attack strategy, grab the best sharpshooters, and save my troops. I’d also be court-martialed for breaking chain of command and having my period, but, like, whatever. A girl’s got to do what a girl’s got to do.

My father says I focus on the flesh because I already know what happens to the soul after death, and so, it bores me. But he also thinks that in a previous life, I was General George Patton. Even at age four, I thought Heaven seemed suspiciously like the Emerald City in the Wizard of Oz series. Now that I’m sprouting gray hairs on my head, I still don’t believe in reports of “Heaven” because I’ve yet to read one of these “I’ve been to Heaven!”-type books that isn’t describing a Renaissance painting full of white people riding unicorns. Logically, Heaven ought to be a place where humanoids are conspicuously absent, not flitting around on butterfly wings as their golden hair flutters in the wind. I don’t believe in reports of alien abductions for the same reason, because the aliens from Planet Enema always look like Steven Tyler with a shaved head. An omnipotent, omnipresent, infallible God ought to be able to do better than cough up the judging panel for American Idol to populate the infinite Universe.

If Hell, as philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre famously declared, “is other people,” then all those authors who died on the table, went to Heaven, ran into grandma and grandpa, and got shoved out so they could return to Earth and tell us lesser mortals about it, are profoundly delusional. Hint: it’s not Heaven they visited.

After the funeral, I ran outside and lost myself in the woods while my parents tended to the mourners. I wasn’t some kind of feral child communing with the beetles. The basic point was to get away from humans. This would have suited my Uncle Loren just fine. He would have run away from all those soggy people too. Since he believed in Heaven, they should be glad, because his soul has achieved the perfect Eternal. Which means that all those weepers, sitting around snotting up their handkerchiefs, are mostly feeling sorry for themselves. Why? The guy in the coffin’s the one who got himself dead. You should be happy it’s not you.

Or maybe not.

We can’t talk about that. Let’s change the subject!

So I fled.

Here is the thing about my Uncle Loren that I wasn’t supposed to know: he’d been one of the loudest voices in the faction that got all riled up about the changes to the, ahem, liturgy. Deeply offended by the prospect of excessive hymn singing, he came to services because Auntie Ima made him. He sat, arms crossed and pouting in the pews. He stalked out after the services. He hated going to church when he could be comfortably napping. He scowled as he volunteered to shovel the church sidewalks. He frowned as he handed out programs to the new members at Sunday services. He glowered as he stood at the pulpit and read the extra scriptures he insisted upon choosing from Leviticus, the Old Testament book that fundamentalist Christians love, because it commands humans not to lie, spread malicious gossip, or wear cotton-polyester blends. More and more people started joining my dad’s congregation, and my Uncle Loren complained about that too, grumbling that maybe we needed to build a bigger church to hold all the new families, and what could he do to help?

In the end, he practically adopted us because he was, indeed, a good man, and Leviticus also commands: “The stranger that dwells with you shall be to you as one born among you, and you shall love him as yourself.” Yes, this verse is from Leviticus. It’s also from the New Testament Book of Matthew the Nice, because the Bible plagiarizes itself.

This is why my dad believes the Lord works in mysterious ways. It is also why my mother knew that the Devil does too.

Then we moved.

The Methodist Church moves its pastors around every few years. We ended up living all over the state, from the southernmost border to the northernmost expanses where the U.S. blurs into Canada. So when I say I’m from Maine, that’s about as specific as I can get. It’s also because I’m very bad at geography. Dyslexics can’t distinguish hither from yon. My other deficiencies include no sense of direction—a sense that, I will soapbox here, needs to be added to the other six (sight, smell, taste, touch, hearing, and ESP), then inspected and PASSED at the body factory before the manufacturer can make shipment. On top of everything else, I’m a statistical rarity: a female with color blindness. Color gives me real problems. For a long time, I had no idea I couldn’t see them, and neither did the grownups. They just thought I liked wearing mismatched socks. Eventually, I learned that the rest of the world didn’t see things like I do, and thought it normal to sort things according to their hue. What was wrong with me? The answer was simple. Frankenstein stuck Abby Normal’s rotten brain in my head. So I said: “Ixnay on the ottenray! Normal is overrated.” Atchoo!

Maine is full of interesting towns, such as Rome, Mexico, Oxford, Poland, Norway, Moscow—and, of course, Paris. It’s the globe in a nutshell, and it’s full of snow too! But our moves always took us to dying little towns with dreary names like “Brownville Junction,” not to be confused with “Brownville,” even though they’re two sides of the same town on the wrong side of the tracks. The state of Maine has a Greenville, but it’s brown too. Which makes it Maine’s version of Greenland: it’s not really green, but somebody insisted that it was, and the name stuck. In Greenland’s case, that “somebody” was a Viking named Erik the Red, who was probably blue but nobody is going to correct a very large man on the run for murdering a whole lot of non-colorblind people. I liked these drab towns where nothing much happened. I spent a lot of time staring intently at dirt, and this kept me plenty busy for years.

“Nothing” is still my best speed. It’s remarkable how much trouble a kid doing nothing can get into.

Around the age of eight, I ran across one of those lists that whittled down all the literature in the world into one hundred Great Books. I figured I should read them all and make up my own mind if they were any good, so off I trundled to the town library with my little red wagon, tracked down ten titles off my list, and hauled them to the front desk. “Hi Mrs. Lindner! I’d like to check these books out, please!” She opened up each book to the DUE DATE slip glued to the inside back cover, whacked down the stamper on the book, and sometimes, just for fun, she’d stamp my hand too. With my books piled in my wagon, I trundled back home, where I parked my books in the living room and started in on my chores. These included doing the laundry, making dinner, and pummeling my brother for control over the upright piano we were all three supposed to practice for at least an hour each day. Every once in a while, my mother would break up the fist fight and make us practice the dreaded four-handed piano pieces, which meant sitting next to my brother on the bench while my baby sister worked the pedals. At the sound of the music, my father would come out of his office, thrilled to the core at the sight of his prodigies draped on the piano as if it was an orca trained to give rides to Carnegie Hall. Then he’d turn around, go back into his office, and resume his conversations with God.

When I turned my gaze upwards, mine eyes did not behold His glory in the heavenly kingdom above. I saw the metronome parked on top of the piano, ticking like a time bomb next to the white floaty bustheads of Chopin, Beethoven, and Schubert. Mutely, they stared reproachfully at my square hands stamped with DUE DATE hitting all the wrong keys.

Tick . . . tick . . . tick. The metronome arm swung as stiffly as a pendulum in Wonderland.

One hour. Twenty minutes. Only ten minutes to go!

“Stop rushing!” my brother would howl in disgust. “You’re messing up the tempo!”

Then he’d shove me bodily off the bench and settle into the center, claiming the piano as his personal exercise equipment. Rubbing my offended bum, I’d hurtle upstairs and start sawing loudly on my violin just to drown out his interpretation of Chopin’s Mazurka in E Minor. Does he not understand the meaning of Lento, ma non troppo? We learned that years ago, I’d grumble to myself. Stupid brother!

Somewhat obviously, we never listened to pop music on the radio, because my brother had taken it apart and made it into a rocket launcher.

Thanks to the list of Great Books, I quickly developed the vocabulary of a fin-de-siècle aesthete obsessed with art and turtles. I also developed breasts. I don’t think the reading part was causative, or even correlative. It was just a coincidence that I was going through the Awful Eights and adolescence at the same time. However, the list does explain why I prematurely waded through Anna Karenina, the greatest novel ever written about a French-speaking Russian adulteress. I didn’t grasp the big themes but somehow, the story of her tragic affair put me off meat for almost two decades. It didn’t make any sense, but why does anyone expect that it should? Let’s just say that my sudden aversion to meat had something to do with the fact that all the women seemed to spend their time heaving their bosoms at innocent bystanders. The bystanders dined well on their free meal. All the women died.

I had a bosom in third grade. It seemed prudent to keep it to myself.

My parents did not understand my decision to become a vegetarian, especially since the fresh flesh of animals was the only food group I could safely eat. From almonds to zucchini, just about everything else produced unfortunate effects, ranging from discordant fits of sneezing to bouts of hyperactive screaming. Some of my earliest memories are of intense itching and being swaddled so I wouldn’t claw myself to bits. Using an old-fashioned washboard and wringer, my parents rinsed out daily dozens of cloth diapers dripping with diarrhea and frowned in confusion when my perpetual rash got infected because I was allergic to detergents. Fish? Allergic! Cats? Allergic! Sunshine? Allergic! Etc. For all that I was a surprisingly functional little kid, but being allergic to just about everything sets up a relationship to the world that is inescapably adversarial. You cannot take anything for granted, including God’s purported benevolence as he watches over the (hmmm . . . tasty?) sparrows. Me, I was being eyeballed by the Almighty of Abraham, the judgmental Old Testament God that was busy smiting sinners and turning unworthy women into pillars of salt. Sulkily sucking my thumb (not allergic. Safe!), I used to imagine that I was Lot’s wife reincarnated, which explained both my liking for salt as well as my instinctive aversion to marriage. It pissed me off that she was “Lot’s wife” instead of, say, Veronica or Betty. These things register when you come from a culture that keeps the family unit sorted by calling you “Oldest Daughter.”

Koreans don’t understand “vegetarian.” In general, people who’ve experienced starvation due to war find it odd when a willful child rejects a perfectly acceptable food group just because. What, no Spam with your eggs? But you love Spam! Dried squid is good! American chop suey is good! Aigu, aigu, my mother wailed. What is wrong with Oldest Daughter?

No eight-year-old has a food philosophy. Refusing to eat meat was just something I had to do. In retrospect, I am glad that my father was assigned to churches in tiny towns where psychiatrists did not practice, because in rural America, food allergies are still namby-pamby liberal myths, setting me up for exceedingly vexed relationships with human authority figures who insisted on making me eat home-grown tomatoes and hand-caught lobsters and did not connect the dots when I began crossly exploding into hives. Adding insult to injury, most of my allergies weren’t fatal. That would have been interesting. No, mine were the kind that merely damned me to the perpetual motions of misery: wiping snot off my nose, knobbling watery eyes, watching my tongue swell, lather, rinse, repeat. Boring!

My dream was to get away from grownups telling me to stop sneezing. My mantra was self-sufficiency, and I started going after it as soon as I was able to crawl. The faster I could learn to fend for myself, the sooner I could set out on my own. I started by running the back roads of Maine, observing the quirks of the local ecology: fiddleheads to eat, pine cones for weapons, and beer cans worth money if you redeemed them. I ran to get out of the house. I ran because I was jumping out of my skin. I ran so I could be alone, running on restless legs that walked in and out of homerooms, kicking bullies in the schoolyard and slamming my brother in the shins. My sister just sat back and watched me fight, blinking bewildered black eyes and sucking contentedly on cookies.

By the following year, we moved again, this time very far north to a town full of snow plows. Not only was Houlton the first town we’d lived in that had shops, it had a real downtown with a shoe store and a movie theater that showed Star Wars. I didn’t live there for very long, because school officials quickly decided that my brother’s brain was turning into a black hole, threatening to become a portal to another dimension. I thought this was super. I couldn’t wait for his cranium to become my own personal TARDIS. To prevent the impending rupture of the space-time continuum, school officials recommended “boarding school.” This was a peculiar institution that my parents had never heard of, but one that might kill a second bird—me—with one stone. My brother would attend Phillips Academy at Exeter, and I would attend the sister school, Phillips Academy at Andover. Insofar as I had no idea what boarding school was—the best approximation I could come up with was “orphanage,” in the manner of Oliver Twist—it never occurred to me that I wouldn’t be admitted. In fact, I was sure I’d fit right in, what with my thrift-shop clothes and constant begging for gruel.

Off I went, content in my mediocrity, thrilled that I was no longer going to show up in class and hear, “How come she’s so bad at math? Her brother is so good at it!” From now on, I would hear, “How come she’s so bad at math? Aren’t all Asian kids good at it?” No longer a specific failure, I was a generic one. Huzzah! If I was a dunderhead with numbers, however, I excelled at being ornery. Wherefore, I planned to use my excellent schooling to become an artist. To my parents, I might as well have declared: “When I grow up, I want to be homeless!” They hoped it was just a phase, like my sister’s purple hair or my brother’s garage rock band. But I wanted to do what I wanted to do, and figured that I had no claim unless I was paying my own bills.

This was my father’s influence. He loved cowboy westerns, so what little television we watched tended to have dialogue such as: “I got two bits and a buffalo hide. That enough to buy me South Dakota?” In the black-and-white world of my childhood, a “bit” was enough to make small-town dreams come true, and a dime could feed a family of five for a week. “God watches over . . . ,” “loaves and the fishes . . . ,” “manna from heaven . . . ,” etc. What can I say? My dad was plugged into the God hotline; miracles worked for him. He also drew a straight line between education and getting money to pay for . . . more education. One summer back home from boarding school, I’d been hoping to work as an agricultural laborer, because that’s how kids in Maine used to earn their allowances. To no one’s surprise except for mine, I was a lousy farm hand, because my wheezing scared the milk cows, and my hives scared everybody else. I was left with the next best option: auditioning for the role of Window Girl at the Dairy Queen. Solemnly, my father offered me the choice: I could work for minimum wage and end up with a few dozen dollars after taxes. Or, I could earn terrific grades and get academic scholarships for thousands. I was trapped by the implacable logic of numbers. For me, there was no escaping their maddening grasp: as a full-fledged member of the lumpenproletariat, I could barely handle addition, let alone offer a counterargument to Marxist theories of the labor-based marketplace. As a result, I ended up forever unable to make a perfect swirly cone, for some skills require a lifetime of practice, like producing flaky pie crusts or forging metal for swords. Amazingly, however, my dad’s plan worked and I ended up winning essay contests where scholarships were the prizes.

This is why Asian kids are good at school, because their parents trick them into believing that it’s a slot machine guaranteed to pay off if you keep feeding it. Where do they get such insane ideas? Along with just about every other cultural belief, the explanation can be found in the storyline of a fairytale. The Chinese ones go like this:

There once was a man named Wu Ch’in, who studied hard and became very learned but no woman would marry him, because he stank of fish. A soothsayer had predicted that Wu Ch’in would become a great man, yet he lived in poverty and drowned his sorrows in drink. Decades dragged on, and all the people who’d heard the soothsayer’s prophecy were dead of old age. Now, as it happened, the southern provinces were being plagued by a dragon. The Emperor issued a proclamation, calling on his people to help solve this problem. “Maybe Ch’in knows the answer?” the villagers mocked him. Roused out of his stupor by their kicks, Wu Ch’in realized that he did know the answer. So he got to his feet, bowed to the startled bullies, and staggered off to see the Emperor, taking advantage of the long walk to get sober. At the palace, he impressed everyone with his great learning. Conveyed into the Emperor’s presence, he shared the information that quelled the dragon and cured the Emperor’s bunions. In gratitude, the Emperor named him Imperial physician and gave him three beautiful wives plus a most valuable singing canary. Thus the soothsayer’s prediction came true, and Wu Ch’in became a great man.

Thanks to the Confucian tradition, the crabby intellectual saves the day and gets the girls. Here’s the part that counts: these girls couldn’t care less about the beefcake warriors who carried out the Emperor’s orders, because they’re just dragon fodder. It’s a good reminder that the game of love is rigged: if you want to win, you have to bribe the soothsayer.

No surprise, then, that Asian families like to have at least one scholar in the family, the same way that Irish families like one son to be a priest: they’re handy to have around in case there’s a supernatural emergency involving a soothsayer with a lisp. I enjoyed the studying part, and frankly I was temperamentally inclined to be a drunken bum, but my every attempt at the lush life was promptly smacked down by the better angels of my nature, otherwise known as “allergies.” Name a vice, and I’m allergic to it. In my defense, I’m also allergic to most virtues. Every time I tried to break the rules in the predictable adolescent ways—smoking cigarettes, drinking beer, attempting to inhale—I ended up with some weird side effect that made strangers scream at the sight of me.

Eventually, though not as quickly as you might think, I learned that I did not possess the skills to become an amiable pothead. My incompetence at behaving like a normal American teenager did not improve my mood. Making matters worse, my freakishly omniscient dorm mother failed to be bamboozled by clever ruses to throw parties in my room. Not only did Ms. Amster know exactly what I’d been up to, she figured that as soon as I sampled contraband substance X and extracted all the relevant data from the experience, I’d lose all interest in it, because what I was really doing was conducting a dorky science experiment on myself. Take, for example, cigarettes. I was allowed to smoke smugly for exactly one week, after which point my dorm mother informed my parents that I’d developed a few very bad habits, including failing physics, snorting hot chocolate mix straight from the packet, and smoking a pack a day of Marlboro cigarettes. My parents responded by giving me permission to smoke in my room. However, I was to stop with the hot chocolate business immediately. So I responded exactly as they expected, and studied until my eyes fell out of my head.

I passed the class by reading every physics book I could get my hands on and memorizing all the solutions to the sample equations, which made me the human equivalent of a parrot squawking “one plus one equals two!” (Don’t tell anyone, but the parrot can’t really add.) It was a perfect example of how a dyslexic kid can succeed spectacularly in school by learning all the wrong things, but none of the people in charge seemed to care as long as I gave them the answer they wanted. In Sunday school, for example, my takeaway from the story of Nebuchadnezzar, the king of Babylon, who threw Meshach, Shadrach, and Abednego into a burning pit of fire for defying his will, was that 1) a vegetarian diet makes you fireproof, and 2) to be a proper biblical villain, your name must be unpronounceable. I did not, however, correctly internalize that great piety is a virtue rewarded by God, and that I should practice praying fervently, just in case I too ended up tossed in a fire pit by an angry potentate—a fate that, given my congenital inability to worship rich people, was not as farfetched as it might seem. When a strange man came by my all-girls dorm at Andover and started giving out sexist, possibly feminist, but indisputably ugly t-shirts saying “Vote for Bush,” I asked him nicely to state his purpose. His name was George Bush, he said; he’d come by to visit the daughter of a family friend, and he was running for president. (Of what? The Rotary?) It never occurred to me to genuflect, because I was too busy mistrusting him, eyeballing him warily until Katie sauntered into the Clement House common room and drawled delightedly at the stranger, “Y’all are so nice to come and see me!” dispensing beauty-queen air kisses and pacifying “Uncle George” sufficiently that he forgot to sic the Secret Service on me.

This would have been a better story if George had accepted the cigarette I’d offered him while we were waiting for Katie to appear, but no. For several weeks, however, I wore the BUSH button he gave me, because I was too lazy to remove it from my sweatshirt. Meeting the future AAAUGH! didn’t inspire me to become a Republican, but shortly thereafter it dawned on me that puffing on cigarettes had turned me into a remarkable facsimile of him, shriveling my skin and stiffening my joints as well as killing off what few spare brain cells I possessed. (I later learned that, yes, I was allergic to tobacco, wherefore smoking it was a bad idea, and eating it was even worse.) So I was stuck with a conundrum. Should I quit smoking and make the adults think they’d won? Should I keep smoking, just for the pleasure of thumbing my nose at authority? My parents were horrified by my habit, but by giving me permission, they were counting on the fact that I’d be so dismayed by their approval that I’d immediately stop. The truly aggravating part was that I’d already decided to quit, but I didn’t want to give them the satisfaction of believing their ploy had worked. In the end, I decided that it made no sense to cut off my nose to spite my face, so I crossed cigarettes off the list and carried on with my science experiment on myself.

By the time I graduated high school, I’d managed to sample quite an assortment of youthful indiscretions, but in the manner of nibbling off a corner of all the pieces of chocolate in a Valentine’s Day box and putting each one back in their paper-lined spot with an airy look of innocence. Given that adults were always pushing foods on me that made me sick, I had no confidence that forbidden fruits were any worse for my system than, say, avocados or crab cakes. To my teenage self, ingesting beer-in-a-can was fraught with the same mixture of fear, hope, and anticipation that I felt before trying the fish eggs-in-a-tube that Anja from Norway received in a care package: even though it was ninety-nine percent likely that I was allergic, how would I know unless I tried it? Same went for Vegemite, Marmite, and Nutella®, exotic spreads that WASPs seemed to love but which landed me in the Infirmary, where I convalesced dyspeptically on a regimen of ginger tea and Saltines.

In the same spirit of doomed experimentation, my plan was to earn my high school diploma and be done with formal education forever, because I’d tried it, didn’t have much use for it, and decided that it was not for me. It irked me that adults were under the impression that I was of a cheerful temperament, whereas in reality I was a misanthropic ball of peevishness. It was almost as if I was two people in one body. I used to think that I’d been a twin in the womb, and I’d eaten the other one while it was still underdone. It would explain a lot, really.

So what’s a surly teenager to do? For lack of a better plan, I went to college. This was where the trouble really started, because my antisocial, colorblind self still really wanted to be an artist.

“Foolish human!” the angels giggled as they threw cold water on my dreams. And lo! I was drenched with new allergies—to ink, clay, and paint. I was a sex-change operation away from being a Bubble Boy, the doctors warned, because making art was extremely bad for my health. Unless I was prepared to move to Antarctica and make ice sculptures for penguins, I had some unpleasant realities to face.

Slowly, and rather against my will, I was turning into a scholar named Double Ch’in. Now all I needed was a dragon to slay. So I decided to go looking for the monster of my dreams. By the time I’d finished my undergraduate degree and started on a Ph.D., I’d begun waddling around small continents in sensible shoes, carting around my precious packet of toilet paper, sunscreen, and a jar of antihistamines. Disappearing for months and years, I burrowed into cities such as Florence, London, and Seoul, but mostly Paris, a place that bears remarkably little resemblance to the romantic fantasies spun about it. This was fine with me. I wasn’t looking for love, drugs, yoga classes or any other “girl” narratives attached to stories about free spirits bravely traveling alone. When your trips abroad are being paid for by your father/divorce settlement/publisher, you’re not free. You’re expensive. Besides which, I grew up foreign in a native country. From birth, you’re an alien being, a world traveler by default: dropped down the chimney by migratory storks.

In cities called Cosmopolitan, everyone is born of a bird. We are all the same kind, fine in our feathers but naked in our skins. Not all birds fly. Not all birds can. My mother prayed I’d run into a nice Korean boy and start making legally wedded babies. My father hoped my peregrinations would put me on the road to Damascus, where I’d see God’s truth and start preaching His word, writing letters to the Corinthians and voting Republican. I was Saint Paul’s namesake, after all. My parents had been expecting a boy, because apparently I’d been one in the womb. That’s what the baby doctors told them. I chose to disagree. Given my conversion when I saw the light, my destiny was to become an apostle. Failing that, my father was thinking accountant. A good career choice for girls. Ah, but in Latin, Paul also means “little,” which is what I ended up being. Or rather, very short. Sometimes wee, mostly Weeble. The wobble was incontestable.

I knew my mind, and it was strange. It disagreed with my body, and my body struggled to get away. Amazingly, wherever my body went, my brain went too, barking, “No meat for you!” Forced to obey, my flesh got its revenge by growing sea monkeys under my skin and refusing to get out of bed. I was living pallid in Paris when my mother surprised everyone by dying first. After that, I got sick of being sick. So I quit being vegetarian and started chomping down chickens with a cheerful “fuck you!” to the medical establishment. I lost twenty pounds in three months eating roasted birds, making up for twenty years of tofu, broccoli, and brown rice, “healthy” foods that, against all logic, made me sickly and obese.

And I was happy as I laughed without mirth, a laugh filling a body exulting as it animated flesh not of my flesh, the body and blood of the animal, a communion that transmutes water into wine and makes hot dogs, pork rinds, and buffalo wings a refuge of the sacred. Give thanks. It died for you. I was the killer of the sacred lamb, a sticker of the devil’s spawn, a milker of cows and the executioner’s song. I was a creature living in a damaged world that I could not heal. Why not? Let us not mince words: when we eat, we kill. Nothing lives in the stomach except death and fear.

This I learned after traveling the world, by myself, a girl with fallen arches and no sense of direction.

This I understood after my physician grandfather and his Middle of Five Daughters sickened with cancer in their stomachs.

Elderly, he did not resist. His end was peaceful. My mother was younger than most who will read these words. She got angry. It didn’t change the outcome. My death, when it comes, will be different. Because they both really died of regret, “if only . . .” gnawing away at their souls until finally, it consumed their bodies too.

“If” is the most dangerous word in the English language. It is the portal to lost dreams.

I studied the carcasses exposed by my teeth, mulled the pathways that brought them to my plate, and asked myself, could I take a life to serve my needs? But of course. It is childish to pretend otherwise. With every step we take, we destroy a universe. To ants, we are Beelzebub and Kali rolled into one: a towering free-range demon dancing on their graves. To flies, we are the Brave Little Tailor, capable of flattening seven in one blow. To wildlife, we are the Great Exterminator, eradicating untold billions of grain-stealing sparrows so vegetarians can boast that they’re not cruel to animals. Each exhalation of breath releases a hallelujah of poisons into the air. Every poopy diaper injects lush microbes into waters drunk by babes in the woods. Only dead things don’t kill on purpose. They only kill by accident.

Contrary-wise, I now insist on eating birds and mammals, preferably wild ones shot by the man I love but won’t marry, their bodies made into meat by our hands joined together. I don’t feel guilty about it, sez the girl for whom a bee sting is lethal. Death is the promise. It is an ineluctable truth, for Nature is a murderous mother offering food everywhere we look. I can’t pretend to be one with Her as I tromp up bleak mountains, tracking deer in hopes of filling the winter’s larder. Instead, I look at the sheltering sky and think, humbly and with gladness, I stand beneath the heavenly roof of God’s yawning mouth. When it closes, if it closes, it becomes the maw of Hell. When? Today? Tomorrow? Oh, but Apocalypse Now was thirty years ago. The fear rises. The hymns swell. I am hungry. Such is the human condition. We hope and despair, rejoice and revile, celebrate and curse the profane absurdity of being apes rigged up in angel’s wings.

Angels don’t eat. Apes covet meat.

I’m no angel. Not before, and not after. For I can walk, and run, and go places my father cannot on shriveled legs made of bone as he sits, peaceably, letting the light of God shine from his face.

He is a spiritual man.

I am neither.