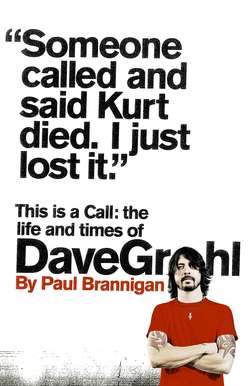

Читать книгу This Is a Call: The Life and Times of Dave Grohl - Paul Brannigan - Страница 7

Chaotic hardcore underage delinquents

ОглавлениеFor bands in Washington DC a career in music was never the intention. The motivation was, ‘Let’s get together and fucking blow this place up …’

Dave Grohl

On the afternoon of 21 January 1985 Ronald Reagan stood in the magnificent Capitol Rotunda for the swearing-in ceremony that would begin his second term as President of the United States of America. Re-elected following a landslide victory over Democratic Party candidate Walter Mondale, Reagan promised a new dawn for a nation emerging from the deepest recession since the Great Depression.

‘My fellow citizens, our nation is poised for greatness,’ he told the American people in his second inaugural address. ‘We must do what we know is right and do it with all our might. Let history say of us, “These were golden years …”’

In the same month that President Reagan was filling a cold January day with hot air, across the Potomac River, in Arlington, Virginia, a new band was formed. For vocalist Chris Page, guitarist Bryant ‘Ralph’ Mason, bassist Dave Smith and 16-year-old drummer Dave Grohl, Mission Impossible represented their own new beginning, as all four band members had previously played together in Freak Baby, one of the new acts who had emerged on the DC scene in mid ’84, around the time maxiumumrocknroll published its contentious ‘Does Punk Suck?’ issue. Freak Baby were by no means the best of DC punk’s second-wave bands – indeed Dave Grohl fondly remembers them as being ‘awful’. But the quartet were possessed of a boundless energy and a knack for short sharp shock pit anthems, the best of which (‘Love in the Back of My Mind’, ‘20–20 Hindsight’ and ‘No Words’) rang out like Stiff Little Fingers played at 78 rpm. In 17-year-old skatekid vocalist Page, Mission Impossible also had a frontman with genuine charisma and presence.

Now a married father of two working on environmental education projects in his native Seattle, Chris Page discovered punk rock in 1983, when he heard his Yorktown High School classmate Brian Samuels blasting Bad Brains’ self-titled ROIR cassette on a boombox in the school playground: ‘As with Dave, my dad left the family, and I was angry and confused at the time,’ he recalls. ‘And this was like nothing I’d ever heard before. I thought it was amazing, just incredible. That and the first Minor Threat record were my introduction to this world.’

Samuels helped Page navigate his way into Washington DC’s underground punk network: on weekends the pair would ride the DC Metro’s Orange and Blue lines from Rosslyn into the city to check out the scene. Page recalls his initial journeys into the heart of DC being ‘an adventure’ – ‘There’s all kinds of dark stuff in the city that you don’t see in the suburbs,’ he notes – and the shows being characterised by ‘pure, explosive, sweaty energy’.

‘There was definitely something special happening in DC at that time,’ agrees Hollywood film star and 30 Seconds to Mars frontman Jared Leto, who lived in the city from 1983 to 1984. ‘That scene was really vibrant, and the characters in it were such individuals. I worked in a nightclub right across the street from the 9:30 so I could walk in there every night and we saw some crazy shit. The shows were just free-for-all madness, with the singers jumping off the stage into the audience and passing the mic around. It was definitely a fun time.’

For Dave Grohl, the 1983 Rock Against Reagan show helped shine a light on this underground community. That July day was the first time he saw flyers advertising all-ages punk shows, hosted in off-the-beaten-track venues never listed in the Washington Post’s Arts section or DC’s newly established free listings paper the City Paper – hole-in-the-wall city centre clubs like dc space and Space II Arcade, suburban community centres such as the Wilson Center and hardcore gig-friendly restaurants such as Food for Thought in Dupont Circle. Emboldened by memories of his night at the Cubby Bear, he stage-dived headlong into the scene.

‘No one was sniping my neighbourhood with Black Flag flyers on the weekend,’ he remembers, ‘so initially that scene stayed pretty underground. But as soon as I found out about these shows I was like, “Man, if I could just get a ride …” All day long I’d mow lawns to make enough money to go into the city at the weekend: I’d have my Walkman on, blasting out Dead Kennedys In God We Trust and Bad Brains Rock for Light and Minor Threat’s Out of Step and the Faith/Void album and I’d be wondering what the weekend would have in store.

‘I’d get dropped off or take the Metro down to the shows in inner city DC on my own, and initially I didn’t know anyone. At that time in Washington DC there were three or four people getting killed every night over drugs: there was crack cocaine and a new drug called Love Boat – nobody knew what the fuck it was, it could have been embalming fluid, but you smoked it and it would burn white hot like an electrical fire and make you feel like you were sitting in your own blood for about four hours. It would make people kill each other. It was fucking crazy. So here I was, a 14-year-old kid on my own, on a Friday night in the murder capital of the world …

‘But then you’d go into these shows, and they’d be amazing. There was always the sense that anything could happen. There were people selling fanzines and people giving out stickers, and there’d be broken glass and fights and every once in a while someone would get stabbed. The venues were shitty, the PAs never worked and there were always technical difficulties, but you didn’t judge a band on performance as much as you judged them on audience participation. And your new favourite band could sound completely different than they did on the single you’d bought last week.

‘Trading tapes and buying singles and ordering fanzines by mail, all of those things became so special to you. You’d get a single by a band from Sweden in your mailbox and then a year later they were playing the shithole down the street? You can imagine the feeling: you’d walk in and see them in person and then they’d plug in and play the songs that you loved from that single that you ordered for two dollars a year ago and it meant the world to you, it was fucking huge. So that spirit, I consider it now to be just the spirit of rock ’n’ roll, that spirit of music meant more to me than anything else.’

On his trips into the city, two local bands in particular stole Grohl’s heart: Bad Brains and Virginian hardcore heroes Scream.

‘The first time I saw Scream was at one of those Rock Against Reagan shows,’ he recalls. ‘Scream was legendary in DC. They were from my neighbourhood, from Bailey’s Crossroads in suburban Virginia, which was maybe ten miles away from North Springfield, and if ever the DC scene seemed elitist or insular or hard to crack it didn’t matter, because Scream were from my fucking neighbourhood! We were so proud of that because not only were they one of the best American hardcore bands, but they were the best in DC: Bad Brains had moved to New York, Minor Threat were gone and Rites of Spring were amazing, but they weren’t playing hardcore. And Scream played everything. You would go to see them and they would play the first three songs off [their 1983 début album] Still Screaming, which are unbelievably bad-ass hardcore songs, and then bust into [Steppenwolf’s] “Magic Carpet Ride” and then do some weird space-dub shit for a couple of minutes and then pile back into something that sounded like Motörhead. They were so fucking good. They didn’t give a fuck what anyone thought of them, they didn’t give a shit. They were the under-dogs because they were from Virginia. And we looked up to them so much.

‘But nobody else blew me away as much as Bad Brains,’ Grohl admitted in 2010. ‘I’ll say it now, I have never ever, ever, ever, ever seen a band do anything even close to what Bad Brains used to do live. Seeing them live was, without a doubt, always one of the most intense, powerful experiences you could ever have. They were just … Oh God, words fail me … incredible. They were connected in a way I’d never seen before. They made me absolutely determined to become a musician, they basically changed my life, and changed the lives of everyone who saw them.

‘It was a time when hardcore bands were these skinny white guys, with shaved heads, who didn’t drink and didn’t smoke and made fast, stiff and rigid breakbeat noise. But the Bad Brains when they came out, it was like if James Brown was to play hardcore or punk rock! It was so smooth and so fucking powerful – they were gods, man, they were way more than human. To see that kind of energy and hear that kind of power just from a guitar, bass, some drums and a singer was unbelievable. It was something more than music and those four people onstage. It was just fucking unreal.

‘The DC scene wasn’t a huge scene,’ Grohl remembers. ‘If a local band like Scream or Black Market Baby or Void played you’d probably have maybe 200 people show up, the same 200 people every time: if you had a band like Black Flag play, then there’d maybe be 500 or 600 people there. We called those extra people the “Quincy Punks”, people who had seen one punk rock episode of [popular NBC crime drama] Quincy and then heard that Black Flag was coming to town. Those were usually the shows that had the most trouble. But the other gigs would have just a few people so you just started seeing the same people around. I’d be starstruck and intimidated when I would see, like, Mike Hampton from Faith or Guy [Picciotto], because these people were my musical heroes and I knew every word to every one of their songs, but you’d be singing along with a band and ten minutes later they’d be diving on top of your head when the next band was on. There was no separation between “bands” and “fans”, and that was my idea of some sort of community.

‘For me, punk rock was an escape, and it was rebellion. It was this fantasy land that you could visit every Friday evening at eight o’clock and beat each other to bits in front of the stage and then go home.’

It was at a Wilson Center show by Void, a chaotic, impossibly intense punk-metal quartet from Columbia, Maryland, that Grohl first met Brian Samuels in autumn 1984. At the time Samuels’s band Freak Baby were seeking to add a second guitar player to their line-up, just as scene elders Minor Threat, Faith and Scream had done the previous year, and Samuels invited the young guitarist to an audition at the group’s practice spot in drummer Dave Smith’s basement. Grohl wasn’t the best guitar player the band had ever seen – Chris Page remembers him as being merely ‘competent’ – but what he lacked in technical dexterity he made up for in terms of the energy, enthusiasm and infectious humour he brought to the band. In addition, Grohl’s simple but effective rhythm playing neatly complemented Bryant Mason’s more proficient lead guitar work. Freak Baby’s newest member made his début with the band that winter, playing as support to Trouble Funk at Arlington’s liberal-minded, ‘alternative’ high school H-B Woodlawn. It would prove to be the band’s one and only show as a quintet.

Freak Baby’s demise was sudden and brutal. One afternoon in late 1984 Grohl was behind Dave Smith’s kit at practice, trying out some of the rolls, fills, ruffs and flams he had been practising for years in his bedroom of his family home in Springfield. He had his head down, and eyes closed: his arms and legs became a blur as he hammered out beats to the Minor Threat and Bad Brains riffs running through his head. Lost in music, Grohl was oblivious to his bandmates urging him to get back to his guitar. Standing six foot five inches tall, and weighing in at around 270 pounds, skinhead Samuels was not a figure used to being ignored. Grohl didn’t notice his hulking bandmate rise from the sofa, so when Samuels yanked him off the drum stool by his hair and dragged him to the ground, he was more shocked than hurt. The rest of his band, however, were mortified. They had felt that Samuels had been increasingly trying to assert his authority and control over the band, but this was too much. As Grohl stumbled back to his feet, Chris Page called time on the day’s session. Within the week he would call time on Freak Baby too, reshuffling the line-up to move Grohl to drums, Smith to bass, and Samuels out the door. With the new line-up came a new name: Mission Impossible.

With the domineering Samuels out of the picture, initial Mission Impossible rehearsal sessions were playful, productive and wildly energetic: all four band members skated, and at times Smith’s basement resembled a skate park more than a rehearsal room, with the teenagers bouncing off the walls and spinning and tumbling over amps and furniture as they played. But there was also an intensity and focus to their rehearsals. Songs flowed freely as they bounced around ideas, fed off the energy in the room and experimented with structure, tone, pacing and dynamics. Just two months after forming, the band felt confident enough to record a demo tape with local sound engineer and musician Barrett Jones, who had helmed a previous session for Freak Baby. Jones fronted a college rock band called 11th Hour, North Virginia’s home-grown answer to R.E.M., and operated a tiny recording studio called Laundry Room, so called because his Tascam four-track tape deck and twelve-channel Peavey mixing board were located in the laundry room of his parents’ Arlington home. Now running a rather more sophisticated and expansive version of Laundry Room Studios out of South Park, Seattle, Jones has fond memories of the session.

‘I’d recorded a tape for Freak Baby with Dave on guitar, but when he switched to drums their band was just so much better,’ he recalls. ‘They went from doing one-minute hardcore songs to doing … two-minute hardcore songs! But those songs were more ambitious and involved and dynamic.

‘Back then Dave was probably the most hyper person I’d ever met,’ he adds. ‘When we did that first Freak Baby demo he was literally bouncing off the walls. They were a hardcore band, so they all had that energy, but he was something else. But musically his decision to switch to drums was definitely the right one.’

‘Once Dave got behind the drums he was very obviously something special,’ says Chris Page. ‘He was doing stuff that nobody else was doing, incorporating little riffs and ideas that he’d pinched from some of the great rock drummers he listened to. He took great pride in us being the fastest band in the DC area, but there was so much more to his playing than just speed and power. And that started to affect our songwriting, because even though our songs were maybe only one minute or a minute and a half long we wanted to showcase his talent and build in space for those parts.’

The first Mission Impossible demo neatly captured the quartet’s combustible energy. It provides a snapshot of a band in transition, mixing up vestigial Freak Baby tracks and goofy cover versions (most notably a take on Lalo Scifirin’s theme for the Mission Impossible TV series, with which the band opened every gig) with more nuanced shards of hardcore rage. Across twenty tracks the shifts in tone occasionally grate – the decision to include a screeching romp through a BandAids advertising jingle alongside a thoughtful, articulate song such as ‘Neglect’, in which Page delivers a spoken-word lyric juxtaposing the privileged consumer lifestyles of the suburbs with the poverty and pain he encountered on visits to inner-city DC, rather betrays the quartet’s youthful over-exuberance – but at their best Mission Impossible were a genuinely thrilling prospect.

Among the more light-hearted selections on the tape, two tracks stand out: ‘Butch Thrasher’ is Grohl’s mocking paean to the macho knuckledraggers who considered punk rock moshpits their private battlefields, while ‘Chud’, inspired by the kitschy 1984 horror movie C.H.U.D., sees Page screaming ‘Chaotic Hardcore Underage Delinquents! Cannibalistic Humanoid Underground Dwellers!’ while trying to keep a straight face. Of the more sober tracks, ‘Different’ deals with the hassles devotees of punk rock faced from parents and peers unsympathetic to the lifestyle, while ‘Life Already Drawn’ echoes the sentiments Ian MacKaye expressed in the song ‘Minor Threat’ with Page screaming ‘Slow down!’ at teen peers who seemed in an unseemly haste to join the adult rat-race.

Two Dave Grohl-penned originals also warrant mention: ‘New Ideas’ stands as the fastest song in MI’s repertoire, packing whammy bar divebombs, squealing harmonics, two verses, three choruses and a jittery, atonal Bryant Mason solo into just 74 seconds. Elsewhere ‘To Err Is Human’ was arguably the demo’s most sophisticated track, its driving rhythms and sudden dynamic shifts in tempo and key bearing the influence of Grohl’s favourite new band, SST’s Hüsker Dü, the brilliant Minneapolis trio whose stunning 1984 double album Zen Arcade had rendered hardcore’s perceived boundaries obsolete, and drawn favourable comparisons to The Clash’s London Calling album in mainstream music publications. ‘To Err …’ was significant not only for highlighting the increased maturity of Grohl’s songwriting, but also for flagging up to his new friends issues in his personal life, specifically in regard to his relationship with his father.

Over the years Dave Grohl has stubbornly resisted journalists’ attempts to play amateur psychologist over the impact his parents’ divorce had upon his life. It would make for a convenient narrative if his drive, energy, work ethic and subsequent success could be linked back to a teenage desire, conscious or subconscious, to scream ‘Look at me now!’ at the man who walked out on his family; if his entire artistic raison d’être could be traced back to the rejection, resentment, anger and pain he felt as the child of a broken home. But time and again Grohl has rejected this analysis. ‘There was some Nirvana book that glorified my parents’ divorce as if it were my inspiration to play music,’ he protested in 2005. ‘Completely untrue. The fucking Beatles were the inspiration for me to play music.’

Nevertheless, Dave had James Grohl in mind when in spring 1985 he scribbled the lyrics to ‘To Err Is Human’ in his notebook: ‘To err is human,’ he wrote, ‘so what the fuck are you? Working so hard to make me perfect too …’

At the time, Grohl’s visits to see his estranged father in Ohio were regularly punctuated by finger-pointing lectures, explosive arguments and sullen, protracted silences. As a speechwriter for the Republican Party, James Grohl was a master of the dark art of transforming trenchant opinions on morality, ethics and law and order into screeds of fiery rhetoric, and he was never shy of sharing his views with his teenage son, regardless of whether Dave wanted to hear them or not: ‘Imagine the lectures I’d get if I fucked up,’ Grohl commented in 2002. ‘I’d get the State of the Union address!’

With his grounding in classical music, James had firm views too on the self-discipline required of performing musicians – ‘He thought that unless you practised for six hours a day you couldn’t call yourself a musician,’ his son once noted – and Dave’s basement thrashings didn’t exactly match up to his lofty ideals. Even after Nirvana’s Nevermind album became a worldwide phenomenon, Dave Grohl was still mindful of his father’s occasionally dismissive attitude to his career. ‘Dave and I were at his house one night,’ his friend Jenny Toomey told me during the research for this book, ‘and I remember him talking about his father being critical of him for not being a “real” musician and I thought that was really sad,’ so one can only imagine the snarky, offhand comments that would have been directed towards him during his formative years in the DC punk underground.

During these difficult times music provided Dave with both a pressure valve and an escape hatch. His spirits were buoyed as Mission Impossible’s demo quickly built up a word-of-mouth buzz on the tape-trading underground, attracting plaudits both nationally and overseas. The band were name checked by maximumrocknroll editor Tim Yohannon in a review of Metrozine’s DC area cassette compilation Can It Be? (which featured MI’s ‘New Ideas’), and secured their first international release around the same time when French punk rock label 77KK included ‘Life Already Drawn’ alongside tracks by D.O.A., California’s Youth Brigade, Red Tide and the best up-and-coming French punk acts on their début release, a compilation album also titled 77KK.

In April 1985 Mission Impossible returned to Laundry Room Studios to cut a second demo. The quartet were now writing collaboratively, pushing one another to create more complex, challenging material, and a new-found self-assurance shone through in each of the six new tracks demoed with Barrett Jones. Hardcore’s ‘loud fast rules!’ ethic still provided a foundation for the new material, but MI had learnt that silence and space could be harnessed to accentuate volume and weight as readily as thrashing powerchords. Chris Page was growing in confidence as a lyric-writer too, and the conviction with which he delivered each word rendered his tales of teenage travails wholly believable.

Of the songs on this second demo ‘I Can Only Try’ is a classic slice of teen angst (‘I can’t promise perfection, I can only try’), ‘Into Your Shell’ is a rallying call for noisy self-expression (‘If you’re really upset and you don’t know what to do, then shout it out or talk it out, don’t crawl into your shell’) while ‘Paradoxic Sense’, ‘Wonderful World’ and ‘Helpless’ tackle issues of growing up without giving in. The demo’s final track, ‘Now I’m Alone’, finds the singer picking over his father’s decision to leave the family home – ‘You could say that disappointment with fathers was a minor theme with MI,’ Page now wryly reflects – and celebrating the freedoms that came with his immersion in the DC punk community.

Delivering fully on the promise of their first demo, the tape showcases a committed, articulate, progressive young band gearing up for adult life with defiant self-belief: ‘Now I’m off to face a new horizon,’ Chris Page sings, ‘but I don’t think I’ll be alone.’ These words would carry an added emotional resonance in the months ahead.

In spring 1985 unmarked envelopes were pushed through the letter-boxes of a number of homes in Washington DC and suburban Virginia. Each envelope contained a photocopied leaflet, styled to resemble a kidnap ransom note, bearing messages such as ‘Wake up! This is … REVOLUTION SUMMER!’ and ‘Be on your toes. This is … REVOLUTION SUMMER’. Recipients of the letters were initially bemused, then intrigued, curious not only to discover the identity of the anonymous letter-writer and the meaning of the note, but also as to who else might have received one. A common thread quickly emerged: everyone sent a ‘Revolution Summer’ missive had been active on the DC hardcore scene at the beginning of the decade.

The letters were traced back to the office of the Neighbourhood Planning Council, a small administrative body set up by the DC Mayor’s office to host community meetings and schedule an annual free summer concert series in nearby Fort Reno Park. Located next to Woodrow Wilson High School, the office had become a de facto drop-in centre for local punks to hang out and drink sodas. While they were there they had access to Xerox machines in order to run off flyers, posters and fanzines. It subsequently emerged that the letters had been sent out by Dischord staffer Amy Pickering as a playful way to get old friends talking together once again.

The plan proved extremely effective. Pickering’s missives opened up new dialogues among the hardcore class of ’81, who began mulling over their own involvement in the punk community, debating whether it was the scene, or they themselves, that had changed with the passing years. They wondered if, and how, the idealism and integrity that had fuelled that nascent community could be rekindled. As these conversations continued, many within the group made a conscious decision to try to redefine their world. Some started new bands, others formulated new ideas and made renewed commitments to re-engaging with the social and political issues affecting their community. As Ian MacKaye explained to Suburban Voice fanzine in 1990, the phrase ‘Revolution Summer’ itself meant ‘everything and nothing’, but it was the ‘kick in the ass’ he and his friends needed.

‘We all decided that this is it, Revolution Summer,’ MacKaye told the fanzine. ‘Get a band, get active, write poetry, write books, paint, take photos, just do something.’

For Beefeater frontman Thomas Squip, another resident of Dischord House, Revolution Summer was more than just a time of musical rebirth. As he explained to Flipside in a July 1985 interview, he considered Revolution Summer to be about ‘putting the protest back in punk’. The Swiss-born singer was soon backing up his words with action. That same month he helped organise the Punk Percussion Protest, a noisy anti-apartheid rally which saw scores of young punks gather on Massachusetts Avenue to bang on drums, buckets and bins outside the South African Embassy. Soon, in close co-operation with newly formed activist group Positive Force, DC punks – including the members of Mission Impossible – were lending their voices to a wide range of causes, from protests against America’s clandestine war in Nicaragua to benefit concerns for civil liberties organisations, community clinics and homeless shelters. Chris Page remembers the time as ‘eye-opening, empowering and transformative’. With delicious irony, DC punks were taking Reagan’s ‘we must do what we know is right and do it with all our might’ words to heart, and using them in opposition to some of his most reactionary policies.

In June the new wave of DC punk was showcased by a seven-inch compilation, put together by Metrozine editor Scott Crawford in collaboration with Gray Matter man Geoff Turner’s label WGNS. Its title, Alive & Kicking, was intended as a defiant rebuttal to those hardcore zealots who considered the DC scene as dead as the American Dream. Crawford selected for inclusion Mission Impossible’s ‘I Can Only Try’, alongside tracks by Beefeater, Marginal Man, United Mutations, Gray Matter and Cereal Killer: once again, over in Berkeley, maximumrocknroll gave positive feedback.

That same month also saw the release of the first record on Dischord for two years, the first, in fact, since Minor Threat’s Salad Days single. The self-titled début album by Guy Picciotto’s Rites of Spring could hardly have been more symbolic of the scene’s regeneration.

By common consent, Rites of Spring were Revolution Summer’s most inspirational band. They sang of love, loss, wasted potential and spiritual rebirth while attacking their instruments with a commitment, intensity and kinetic fury that saw guitars and amps reduced to matchwood. Their wiry, sinewy, high-tensile compositions eschewed hardcore formulas, choosing instead to strip away the genre’s machismo in order to expose its raw, sensitive, bleeding heart. RoS shows were genuine events that saw audiences moved to tears by the group’s passionate and cathartic outpourings. They would play just fifteen shows in their short history, and Dave Grohl says that he was present at every one of them.

‘A lot of people don’t realise the importance of that band, but for us they were the most important band in the world,’ he remembers. ‘They really changed a lot in DC. They played every show like it was their last night on earth. They didn’t last long, but then for bands in Washington DC a career in music was never the intention. The motivation was “Let’s get together and fucking blow this place up, until we can’t blow it up any more.” Once the inspiration or electricity felt like it was fading, or once a band started to feel like a responsibility, they’d just break up. It was all about that moment. But those moments were so special to us.’

July 1985 also saw the return to the stage of DC hardcore’s spiritual leader. Ian MacKaye’s new band Embrace may not have been as musically adventurous as Rites of Spring, but they were a powerful, emotive unit in their own right. As with his previous band Minor Threat, Embrace asked a lot of questions, but this time MacKaye’s rage was for the most part directed inwards, as he dissected his own foibles and flaws in unflinching, forensic detail. In part, this soul-searching was sparked by MacKaye’s admiration for DC’s younger punk set. When he looked at bands such as Mission Impossible and their peers Kid$ for Ca$h and Lünchmeat, MacKaye saw a new breed of idealistic, gung-ho teen punks operating in blissful, stubborn denial of hardcore’s demise, a poignant echo of his own reaction to premature reports of the death of punk rock: it made him wonder at what point he stopped believing. ‘Those kids were super enthusiastic and it reminded us of our younger selves,’ he recalls. ‘It was inspiring to see high school kids playing again.’

‘The American hardcore movement may have been all over by 1984, but none of us wanted to believe it,’ admits Lünchmeat vocalist Bobby Sullivan. ‘It was hard for us to measure up to what had already happened, but we were all fans of Minor Threat and Bad Brains and we wanted to carry on the tradition, in the right way.’

Dave Grohl and Bobby Sullivan were regular visitors to Dischord House in the summer of ’85. Ian MacKaye had known Sullivan for years, as he was the younger brother of his former Slinkees bandmate Mark Sullivan, and he remembers Grohl as a nice kid to have around, always positive, friendly and full of enthusiasm. He first saw the pair’s bands play together at a tiny community centre in Burke, Virginia that July. For all the positive energy surrounding Revolution Summer, a number of prominent venues, including the 9:30 Club and Grohl’s beloved Wilson Center, had that summer stopped booking hardcore bills due to the attendant violence and vandalism. Lake Braddock Community Center in the new-build community of Burke had emerged as a new venue after Kid$ for Ca$h guitarist Sohrab Habibion persuaded his mother to sign up as a sponsor to allow him to use the hall for all-ages shows. In keeping with the inclusive vibe of these gigs, the new venue lacked even a stage, the division between the audience and performers having been distilled down to nothing more prohibitive than a line of duct tape marked on the ground. Mission Impossible and Lünchmeat shared this ‘stage’ for the first time on 25 July 1985; Ian MacKaye was in the audience to see them.

‘Everyone said, “You gotta see this drummer, this kid, he’s 16, he’s been playing for two months and he’s out of control,”’ MacKaye recalls. ‘And then I saw them, and Dave was just maniacal. He didn’t have all the chops down, but he was dialling it in from the gods, his drumming was so out of control, and he wanted to play so hard and so fast, it was kinda phenomenal. Everybody was like, “Woah, that guy is incredible!”’

‘One night Ian came up and told me that he thought I played just like [D.O.A./Black Flag/Circle Jerks drummer] Chuck Biscuits,’ recalls Grohl. ‘To me that was like saying, “You are just like Keith Moon,” because Chuck Biscuits was a huge inspiration to me. So from then I became that kid in town who played like that, I had this reputation as being this super-fast, fucking out-of-control hardcore drummer.’

‘Honestly, from the moment you saw Dave play, you were just in shock, because he seemed superhuman,’ laughs Sohrab Habibion, now playing guitar in the excellent Sub Pop post-hardcore band Obits. ‘I liked Mission Impossible, Chris was a really cool singer and they had great songs, but you’d see them play and there’d be this monster on the drums. Dave sat in with my band Kid$ for Ca$h for a couple of shows and it was hilarious, because the whole band was instantly transformed to a higher calibre. We played one show out at Lake Braddock with 7 Seconds and they were all just staring at him, like, “Who is this guy?”’

‘People definitely talked about him,’ agrees Kevin Fox Haley, a Woodrow Wilson High School student at the time. ‘Everyone would say, “You gotta see this kid on drums, he’s insane.” To me it seemed like it stemmed from hyperactivity, because he was kinda a spazz, and I don’t mean that in a bad way, but he was so goofy and full of energy. I’m from Washington DC and I’m sorry to say that myself, and some people from Dischord, were pretty snobby about looking down on the kids from the suburbs, so maybe at the time I was still stuck in that snobbiness where I was like, “Yeah, he’s good, but he’s from out there …” But he definitely stood out.’

For all the momentum and buzz accumulated by Mission Impossible, their days were numbered. As with so many DC bands before them, the lure of higher education was to prove irresistible. Around the time the quartet recorded their second demo tape Chris Page had been accepted to study at Williams College in Massachusetts, while Bryant Mason had been offered a place at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, meaning the break-up of the band was inevitable. Mission Impossible played its final show at Fort Reno park on 24 August alongside local art-punks Age of Consent, preceded by one last emotional show with Lünchmeat at Lake Braddock, at which the two bands decided to cement their friendship by releasing a posthumous split single. A co-release between Dischord and Sammich, a label set up by Ian MacKaye’s younger sister Amanda and her Wilson High School friends Kevin Fox Haley and Eli Janney, the EP featured three tracks taken from Mission Impossible’s April ’85 demo – ‘Helpless’, ‘Into Your Shell’ and ‘Now I’m Alone’ – alongside three Lünchmeat originals – ‘Looking Around’, ‘No Need’ and ‘Under the Glare’. As the summer drew to a close, both bands and the Sammich kids commandeered the Neighbourhood Planning Council office to cut out, fold, paste and hand-decorate sleeves for the EP. For Grohl and his friends it was a bittersweet experience. Everyone involved in the project understood that both Mission Impossible and Lünchmeat had more to offer, but the young musicians remained positive and optimistic to the end, writing slogans such as ‘Revolution Summer is for always!’ on every sleeve. As a final gesture towards the community which had nurtured, supported and empowered them both as individuals and as bands, they decided to title the EP Thanks.

‘The Do-It-Yourself element made everything more special,’ Grohl recalled in 2007. ‘When your band put the money together to go into a studio, record some songs, take the tape, send it to the plant, get a test pressing, print the labels and stuff the sleeves yourselves, the final product in your hand is just amazing. Because you know you built that shit from scratch from the ground up.’

The sun had set on Revolution Summer long before the Thanks EP received its first review. Writing in the March 1986 issue of maximumrocknroll, reviewer Martin Sprouse commented, ‘Both outfits create and exhibit three high energy melodic thrashers backed by interesting lyrics. Neither outfit falls into the DC stereotype of musical direction but really do break the ice for a lot of the underground bands from that area. Worth looking into.’ By then of course both bands were already defunct.

When all 500 copies of the Thanks EP sold out, it was re-pressed and re-released under the rather more punk rock title Getting Shit for Growing Up Different. The new title was all too apt for Dave Grohl. His relationship with his own father James hit its lowest point around the same time, when Virginia Grohl informed her ex-husband that she had found a bong belonging to their son under the driver’s seat of her Ford Fiesta prior to a morning school run. Grohl and Jimmy Swanson had discovered marijuana around the same time they fell in love with punk rock and thrash metal: they embraced the herb with equal vigour. Unbeknown to his father, by 1985 Dave was also partial to huffing lighter fluid and necking hallucinogenic drugs. During one memorable Christmas party at Kathleen Place he was tripping on mushrooms to such an obvious degree that one of Virginia Grohl’s friends steered him away from the other revellers and politely enquired if he was doing cocaine. But pot remained his drug of choice: ‘I was smoking all day long,’ he admitted in 1996. ‘I was such a burn-out. My best friend was the bong. Me and Jimmy were bonded in pot; bonded by herb.

‘The first time I took acid was in Ocean City, Maryland in 1985,’ he recalls. ‘I was forced to take it. All of my other friends had taken it. They were like, “Come on! Take it! Take it!” I said, “I don’t want to take it,” and they said, “If you don’t take it we’re just going to put it in your drink,” so I said, “Okay, I’d rather know I’ve taken it.” I liked it so much I took another about six hours in …

‘When we were teenagers, me and Jimmy were outcasts,’ he laughs. ‘We weren’t jocks, we weren’t nerds, we had created our own little world: we were all about mischief and just being petty criminals. I’m sure most people thought that we were freaks, or just uncool: we were incredibly weird and geeky but we never gave a fuck. Being “cool” in suburban Virginia was like how big of a bong hit you could take. It didn’t matter what haircut you had, or what car you had, or what pants you had on, if you could burn a whole bowl in one bong hit, you were fucking cool.’

When James Grohl looked at his son in 1985, though, he did not see Virginia’s coolest teenager. Instead he saw a smart kid whose future seemed literally to be going up in smoke. He was concerned that Dave’s teenage rebellion was rooted in deeper psychiatric problems, perhaps linked to the break-up of the family unit a decade earlier, but two sessions with a guidance counsellor failed to divine any underlying issues. In a last resort attempt to impose some much-needed discipline on the boy, it was decided that Dave should transfer from Thomas Jefferson High to Alexandria’s Bishop Ireton High School, a Catholic private school, run by priests from the Religious Congregation of the Oblates of St Francis de Sales and nuns from the Sisters of the Holy Cross, known for its strict disciplinary regime. This was not a decision likely to build any bridges between father and son.

‘I’d never cracked a Bible in my life and all of a sudden I’ve started studying the Old Testament,’ Dave complained in 2007. ‘It’s like, “Dude, all I did was take acid and spray-paint shit! Why am I here?”’

Bishop Ireton’s ecclesiastical stormtroopers faced a losing battle in trying to convert the school’s newest recruit to the gospel of Christ: by late 1985 Dave Grohl was already in thrall to new gods – British rock legends Led Zeppelin. Dave first heard hard rock’s most powerful band when ‘Stairway to Heaven’ poured out of his mother’s AM radio when he was six or seven years old – ‘Growing up in the seventies,’ Steve Albini once told me, ‘Led Zeppelin were everywhere, so saying you were a fan of Zeppelin was like saying you were a fan of air’ – but it wasn’t until the mid-eighties that the band’s majestic Sturm und Drang became an obsession for him. Every weekend Grohl and Jimmy Swanson would call around to Barrett Jones’s house in Arlington armed with a bag of weed. Together with Jones and his roommate, Age of Consent bassist Reuben Radding, the pair would get high while listening to Zeppelin’s fifth album Houses of the Holy on Jones’s new CD player. In later years, Grohl would claim to have listened so intently to the album that he could hear every squeak of drummer John Bonham’s bass drum pedal.

‘To me, Zeppelin were spiritually inspirational,’ Grohl wrote in a 2004 essay for Rolling Stone. ‘I was going to Catholic school and questioning God, but I believed in Led Zeppelin. I wasn’t really buying into this Christianity thing, but I had faith in Led Zeppelin as a spiritual entity. They showed me that human beings could channel this music somehow and that it was coming from somewhere. It wasn’t coming from a songbook. It wasn’t coming from a producer. It wasn’t coming from an instructor. It was coming from somewhere else.’

To Grohl, Zeppelin were the ultimate rock band, experimental, ambitious, mysterious, dangerous, sexual and dazzlingly adroit, capable of shifting from thunderous blues-rock riffing to gossamer-fine acoustic lullabies at a flick of Jimmy Page’s plectrum. That US music critics largely despised Zeppelin (for all their subsequent sycophantic backtracking, Rolling Stone’s review of the quartet’s self-titled début album, released on 12 January 1969, just two days before Grohl’s birth, dismissed the band’s songs as ‘weak’ and ‘unimaginative’) only enhanced their standing in Grohl’s eyes. To Grohl, guitarist Page, the conductor of Zeppelin’s light and magic, was a ‘genius possessed’ while bassist John Paul Jones was ‘a musical giant’. But it was John Bonham’s masterful drumming which truly blew his mind.

‘Led Zeppelin, and John Bonham’s drumming especially, opened up my ears,’ he told MOJO magazine in 2005. ‘I was into hardcore punk rock; reckless, powerful drumming, a beat that sounded like a shotgun firing in a cement cellar. Houses of the Holy changed everything.

‘As a 17-year-old kid raised playing punk-rock drums, I just fell in love with John Bonham’s playing – his recklessness, his precision. There were times when he sounded to me like a punk-rock drummer. [Led Zeppelin] were so out of control. They were more out of control than a Dead Kennedys record.

‘Bonham played directly from the heart. His drumming was by no means perfect, but when he hit a groove it was so deep it was like a heartbeat. He had this manic sense of cacophony, but he also had the ultimate feel. He could swing, he could get on top, or he could pull back … I learned to play by ear. I wasn’t trained and I can’t read music. What I play comes straight from the soul – and that’s what I hear in John Bonham’s drumming.’

Given his new-found obsession with Zeppelin, it was natural that Jimmy Page’s band would provide a foundation for Grohl’s next musical project. Former Minor Threat man Brian Baker had offered Grohl the chance to play with his new band Dag Nasty, but the drummer was now looking to play something more challenging than four-to-the-floor punk rock: (‘He turned me down,’ recalls Baker, ‘but you have to remember that we were children then, so it wasn’t like he turned me down flat, it was more like, “Oh, that sounds like fun, but I have to practise with these guys and … oh, hold on, Mom, I’m coming …”’) He also wanted to continue playing with bassist Dave Smith, with whom he had developed an almost telepathic understanding. The biggest problem for the pair initially was finding a guitarist who operated on the same wavelength, and could boast the musicianship to match. Both Larry Hinkle and Sohrab Habibion jammed with the pair – by now known to friends by the nicknames Grave (Grohl) and Smave (Smith) – but both guitarists readily concede now that their chops weren’t up to scratch at the time. It was Dave Smith who suggested that the duo might try hooking up with his friend Reuben Radding, as Age of Consent had just recently broken up.

The Georgetown-born son of two classical musicians – his father was a violinist in the National Symphony Orchestra, his mother an opera singer – at 18 Radding had already been a touring musician for three years. Now a well-respected jazz musician based in Brooklyn, New York, Radding – like Grohl – was a childhood Beatles fan and originally a guitarist but had switched to bass when an opportunity arose to join the Gang of Four/PiL/The Jam-influenced Age of Consent. On a personal level, Radding didn’t know Grohl particularly well – ‘To me he was this very goofy but charismatic guy who was at once both shy and extroverted,’ he recalls – but he was well aware of the teenager’s prowess as a drummer.

‘Dave’s reputation as a drummer began spreading from the first time he got behind the drums at a Mission Impossible rehearsal, well before any live gigs,’ he recalls. ‘Dave Smith had been one of my best friends for years, he lived with his parents right up the hill from me on the same tree-lined street, and one day I got a phone call, saying, “Dude, you have got to come up here and check out Dave Grohl playing drums. You won’t believe it. He’s better than Jeff Nelson!” Jeff Nelson was pretty much considered by everybody to be the best hardcore drummer around, so if Dave said that Grohl was better it was something I had to check out … it had to at least be worth a walk up the hill.

‘What I saw was exactly what had been described, and more. Grohl was flat out ridiculous. It was like watching a young Keith Moon, but he was sort of simultaneously being it and being outside it with a surprised look on his face, almost like he was watching it too and didn’t know what was making his hands and feet do these energetic and musical things. He was fun to watch right from the start. Whatever he lacked in metronomic solidity he made up for in raw excitement.

‘Mission Impossible and my band were scene friends. We loved supporting them and they were frequent followers of our shows and tapes. Stylistically we were worlds apart – I loved hardcore but I looked like a flower child or New Waver, more likely to wear paisley shirts and hand-painted sneakers than torn T-shirts and Doc Martens or Vans – but good musicians are into good music, and we shared that nonconformist, open-minded mindset of early punk rock.

‘When Mission Impossible dissolved I didn’t think that Dave and Dave’s next move would possibly involve me,’ Radding admits. ‘Even more than my lack of hardcore cred, I’d become a bass player and whatever reputation I had – not much beyond our Arlington circle, believe me – was as a bass player, an innovative one: switching back to guitar was not something I foresaw myself doing. I still owned one, though, and when Dave Smith asked if I would come do a jam session on guitar I jumped at the chance, not because I thought it was going to be a band, but because those guys were so great I wanted to experience playing with them. I dusted off my long-ignored electric guitar and got in Smave’s van for the ride down to Springfield.’

When I spoke to Radding in 2010, his memories of his first jam session with Grohl some 25 years previously were still remarkably vivid.

‘The Grohl residence was small,’ he recalled. ‘I remember Dave setting the drums up in the living room, and with Smave and I and our amps in front of them the front door to the house was only a couple feet away from my ass. They showed me the first of their “songs” – it was just a riff, really, a little guitar figure, and then the drums and bass came in in a call-and-response pattern: I don’t think I’ll ever forget what it felt like. It was not like playing music with anyone else. Listening to Dave Grohl play the drums had always been a gas, but playing with him was instantly addictive and a total rush. It was like having your ass lifted in the air as if by magic.’

Grohl’s own memories of the session were rather more prosaic: ‘We smoked a whole bunch of pot,’ he recalled, ‘wrote four songs and Dain Bramage was born.’

Led Zeppelin may have provided the common link in Radding, Smith and Grohl’s musical tastes, but their new band incorporated myriad diverse influences: Hüsker Dü, Moving Targets, Television, Mission of Burma, Black Sabbath, Neil Young and Metallica were just a handful of the bands who shaped the Dain Bramage sound. In Foo Fighters’ first press biography, released to the world’s media in 1995, Dave Grohl remembered Dain Bramage as being ‘extremely experimental, usually experimenting with classic rock clichés in a noisy, punk kind of way’. When I interviewed him for a career retrospective cover story for UK music magazine MOJO in 2009, he summed up his experiences in the band in just one sentence, stating, ‘Nobody fucking liked us, because we sounded like Foo Fighters.’

Here Grohl was being somewhat disingenuous. Ian MacKaye remembers Dain Bramage being ‘a little less euphoric than Mission Impossible, and not quite so out of control, but cool’, while some of Grohl’s closest friends, Larry Hinkle and Jimmy Swanson among them, actually rated the three piece as superior to his previous band. The band’s biggest problem was simply that they were in the wrong place at the wrong time: Dain Bramage’s Led Zeppelin-referencing, hard rock-meets-art punk sound would have made perfect sense in Washington state circa 1985 or 1986, but in the capitol of punk, the group stood out like a drum solo at a Ramones concert. Which, to a large extent, was exactly what Radding, Smith and Grohl had intended.

‘We felt like there wasn’t really a model for what we were doing,’ says Radding, ‘and it was both frustrating and a source of pride. I mean, for us it was the fulfilment of a dream to be able to present something we felt was truly our own but it could be pretty lonely at times.’

Mindful of the distance they had placed between their new band and Mission Impossible’s propulsive posi-punk, the trio approached their début gig at the Lake Braddock Community Center on 20 December 1985 with some trepidation.

‘I remember feeling really excited to share what we were working on and I knew our group was special and something different for the hardcore scene,’ says Radding, ‘but I was worried about being accepted since I’d never really been part of that scene. Everyone else seemed to know who everyone was and I had kids coming up to me asking, “Who are you?” I had long hair and was wearing a sweater over a button-down shirt and in that environment I was somewhat of an enigma.’

Dain Bramage opened up their début gig with a song called ‘In the Dark’, a reflective, mid-tempo minor key number. As he sang into a battered SM-58 mic just inches from a sea of curious faces, Radding was convinced that Burke’s young punks hated his band, but as the final notes rang out the assembled crowd broke into cheers and loud applause: ‘I was never so happy or relieved to hear a reaction like that in my life,’ he laughs.

Twenty-five years on, Radding has one other indelible memory of that first Dain Bramage performance.

‘It was the first time as a front man that I ever experienced seeing an entire audience looking over my left shoulder through the whole gig,’ he laughs. ‘I had to get used to that pretty quickly, playing with Dave. I could play all the good guitar I wanted, and sing like a motherfucker, but all eyes were gonna be on Dave all the time. At first I resented it. Then I embraced it. We should have set up like a jazz band with him on the side facing in, then at least I could have watched too. Dave’s charisma was ever-present, both in performance and off stage.

‘He was always kind of hyperactive and he bears the distinction of being the only guy I ever knew who would smoke pot and become more hyper,’ he continues. ‘When he would get stoned he would act truly deranged and go into these episodes of extroverted performance, doing skits and voices, hilarious stuff. I can still remember us laughing till we were in serious pain at some of the stuff he would do when he got stoned. It was kind of like watching Robin Williams at his best – that energy and creative spontaneity – but better than a performance because it was real.

‘At one point he earned a new nickname from Dave Smith. We were at some house partying and Grave had been totally going off. Next thing you know he’s passed out under a pile of clothes in the corner and someone said something like, “Well, he’s finally had it.” And Smave just shook his head. “No,” he cautioned, “he’s just energizing.” Sure enough, Dave was back up at full energy in about twenty minutes and just totally going nuts. So for a little while Dave was known as The Energizer.’

Shortly after their baptism of fire at Lake Braddock, Dain Bramage cut two demos with Barrett Jones. The first featured five tracks – ‘In the Dark’, ‘Cheyenne’, ‘Watching It Bake’, ‘Space Car’ and ‘Bend’ – while the second included a cover of Grand Funk Railroad’s 1973 Billboard chart-topping blue-collar anthem ‘We’re an American Band’, alongside originals such as ‘Home Sweet Nowhere’ and ‘Flannery’. Given Mission Impossible’s previous connection with Dischord it might have made sense for Grohl to approach Ian MacKaye about putting out a record, but the trio were (understandably) concerned that their artful post-hardcore might sound out of step with much of the didactic, righteous rage showcased on the nation’s premier punk rock imprint.

‘Looking back, we had a bunch of incorrect ideas in our heads by that time,’ Radding admits. ‘We were in a period of being down on Ian back then. We made fun of him behind his back. It’s one of the bigger sources of guilt in my recollections of that time, because the main reason we were snotty about him was just that so many people admired him so we felt like we had to tear him down. How fucking childish. I have the utmost respect for Ian and Dischord even though I like relatively little of their music. What he has built over the years is nothing short of extraordinary, and if we’d been a little less young and stupid we might have done more to join forces with Dischord or somebody else who would have carried more weight. What were we thinking?’

Unusually for a DC area band, Dain Bramage ended up signing with a Californian record label, the inelegantly named Fartblossom Records, a new venture for punk rock promoter Bob Durkee (later ‘immortalised’ in scathing, scabrous verse in the song ‘Bob Turkee’ on NOFX’s 1986 EP So What If We’re on Mystic!). Asked what Fartblossom offered that other labels could not, Radding is disarmingly honest: ‘Frankly the appeal was that he asked us,’ he concedes.

In June 1986 the band booked a four-day recording session at RK-1 Recording Studios in Crofton, Maryland with engineers E.L. Copeland and Dan Kozak (formerly the guitarist in Radding’s band Age of Consent) to record their début album. The trio had suffered a falling out with Barrett Jones – ‘They were rehearsing in our house using my PA, and there was some tension about them taking over the house and my equipment without ever really asking,’ Jones recalls – and Radding convinced his bandmates that they needed to use a ‘real’ studio in order to get a bigger and better sound for their début album. Visiting RK-1 for a reconnaissance mission, Radding was somewhat alarmed to discover that this ‘real’ studio was little more than a soundproofed suburban garage, but he swallowed his instincts and said nothing. It was a decision he would come to regret.

The recording did not go smoothly. Within minutes of the band setting up their gear on 21 June, the local police interrupted the session, having been summoned by a noise complaint from Copeland’s elderly college professor neighbour. No sooner had the cops departed than a thunderstorm knocked out all the power in the studio.

‘The power went out in the whole neighbourhood,’ Radding recalls. ‘We took a “break” that went on for hours, all of us sitting on the screened back porch watching and listening to the storm and then finally giving up and packing up a lot of our gear by flashlight. The next day’s dubbing/mixing session turned into an all-nighter. Little things seemed to take forever to accomplish.’

‘It was probably the worst first weekend of recording I’ve ever had in my life,’ Copeland, now the owner of Rock This House Audio and Mastering in Ohio, admitted to me in 2010. ‘But the band were extremely organised and we quickly caught up. There wasn’t a lot of fiddling around or double-takes, it was just boom! We blazed through the songs and it was over. All the guys in that band were really energetic, but Grohl was something special. I thought it was really weird to see somebody beat the living piss out of a drumkit, I’d never seen that kind of playing before. We had a blast, it was a good time.’

Copeland mixed the ten-track album in a day, at which point Radding sent the tape off to his label boss in Pomona. Some months later the group received in the post the test pressings of their first album, a number of songs from which the trio proudly previewed on a Sunday evening show on local ‘alternative’ radio station WHFS. Radding told the show’s presenter that the album, to be titled I Scream Not Coming Down, would be released in a matter of weeks. Back at Kathleen Place later that evening, Grohl listened back proudly to his mother’s cassette recording of the radio interview.

‘I remember thinking that it was so fucking cool that there was a DJ introducing one of our band’s songs, going out to maybe a couple of thousand people,’ he told me in 2002.

‘And that,’ he added with a laugh and a theatrically raised eyebrow, ‘was when I knew that eventually, one day, I’d become the world’s greatest rock star.’

In the weeks that followed the WHFS interview, Grohl was repeatedly stopped by friends enquiring where they could buy his album. On each occasion he promised that the album would be out in a week or two. But when weeks turned into months, with a release date seemingly as distant as the line of the horizon, such questions faded into silence. Morale in the Dain Bramage camp dipped: it was a dispiriting, frustrating time.

Late in the autumn of 1986 Dave Grohl found himself buying new drumsticks in Rolls Music in Falls Church. It was here that he spotted a note pinned among the flyers on the shop’s bulletin board. It read ‘Scream looking for drummer. Call Franz’. At first disbelieving, Grohl re-read the note several times, before tearing it from the board and stuffing it into his pocket. With Dain Bramage in limbo, he figured that he might as well take the opportunity to jam with a band he considered heroes. When he got home, he picked up the phone and dialled the number.