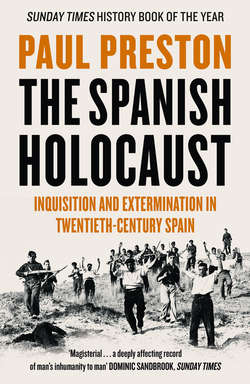

The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Paul Preston. The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain

The Spanish Holocaust

Paul Preston

Copyright

Dedication

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

PROLOGUE

1

Social War Begins, 1931–1933

2

Theorists of Extermination

3

The Right Goes on the Offensive, 1933–1934

4

The Coming of War, 1934–1936

5

Queipo’s Terror: The Purging of the South

6

Mola’s Terror: The Purging of Navarre, Galicia, Castile and León

7

Far from the Front: Repression behind the Republican Lines

8

Revolutionary Terror in Madrid

9

The Column of Death’s March on Madrid

10

A Terrified City Responds: The Massacres of Paracuellos

11

Defending the Republic from the Enemy Within

12

Franco’s Slow War of Annihilation

13

No Reconciliation: Trials, Executions, Prisons

Epilogue

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Photographic Insert

GLOSSARY

NOTES

APPENDIX

SEARCHABLE TERMS

OTHER BOOKS BY PAUL PRESTON

About the Publisher

Отрывок из книги

Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain

Title Page

.....

Unfortunately for the Republican–Socialist coalition, for an increasing number of middle-class Spaniards the excesses of the army and the Civil Guard were justified by the excesses of the CNT. On 18 January 1932, there was an insurrection by miners who took over the town of Fígols in the most northerly part of the province of Barcelona. The movement spread to the entire region of northern Catalonia. The CNT immediately declared a solidarity strike. The only place outside Catalonia where there was any significant response was Seville. There, the CNT, with the backing of the Communist Party, called a general strike on 25 and 26 January. The strike was total for the two days and public services were maintained by the Civil Guard. The accompanying violence convinced the Socialists that there were agents provocateurs in the anarchist movement working to show that the government was incapable of maintaining order. On 21 January, Azaña also declared in the Cortes that the extreme right was manipulating the anarchists. He stated that those who occupied factories, assaulted town halls, uprooted railway tracks, cut telephone lines or attacked the forces of order would be treated as rebels. His response was to send in the army, apply the Law for the Defence of the Republic, suspend the anarchist press and deport the strike leaders from both Catalonia and Seville. Inevitably, CNT hostility against the Republic and the UGT intensified to a virtual war.63

There were other fatal incidents involving the Civil Guard throughout the months following Arnedo. As part of the 1 May 1932 celebrations at the village of Salvaleón in Badajoz, a meeting of FNTT members from other towns and villages in the province was held at a nearby estate. After speeches by several prominent Socialists including the local parliamentary deputies Pedro Rubio Heredia and Nicolás de Pablo, a workers’ choir from the village of Barcarrota sang the ‘Internationale’ and the ‘Marseillaise’. The crowd dispersed, many to attend a dance held in Salvaleón. Afterwards, before returning to Barcarrota, the choir went to sing outside the home of the Socialist Mayor of Salvaleón, Juan Vázquez, known as ‘Tío Juan el de los pollos’ (Uncle John the Chicken Man). This late-night homage infuriated the local commander of the Civil Guard whose men opened fire, killing two men and a woman, as well as wounding several others. In justification of his action, the commander later claimed that a shot had been fired from the crowd. Arrests were made, including the deputy Nicolás de Pablo and Tío Juan, the Mayor of Salvaleón. Pedro Rubio would be murdered in June 1935, Nicolás de Pablo at the end of August 1936 and Juan Vázquez in October 1936 in Llerena.64

.....