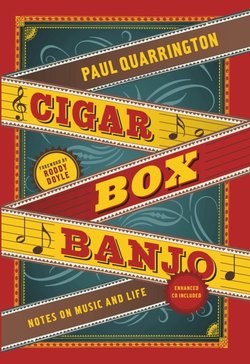

Читать книгу Cigar Box Banjo - Paul Quarrington - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFOREWORD

AS I START to write this I’m listening to an album called You & Me, by a band called the Walkmen. Ten minutes ago, I bought an album called Songs of Shame, by a band called Woods. I did this so I’d have something new on my iPod as I walk to collect my daughter from her choir practice later today. Last night I volunteered to wash the dishes because a) the dishwasher is broken, and b) I could listen to four or five tracks from another recent purchase, the Velvet Underground’s Loaded. Actually, it’s Fully Loaded, which is Loaded with extras, including a demo version of “Satellite of Love,” a song that became famous later in Lou Reed’s career. The final version, the version I first listened to in 1973, is on Reed’s album Transformer. I still remember loving the lines:

I’ve been told that you’ve been bold

With Harry, Mark, and John.

I remember hoping that my parents would—and wouldn’t— charge in from the room next door and demand that I stop playing the record. The record didn’t belong to me. I had it for the night and I was recording it by holding my tape recorder up to one of the stereo speakers. The whole record was a taunt, to me, to my parents, to the world. But they didn’t charge in; they remained untaunted. Nevertheless, I’ve always loved those lines.

The demo on Fully Loaded was recorded in 1970 and the lyrics are slightly, but significantly, different.

I’ve been told that you’ve been bold

With Wynken, Blynken, and Nod.

The “Wynken, Blynken” version was recorded two years before “Harry, Mark, and John” but my reaction, when I heard “Wynken” and “Blynken” last night, was almost violent. What did Reed think he was doing? I know: he’d actually changed the lyrics and saved the day. And I know: it’s only a couple of lines from a song. But, for a few seconds, the time it took to wash one bowl and overcome the urge to smash it, I couldn’t see that. To claim that music is more important than oxygen would be trite and sentimental. But it would also be true.

I love music. I seem to remember a disco song with those words—I love music, any kind of music. I just looked it up; it was the O’Jays. I wouldn’t be as generous as the O’Jays, because I think most music is shite. But I have to admit, if I’d been in the O’Jays—and I wish I had been—I’d have been quite content to sing along. I love music, even shite music. Which is just as well, because I live on an island called Ireland where much of the music is shite. I grew up listening to “Danny Boy”; I grew up hating Danny Boy, and all his siblings and his granny. The pipes, the pipes are caw-haw-haw-hawling. Anything with pipes or fiddles or even—forgive me, Paul—banjos, I detested. Songs of loss, of love or land; songs of flight and emigration, of going across the sea; songs of defiance and rebellion—I vomited on all of them. My own act of rebellion, in a wet land full of rebel songs, was to hate all Irish rebel songs, in fact, all Irish songs, everything that sounded vaguely Irish, including the language and all who spoke it, or even thought in it.

Then I heard Jackie Wilson singing “Danny Boy.” It wasn’t that his rendition was extraordinary, although it is. The song just stopped being Irish. It was being sung—it was being demolished—by Jackie Wilson, a black American who, as far as I knew, had no connection with Ireland, and I could actually listen to the song. It was a liberating, interesting moment. Liberating, because, freed of its time and geography, it became a song that I could like. Interesting, because it made me think about songs in general and what made them good, or bad. “I Say a Little Prayer” is my favourite song, but only if it’s sung by Aretha Franklin. “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” is a dreadful song, but I wish Otis Redding had recorded it. I’d never liked “The Rocky Road to Dublin,” another of the songs I was unable to avoid when I was a child, until I heard and saw it used at the end of a documentary film called Rocky Road to Dublin. The film was made in Dublin, in 1967. The camera is on the back of a lorry as it passes a school, very like the school I went to, just as the school is emptying. The boys, very like the boys I knew and the boy I’d been, spot the camera and run after it. That’s what you see as the Dubliners start to play and Luke Kelly starts to sing, the boys charging after the lorry. It’s an exhilarating end to what is a brilliant, but depressing, film about the misery of life in Ireland in 1967. These boys cheerfully running after the lorry become the country’s future, the children who’ll grow up and rescue the place. And the song, a song about emigration written sometime in the nineteenth century—saluted father dear, kissed my darlin’ mother, drank a pint of beer, my grief and tears to smother—becomes the rhythm of that future. One of the songs I’d taught myself to hate became wonderful—even with the banjo.

Why am I writing all this? (By the way, I’m listening to Grizzly Bear now.) I suppose it’s to suggest that I’m qualified to write the foreword to a book about songs. I’ve never written a song, or a line from a song. I’ve met people who think I wrote the soundtrack to The Commitments and, once or twice, I haven’t put them right. I have to admit, it’s nice being the man who wrote “Mustang Sally.” But I know: I didn’t write “Mustang Sally,” or “Try A Little Tenderness.” I currently have 4,920 songs on my iPod, and I wrote none of them. But I love all of them. I love yapping about songs and their composers and interpreters, probably more than actually listening to them. My books are full of songs. Subtract the song lyrics and one or two of my novels would immediately become short stories. So, I’m qualified.

But that’s not why I was delighted to be asked to write this foreword. I wanted to do it because I wanted Paul Quar-rington to read it.

I have friends I grew up with, and friends I’ve met along the way. Paul Quarrington is one of the latter. If I try, I can calculate the number of times I’ve met him. All I have to do is work out the number of times I’ve visited Toronto, add a trip to Calgary and a few meetings in New York. It might be ten, or nine, or thirteen. But it doesn’t feel like that. I met a friend of Paul’s recently and I assumed, because of the way he spoke about Paul, the obvious affection that was there, that he’d known Paul for years, decades, significant chunks of two centuries. But I found out later that they’d met less than a year before. It didn’t really surprise me. Ten minutes in the company of Paul Quarrington, and you’re instantly an old friend. It feels like that and—I don’t know how—it is like that.

So, I can claim, if only to myself, to be an old friend of Paul’s. And I can claim to be an admirer of his work, because it’s true. I think Whale Music is magnificent. Or, if I had to restrict “magnificent” to just one book, I’d give it to Civilization and declare Whale Music “an inch short of magnificent.”

At this point I stopped writing the foreword.

I went to India, to attend the Jaipur Literature Festival. It took me a day and a half to get there. I had to leave Dublin earlier than I’d planned, to avoid a strike by Dublin’s air traffic controllers. At the other end, the journey from Delhi airport to Jaipur was a seven-hour terror, as the driver slalomed between trucks and camels, off the road, back on the road, around sacred cows and through crowds of people, past rows of elephants, thumping the horn and muttering to himself all the way. When I finally got to the hotel, I slid onto the bed and slept like an unhappy baby, my body on the bed, my head still in the car. But my head eventually stopped, and I slept properly. I woke the next morning, happy to be in India for the first time. I plugged in my laptop and checked my e-mail. There was far more incoming mail than was usual, most of it from friends and acquaintances in Canada, and the subject lines on all of them—Paul, Paul Q, Paul Quarrington—told me that Paul had died. I felt very far from home.

I answered most of the e-mails and texted my wife, Belinda. She phoned later. (There’s a five-and-a-half-hour time difference between Jaipur and Dublin.) By that time I was at the festival, and I cried a bit as I spoke to her. She’d never met Paul but she knew how highly I regarded him. (Writing about Paul in the past tense feels like betrayal.) I always came home from Toronto with new Paul stories; he was always on his way to Dublin.

Belinda never met Paul but it was through her that I met him. She’d worked in a college in Dublin some time in the mid-1980s when a young man from Toronto called Dave Bidini came visiting. They became friends. He stayed a summer, I think, then went back home to Canada—and Ireland breathed a giddy sigh of relief. Years later, he wrote to her, with the news that he was coming to Dublin with his band, the Rheostatics, and that they all loved a book called The Commitments. She wrote back with the news that she was married to the man who wrote The Commitments. So, I met Dave—another instant old friend. He introduced me to Paul.

I cried, a bit, as I spoke to Belinda on my mobile phone, in a quiet corner, perhaps the only quiet corner in Jaipur. I told her how I’d hoped that Paul would read the foreword, that he’d read how much I admired his work and how much I admired him, how much I just plain liked him and loved him. But, even as I spoke, I knew: Paul had always known that. He’d have seen it on my face every time we met. What made me cry was the obvious, stupid fact that we’d never meet again.

I had a great time in Jaipur. I thought about Paul a lot. He’d have loved the cows. On the way back to Delhi, in a fog as thick as old milk, the car I was in nearly—really very fuckin’ nearly—crashed into the back of a stationary truck. In the split second before I died—I was calm, terrified, certain of this—I didn’t think of Paul at all. There were no nice thoughts of the bar in heaven, where Paul would be waiting, with a cold beer for me; or thoughts of the bar in hell, where Paul would be waiting, with a warm beer for me—and a banjo. An eternity of warm beer I could tolerate, even enjoy. But an eternity of the banjo? Even un-strummed, it would be torture, squatting there waiting to be strummed.

But the brakes worked, finally, and I didn’t die. I survived, and so did my atheism. Paul is dead.

But how he died. It’s in this book. A book about music becomes a book about music and death, and Paul manages to make them hold hands. (When considering Paul’s work, I can use the present tense and it feels like honesty.) A hugely enjoyable, very funny book about Paul’s career in music becomes a magnificent book about his death and remains hugely enjoyable and very funny—in fact, funnier. He saw it coming and he took control.

Paul died. But, as this book so brilliantly reveals, and as those of us who are so, so lucky to have known him and to have been known by him understand—in all possible meanings of the word—Paul lived.

RODDY DOYLE