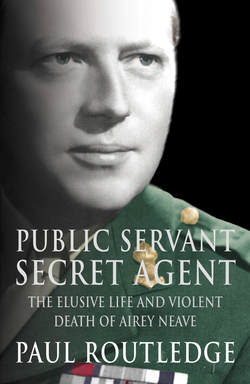

Читать книгу Public Servant, Secret Agent: The elusive life and violent death of Airey Neave - Paul Routledge - Страница 6

2 Origins

ОглавлениеAirey Neave was born at 24 De Vere Gardens, Knightsbridge, a stone’s throw from Kensington Palace and just down the road from the Royal Albert Hall, on 23 January 1916. His father, Sheffield Airey Neave, continued an eccentric family tradition and burdened his son with family surnames, adding to his own that of his wife Dorothy Middleton. Thus, Neave was christened Airey Middleton Sheffield. As he grew up, Airey began to hate his whimsical collection of names, so much so that he rechristened himself Anthony during the war years and only reverted to Airey when he entered public life.

Airey must have quickly appreciated that his family was steeped in history. Of Flemish – Norman origin, the Neaves came to England in the wake of William the Conqueror and settled in Norfolk about 200 years before the earliest recorded member of the family, Robert le Neve, who lived in Tivetshall, Norfolk, in 1399. His forebears lived in villages around Norwich where they became landowners and sheep farmers. As they prospered in the wool trade, some le Neves struck out further afield, to Kent and Scotland, but they stayed chiefly in East Anglia, gaining social distinction. Sir William le Neve, a native of Norfolk, was Clarenceux King-of-Arms at the College of Heralds in London in 1660.

The failure of the wool trade in the mid-seventeenth century drove some enterprising members of the family to seek their fortunes in London, with mixed results. One generation was wiped out by the Black Death in the 1660s (the victims are reputedly buried under a church in Threadneedle Street) but Richard Neave, who lived from 1666 to 1741, fared better, establishing a prosperous business in London, with offices in the Minories. He made most of his wealth from the manufacture of soap, a new and very fashionable product for the period. He bought land east of London outside the city limits, where his sons began to establish what would become London docks. His business also expanded overseas, with estates in the West Indies, and he put his accumulated resources into his own bank in the City.

The business further prospered through judicious marriages and Richard’s grandson, bearing the same name, bought the Dagnam estate in Essex, so beginning the family’s long connection with the county which remains to this day. His grandson became Governor of the Bank of England in 1780 and a baronet in 1795. The family crest, a French fleur-de-lis, with a single lily growing out of a crown, long predates the adoption of the Neave motto, Sola Proba Quae Honesta, which translates literally as ‘Right Things Only Are Honourable’. Speculation about possible royal connections linked to the appearance of a crown on the crest, admits Airey’s cousin Julius Neave, has given rise to ‘some fanciful but quite unsubstantiated theories’ as to the family’s origins.

However, the family’s upward mobility was undeniable. Sheffield Neave, another Governor of the Bank of England (1857–9), gave his Christian name to succeeding generations (some noted for their longevity), one of whom was Airey’s grandfather, Sheffield Henry Morier Neave (1853–1936), well-known in Essex for his eccentricity. He inherited a fortune while still at Eton, and went up to Balliol College, Oxford, where he acquired a degree but showed no inclination to pursue a profession thereafter. With plenty of money and no need to work, he indulged his passion for big game hunting, spending long periods in Africa, where he became convinced that control of the malarial tsetse fly was the only bar to great agricultural prosperity in sub-Saharan Africa. He returned to England and studied to become a doctor in middle age, eventually rising to become Physician of The Queen’s Hospital.

At the age of twenty-five, Sheffield Neave married Gertrude Charlotte, daughter of Julius Talbot Airey. They lived at Mill Green Park, Ingatestone, which was to become the family seat, and it was to Mill Green that Neave would return after his incarceration in Colditz. He dreamed vividly of the house during his captivity, and lyrically described its chestnut trees, its May blossom and the white entrance gates in his first book, They Have Their Exits.

Sheffield Neave had his own Essex stag hounds and was a legend in the field. Ever the eccentric, the stags he hunted were not wild but carted to the meet in the same vehicle as the hounds: ‘There was never any question of the hounds killing the stag, who was much too valuable to be lost in this way,’ Julius Neave has explained.1 ‘They all came home to Mill Green at the end of the day and were stabled together.’ Sheffield gave up stag-hunting at the turn of the nineteenth century, complaining that ‘Essex is getting too built over’, but he rode to hounds until nearly eighty, when he took up golf instead. Long after his death a particularly vicious jump over a ditch and stream was still known as ‘Neave’s leap’.

Gertrude Neave, the epitome of a Victorian lady, was an accomplished pianist and also composed music. She came from a distinguished family, one of her relations being General Lord Airey, chief of staff to Lord Raglan, Commander-in-Chief of the British army in the Crimean War. He was, reputedly, the ‘someone who blundered’ over confused orders which led to the Charge of the Light Brigade. Gertrude and Sheffield had two sons and two daughters. The elder son, Sheffield Airey, born in 1879, was Airey Neave’s father; the younger, Richard, became a professional soldier and saw service in the Boer War, India and in Gallipoli in 1916. He also served in Ireland during the Troubles of 1920–22, and Airey may well have heard stories of ‘the Fenians’ from his uncle.

Airey’s father went to prep school in Churchstoke, in the Welsh Marches, and then (as befits the grandson of a Governor of the Bank of England) on to Eton and Magdalen College, Oxford, to read natural sciences. He inherited his father’s fascination with Africa and the diseases spread by insects. In the years before the Great War, he travelled in 1904–5 on the Naturalist Geodetic Survey of Northern Rhodesia, and to Katanga as entomologist to the Sleeping Sickness Commission of 1906–8. On his return from Africa, he served in a similar capacity on the Entomological Research Committee for four years before being appointed Assistant Director of the Imperial Institute of Entomology at the age of only thirty-four. He was to hold the post for thirty-three more years and then took over as director in 1942, the year Airey escaped from Colditz, before retiring in 1946.

A big, dominant man with a moustache, Sheffield Neave was a distant figure, immersed in his scientific work and given to a Victorian aloofness from his children. After Airey’s birth, the family moved to a house in High Street, Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, where four more children were born: Averil, Rosamund and Viola, and then a second son, Digby. Dorothy Neave, descended from an Anglo-Irish family, played a traditional role in the family: she ran a comfortable if unostentatious household. There were servants and appearances to keep up but Dorothy was often unwell and died of cancer in 1943 when Airey was working for MI9. Airey’s daughter Marigold says that he did not have a good relationship with his father. ‘He was very much a scientist. Perhaps that is what made him not very easy to get on with. He was very remote, a very Victorian figure.’2 If not physically robust, Airey’s mother possessed a mental determination unusual in her position. ‘Grandmother was quite forward-looking, quite progressive for those days. She was a liberal with a small “l”,’ recorded Marigold. ‘His childhood was not very easy. His mother was very often ill. Officially, he looks very much like her, but he never talked about her. He talked about his father, but not in very glowing terms. He was a very strict character, powerful and good-looking: a strong face, very dark eyes. And physically he was very tough. It was a clash of personalities.’ Group Captain Leonard Cheshire, the Dam Busters war hero, friend and contemporary at Merton, would come to a similar conclusion. Neave, he wrote, was highly independent and always ready to follow his inner convictions. ‘No matter what the opposition, he would often do things that were a little wild, though always in rather a nice way and never unkindly.’ This trait endeared him to school and university friends, ‘but possibly had a different effect upon his father who one has the impression did not always give him the encouragement which inwardly he needed. Thus, at a very early age he learned to conceal his inner disappointments.’3

Airey Neave attended the Montessori School in Beaconsfield, a progressive school where his individuality was respected. In 1925, at the age of nine, he was sent to St Ronan’s Preparatory School in Worthing, Sussex. The headmaster, Stanley Harris, was a remarkable man who had played football for England, and captained the Corinthians, the famous amateur team. The essence of his educational philosophy was captured in the school prayer, known as Harry’s Prayer, which ran:

If perchance this school may be A happier place because of me Stronger for the strength I bring Brighter for the songs I sing Purer for the path I tread Wiser for the light I shed Then I can leave without a sigh For in any event have I been I.

Set in several acres on the outskirts of Worthing, St Ronan’s placed great emphasis on academic excellence, sport and self-development. In many ways an archetypal English prep school – numbering future air vice-marshals and an Asquith among its pupils – it was built in red brick and sat against the backdrop of the South Downs. Despite the usual rigours of such places, the school had a patriotic rather than militaristic air about it. There was no cadet corps but boys were taught shooting, and from time to time a former army sergeant – so old that he had been with Kitchener at Khartoum – came to the school to teach gymnastics and boxing. With their days filled, in the evenings boys were allowed to pursue their own interests. In Neave’s time, some of them built a primitive radio – a crystal set with ‘cat’s whiskers’ tuning. Others drew maps of imaginary countries, bestowing such nations with complex railway timetables. Essentially, they had to learn to make their own amusement, and learn to fend for themselves, all of which helped develop a form of independence.

In 1926 Stanley Harris died of cancer and his place was taken by his brother, Walter Bruce (Dick) Harris, then a housemaster at nearby Lancing College. If Airey was a better than average pupil he was not spectacularly so, and seems to have been suited to his first form which was ‘composed mostly of boys with plenty of ability, one or two of whom however have no great idea of work’. In 1925, he won a combined subjects prize, but in class 1A in 1927 he was fourteenth. By the following year he had crept up to eleventh, then ninth and finally sixth, with 1, 205 points. That autumn, he also won the Latin prize. The highest placing he received was third, but mostly he fluctuated around the lower end of the top ten. The boys were expected to take a full part in the life of the school. Airey played a waiter in the school play in 1928, and the St Ronan’s magazine observed: ‘A word must be given to Neave who by progressive stages became the perfect waiter.’ Praise indeed.

One contemporary at St Ronan’s recalls that Neave was a rather undistinguished small boy, neither games player nor leader nor scholar. He was teased mercilessly about his name. Others spoke warmly of him. Dick Harris described him as having been ‘a gentle child’; echoing that sentiment, Lord Thorneycroft, a contemporary in parliament, would much later describe him as ‘a very brave and yet gentle man’. His daughter Marigold insists that he hated prep school.

At the age of twelve, Airey went to his father’s old school, Eton, one of three boys to go from St Ronan’s in the Lent term of 1929. Eton’s long-serving head, the Reverend Cyril Alington, retired later the same year and his place was taken by Claude Aurelius Elliott, a Fellow and Senior Tutor of Jesus College, Cambridge. Unlike at St Ronan’s, at Eton the house system was everything. Neave’s house tutor was John Foster Crace, a classics teacher who had been there since 1901 but had only become a housemaster in 1923. He was ‘a reticent, reserved and inhibited bachelor with a reputation of being overfond of some of the boys’.4 However, he was a good teacher and ventured out of his reserve to produce Shakespeare on the school stage.

At Eton the emphasis was not just on academic brilliance but on sport and other ‘gentleman’s pursuits’ such as fencing and shooting. Scouting was also encouraged, including quasi-military activities such as signalling. As they grew older, boys joined the Officers’ Training Corps. Eton boys shot at Bisley, beating teams from the Scots Guards and the Grenadier Guards. The school was also a forcing house for politicians. In June 1929, a month after the General Election that brought Ramsay MacDonald into power at the head of an all-Labour Cabinet, the Eton College Chronicle recorded that seventy-six Old Etonians sat at Westminster, more than sixty of them as MPs. Predictably enough, only four of the MPs were Labour, while two were Liberal. Three Old Etonians were ministers in the MacDonald administration, including a young Hugh Dalton making his mark as Parliamentary Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office.

Public figures of the highest rank, including the King and international figures such as Mahatma Gandhi, paid regular visits to Eton. The atmosphere was unashamedly elitist. In Neave’s first year a particularly aggressive Etonian defined the expressive word ‘oick’ as ‘anybody who hasn’t been to Eton’. But when the school debating society considered whether ‘This House would welcome the resignation of the Government’, it was roundly defeated by forty-two votes to twenty, suggesting, perhaps, that the boys were more radical than their forebears.

The St Ronan’s magazine recorded that Airey ‘took remove at Eton, which is the highest form that a new boy who is not a scholar can go into’, and throughout his five years at the school he was competent rather than brilliant. He usually finished among the top half-dozen in his class and on one occasion won a book prize for academic effort, having, as Eton had it, been ‘sent up for good’ three times in a single term. Although the records suggest that he was a good runner, he did not shine at the school’s other traditional sports: cricket, racquets, fencing, soccer, rugby and rowing.

It might be thought that the momentous events away from the playing fields of Eton – the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression of the 1930s – would have passed him by. Indeed, the Eton College Chronicle of October 1930 suggested that the school was ‘terrifyingly remote from the ordinary concerns of life’, yet the same edition carried a spoof on a Communist takeover of the school, with references to ‘Herr Hitler’, and Old Etonians active in the higher reaches of politics would often return to talk to the school. In 1931, the fall of the Labour government amid economic collapse and the return of a national government under MacDonald greatly increased the number of Old Etonians at Westminster to 102, five of them in the Cabinet and nine more scattered in more junior ministerial jobs. It really did seem that being able to say one was an OE was a passport to power. Much has been said about the characteristics of an Old Etonian. A young OE might be considered arrogant, self-conscious, conceited, overconfident; the more mature species had become sober, active and intelligent, a leader of men; while in his dotage an OE might revert to arrogance and jingoism, but of a gentler kind. Neave was too reserved to fit the classic OE profile, but there was something of all those descriptions in him.

Before Neave left Eton he had an experience that few seventeen-year-old English boys of the period could expect to undergo. In September 1933 his parents sent him to Germany to brush up on the language. He was billeted with a family living in Nikolassee, west of Berlin, where he attended school with a boy of similar age who was a member of the Hitler Jugend. Adolf Hitler had become Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933, when President von Hindenburg asked him to form a government as the leader of the largest single party, the National Socialists. Public and political opinion in Britain was slow to catch up with the terrifying prospect opening up in Continental Europe. Winston Churchill expressed admiration for ‘men who stood up for their country after defeat’. The Times asked sympathetically whether the street-orator would be an efficient ruler and the demagogue a statesman. They had their answer within weeks, when the Reichstag, the parliamentary building, was destroyed by fire. New decrees gave Hitler’s private army, the SA (Stürmabteilung), the power to gaol Jews and dissidents without trial. The first concentration camp opened at Dachau and by July of that year German citizenship was allowed only to members of the Nazi Party. Forced sterilisation of ‘inferior’ Germans was ordered. The terror had begun, but many in Britain believed that war could be averted through the League of Nations. Hitler withdrew from the League, yet still Germany remained a favourite holiday destination and Nazism even found admirers at home, particularly in the upper reaches of British society.

As a foreigner, Airey was excused from giving the Nazi salute when the teacher came into his class, but he was made to sit at the back, where he cut a bizarre figure in a ‘decadent’ yellow (Eton) tie with black spots and longer hair than his classmates. He felt something approaching contempt for the growing nazification of the school. Dietrich, the elder brother of the boy with whom he attended school, was impressed by Airey’s air of independence but warned that it was dangerous. On a railway platform at Nikolassee, Airey sniggered at a fat, brown-booted Nazi SA man. Years later, he recollected ‘the bloodshot pig-eyes of the stormtrooper glaring towards us’. Dietrich hastily manoeuvred him out of sight.

Dietrich was not a party member but he did belong to a sports club in nearby Charlottenburg. Airey joined as an honorary member. With his indifferent performances at school in mind, he volunteered for the relay race. A Festival of Sport was declared in September and his club was ‘advised’ by the authorities to field a team. At this relatively early stage of the Nazi takeover, Hitler had not stolen all sporting events as his own and marching in the torchlight procession was regarded as light-hearted and theatrical. Airey’s friend took him on the march in the face of official disapproval. He was dressed in ‘civvies’ and treated the occasion as something of a joke. His fellow marchers, however, did not: ‘As we joined the uniformed Nazis with their band, our mood changed,’ he recorded.5 ‘I felt as if I was being drawn into a vortex.’ The march began at ten in the evening. Neave was in the centre, alongside Dietrich and directly behind a contingent of SA troopers in brown shirts and swastika armbands. Down each side of the procession, burning torches blazed. Initially, Neave admitted, he found the grandiose event thrilling. Crowds watched, their faces shining with excitement and pride.

Sportsmen who had been joking began singing; the mood became religious and the marchers expectant. On their parade from Lustgarten down Berlin’s Unter den Linden, they passed the Royal Palace of Kaiser Wilhelm I and the Ministry of the Interior, home of Hermann Goering’s newly established Gestapo. When Neave broke step with his fellow marchers, Dietrich rounded on him, but it happened again before they reached their festival site, the Brandenburg Gate. ‘I found it difficult to keep in step,’ he admitted. ‘Something subconscious was drawing me away.’6 The gate was floodlit and festooned with Nazi flags, resembling, he recalled, some gateway to Valhalla. As they marched towards the burned out ruins of the Reichstag, bands played the Horst Wessel song (the Nazi anthem) and Neave was caught up in the emotional turmoil that prompted cynical and doubting fellow marchers alike to give the Nazi salute. ‘Some were on the verge of tears,’ he said. ‘Afterwards, I realised that they were lost forever to the Revolution of Destruction, whereas I would escape.’7

Massed bands prepared them for a half-hour speech by Reichssportkommissar von Tschammer und Osten. Airey, the product of a civilisation at odds with the hysteria of Fascism, was bored. The speech was tedious and hackneyed, ‘a maddening anticlimax’. While he fretted, all around him the young intelligentsia listened to the brown-shirted thug with rapt attention, breaking into ‘Deutschland über Alles’ when the speech was over. Neave’s reportage of these events has something of ex post facto reasoning about it. A British teenager, even one educated at Eton, pitchforked for the first time into a foreign country undergoing such convulsions, is unlikely to have come to such sophisticated conclusions. Recollecting these events twenty years later, Neave invested himself with a remarkably mature social and political intelligence, all of which certainly made for a better story. Had his liberal-minded mother known about the reality of Nazism, Airey mused, she would have recalled him instantly. Looking back, he realised that Hitler was preparing the young people of Germany for a war that he had always intended. His youthful eyes had been opened to the dangerous neurosis sweeping Germany but it would be seven more years before he was swept into the net of depravity. He returned to school for the remainder of his final year, to a Britain more perturbed about the controversial MCC bodyline tour of Australia than events in Berlin.

Eton in late 1933 must have seemed an anticlimax after the convulsions he had witnessed in Berlin. His school record shows flashes of distinction rather than consistency. After Eton, an orthodox journey through Oxford – he had chosen to go to Merton rather than follow his father to Magdalen – into the law seemed to beckon. Of good academic repute built initially on the classics, the Merton to which Neave went in the autumn of 1934 was still steeped in Victorian tradition. As the age of adulthood remained at twenty-one, the college stood in loco parentis to its undergraduates and took its responsibilities seriously. Discipline was officially strict, though the authorities turned a blind eye to certain misdemeanours. For the first year students lived in. They had agreeable but austere rooms. There were very few bathrooms: each set had a chamberpot, emptied by the college scout who acted as valet and housekeeper. A normal academic day began at 7.30 a.m. when the scout brought hot water for washing and shaving, and undergraduates then had to attend a roll-call at 8.00, ‘properly dressed’ in socks as well as gowns over their normal clothing. They signed their names in a register in a lecture room in Fellows’ Quad, under the watchful gaze of the day’s duty don. Attendance at matins in the college chapel was an acceptable alternative to roll-call.

After a day of lectures and tutorials, they were free for the evening. Drinking in Oxford’s pubs was forbidden and the rules were enforced by bowler-hatted ‘bulldogs’ (university proctors’ assistants) who toured the watering holes accosting suspects. College gates were closed at 9.00 p.m., and after that students had to ‘knock up’ the porter in his turreted fifteenth-century gatehouse to gain admission. They were fined sixpence after 10.30, and a shilling after ii .00. If an undergraduate had permission to stay out after midnight – rarely granted – he paid a fine of half a crown.

This was all quite expensive for the mid-thirties, when a young man at Oxford could live comfortably on £250 a year, so the curfew was regularly breached by climbing over the perimeter wall back into college. Indeed, it was one of Merton’s traditional sports. Reputedly, twenty-eight break-in routes existed, the most popular being over the wall in Merton Street into the college gardens and then through the loosened bars of a ground-floor set of rooms, where it was customary to leave small change on the table of the hapless undergraduate who occupied the rooms. Dons discreetly allowed the bars to remain loose.

Neave was undoubtedly one of the climbers, an unconscious rehearsal of his exploits at Colditz a few years later, and in captivity he must have mused on the irony of his position, where, for three years, he had perfected the art of breaking in rather than out. Once at Oxford, Neave quickly made his way to the worst company that Merton offered. He was elected to the exclusive Myrmidon Club, a group of undergraduates, never more than a dozen in number, who dedicated themselves to the good things of life. The club was founded in 1865, fancifully in emulation of George Bathmiteff, a Russian nobleman and Merton undergraduate who had dallied with a danseuse who wore a garter of purple and gold. Originally, its aims were to explore the Cherwell and other river systems, but with the advent of undergraduates like Lord Randolph Churchill in the 1870s the club soon became the haunt of young bloods. To perpetuate the memory of the danseuse, Myrmidons, named after the faithful followers of Achilles, wore purple dinner jackets faced with silver and white waistcoats edged with purple and gold. Their chief activities were eating and drinking, generally in each other’s rooms but also formally every term in their own dining rooms above a tailor’s shop in the High Street.

Within months of going up to Merton, Neave was inducted into the Myrmidons, at a meeting in the rooms of K.A. Merritt, a keen tennis player. Colin Sleeman, who was to become Captain of Boats and subsequently a distinguished lawyer and defence counsel at the Far East War Crimes Tribunal, was elected the same day. At that point the club numbered seven. They met regularly in Neave’s rooms for the following year, and in June 1936 he was elected secretary. The minutes show him to have been a conscientious but terse recorder of events. On 20 October 1936, the Myrmidons met in Mr Logie’s rooms, he wrote in a flowing (indeed, overflowing) Roman hand, and fixed the dates for lunch and dinner that term. It must have been a good meeting. Neave’s account, in a trembling hand, is full of crossings-out and emendations. He signed himself with a flourish and then underneath wrote ‘trouble’, without further explanation. On 5 February 1937, he recorded that the Myrmidons met in Mr Wells’s rooms and elected two new members. They organised lunch ‘for a date now lost in the mists of obscurity’, or perhaps the mists of Dom Perignon. The club now had nine members, and was ‘full’. The minute books are the only formal history of the Myrmidons’ activities, though they are still a legend for drinking and bad behaviour at Merton. Some idea of their academic application may be gained from the degrees posted in the college register. One got a fourth in geography, another a pass degree in mathematics; Merritt gained a third in history while Sleeman managed only a fourth in jurisprudence. The Myrmidons were capable of sottishness but were no more than undergraduate drunks. They invited Old Boys to their dinner, invariably held in London, where Neave had become a member of the Junior Carlton Club. They also aimed high in their guest invitations. As late as 1951, Winston Churchill, recently reinstalled as Prime Minister, wrote regretting that he could not attend their dinner because the pressure of affairs was ‘considerable’.

The Myrmidons also gained an eccentric reputation for literary interests, chiefly through Max Beerbohm and his friends who had been members in the 1890s. The Myrmidons are assumed to be the model for the Junta in Beerbohm’s gentle, witty Oxford novel Zuleika Dobson. In spite of being known as the ‘most virile’ of Merton’s clubs, they also had a cultured side, which showed itself most strongly in amateur dramatics. The Myrmidons scorned OUDS – the self-esteeming Oxford University Dramatic Society – in favour of Merton Floats, the college’s own theatre group, founded in 1929 by two undergraduates, Giles Playfair and E.K. Willing-Denton, the latter a ‘prodigiously extravagant and generous’ young man. This was, Playfair later recollected, a time of festive teas, luncheons, dinners, suppers and moonlight trips on the river followed by climbing over the wall into college. Willing-Denton, who spent his entire allowance in the first month, was noted for his ten-course luncheons. He and Playfair persuaded actors of the calibre of Hermione Baddeley to come down to Oxford, and Merton Floats enjoyed a succès d’estime in the mid-war years when the social scene was at its height. In 1936, Neave was secretary of Floats and his friend Merritt was president. Sleeman was the grandly titled front-of-house manager. They put on two plays: In The Zone, a one-act play by Eugene O’Neill set on the fo’c’sle of a British tramp steamer in 1915, in which Neave played the role of Smitty; and Savonarola, a play of the 1890s attributed to Ladbroke Brown, in which Neave appeared as Pope Julius II. Neave also found time to make three speeches at the Oxford Union, of which no record remains. On one of these occasions he found himself debating the merits of the previous week’s motion.

It was an altogether engaging life. Neave later admitted that he did little academic work at Oxford and was obliged to work feverishly at the law before his finals in order to get a degree. He graduated in 1938 with a third in jurisprudence and a BA. ‘The climax of my “Oxford” education was a champagne party on top of my college tower when empty bottles came raining down to the grave peril of those below,’ he wrote.8 He remained thankful in adult life for the kindness and forbearance shown by his college during those profligate years. Life was never to be so insouciant again.