Читать книгу Help Wanted: Wednesdays Only - Peggy Dymond Leavey - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 2

ОглавлениеIt was Easter weekend when Mom and I moved our stuff across the city to Grandpa’s. On Sunday, Jason and his mother brought over some of the smaller boxes from our place and Jason stayed on to visit. Together, we checked out the neighbourhood. It wasn’t something you could do on your own. People would stare at a kid walking up and down the street by himself. This wasn’t a new neighbourhood to me, but I was looking at it now as someone who was going to have to live here.

Back at home, Travis and Nicole were making a working model of a volcano for their science project. They’d probably win. They deserved to; they’d worked together on it every night for two weeks. I guess Nicole wasn’t going to miss me after all. I never did anything to let her know I’d hoped she’d be my girlfriend.

I knew a lot of Grandpa’s older neighbours already. More than once someone stopped Jason and me on the street. “Hey, kid. How’s Luigi doing?” they wanted to know.

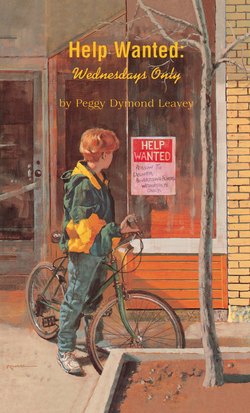

The shops on what passed for the main street in this part of the city were small and run down. Today, if it wasn’t a video store or a donut shop, it was probably closed, the inside of the windows covered with brown paper, the battered doors plastered with posters which advertised some wrestling match coming to the local arena, as soon as the ice came out.

The shop where Grandpa had sold fruit and vegetables now sold yogurt and something called tofu.

“What’s that?” asked Jason, making a face.

“Search me,” I said.

A man in a white uniform was changing the letters on an advertisement board in the window. Behind him, we could see baskets of trailing plants hanging from the ceiling. The walls were painted pastel shades of pink and green. The place gleamed with stainless steel and glass.

But the store next to Grandpa’s had the same pieces of dusty leather luggage in the window that had been there as long as I could remember. The shop on the other side still sold long lengths of blood red sausage.

We drove Jason home when we took back the truck we’d rented to move our stuff. On the way, Mom took us by the school I’d be going to. I wished she hadn’t.

The building was ancient, with classrooms on two floors and a schoolyard made of pavement.

“It looks like one of those correctional institutions,” observed Jason, adjusting his glasses up onto his nose.

“How would you know? You ever seen one?”

“Well, no. But it looks the way I figure one’d look. You know.”

“It looks the same as it did when I went to school there,” said Mom. She’s nearly 40, so you know how old the school had to be. “I’ll bet it’s still got those old wooden floors that creak.”

It had and they did.

The first day, as I climbed up and down the stairs from one Grade Eight classroom to another, I started to appreciate the modern school I’d left behind—all on one floor, with skylights in the halls and grass beyond the cement in the schoolyard.

At first, the kids in the class pretty much ignored me, which was okay by me. I couldn’t see any of them being my friends anyhow. The homeroom teacher, a Mr. Hoskins, who had the thickest pair of glasses I’d ever seen, picked this kid named Nicholas to take me to the office to register. Probably because we were both wearing the identical sweatshirt.

“You like Giant Squid, too?” I asked, referring to the rock group pictured on Nicholas’ chest.

“Naw. This shirt belongs to my brother,” said Nicholas. “He’s pretty uncool.”

His only other bit of conversation, as we went down to the main floor office, was to advise me to stay out of Randy Smits’ way. I’d already spotted the class troublemaker, a big kid with muscles and blonde hair that fell on one side into his eye. He sat in the back of the class with his feet stuck out into the aisle, talking in a soft voice all the while the teacher was. By the way Mr. Hoskins ignored him, just glaring at anyone who reacted to Randy’s comments, it was obvious he’d given up on trying to get his co-operation.

While Nicholas went back up to class, I stayed to pick up papers for Mom to fill out and was assigned a locker. By the time I beat it back up the stairs to the next class, I was one of the last ones to enter the room.

I stood for a moment waiting for Randy and another kid who were ahead of me to go in. But Randy wasn’t in any hurry. He stood in the doorway with his arm draped across the shoulder of his friend, blocking my way.

“If you don’t mind . . .” I began, seeing the others inside, already at their desks. Showing up late in front of a roomful of strangers is not my idea of a good time.

“I do mind,” said Randy. “So you just wait your turn.”

“Yeah. You just wait your turn, dude,” the other kid echoed.

“Are you boys coming to this class or not?” the teacher asked. And while the other two sauntered to their seats at the back of the room, I had to stand and go once more through the rigmarole of who I was and what school I’d come from.

Ms. Rabinski was the environmental studies teacher. She was very tiny and very blonde.

“Oh, Vincent Massey School,” Ms. Rabinski said, raising her delicate eyebrows. “The French programme there is excellent, I hear. You’ll be able to show these Grade Eights a thing or two.”

I heard Randy snort and felt my face getting hot. “Not really,” I mumbled. “It wasn’t my best subject.”

“Oh? And what was?” Was she going to make me stand there all day? Couldn’t she just tell me where she wanted me to sit?

“Recess, right?” Nicholas offered, and everyone laughed. At least it broke the tension. Someone took a bunch of papers off a desk and found me a chair to go with it.

It was just my luck, when noon hour came and I went to drop off my books and pick up my lunch, that I discovered my locker was right next to Randy’s. He and his friend were lounging against the opposite wall. Not waiting for me, I hoped. There are times when I wish I were invisible, and this was one of those times.

“Smart kid, eh? Where’d you come from, smart kid?” Randy came across the hall to where I was hastily shoving books onto the metal shelf over my head.

“Riverview,” I said. “And I’m no ‘A’ student.”

“Riverview. Where’s that?”

“About five miles. Other side of the city.”

“So why’d you come here? Old man take off?”

“We came here to live with my grandfather. He’s sick and needs us.”

“Anyone who’d need you would have to be sick. So where is your old man?”

“He doesn’t live with us. I live with my mother.” Not that it’s any of your business, I wanted to say.

“That’s not the question, dude. I said, where’s your old man.”

“Same place as yours, Randy,” crowed his pal. “He goes to see him twice a month on visiting day!” And he gave Randy a punch on the shoulder that he wasn’t expecting which sent him flying into me. Both of us slammed against the open door of my locker with a crash.

“Hey! Watch it, Joey!” Randy grabbed up his lunch bag off the floor and took off down the hall after his friend.

There was no place else to go and eat except the lunchroom. By the time I got there everyone was already inside. It was packed. I’d rather skip lunch than ask anyone to make room for me. I was just pushing against the door to leave again, as quietly as possible, when someone called, “Hey, Mark. Over here.”

Nicholas was at one of the tables. He swept the plastic wrap piled with sandwiches along the table with his arm and moved down the bench, so I could get my legs in. Saved again. Nicholas might never become my favorite person, but anyone who rescues me from an awkward moment is a friend of mine.

“So,” he said, breathing tuna fish, “How d’you like old St. Laurent Junior High?”

“Okay, I guess. School’s school.”

“You’re right there,” he said. “It sucks in any language. Randy giving you a hard time?”

“Naw. He tried to. I’m used to guys like him.”

“I bet,” said Nicholas, giving me a knowing elbow. “Big guy like you, eh?”

I hadn’t yet had what Mom referred to as my growth spurt yet. That would happen in high school, she predicted. But then, neither had Nicholas.

“Just don’t get in Randy’s way,” advised a girl with pink, spiked hair, who sat on the other side of the table.

My mother had written my name on the brown paper bag that held my lunch. “Mark Rogers,” read a kid on the other side of me. “That your name?”

The girl across the table got up to leave. “Unless he’s eating someone else’s lunch,” she said.

“This is Dennis,” said Nicholas, introducing us. “The one with the mouth is Rhonda. You want to shoot a few baskets? If we hurry, we can still get one of the balls.”

By the end of the first week, I knew plenty of kids. Nicholas was Nick to everyone and Rhonda was much better than her hair. Maybe it wasn’t going to be too bad. It turned out that Mom had gone to school with Mr. Hoskins. She met him when she took the papers back to the office at St. Laurent.

At home, things with Grandpa were about the same, although he seemed to have stopped his wandering away. The doctor had suggested that a short walk every day with Mrs. Fuller or one of us might prevent the wandering. The daily walk seemed to be working.

He didn’t sleep well at night though, and Mom and I often heard him up after we had gone to bed.