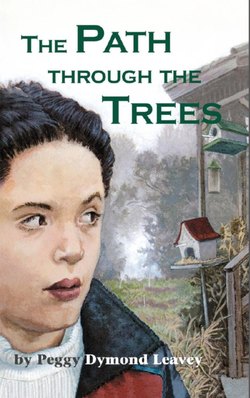

Читать книгу The Path Through the Trees - Peggy Dymond Leavey - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

One

ОглавлениеJody didn’t know what had called him to return. A feeling deep inside him, something like longing, had drawn him back to the little shed in the woods.

He had to use the side of his shoe to scrape all the mud and leaves from the doorway, before finally pushing open the door. In the pale light of mid-December, he saw that everything was as he’d left it—the coal oil lantern that hung from a nail over the workbench, the trusty little woodstove, its pipe thrust up through the roof. The box with the rope handles still held his tools. Even the narrow cot under the window looked undisturbed. It was only when he shook out the blanket covering the cot that he discovered it had been home to a family of mice.

Never mind, he thought. He’d take the pipes down and bang the soot out of them. Then he’d get a fire going in the little stove. It had always been sufficient to heat this small space. He’d have it cozy in no time. Even the field mice were welcome to stay, provided they found a corner of their own and left the cot for him.

Jody had been down to the big house only once since his return, and he hadn’t seen the lady there. He’d go down again later and have another look around. He wondered if she might be sick. Could that be the reason he’d been summoned to return?

He picked up the straw broom that stood in the corner and busied himself sweeping the floor. Through the sound of the rain pattering on the carpet of leaves outside came the whistle of the train as it approached the level crossing. Jody lifted his head and listened.

Norah Bingham stood alone on the station platform. The throbbing of the train, now disappearing into the distance, filled her head. She had the sensation that her body still rocked from side to side with its rhythm.

A single yellow taxi waited in the rain. Where, she wondered, was Great-aunt Caroline?

The driver got out of the cab and watched as she approached—a thin girl, wearing jeans and a hip-length navy jacket. She was dragging a nylon suitcase on wobbly wheels and skirting the puddles.

“A girl, the lady told me,” the man acknowledged, giving a hitch to his jeans. “And seeing’s you’re the only one who got off, you must be her.” He reached out for the suitcase.

Norah hesitated, peeling a damp strand of wind-blown hair from across her mouth. “I understood Miss Caroline Stoppard was to meet me.”

“Well, you understood wrong,” the man grunted. He seized the suitcase and slung it onto the back seat of the cab. “Miz Stoppard paid me to fetch you, and that’s what I’m doing. So get in, please. No sense standing out here getting wet.”

Seeing as her luggage was going wherever the yellow taxi was, Norah had no choice but to climb into the cab beside the suitcase. The driver closed her door and slid in again under the wheel. “Don’t know how you figured Miz Stoppard could come and fetch you,” he muttered, adjusting the mirror so that Norah could see his eyes. “She hasn’t had that car of hers out of the garage in years.”

The cab jolted and splashed its way through the potholes in the parking lot and out onto the street. After passing the untidy sprawl of a lumberyard, it made a right turn onto a side street and a left onto the highway.

A fried chicken place at the corner was filling the air with the most mouth-watering aroma, reminding Norah that all she’d eaten that day was the hot dog her mother had bought her at Union Station before she’d boarded the one o’clock train.

And that reminded her of their conversation just before she left. “Haven’t you always dreamed of a Christmas like you see in the movies, Norah honey?” Her mother’s blue eyes were moist. “You know, the little houses and streets all trimmed with snow? That’s the way it could be in Pinegrove.”

“Mom, that movie snow is mostly fake! I heard they made it out of soap. And the streets are likely in California someplace. Didn’t you wonder how that ditzy family could all stand around outside in their pajamas, watching the dad string the lights? It was totally fake!”

Now, from the back of the taxi, Norah craned to see what there was of the little town of Pinegrove. “I’m not sure exactly where my aunt lives,” she admitted. “I thought she’d be the one picking me up.”

“Oh, the lady doesn’t live in the village. Her place is a coupla miles out.” The driver was watching her. “Miz Stoppard a relative of yours?”

“My father’s aunt,” Norah replied, peering out through the rain. With the exception of the train station and the lumberyard, the town was just one street deep. Small houses straggled along the highway as far as the “Come Back Soon” sign. There, they petered out altogether, and bare fields and trees took over.

“You here all by yourself?” The cabbie was inquisitive.

“My mom’s coming in a couple of days,” Norah replied. “And my cousins will be here for Christmas.” She saw the eyebrows in the mirror rise.

“That so? Miz Stoppard doesn’t get much company, as a rule. She’s a bit of a recluse, you might say.” He pronounced it as if it were two words.

“My mom thought it would be nice for all of us to be together for Christmas this year.” Norah didn’t bother telling the man that up until a month ago, neither she nor her mother knew that Great-aunt Caroline was even still alive.

“We invited her to come and spend the holidays with us. But when she said she couldn’t, Mom decided we would bring the festivities to her.”

“That so. And what did she say to that?”

Norah traced a drop of condensation as it slid down the window beside her. “She said she had a big house and had never been known to turn anyone away.” Which was not exactly what you could call an invitation. When Norah had pointed that out to her mother, Ginny had only laughed. “It’ll be perfect, Norah. You’ll see. Wonderful fun.” Everything always was, for Ginny. As far as Norah was concerned, nothing was turning out the way it was supposed to.

Ever since Ginny had learned that she and Norah would be leaving Victoria and moving east to Toronto, she had been going on about living closer to her brother Richard and his wife and two children. “For the first time in years, Norah, our family can spend the holidays together,” Ginny had crowed.

When Ginny discovered that her late husband’s aunt was still living in Ontario, she came up with the idea of inviting her too. It didn’t matter that the old lady was no relation to Uncle Richard, Auntie Gwen or the cousins.

Then, at the last minute, still surrounded by packing crates in their new apartment, Ginny had been called back out west. Some urgent problem the person who was taking over was having, and only Ginny could fix it. Now what? Christmas was only a week away.

“It’s really no problem, sweetie,” Ginny promised. “I’ll just call Aunt Caroline and see if you can go on up there ahead of me. And I’ll join you the minute I get back.”

“I’ll go with you, Mom,” Norah decided. “I know I could stay at Ashley’s.”

“No, it’ll be much quicker if I just do what has to be done and fly right back.”

“Let me stay here then,” Norah pleaded. “I could have all the unpacking done by the time you get back.”

Ginny shook her head. “I don’t know a soul in this city I could ask to stay with you, darling. No, this way is best. I’ll get you a ticket for the train. And here’s an idea! Why don’t we call Richard and see if the kids can go on ahead too? You three could be all together for a while.”

“I bet Andrew and Becca are looking forward to this holiday about as much as I am,” grumbled Norah.

When she’d called her brother in Guelph, Ginny had learned that school for the cousins was not yet out for the Christmas break. The only reason Norah was already on holiday was that she would be starting Grade Eight in a new school after the New Year.

“I guess you’ll just have to go on ahead by yourself,” Ginny announced, setting the phone back down on the floor beside the couch where she and Norah were unwrapping dishes. She picked up another package, smiling brightly. “But that’s okay. I’m sure your Great-aunt Caroline will spoil you rotten.”

By this time, the taxi had turned off the highway between two stone pillars and into a lane overhung with dripping trees. A large house of grey stone loomed ahead in the cold rain. The cab pulled up at the front of the house and stopped.

This place was not what Norah had imagined when her mother had promised Christmas in the country. She had pictured a rambling house of white clapboard, a wide, welcoming verandah, coloured lights strung from gingerbread trim, a wreath in every lighted window. And snow, of course.

“Well, this is it,” the cabbie announced, opening the back door of the car.

Norah emerged from the taxi an inch at a time, looking up at the gloomy house, its chimneys wrapped in fog.

There was no verandah, no front porch of any kind, and no lights beckoned from the unfriendly windows. In fact, the place looked deserted. In the trees to the left, Norah spotted a detached garage with old-fashioned, wooden doors.

After depositing the suitcase on the stone step, the driver got back into the cab and splashed away again down the lane, without even waiting to see if anyone answered the door.

Norah had just about decided that no one was home and was half-hoping that they weren’t, when the big front door swung suddenly inward.

“Come inside,” an icy voice commanded. “Don’t just stand there. You’re letting in the rain.”